Charlotte Smith’S Own Death

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Entre Classicismo E Romantismo. Ensaios De Cultura E Literatura

Entre Classicismo e Romantismo. Ensaios de Cultura e Literatura Organização Jorge Bastos da Silva Maria Zulmira Castanheira Studies in Classicism and Romanticism 2 FLUP | CETAPS, 2013 Studies in Classicism and Romanticism 2 Studies in Classicism and Romanticism is an academic series published on- line by the Centre for English, Translation and Anglo-Portuguese Studies (CETAPS) and hosted by the central library of the Faculdade de Letras da Universidade do Porto, Portugal. Studies in Classicism and Romanticism has come into being as a result of the commitment of a group of scholars who are especially interested in English literature and culture from the mid-seventeenth to the mid- nineteenth century. The principal objective of the series is the publication in electronic format of monographs and collections of essays, either in English or in Portuguese, with no pre-established methodological framework, as well as the publication of relevant primary texts from the period c. 1650–c. 1850. Series Editors Jorge Bastos da Silva Maria Zulmira Castanheira Entre Classicismo e Romantismo. Ensaios de Cultura e Literatura Organização Jorge Bastos da Silva Maria Zulmira Castanheira Studies in Classicism and Romanticism 2 FLUP | CETAPS, 2013 Editorial 2 Sumário Apresentação 4 Maria Luísa Malato Borralho, “Metamorfoses do Soneto: Do «Classicismo» ao «Romantismo»” 5 Adelaide Meira Serras, “Science as the Enlightened Route to Paradise?” 29 Paula Rama-da-Silva, “Hogarth and the Role of Engraving in Eighteenth-Century London” 41 Patrícia Rodrigues, “The Importance of Study for Women and by Women: Hannah More’s Defence of Female Education as the Path to their Patriotic Contribution” 56 Maria Leonor Machado de Sousa, “Sugestões Portuguesas no Romantismo Inglês” 65 Maria Zulmira Castanheira, “O Papel Mediador da Imprensa Periódica na Divulgação da Cultura Britânica em Portugal ao Tempo do Romantismo (1836-1865): Matérias e Imagens” 76 João Paulo Ascenso P. -

British Poetry of the Long Nineteenth Century

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Zea E-Books Zea E-Books 12-1-2019 British Poetry of the Long Nineteenth Century Beverley Rilett University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/zeabook Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Rilett, Beverley, "British Poetry of the Long Nineteenth Century" (2019). Zea E-Books. 81. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/zeabook/81 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Zea E-Books at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Zea E-Books by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. British Poetry of the Long Nineteenth Century A Selection for College Students Edited by Beverley Park Rilett, PhD. CHARLOTTE SMITH WILLIAM BLAKE WILLIAM WORDSWORTH SAMUEL TAYLOR COLERIDGE GEORGE GORDON BYRON PERCY BYSSHE SHELLEY JOHN KEATS ELIZABETH BARRETT BROWNING ALFRED TENNYSON ROBERT BROWNING EMILY BRONTË GEORGE ELIOT MATTHEW ARNOLD GEORGE MEREDITH DANTE GABRIEL ROSSETTI CHRISTINA ROSSETTI OSCAR WILDE MARY ELIZABETH COLERIDGE ZEA BOOKS LINCOLN, NEBRASKA ISBN 978-1-60962-163-6 DOI 10.32873/UNL.DC.ZEA.1096 British Poetry of the Long Nineteenth Century A Selection for College Students Edited by Beverley Park Rilett, PhD. University of Nebraska —Lincoln Zea Books Lincoln, Nebraska Collection, notes, preface, and biographical sketches copyright © 2017 by Beverly Park Rilett. All poetry and images reproduced in this volume are in the public domain. ISBN: 978-1-60962-163-6 doi 10.32873/unl.dc.zea.1096 Cover image: The Lady of Shalott by John William Waterhouse, 1888 Zea Books are published by the University of Nebraska–Lincoln Libraries. -

Praise, Patronage, and the Penshurst Poems: from Jonson (1616) to Southey (1799)

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2015-09-24 Praise, Patronage, and the Penshurst Poems: From Jonson (1616) to Southey (1799) Gray, Moorea Gray, M. (2015). Praise, Patronage, and the Penshurst Poems: From Jonson (1616) to Southey (1799) (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/27395 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/2486 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Praise, Patronage, and the Penshurst Poems: From Jonson (1616) to Southey (1799) by Mooréa Gray A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS GRADUATE PROGRAM IN ENGLISH CALGARY, ALBERTA SePtember, 2015 © Mooréa Gray 2015 Abstract The Penshurst grouP of Poems (1616-1799) is a collection of twelve Poems— beginning with Ben Jonson’s country-house Poem “To Penshurst”—which praises the ancient estate of Penshurst and the eminent Sidney family. Although praise is a constant theme, only the first five Poems Praise the resPective Patron and lord of Penshurst, while the remaining Poems Praise the exemplary Sidneys of bygone days, including Sir Philip and Dorothy (Sacharissa) Sidney. This shift in praise coincides with and is largely due to the gradual shift in literary economy: from the Patronage system to the literary marketPlace. -

Charlotte Smith, William Cowper, and William Blake: Some New Documents

ARTICLE Charlotte Smith, William Cowper, and William Blake: Some New Documents James King Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly, Volume 13, Issue 2, Fall 1979, pp. 100-101 100 CHARLOTTE SMITH, WILLIAM COWPER, AND WILLIAM BLAKE: SOME NEW DOCUMENTS JAMES KING lthough her reputation is somewhat diminished Rose, of 25 April 1806 (Huntington)." As before, now, Charlotte Smith was the most celebrated Mrs. Smith is complaining about Hayley's neglect of A novelist in England in the early 1790s. Like her. George Romney, John Flaxman, William Cowper, and William Blake, Mrs. Smith was one of a number of I lose a great part of the regret I might writers and painters assisted by William Hayley in otherwise feel in recollecting, that a various ways. Mrs. Smith met Cowper at Eartham in mind so indiscriminating, who is now 1792, and the events of that friendship have been seized with a rage for a crooked figure= chronicled.1 Mrs. Smith never met William Blake, and maker & now for an engraver of Ballad only one excerpt from a letter linking them has pictures (the young Mans tragedy; & the previously been published. In this note, I should jolly Sailers Farewell to his true love Sally) —I dont mean the Hayleyan like to provide some additional information on Mrs. 5 Smith and Cowper, but I shall as well cite three collection of pretty ballads) —Such a unpublished excerpts from her correspondence in mind, can never be really attached; or which she comments on Blake. is the attachment it can feel worth having — In an article of 1952, Alan Dugald McKillop provided a n excellent account of Charlotte Smith's The "crooked figure=maker" is probably a reference letters.2 In the course of that essay, McKilloD to Flaxman and his hunch-back; despite the notes a facetiou s and denigrating remark of 20 March disclaimer, the engraver is more than likely to be 1806 (Hunt ington) about Hayley's Designs to a Series Blake. -

William Blake 1 William Blake

William Blake 1 William Blake William Blake William Blake in a portrait by Thomas Phillips (1807) Born 28 November 1757 London, England Died 12 August 1827 (aged 69) London, England Occupation Poet, painter, printmaker Genres Visionary, poetry Literary Romanticism movement Notable work(s) Songs of Innocence and of Experience, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, The Four Zoas, Jerusalem, Milton a Poem, And did those feet in ancient time Spouse(s) Catherine Blake (1782–1827) Signature William Blake (28 November 1757 – 12 August 1827) was an English poet, painter, and printmaker. Largely unrecognised during his lifetime, Blake is now considered a seminal figure in the history of the poetry and visual arts of the Romantic Age. His prophetic poetry has been said to form "what is in proportion to its merits the least read body of poetry in the English language".[1] His visual artistry led one contemporary art critic to proclaim him "far and away the greatest artist Britain has ever produced".[2] In 2002, Blake was placed at number 38 in the BBC's poll of the 100 Greatest Britons.[3] Although he lived in London his entire life except for three years spent in Felpham[4] he produced a diverse and symbolically rich corpus, which embraced the imagination as "the body of God",[5] or "Human existence itself".[6] Considered mad by contemporaries for his idiosyncratic views, Blake is held in high regard by later critics for his expressiveness and creativity, and for the philosophical and mystical undercurrents within his work. His paintings William Blake 2 and poetry have been characterised as part of the Romantic movement and "Pre-Romantic",[7] for its large appearance in the 18th century. -

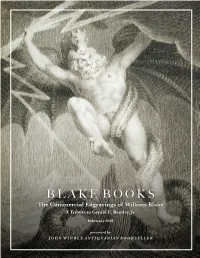

Blake Books, Contributed Immeasurably to the Understanding and Appreciation of the Enormous Range of Blake’S Works

B L A K E B O O K S The Commercial Engravings of William Blake A Tribute to Gerald E. Bentley, Jr. February 2018 presented by J O H N W I N D L E A N T I Q U A R I A N B O O K S E L L E R T H E W I L L I A M B L A K E G A L L E R Y B L A K E B O O K S The Commercial Engravings of William Blake A Tribute to Gerald E. Bentley, Jr. February 2018 Blake is best known today for his independent vision and experimental methods, yet he made his living as a commercial illustrator. This exhibition shines a light on those commissioned illustrations and the surprising range of books in which they appeared. In them we see his extraordinary versatility as an artist but also flashes of his visionary self—flashes not always appreciated by his publishers. On display are the books themselves, objects that are far less familiar to his admirers today, but that have much to say about Blake the artist. The exhibition is a small tribute to Gerald E. Bentley, Jr. (1930 – 2017), whose scholarship, including the monumental bibliography, Blake Books, contributed immeasurably to the understanding and appreciation of the enormous range of Blake’s works. J O H N W I N D L E A N T I Q U A R I A N B O O K S E L L E R 49 Geary Street, Suite 205, San Francisco, CA 94108 www.williamblakegallery.com www.johnwindle.com 415-986-5826 - 2 - B L A K E B O O K S : C O M M E R C I A L I L L U S T R A T I O N Allen, Charles. -

Women Poets in Romanticism

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by International Burch University 1st International Conference on Foreign Language Teaching and Applied Linguistics May 5-7 2011 Sarajevo Women Poets in Romanticism Alma Ţero English Department, Faculty of Philosophy University of Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina [email protected] Abstract: In Bosnia, modern university literary courses usually do not even include Romantic women poets into their syllabuses, which is a huge shortcoming for every student interested in gender studies as such. That is why this paper focuses on the Romantic Era 1790s-1840s and those women who had broken out of their prisons and into the literary world of poetry. Many events, such as the French Revolution, political and social turbulences in Britain, rising female reading audiences, and public coteries have influenced the scope of women poets‘ development and reach. Due to great tensions, male and female Romantic poetry progressed in two contrary currents with opposite ideas regarding many a problem and issue. However, almost every Romantic artist at that time produced works of approval regarding social reforms. Women continued writing, which gained them greater acknowledgment and economic success after all. Poets such as Charlotte Smith and Anna Barbauld were true Romantic representatives of female poets and this is why we shall mostly focus on specific display of their poetic works, language, and lives. Key Words: Romantic poetry, Women poets, Charlotte Smith, Anna Barbauld Introduction The canon of British Romantic writing has traditionally been focused on the main male representatives of the era, which highly contributed to the distortion of our understanding of its literary culture. -

William Cowper and George Romney: Public and Private Men Joan Addison

William Cowper and George Romney: Public and Private Men Joan Addison It was at Eartham, William Hayley’s Sussex home, in August 1792, that William Cowper met the artist George Romney. In the previous May, Hayley, benefactor of artists and admirer of Cowper, had made his first visit to the poet at Weston. During his visit, he had written to his old friend Romney, suggesting such a meeting. His intention, he wrote in his Life of George Romney, was ‘to enliven [him] with a prospect of sharing with me the intellectual banquet of Cowper’s conversation by meeting him at Eartham’. When the meeting did take place, Hayley’s prediction that the two men would enjoy each other’s company proved correct. ‘Equally quick, and tender, in their feelings’, Hayley wrote, ‘they were peculiarly formed to relish the different but congenial talents, that rendered each an object of affectionate admiration’1. The pleasure that the poet and the painter shared in each other’s company was to result in the production of two notable creations, the portrait Romney made of Cowper during the visit to Eartham, and Cowper’s subsequent sonnet, written to Romney in appreciation of his work. ‘Romney,’ Hayley wrote, was ‘eager to execute a portrait of a person so remarkable’, and worked quickly in crayons to produce it.2 An intimate study of Cowper in informal garb, it is now in the National Portrait Gallery. The portrait, twenty-two and a half by eighteen inches, shows the upper part of Cowper’s body, against a brown background. -

Charlotte Smith's Life Writing Among the Dead

THE EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF LIFE WRITING VOLUME IX (2020) LW&D56–LW&D80 Un-earthing the Eighteenth-Century Churchyard: Charlotte Smith’s Life Writing Among the Dead James Metcalf King’s College London ABSTRACT The work of poet and novelist Charlotte Smith (1749–1806) has been consis- tently associated with life writing through the successive revelations of her autobiographical paratexts. While the life of the author is therefore familiar, Smith’s contribution to the relationship between life writing and death has been less examined. Several of her novels and poems demonstrate an awareness of and departure from the tropes of mid-eighteenth-century ‘graveyard poetry’. Central among these is the churchyard, and through this landscape Smith re- vises the literary community of the ‘graveyard school’ but also its conventional life writing of the dead. Reversing the recuperation of the dead through reli- gious, familial, or other compensations common to elegies, epitaphs, funeral sermons, and ‘graveyard poetry’, Smith unearths merely decaying corpses; in doing so she re-writes the life of the dead and re-imagines the life of living com- munities that have been divested of the humic foundations the idealised, famil- iar, localised dead provide. Situated in the context of churchyard literature and the churchyard’s long history of transmortal relationships, this article argues that Smith’s sonnet ‘Written in the Church-Yard at Middleton in Sussex’ (1789) intervenes in the reclamation of the dead through life writing to interrogate what happens when these consolatory processes are eroded. Keywords: Charlotte Smith, graveyard poetry, churchyard, death European Journal of Life Writing, Vol IX, 56–80 2020. -

The Circulation of Émigré Novels During the French Revolution

University of Warwick institutional repository: http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap This paper is made available online in accordance with publisher policies. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item and our policy information available from the repository home page for further information. To see the final version of this paper please visit the publisher’s website. Access to the published version may require a subscription. Author(s): Katherine Astbury Article Title: The Trans-National Dimensions of the Émigré Novel during the French Revolution Year of publication: 2011 Link to published article: http://www.synergiescanada.org/journals/utp/120884/m3462l212630/6 638764534gx2r1p Publisher statement: None The trans-national dimensions of the émigré novel during the French Revolution The French Revolution exerted a curiously harmonising effect on novelistic production as writers across Europe, especially in those countries immediately bordering France, found inspiration in its events and social ramifications. In particular, the dispersal of émigrés across the continent provided writers with a common series of plot devices through which to explore notions of identity and the interplay of politics and sensibility. Émigrés themselves such as Sénac de Meilhan and Mme Souza wrote novels about emigration, drawing on their personal experiences, but English, German and Swiss writers who witnessed emigration also used it as a device to structure their novels. Despite the fact that these texts by their nature deal with the crossing of national frontiers and the fact that they were often translated and circulated across cultures, the study of the émigré novel as a genre has, until now, largely been conducted along national lines with the result that the trans-national nature of the development of the genre has not been recognised. -

William Blake Henry Fuseli Auckland City Art Gallery

WILLIAM BLAKE ILLUSTRATIONS OF THE BOOK OF JOB HENRY FUSELI THE THREE WITCHES OF MACBETH AND ASSOCIATED WORKS AUCKLAND CITY ART GALLERY AUGUST 8 - OCTOBER 2 1980 WILLIAM BLAKE (1757-1827) As poet, watercolourist and engraver, Blake was the creator of an idiosyncratic mythology. Born of a lower middle class merchant family, Blake had no academic training, but attended Henry Par's preparatory drawing school from 1767 until his apprenticeship in 1772 to James Basire, engraver to the Society of Antiquaries. At Westminster Abbey,Blake made drawings for Gough's Sepulchral Monuments in Great Britain (1786), thereby immersing himself in the mediaeval tradition, with which he found a spiritual affinity. In 1782 Blake married and moved to Leicester Fields in London, where he completed and published in 1783 his first work, Poetical Sketches. In these early years he developed lasting friendships with the painters Barry, Fuseli and Flaxman, and for a while shared Flaxman's preoccupation with classical art. For his next major publication, Songs of Innocence, completed in 1789, Blake invented a new engraving technique whereby lyrics and linear design could be reproduced simultaneously in several stages in the copper plate. The resulting prints were then hand-coloured. This complete fusion of tint and illustration recalls mediaeval illuminated manuscripts, from which Blake derived obvious inspiration. From 1790 until 1800 Blake lived in Lambeth and produced books, thematically characterised by energetic protest against eighteenth century morality (The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, 1790-3) and against political authority (Ammca 1793, and The French Revolution, 1791). These works corroborate Blake's radicalism, which was demonstrated by his sympathy with Swedenborg in religion, with Mary Wollstonecaft in education, and with the Jacobins during the French Revolution. -

White Creole Women in the British West Indies

WHITE CREOLE WOMEN IN THE BRITISH WEST INDIES: FROM STEREOTYPE TO CARICATURE Chloe Aubra Northrop, B.S. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS December 2010 APPROVED: Marilyn Morris, Major Professor Laura I. Stern, Committee Member Denise Amy Baxter, Committee Member Richard B. McCaslin, Chair of the Department of History James D. Meernik, Acting Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Northrop, Chloe Aubra. White Creole Women in the British West Indies: From Stereotype to Caricature. Master of Arts (History), December 2010, 107 pp., 2 illustrations, references, 91 titles. Many researchers of gender studies and colonial history ignore the lives of European women in the British West Indies. The scarcity of written information combined with preconceived notions about the character of the women inhabiting the islands make this the “final frontier” in colonial studies on women. Over the long eighteenth century, travel literature by men reduced creole white women to a stereotype that endured in literature and visual representations. The writings of female authors, who also visited the plantation islands, display their opinions on the creole white women through their letters, diaries and journals. Male authors were preoccupied with the sexual morality of the women, whereas the female authors focus on the temperate lifestyles of the local females. The popular perceptions of the creole white women seen in periodicals, literature, and caricatures in Britain seem to follow this trend, taking for their sources the travel histories. Copyright 2010 by Chloe Aubra Northrop ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my wonderful committee, Dr.