William Cowper and George Romney: Public and Private Men Joan Addison

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Entre Classicismo E Romantismo. Ensaios De Cultura E Literatura

Entre Classicismo e Romantismo. Ensaios de Cultura e Literatura Organização Jorge Bastos da Silva Maria Zulmira Castanheira Studies in Classicism and Romanticism 2 FLUP | CETAPS, 2013 Studies in Classicism and Romanticism 2 Studies in Classicism and Romanticism is an academic series published on- line by the Centre for English, Translation and Anglo-Portuguese Studies (CETAPS) and hosted by the central library of the Faculdade de Letras da Universidade do Porto, Portugal. Studies in Classicism and Romanticism has come into being as a result of the commitment of a group of scholars who are especially interested in English literature and culture from the mid-seventeenth to the mid- nineteenth century. The principal objective of the series is the publication in electronic format of monographs and collections of essays, either in English or in Portuguese, with no pre-established methodological framework, as well as the publication of relevant primary texts from the period c. 1650–c. 1850. Series Editors Jorge Bastos da Silva Maria Zulmira Castanheira Entre Classicismo e Romantismo. Ensaios de Cultura e Literatura Organização Jorge Bastos da Silva Maria Zulmira Castanheira Studies in Classicism and Romanticism 2 FLUP | CETAPS, 2013 Editorial 2 Sumário Apresentação 4 Maria Luísa Malato Borralho, “Metamorfoses do Soneto: Do «Classicismo» ao «Romantismo»” 5 Adelaide Meira Serras, “Science as the Enlightened Route to Paradise?” 29 Paula Rama-da-Silva, “Hogarth and the Role of Engraving in Eighteenth-Century London” 41 Patrícia Rodrigues, “The Importance of Study for Women and by Women: Hannah More’s Defence of Female Education as the Path to their Patriotic Contribution” 56 Maria Leonor Machado de Sousa, “Sugestões Portuguesas no Romantismo Inglês” 65 Maria Zulmira Castanheira, “O Papel Mediador da Imprensa Periódica na Divulgação da Cultura Britânica em Portugal ao Tempo do Romantismo (1836-1865): Matérias e Imagens” 76 João Paulo Ascenso P. -

Charlotte Smith, William Cowper, and William Blake: Some New Documents

ARTICLE Charlotte Smith, William Cowper, and William Blake: Some New Documents James King Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly, Volume 13, Issue 2, Fall 1979, pp. 100-101 100 CHARLOTTE SMITH, WILLIAM COWPER, AND WILLIAM BLAKE: SOME NEW DOCUMENTS JAMES KING lthough her reputation is somewhat diminished Rose, of 25 April 1806 (Huntington)." As before, now, Charlotte Smith was the most celebrated Mrs. Smith is complaining about Hayley's neglect of A novelist in England in the early 1790s. Like her. George Romney, John Flaxman, William Cowper, and William Blake, Mrs. Smith was one of a number of I lose a great part of the regret I might writers and painters assisted by William Hayley in otherwise feel in recollecting, that a various ways. Mrs. Smith met Cowper at Eartham in mind so indiscriminating, who is now 1792, and the events of that friendship have been seized with a rage for a crooked figure= chronicled.1 Mrs. Smith never met William Blake, and maker & now for an engraver of Ballad only one excerpt from a letter linking them has pictures (the young Mans tragedy; & the previously been published. In this note, I should jolly Sailers Farewell to his true love Sally) —I dont mean the Hayleyan like to provide some additional information on Mrs. 5 Smith and Cowper, but I shall as well cite three collection of pretty ballads) —Such a unpublished excerpts from her correspondence in mind, can never be really attached; or which she comments on Blake. is the attachment it can feel worth having — In an article of 1952, Alan Dugald McKillop provided a n excellent account of Charlotte Smith's The "crooked figure=maker" is probably a reference letters.2 In the course of that essay, McKilloD to Flaxman and his hunch-back; despite the notes a facetiou s and denigrating remark of 20 March disclaimer, the engraver is more than likely to be 1806 (Hunt ington) about Hayley's Designs to a Series Blake. -

William Blake 1 William Blake

William Blake 1 William Blake William Blake William Blake in a portrait by Thomas Phillips (1807) Born 28 November 1757 London, England Died 12 August 1827 (aged 69) London, England Occupation Poet, painter, printmaker Genres Visionary, poetry Literary Romanticism movement Notable work(s) Songs of Innocence and of Experience, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, The Four Zoas, Jerusalem, Milton a Poem, And did those feet in ancient time Spouse(s) Catherine Blake (1782–1827) Signature William Blake (28 November 1757 – 12 August 1827) was an English poet, painter, and printmaker. Largely unrecognised during his lifetime, Blake is now considered a seminal figure in the history of the poetry and visual arts of the Romantic Age. His prophetic poetry has been said to form "what is in proportion to its merits the least read body of poetry in the English language".[1] His visual artistry led one contemporary art critic to proclaim him "far and away the greatest artist Britain has ever produced".[2] In 2002, Blake was placed at number 38 in the BBC's poll of the 100 Greatest Britons.[3] Although he lived in London his entire life except for three years spent in Felpham[4] he produced a diverse and symbolically rich corpus, which embraced the imagination as "the body of God",[5] or "Human existence itself".[6] Considered mad by contemporaries for his idiosyncratic views, Blake is held in high regard by later critics for his expressiveness and creativity, and for the philosophical and mystical undercurrents within his work. His paintings William Blake 2 and poetry have been characterised as part of the Romantic movement and "Pre-Romantic",[7] for its large appearance in the 18th century. -

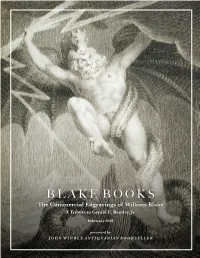

Blake Books, Contributed Immeasurably to the Understanding and Appreciation of the Enormous Range of Blake’S Works

B L A K E B O O K S The Commercial Engravings of William Blake A Tribute to Gerald E. Bentley, Jr. February 2018 presented by J O H N W I N D L E A N T I Q U A R I A N B O O K S E L L E R T H E W I L L I A M B L A K E G A L L E R Y B L A K E B O O K S The Commercial Engravings of William Blake A Tribute to Gerald E. Bentley, Jr. February 2018 Blake is best known today for his independent vision and experimental methods, yet he made his living as a commercial illustrator. This exhibition shines a light on those commissioned illustrations and the surprising range of books in which they appeared. In them we see his extraordinary versatility as an artist but also flashes of his visionary self—flashes not always appreciated by his publishers. On display are the books themselves, objects that are far less familiar to his admirers today, but that have much to say about Blake the artist. The exhibition is a small tribute to Gerald E. Bentley, Jr. (1930 – 2017), whose scholarship, including the monumental bibliography, Blake Books, contributed immeasurably to the understanding and appreciation of the enormous range of Blake’s works. J O H N W I N D L E A N T I Q U A R I A N B O O K S E L L E R 49 Geary Street, Suite 205, San Francisco, CA 94108 www.williamblakegallery.com www.johnwindle.com 415-986-5826 - 2 - B L A K E B O O K S : C O M M E R C I A L I L L U S T R A T I O N Allen, Charles. -

Charlotte Smith’S Own Death

Charlotte (Turner) Smith (1749-1806) by Ruth Facer Soon after I was 11 years old, I was removed to London, to an house where there were no books...But I found out by accident a circulating library; and, subscribing out of my own pocket money, unknown to the relation with whom I lived, I passed the hours destined to repose, in running through all the trash it contained. My head was full of Sir Charles, Sir Edwards, Lord Belmonts, and Colonel Somervilles, while Lady Elizas and Lady Aramintas, with many nymphs of inferior rank, but with names equally beautiful, occupied my dreams.[1] As she ran through the ‘trash’ of the circulating library, little could the eleven-year Charlotte Turner have imagined that she was to become one of the best-known poets and novelists of the late eighteenth century. In all, she was to write eleven novels, three volumes of poetry, four educational books for young people, a natural history of birds, and a history of England. Charlotte was born in 1749 to Nicholas Turner, a well-to-do country gentleman, and his wife, Anna. Her early years were spent at Stoke Place, near Guildford in Surrey and Bignor Park on the Arun in Sussex. The idyllic landscape of the South Downs was well known to her and was to recur in her novels and poetry time and again: Spring’s dewy hand on this fair summit weaves The downy grass, with tufts of Alpine flowers, And shades the beechen slopes with tender leaves, And leads the Shepherd to his upland bowers, Strewn with wild thyme; while slow-descending showers, Feed the green ear, and nurse the future sheaves! Sonnet XXXI (written in Farm Wood, South Downs in May 1784) Sadly this idyllic life was to end abruptly with the death of Anna Turner, leaving the four-year old Charlotte to be brought up by her aunt Lucy in London. -

John Boydell's Shakespeare Gallery and the Promotion of a National Aesthetic

JOHN BOYDELL'S SHAKESPEARE GALLERY AND THE PROMOTION OF A NATIONAL AESTHETIC ROSEMARIE DIAS TWO VOLUMES VOLUME I PHD THE UNIVERSITY OF YORK HISTORY OF ART SEPTEMBER 2003 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Volume I Abstract 3 List of Illustrations 4 Introduction 11 I Creating a Space for English Art 30 II Reynolds, Boydell and Northcote: Negotiating the Ideology 85 of the English Aesthetic. III "The Shakespeare of the Canvas": Fuseli and the 154 Construction of English Artistic Genius IV "Another Hogarth is Known": Robert Smirke's Seven Ages 203 of Man and the Construction of the English School V Pall Mall and Beyond: The Reception and Consumption of 244 Boydell's Shakespeare after 1793 290 Conclusion Bibliography 293 Volume II Illustrations 3 ABSTRACT This thesis offers a new analysis of John Boydell's Shakespeare Gallery, an exhibition venture operating in London between 1789 and 1805. It explores a number of trajectories embarked upon by Boydell and his artists in their collective attempt to promote an English aesthetic. It broadly argues that the Shakespeare Gallery offered an antidote to a variety of perceived problems which had emerged at the Royal Academy over the previous twenty years, defining itself against Academic theory and practice. Identifying and examining the cluster of spatial, ideological and aesthetic concerns which characterised the Shakespeare Gallery, my research suggests that the Gallery promoted a vision for a national art form which corresponded to contemporary senses of English cultural and political identity, and takes issue with current art-historical perceptions about the 'failure' of Boydell's scheme. The introduction maps out some of the existing scholarship in this area and exposes the gaps which art historians have previously left in our understanding of the Shakespeare Gallery. -

Italy Under the Golden Dome

Italy Under the Golden Dome The Italian-American Presence at the Massachusetts State House Italy Under the Golden Dome The Italian-American Presence at the Massachusetts State House Susan Greendyke Lachevre Art Collections Manager, Commonwealth of Massachusetts Art Commission, with the assistance of Teresa F. Mazzulli, Doric Docents, Inc. for the Italian-American Heritage Month Committee All photographs courtesy Massachusetts Art Commission. Fifth ed., © 2008 Docents R IL CONSOLE GENERALE D’ITALIA BOSTON On the occasion of the latest edition of the booklet “Italy Under the Golden Dome,” I would like to congratulate the October Italian Heritage Month Committee for making it available, once again, to all those interested to learn about the wonderful contributions that Italian artists have made to the State House of Massachusetts. In this regard I would also like to avail myself of this opportunity, if I may, to commend the Secretary of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, the Hon. William F. Galvin, for the cooperation that he has graciously extended to the Committee in this particular endeavor. Italians and Italian Americans are rightly proud of the many extraordinary works of art that decorate the State House, works that are either made by Italian artists or inspired by the Italian tradition in the field of art and architecture. It is therefore particularly fitting that the October Italian Heritage Month Committee has taken upon itself the task of celebrating this unique contribution that Italians have made to the history of Massachusetts. Consul General of Italy, Boston OCTOBER IS ITALIAN-AMERICAN HERITAGE MONTH On behalf of the Committee to Observe October as Italian-American Heritage Month, we are pleased and honored that Secretary William Galvin, in cooperation with the Massachusetts Art Commission and the Doric Docents of the Massachusetts State House, has agreed to publish this edition of the Guide. -

William Blake Henry Fuseli Auckland City Art Gallery

WILLIAM BLAKE ILLUSTRATIONS OF THE BOOK OF JOB HENRY FUSELI THE THREE WITCHES OF MACBETH AND ASSOCIATED WORKS AUCKLAND CITY ART GALLERY AUGUST 8 - OCTOBER 2 1980 WILLIAM BLAKE (1757-1827) As poet, watercolourist and engraver, Blake was the creator of an idiosyncratic mythology. Born of a lower middle class merchant family, Blake had no academic training, but attended Henry Par's preparatory drawing school from 1767 until his apprenticeship in 1772 to James Basire, engraver to the Society of Antiquaries. At Westminster Abbey,Blake made drawings for Gough's Sepulchral Monuments in Great Britain (1786), thereby immersing himself in the mediaeval tradition, with which he found a spiritual affinity. In 1782 Blake married and moved to Leicester Fields in London, where he completed and published in 1783 his first work, Poetical Sketches. In these early years he developed lasting friendships with the painters Barry, Fuseli and Flaxman, and for a while shared Flaxman's preoccupation with classical art. For his next major publication, Songs of Innocence, completed in 1789, Blake invented a new engraving technique whereby lyrics and linear design could be reproduced simultaneously in several stages in the copper plate. The resulting prints were then hand-coloured. This complete fusion of tint and illustration recalls mediaeval illuminated manuscripts, from which Blake derived obvious inspiration. From 1790 until 1800 Blake lived in Lambeth and produced books, thematically characterised by energetic protest against eighteenth century morality (The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, 1790-3) and against political authority (Ammca 1793, and The French Revolution, 1791). These works corroborate Blake's radicalism, which was demonstrated by his sympathy with Swedenborg in religion, with Mary Wollstonecaft in education, and with the Jacobins during the French Revolution. -

Guy Peppiatt Fine Art British Portrait and Figure

BRITISH PORTRAIT AND FIGURE DRAWINGS 2020 BRITISH PORTRAIT AND FIGURE DRAWINGS BRITISH PORTRAIT AND FIGURE DRAWINGS 2020 GUY PEPPIATT FINE ART FINE GUY PEPPIATT GUY PEPPIATT FINE ART LTD Riverwide House, 6 Mason’s Yard Duke Street, St James’s, London SW1Y 6BU GUY PEPPIATT FINE ART Guy Peppiatt started his working life at Dulwich Picture Gallery before joining Sotheby’s British Pictures Department in 1993. He soon specialised in early British drawings and watercolours and took over the running of Sotheby’s Topographical sales. Guy left Sotheby’s in 2004 to work as a dealer in early British watercolours and since 2006 he has shared a gallery on the ground floor of 6 Mason’s Yard off Duke St., St. James’s with the Old Master and European Drawings dealer Stephen Ongpin. He advises clients and museums on their collections, buys and sells on their behalf and can provide insurance valuations. He exhibits as part of Master Drawings New York every January as well as London Art Week in July and December. Email: [email protected] Tel: 020 7930 3839 or 07956 968 284 Sarah Hobrough has spent nearly 25 years in the field of British drawings and watercolours. She started her career at Spink and Son in 1995, where she began to develop a specialism in British watercolours of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. In 2002, she helped set up Lowell Libson Ltd, serving as co- director of the gallery. In 2007, Sarah decided to pursue her other passion, gardens and plants, and undertook a post graduate diploma in landscape design. -

Portrait of a Gentleman, Half-Length, Wearing a Dark Coat and White Stock Oil on Canvas 76.2 X 63.5 Cm (30 X 25 In)

George Romney (Dalton 1734 - Kendal 1802) Portrait of a Gentleman, Half-Length, Wearing a Dark Coat and White Stock oil on canvas 76.2 x 63.5 cm (30 x 25 in) Throughout the second half of the eighteenth century, George Romney was one of the most sought-after portraitists in Britain, though his portraits were not quite as dear as those by Joshua Reynolds and Thomas Gainsborough he was nevertheless recognised as their only rival. In fact, as he was more inclined to Neoclassicism than many of his British contemporaries, at the height of his career Romney was the most fashionable portraitist in British society, with his sitters always appearing elegant and beautiful. In Portrait of a Gentleman, Half-Length, Wearing a Dark Coat and White Stock one can see why Romney’s services were so in demand. The gentleman sits, half turned towards the viewer, meeting our gaze calmly and confidently. His face is idealised, soft and unblemished, with his hair brushed back from his forehead, as was the fashion. His clothing is simple and fashionable and tells the viewer that we are looking at a tasteful, elegant and refined individual. By using such a dark, stark background, Romney focuses our attention onto his subject. English portraiture flourished in the late eighteenth century, when not only aristocrats, but also lesser 125 Kensington Church Street, London W8 7LP United Kingdom www.sphinxfineart.com Telephone +44(0)20 7313 8040 Fax: +44 (0)20 7229 3259 VAT registration no 926342623 Registered in England no 06308827 nobles, merchants and officers commissioned portraits of themselves, their wives and children. -

William Blake Large Print Guide

WILLIAM BLAKE 11 September 2019 – 2 February 2020 LARGE PRINT GUIDE Please return to the holder CONTENTS Room 1 ................................................................................3 Room 2 ..............................................................................44 Room 3 ............................................................................ 105 Room 4 ............................................................................ 157 Projection room ............................................................... 191 Room 5 ............................................................................ 195 Find out more ..................................................................254 Credits .............................................................................256 Floor plan ........................................................................259 2 ROOM 1 BLAKE BE AN ARTIST Entering the room, clockwise Quote on the wall The grand style of Art restored; in FRESCO, or Water-colour Painting, and England protected from the too just imputation of being the Seat and Protectress of bad (that is blotting and blurring) Art. In this Exhibition will be seen real Art, as it was left us by Raphael and Albert Durer, Michael Angelo, and Julio Romano; stripped from the Ignorances of Rubens and Rembrandt, Titian and Correggio. William Blake, ‘Advertisement’ for his one-man exhibition, 1809 4 WILLIAM BLAKE The art and poetry of William Blake have influenced generations. He has inspired many creative people, political radicals -

George Romney's Death of General Wolfe (Romantik 2016 06, 51-62)

Paley, Journal for the Study of Romanticisms (2017), Volume 06, 51-62, DOI 10.14220/JSOR.2017.06.51 Morton D. Paley George Romney’s Death of General Wolfe Abstract George Romney (1734–1802) became famous as aportrait artist but also aspired to history painting throughout his career. In 1760 he exhibited the first painting to commemoratethe death of General James Wolfe, who had died the previous year during the battle for Quebec. It wasalso the first history painting – if we understand by this term the dramatic depiction of a heroic action – to dare to depictits subject in modern dress. The objectofconsiderable controversy, it neverthelessgainedaspecialpremiumand wasbought by aprominent collector. It also set aprecedentfor following treatments of its subject by Edward Penny, Benjamin West, and JamesBarry. It wastaken to India by asubsequent owner, and its location is now unknown. Using Romney’ssketches and contemporary descriptions as a basis, in this paper Ireconstruct the appearance of this paintingand discuss its importance in the historyofBritish art. Keywords George Romney, James Wolfe, History, Painting, Exhibitions After news of General James Wolfe’sdeath in the British victory at Quebec reached England on October 17, 1759, there wasanoutpouring of prose and poetry eulogizing and exalting him.1 The first works of art honoring the general were full-sized marble busts (c. 1760) by Joseph Wilton, in marble (National Gallery of Canada) and in plaster (National Portrait Gallery), in which, following tradition, Wolfe is presented as an ancient Roman (fig. 1).2 Credit for the first painting of the death of Wolfe, however, belongs to ayoung man from the provinces who had arrived in London in the previous year, who earned his living 1See Alan McNairn, Behold the Hero: General Wolfe andthe Arts in the Eighteenth Century (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 1997, 3–19.