Nka 29 05 Ongiri V2 Sh Copy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2 Punk – Eine Einleitung

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit „Die Geschichte des Punk und seiner Szenen“ >Band 1 von 1< Verfasser Armin Wilfling angestrebter akademischer Grad Magister der Philosophie (Mag. phil.) Wien, 2009 Studienkennzahl lt. A 316 Studienblatt: Studienrichtung lt. Musikwissenschaft Studienblatt: Betreuerin / Betreuer: Dr. Emil Lubej Die Geschichte des Punk und seiner Szenen, Armin Wilfling Seite 2 1 KURZBESCHREIBUNGEN...................................................................................................................... 7 1.1 DEUTSCHSPRACHIGE ZUSAMMENFASSUNG ........................................................................................... 7 1.2 ENGLISH ABSTRACT .............................................................................................................................. 7 2 PUNK – EINE EINLEITUNG.................................................................................................................... 9 2.1 STILDEFINIERENDE MERKMALE DES PUNKS ......................................................................................... 9 2.2 LESEANLEITUNG ................................................................................................................................. 13 3 PUNK – EINE GESCHICHTE ................................................................................................................ 15 3.1 URSPRÜNGE UND VORLÄUFER ............................................................................................................ 17 3.1.1 Garage Rock................................................................................................................................. -

FREE||| We Got Power!: Hardcore Punk Scenes From

WE GOT POWER!: HARDCORE PUNK SCENES FROM 1980S SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA FREE DOWNLOAD David Markey | 306 pages | 10 Jan 2013 | Bazillion Points | 9781935950073 | English | Brooklyn, United States We Got Power! Hardcore Punk Scenes From 1980s Southern California (David Markey) Their job as reporters covering the scene for the fanzine they started put them in many key places to document the scene from an unique prospective that gets you the straight scoop. Meanwhile, their amazing photographs captured the dilapidated houses, abandoned storefronts, and disaffected youth culture of the early Reagan era. Redd Kross plays Santa Monica Beach. We Got Power proofs. Cancel reply Your email address will not be published. Ian has a great eye, and was crucial to this project. By the time he was ready to release it, though, Ecstatic Peace! I kind of get over it and move on. I think one of the advantages to waiting was the advances made in software for home computers, which is where this project started, with a negative scanner and film We Got Power!: Hardcore Punk Scenes from 1980s Southern California towards the end of Go HERE to see all the latest record reviews. Friedman: they had great shots including all of the darkroom aspects. Essential We Got Power!: Hardcore Punk Scenes from 1980s Southern California Go to Top Back to Shop Search. We Got Power! Inhe accidentally discovered he was adopted, leading to work on the autobiography Dark Circles. One might think that maybe, when TYPB came out that might have been the perfect time to capitalize on your previous work. -

The Punk Vault : Lovedolls Superstar Fully Realized DVD Page 1 of 13

The Punk Vault : Lovedolls Superstar Fully Realized DVD Page 1 of 13 The Punk Vault « Selections from The Punk Vault [Love Canal] Lovedolls Superstar Fully Realized DVD Lovedolls Superstar Fully Realized - DVD Music Video Distributors/We Got Power Films In 1986, punk filmmaker Dave Markey made a sequel to his underground punk classic, Desperate Teenage Lovedolls with a much larger budget and titled it Lovedolls Superstar. It was a much longer film with a much better story and featured nearly all the characters of the first film, who were played by friends from the local punk rock scene. Much like the first film, it saw a very limited release obviously (what do you expect with a budget of 2000 dollars), and I never even got to see it until this DVD was released! Now 20 years later, it finally makes its way to DVD and easy accessibility, but instead of the original version, we get the “fully realized” version or directors cut if you will. Many scenes were added, some were removed, it was cleaned up, and it ends up being shorter than the original cut! Not being able to compare to the original, I can’t tell you if the film suffered for it, but I seriously doubt that it did. The http://www.punkvinyl.com/2006/04/05/lovedolls-superstar-fully-realized-dvd/ 4/6/2006 The Punk Vault : Lovedolls Superstar Fully Realized DVD Page 2 of 13 soundtrack was left nearly intact with the exception of the omission of anything Greg Ginn had contributed, because for some reason he wanted no part of it anymore and actually filed suit to have his stuff removed from the movies (this happened on the first film and DVDs that were ready to ship had to be destroyed). -

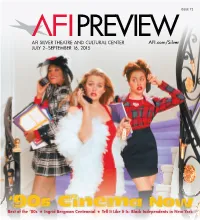

AFI PREVIEW Is Published by the Age 46

ISSUE 72 AFI SILVER THEATRE AND CULTURAL CENTER AFI.com/Silver JULY 2–SEPTEMBER 16, 2015 ‘90s Cinema Now Best of the ‘80s Ingrid Bergman Centennial Tell It Like It Is: Black Independents in New York Tell It Like It Is: Contents Black Independents in New York, 1968–1986 Tell It Like It Is: Black Independents in New York, 1968–1986 ........................2 July 4–September 5 Keepin’ It Real: ‘90s Cinema Now ............4 In early 1968, William Greaves began shooting in Central Park, and the resulting film, SYMBIOPSYCHOTAXIPLASM: TAKE ONE, came to be considered one of the major works of American independent cinema. Later that year, following Ingrid Bergman Centennial .......................9 a staff strike, WNET’s newly created program BLACK JOURNAL (with Greaves as executive producer) was established “under black editorial control,” becoming the first nationally syndicated newsmagazine of its kind, and home base for a Best of Totally Awesome: new generation of filmmakers redefining documentary. 1968 also marked the production of the first Hollywood studio film Great Films of the 1980s .....................13 directed by an African American, Gordon Park’s THE LEARNING TREE. Shortly thereafter, actor/playwright/screenwriter/ novelist Bill Gunn directed the studio-backed STOP, which remains unreleased by Warner Bros. to this day. Gunn, rejected Bugs Bunny 75th Anniversary ...............14 by the industry that had courted him, then directed the independent classic GANJA AND HESS, ushering in a new type of horror film — which Ishmael Reed called “what might be the country’s most intellectual and sophisticated horror films.” Calendar ............................................15 This survey is comprised of key films produced between 1968 and 1986, when Spike Lee’s first feature, the independently Special Engagements ............12-14, 16 produced SHE’S GOTTA HAVE IT, was released theatrically — and followed by a new era of studio filmmaking by black directors. -

Sonic Youth: Celebrity DIY

Essays — Peer Reviewed ZoneModa Journal. Vol. 7 (2017) https://doi.org/10.6092/issn.2611-0563/7585 ISSN 2611-0563 Sonic Youth: celebrity DIY Alice Militello Pubblicato: 29 dicembre 2017 Abstract In New York City’s early ’80s music scene and beyond, the band Sonic Youth represents a special case of the celebrity’s concept. It cannot be reduced to the record sales or scandals, like other famous people. They don’t have the typical self-destructive streak of the stars of the show business, which is the basis of the fortune and, at the same time, the defeat of other musicians. They don’t even have the cult of personality, which has destabilized other crews of the time. However Sonic Youth, during their three decades of career, have been able to find a space in the music scene, to involve a broad segment of audience and lovers; becoming a kind of model for younger generations of musicians. Furthermore, the members of Sonic Youthcan be considered such as influencers ahead of his time, thanks to their ability to find new talents. The present study aims to analyze the concept of celebrity applied to the Sonic Youth language, from 1981 (starting year) to 1994, the year of Experimental Jet Set, Trash No Star album, which brings the group to that DIY (Do-It-Yourself) punk ethics that denotes them from the beginning; to plot the New York’s environment in which they fit; and how the entry into the mainstream world changes the aesthetics of the group. In other words, the research is a breakthrough of the band’s long career, marking the highlights that made them the Sonic Youth. -

Punk Lyrics and Their Cultural and Ideological Background: a Literary Analysis

Punk Lyrics and their Cultural and Ideological Background: A Literary Analysis Diplomarbeit zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Magisters der Philosophie an der Karl-Franzens Universität Graz vorgelegt von Gerfried AMBROSCH am Institut für Anglistik Begutachter: A.o. Univ.-Prof. Mag. Dr. Hugo Keiper Graz, 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE 3 INTRODUCTION – What Is Punk? 5 1. ANARCHY IN THE UK 14 2. AMERICAN HARDCORE 26 2.1. STRAIGHT EDGE 44 2.2. THE NINETEEN-NINETIES AND EARLY TWOTHOUSANDS 46 3. THE IDEOLOGY OF PUNK 52 3.1. ANARCHY 53 3.2. THE DIY ETHIC 56 3.3. ANIMAL RIGHTS AND ECOLOGICAL CONCERNS 59 3.4. GENDER AND SEXUALITY 62 3.5. PUNKS AND SKINHEADS 65 4. ANALYSIS OF LYRICS 68 4.1. “PUNK IS DEAD” 70 4.2. “NO GODS, NO MASTERS” 75 4.3. “ARE THESE OUR LIVES?” 77 4.4. “NAME AND ADDRESS WITHHELD”/“SUPERBOWL PATRIOT XXXVI (ENTER THE MENDICANT)” 82 EPILOGUE 89 APPENDIX – Alphabetical Collection of Song Lyrics Mentioned or Cited 90 BIBLIOGRAPHY 117 2 PREFACE Being a punk musician and lyricist myself, I have been following the development of punk rock for a good 15 years now. You might say that punk has played a pivotal role in my life. Needless to say, I have also seen a great deal of media misrepresentation over the years. I completely agree with Craig O’Hara’s perception when he states in his fine introduction to American punk rock, self-explanatorily entitled The Philosophy of Punk: More than Noise, that “Punk has been characterized as a self-destructive, violence oriented fad [...] which had no real significance.” (1999: 43.) He quotes Larry Zbach of Maximum RockNRoll, one of the better known international punk fanzines1, who speaks of “repeated media distortion” which has lead to a situation wherein “more and more people adopt the appearance of Punk [but] have less and less of an idea of its content. -

Boo-Hooray Catalog #8: Music Boo-Hooray Catalog #8

Boo-Hooray Catalog #8: Music Boo-Hooray Catalog #8 Music Boo-Hooray is proud to present our eighth antiquarian catalog, dedicated to music artifacts and ephemera. Included in the catalog is unique artwork by Tomata Du Plenty of The Screamers, several incredible items documenting music fan culture including handmade sleeves for jazz 45s, and rare paste-ups from reggae’s entrance into North America. Readers will also find the handmade press kit for the early Björk band, KUKL, several incredible hip-hop posters, and much more. For over a decade, we have been committed to the organization, stabilization, and preservation of cultural narratives through archival placement. Today, we continue and expand our mission through the sale of individual items and smaller collections. We encourage visitors to browse our extensive inventory of rare books, ephemera, archives and collections and look forward to inviting you back to our gallery in Manhattan’s Chinatown. Catalog prepared by Evan Neuhausen, Archivist & Rare Book Cataloger and Daylon Orr, Executive Director & Rare Book Specialist; with Beth Rudig, Director of Archives. Photography by Ben Papaleo, Evan, and Daylon. Layout by Evan. Please direct all inquiries to Daylon ([email protected]). Terms: Usual. Not onerous. All items subject to prior sale. Payment may be made via check, credit card, wire transfer or PayPal. Institutions may be billed accordingly. Shipping is additional and will be billed at cost. Returns will be accepted for any reason within a week of receipt. Please provide advance notice of the return. Table of Contents 31. [Patti Smith] Hey Joe (Version) b/w Piss Factory .................. -

28Th Leeds International Film Festival Presents Leeds Free Cinema Week Experience Cinema in New Ways for Free at Liff 28 from 7 - 13 November

LIFF28th 28 Leeds International Film Festival CONGRATULATIONS TO THE LEEDS INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL IN YOUR 28TH YEAR The BFI is proud to partner with Screen Yorkshire in a fantastic year for filmmaking in the region INCLUDING ‘71 GET SANTA SCREENING AT LIFF28 X + Y CATCH ME DADDY & LIFF28 OPENING NIGHT FILM TESTAMENT OF YOUTH Image: (2014) Testament of Youth James Kent Dir. bfi.org.uk/FilmFund Film Fund Ad LIFF 210x260 2014-10_FINAL 3.indd 1 27/10/2014 11:06 WELCOME From its beginnings at the wonderful, century-old Hyde Park Leeds International Film Festival is a celebration of both Picture House to its status now as a major national film event, film culture and Leeds itself, with this year more than 250 CONGRATULATIONS Leeds International Film Festival has always aimed to bring screenings, events and exhibitions hosted in 16 unique a unique and outstanding selection of global film culture locations across the city. Our venues for LIFF28 include the TO THE LEEDS INTERNATIONAL to the city for everyone to experience. This achievement main hub of Leeds Town Hall, the historic cinemas Hyde is not possible without collaborations and this year we’ve Park Picture House and Cottage Road, other city landmarks FILM FESTIVAL IN YOUR 28TH YEAR assembled our largest ever line-up of partners. From our like City Varieties, The Tetley, Left Bank, and Royal Armouries, long-term major funders the European Union and the British Vue Cinemas at The Light and the Everyman Leeds, in their Film Institute to exciting new additions among our supporting recently-completed Screen 4, and Chapel FM, the new arts The BFI is proud to partner with Screen Yorkshire organisations, including Game Republic, Infiniti, and Trinity centre for East Leeds. -

The History of American Punk Rock 1980 – 1986

THE HISTORY OF AMERICAN PUNK ROCK 1980 – 1986 A documentary film by Paul Rachman Inspired by the book American Hardcore: A Tribal History by Steven Blush A SONY PICTURES CLASSICS RELEASE East Coast Publicity: West Coast Publicity: Distributor: Falo Ink. Block Korenbrot Sony Pictures Classics Shannon Treusch Melody Korenbrot Carmelo Pirrone Betsy Rudnick Lisa Danna Angela Gresham 850 7th Ave, Suite 1005 110 S. Fairfax Ave, #310 550 Madison Ave New York, NY 10019 Los Angeles, CA 90036 New York, NY 10022 212-445-7100 tel 323-634-7001 tel 212-833-8833 tel 212-445-0623 fax 323-634-7030 fax 212-833-8844 fax Visit the Sony Pictures Classics Internet site at: http:/www.sonyclassics.com SYNOPSIS Generally unheralded at the time, the early 1980s hardcore punk rock scene gave birth to much of the rock music and culture that followed. There would be no Nirvana, Beastie Boys or Red Hot Chili Peppers were it not for hardcore pioneers such as Black Flag, Bad Brains and Minor Threat. Hardcore was more than music—it was a social movement created by Reagan-era misfit kids. The participants constituted a tribe unto themselves—some finding a voice, others an escape in the hard-edged music. And while some sought a better world, others were just angry and wanted to raise hell. AMERICAN HARDCORE traces this lost subculture, from its early roots in 1980 to its extinction in 1986. Page 2 ABOUT THE PRODUCTION Paul Rachman and Steven Blush met through the hardcore punk rock scene in the early 1980s. Steven promoted shows in Washington, DC, and Paul directed the first music videos for bands like Bad Brains and Gang Green. -

Page 1 of 6 Off the Press, up to Date: Cut Shorts

Off the Press, Up to Date: Cut Shorts - Short Films of Dave Markey 1974 - 2004 Page 1 of 6 BlogThis! Download Full DVD Movies All News, All The Time We compare movie downloading sites free. Millions of DVD movies & TV! Ads by Goooooogle May 11, 2006 Cut Shorts - Short Films of Dave Markey 1974 - 2004 Oaks, PA- Eclectic DVD and We Got Power Films are pleased to announce the home viewing release of Cut Shorts: Short Films of Dave Markey 1974 - 2004 for worldwide distribution on DVD. "Masks. More than anything else, these films are about masks. Cheap, hideous, gaudy, disposable Halloween Masks. Creepy clown masks, awful Adolf Hitler masks, frightening beyond belief Easter Bunny masks found in dime stores in the 1970’s." Says David Markey. But more about masks later. This collection documents 30 years in the life and work of Previous Posts http://off-the-press-up-to-date.blogspot.com/2006/05/cut-shorts-short-films-of-dave-marke... 5/11/2006 Off the Press, Up to Date: Cut Shorts - Short Films of Dave Markey 1974 - 2004 Page 2 of 6 Versus The Mirror goes HOME. independent filmmaker David Markey. The details of Markey’s life are all HOTWAX COSMETICS Presents HOT FRID here; his childhood friends, the apartment buildings and alleyways where he At San Jose's STUDIO 8 May 12th, 2006 grew up and which he eventually turned into his own movie studio, STAUBGOLD/QUECKSILBER MAY NEWS complete with a stable of “actors,” real-life props and street-bound extras. Blueprint Recordings - May Update Estonian Pop Queen Éha Brings Somethi Much of Markey’s work may seem surreal, but actually it's “all-too-real.” His Different to the Red Lion! frenetic documentary style mixes with Punk Fiction on the dime (literally). -

One Mag Two Covers WHAT’S HOT

1 One mag two Covers WHAT’S HOT View From The Coffin Ghost Linda Åkerberg Editor In Chief/Founder - Andrea Rigano Art Director - Alexandra Romano [email protected] Advertising - Silvia Rapisarda [email protected] Traduzioni - Chiara Zetti Photographers Luca Benedet, Verena Stefanie Grotto, Kreator, Alex Luise, Alan Maag, Mike Pireddu, Stefano “Tave” Righi, StreetBoxVideoLab, Federico Tognoli, Giuseppe Toninelli Contributors Milo Bandini, Marco Capelli, Mat The Cat, Stefano Campagnolo, Matteo Cavanna, Cristiano Crepaldi, Paola Dal Bosco, Fabrizio De Guidi, SECSE, Flavio MILAN Ignelzi, Andrea KNGL Longo, Cecilia Marin, Max Mbassadò, Angelo Mora(donas), Alexandra Oberhofer, Eros Pasi, Alessandro Scontrino, Trapdoor, Alex ‘Wizo’, Marco ‘X-Man’ Xodo Marianna Hardcore PHOTO: | Rigablood Stampa Tipografia Nuova Jolly - Viale Industria 28 35030 Rubano (PD) Salad Days Magazine è una rivista registrata presso il 8 Library 50 Touché Amoré Tribunale di Vicenza, N. 1221 del 04/03/2010. 10 Paper Toy 54 Fishbone 12 Noem 507 58 Grand Master Flash Get in touch www.saladdaysmag.com 18 Don’t Sweat the Technique 60 Warriors [email protected] 22 Ghost 68 Family Album facebook.com/saladdaysmag 24 View From the Coffin 76 Chris Dodge twitter.com/SaladDays_it 29 El Jefe design 80 DTS Instagram - @saladdaysmagazine 34 ROBBIE MADDISON | TUCSON, AZ NYC History - The Tattoo Ban 83 ...And You Will Know Us By The Trail of Dead L’editore è a disposizione di tutti gli interessati nel 38 John Cardiel 86 Indigesti Vs La Crisi collaborarecon testi immagini. Tutti i contenuti di que- 40 Tommy Guerrero 88 Torae CALIFORNIA SPORTS SEE ROBBIE MADDISON IN sta pubblicazione sono soggetti a copyright, é vietata 42 Italians goes Tirol - Pinocchietto Tour 90 Highlights la riproduzione anche parziale di testi, documenti e TEL: 011-927-7943 46 Grime Vs New York New York 94 Saints & Sinners WWW.CALIFORNIASPORT.INFO foto senza l’autorizzazione dell’editore. -

Ein Leben Aus Musik

Kieler Beiträge zur Filmmusikforschung 05.2// August 201o Topic: Rockumentaries Kieler Beiträge zur Filmmusikforschung, 5.2, 2010 // 169 Kieler Beiträge zur Filmmusikforschung, 5.2, 2010 // 170 Kieler Beiträge zur Filmmusikforschung, 5.2, 2010 // 171 Impressum Copyright by Kieler Gesellschaft für Filmmusikforschung, Kiel 2010 Copyright (für die einzelnen Artikel) by den Autoren, 2010 ISSN 1866-4768 Verantwortliche Redakteure: Susan Levermann, Patrick Niemeier, Willem Strank Kieler Beiträge zur Filmmusikforschung ISSN 1866-4768 Herausgeber: Niemeier, Patrick (Kiel) Strank M.A., Willem (Kiel) Wulff, Prof. Dr. Hans Jürgen (Westerkappeln/Kiel) Redaktion: Kerstin Bittner (Kiel) Janwillem Dubil (Kiel) Julia Fendler (Kiel) Knut Heisler (Kiel) Jan Kästel (Kiel) Frederike Kiesel (Kiel) Patrick Kraft (Kiel) Susan Levermann (Kiel) Imke Schröder (Kiel) Editorial Board: Claudia Bullerjahn (Gießen) Christoph Henzel (Würzburg) Linda Maria Koldau (Frankfurt) Georg Maas (Halle) Siegfried Oechsle (Kiel) Albrecht Riethmüller (Berlin) Fred Ritzel (Oldenburg) Hans Christian Schmidt-Banse (Osnabrück) Bernd Sponheuer (Kiel) Jürg Stenzl (Salzburg) Wolfgang Thiel (Potsdam) Hans J. Wulff (Kiel) Kontakt: [email protected] Kieler Gesellschaft für Filmmusikforschung c/o Hans J. Wulff Institut für NDL- und Medienwissenschaft Leibnizstraße 8 D-24118 Kiel Kieler Beiträge zur Filmmusikforschung, 5.2, 2010 // 172 Inhaltsverzeichnis Impressum..........................................................................................................................171