Independence and After

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scripture Translations in Kenya

/ / SCRIPTURE TRANSLATIONS IN KENYA by DOUGLAS WANJOHI (WARUTA A thesis submitted in part fulfillment for the Degree of Master of Arts in the University of Nairobi 1975 UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI LIBRARY Tills thesis is my original work and has not been presented ior a degree in any other University* This thesis has been submitted lor examination with my approval as University supervisor* - 3- SCRIPTURE TRANSLATIONS IN KENYA CONTENTS p. 3 PREFACE p. 4 Chapter I p. 8 GENERAL REASONS FOR THE TRANSLATION OF SCRIPTURES INTO VARIOUS LANGUAGES AND DIALECTS Chapter II p. 13 THE PIONEER TRANSLATORS AND THEIR PROBLEMS Chapter III p . ) L > THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN TRANSLATORS AND THE BIBLE SOCIETIES Chapter IV p. 22 A GENERAL SURVEY OF SCRIPTURE TRANSLATIONS IN KENYA Chapter V p. 61 THE DISTRIBUTION OF SCRIPTURES IN KENYA Chapter VI */ p. 64 A STUDY OF FOUR LANGUAGES IN TRANSLATION Chapter VII p. 84 GENERAL RESULTS OF THE TRANSLATIONS CONCLUSIONS p. 87 NOTES p. 9 2 TABLES FOR SCRIPTURE TRANSLATIONS IN AFRICA 1800-1900 p. 98 ABBREVIATIONS p. 104 BIBLIOGRAPHY p . 106 ✓ - 4- Preface + ... This is an attempt to write the story of Scripture translations in Kenya. The story started in 1845 when J.L. Krapf, a German C.M.S. missionary, started his translations of Scriptures into Swahili, Galla and Kamba. The work of translation has since continued to go from strength to strength. There were many problems during the pioneer days. Translators did not know well enough the language into which they were to translate, nor could they get dependable help from their illiterate and semi literate converts. -

Kaya Hip-Hop in Coastal Kenya: the Urban Poetry of UKOO FLANI

Page 1 of 46 Kaya Hip-Hop in Coastal Kenya: The Urban Poetry of UKOO FLANI By: Divinity LaShelle Barkley [email protected] Academic Director: Athman Lali Omar I.S.P. Advisor: Professor Mohamed Abdulaziz S.I.T. Kenya, Fall 2007 Coastal Cultures & Swahili Studies Kaya Hip Hop in Coastal Kenya Fall 2007 ISP, SIT Kenya By: Divinity L. Barkley Page 2 of 46 Table of Contents Acknowledgements………………………………………..………………….page 3 Abstract……………………………………………..…………………………page 4 Introduction…………………………………..……………………………pages 5-8 Hip-Hop & Kenyan Youth Culture Research Problem Status of Hip-Hop in Kenya Hypotheses The Setting……………………………….………………………………pages 9-10 Methodology: Data Collection……………………………………..…pages 10-12 Biases and Assumptions………………………..………...…………...pages 13-14 Discussion & Analysis…………………………………………………pages 14-38 Ukoo Flani ni nani? Kaya Hip-Hop Traditional Role of Music in African Culture Genesis of Rap/Hip-hop in American Ghettoes The Ties That Bind Kenyan Radio The Maskani Ghetto Life Will the real Ukoo Flani please stand up? Urban Poetry: Analyzing Ukoo Flani’s Lyrics Conclusion…………………………..……………………….…………pages 38-42 Conclusion Part I: The Future of Ukoo Flani Conclusion Part II: Hypotheses Results Conclusion Part III: Recommendations for Future SIT Students Bibliography………………………………………………..…………..pages 43-44 Interview/Meeting Schedule………………………………………………page 45 ISP Review Sheet…………….……………………………………….……page 46 Kaya Hip Hop in Coastal Kenya Fall 2007 ISP, SIT Kenya By: Divinity L. Barkley Page 3 of 46 Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank the entire Ukoo Flani crew for their contributions to my project. I am fascinated by your amazing talent and dedication to making positive music to inspire future generations. I am amazed at what you have been able to accomplish despite limited access to resources. -

Political Parties and Party Systems in Kenya

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Elischer, Sebastian Working Paper Ethnic Coalitions of Convenience and Commitment: Political Parties and Party Systems in Kenya GIGA Working Papers, No. 68 Provided in Cooperation with: GIGA German Institute of Global and Area Studies Suggested Citation: Elischer, Sebastian (2008) : Ethnic Coalitions of Convenience and Commitment: Political Parties and Party Systems in Kenya, GIGA Working Papers, No. 68, German Institute of Global and Area Studies (GIGA), Hamburg This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/47826 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort -

Impacts of Colonial Policies and Practices on Kamba Song and Dance up to 1945

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 25, Issue 4, Series. 5 (April. 2020) 18-25 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org Impacts of Colonial Policies and Practices on Kamba Song and dance Up To 1945. Kilonzo Josephine Katiti Abstract: Song and dance are powerful cultural medium in any society. This is especially so in countries where other forms of communication and cultural expression, such as written word are not yet fully developed. The history of many developing countries where colonial domination was evidenced indicates that the colonized people were always able to express themselves through song and dance in complete defiance of the oppressor. Song and dance was used not just as a preserver but also a transmitter of history. This paper seeks to assess the impacts of colonial policies and practices on Kamba song and dance up to 1945. Due to the view of the colonizers that the Africans were primitive and barbaric the colonial masters introduced policies which favored them. These policies led to a definite change of the content of Kamba songs sang at that time. In order to accommodate the changes to the environment, culture, political and economic life of the community, several changes were experienced at the time. This paper present the findings from the study that was conducted on the Kamba of eastern Kenya and shows that over time the community evolved dynamic song and dance styles that responded to the changes within their midst. This paper hopes to contribute to scholarship in terms of the key contribution of Kamba song to the historical transformation of society. -

Post-Colonialism and the Politics of Kenya (Review)

3RVWFRORQLDOLVPDQGWKHSROLWLFVRI.HQ\D UHYLHZ Peter Wafula Wekesa Eastern Africa Social Science Research Review, Volume 18, Number 1, January 2002, pp. 109-114 (Article) 3XEOLVKHGE\2UJDQL]DWLRQIRU6RFLDO6FLHQFH5HVHDUFKLQ(DVWHUQ DQG6RXWKHUQ$IULFD DOI: 10.1353/eas.2002.0004 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/eas/summary/v018/18.1wekesa.html Access provided by Kenyatta University. Library (4 Nov 2014 08:22 GMT) Book Reviews Ahluwalia D. Pal, Post-colonialism and the politics of Kenya (New York: Nova Science Publishers, Inc.) 1996, 217 pp. Post-colonialism as a framework of analysis remains subject to debate and controversy. Although post-colonialism has been around for close to two decades, it has in recent times been a fiercely contested and debated paradigm. Given its newness and elegance in the world of academic discourse, it is not surprising that its reception has been characterized by a great deal of excitement, confusion and in many cases scepticism. Debates surrounding the study have laid claims to questions of the legitimacy of post-colonialism as a separate analytical entity in the academic discourse, its validity as a theoretical formulation as well as its disciplinary boundaries and political implications. Also, the prefix ‘post’ has complicated matters as it implies an ‘aftermath’ in two senses - temporal, as in coming after, and ideological, as in supplanting. It is the second implication that the critics of the study have found contestable. The contestation has been on the dividing line between what is colonial and its link to what counts as post-colonial. The argument has been that if the inequities of colonial rule have not been erased, it is perhaps premature to proclaim the demise of colonialism. -

Race for Distinction a Social History of Private Members' Clubs in Colonial Kenya

Race for Distinction A Social History of Private Members' Clubs in Colonial Kenya Dominique Connan Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of History and Civilization of the European University Institute Florence, 09 December 2015 European University Institute Department of History and Civilization Race for Distinction A Social History of Private Members' Clubs in Colonial Kenya Dominique Connan Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of History and Civilization of the European University Institute Examining Board Prof. Stephen Smith (EUI Supervisor) Prof. Laura Lee Downs, EUI Prof. Romain Bertrand, Sciences Po Prof. Daniel Branch, Warwick University © Connan, 2015 No part of this thesis may be copied, reproduced or transmitted without prior permission of the author Race for Distinction. A Social History of Private Members’ Clubs in Colonial Kenya This thesis explores the institutional legacy of colonialism through the history of private members clubs in Kenya. In this colony, clubs developed as institutions which were crucial in assimilating Europeans to a race-based, ruling community. Funded and managed by a settler elite of British aristocrats and officers, clubs institutionalized European unity. This was fostered by the rivalry of Asian migrants, whose claims for respectability and equal rights accelerated settlers' cohesion along both political and cultural lines. Thanks to a very bureaucratic apparatus, clubs smoothed European class differences; they fostered a peculiar style of sociability, unique to the colonial context. Clubs were seen by Europeans as institutions which epitomized the virtues of British civilization against native customs. In the mid-1940s, a group of European liberals thought that opening a multi-racial club in Nairobi would expose educated Africans to the refinements of such sociability. -

Notes and References

Notes and References 1 The Foundation of Kenya Colony I. P[ublic] R[ecord] O[ffice] Kew CO 533/234 ff 432-44. Kenya was how Johann Krapf, the German missionary who was in 1849 the first white man to see the mountain, transliterated the Kamba pronunciation of the Kikuyu name for it, Kirinyaga. The Kamba substituted glottal stops for intermediate consonants, hence 'Ki-i-ny-a'. T. C. Colchester, 'Origins of Kenya as the Name of the Country', Rhodes House. Mss Afr s.1849. 2. PRO CO 822/3117 Malcolm MacDonald to Duncan Sandys. Secret and Personal. 18 September 1963. 3. The new rail routes in question were the Uasin Gishu line and the Thika extension. M. F. Hill, Permanent Way. The StOlY of the Kenya and Uganda Railway (Nairobi: East African Railways and Harbours, 2nd edn 1961), p. 392. 4. Daily Sketch, 5 July 1920, p. 5. 5. Sekallyolya ('the crane [or stork] looking out on the world') was first printed in Nairobi in the Luganda language in 1921. From time to time it brought out editions in Swahili and for special occasions in English. Harry Thuku's Tangazo was the first Kenya African single sheet newsletter. 6. Interview with James Beauttah, Fort Hall, 1964. Beauttah was one of the first English-speaking African telephone operators. He claimed to be the first African to have electricity in his house. 7. PRO FO 2/377 A. Gray to FO, 16 February 1900, 'Memo on Report of Law Officers of the Crown reo East Africa and Uganda Protector ates'. The effect of the opinion of the law officers is that Her Majesty has, by virtue of her Protectorate, entire control over all lands unappropriated .. -

ELECTIONS and VIOLENCE: the Kenyan Case

By Paul Okong’o Why are elections in Kenya associated with death and tragedy? At what point in our history as nation, did bloodletting become part and parcel of the Presidential and General elections? In Kenya today, elections are synonymous with shootings, death, sorrow and destructions in some parts of the country. Kisumu and the counties of Homa Bay, Siaya and Migori, where the Luo ethnic group is dominant have become associated with police shootings and killings during and after elections. A look into the history of elections in Kenya can help us understand the triggers of these conflicts. Karl Marx said, “History repeats itself, first as tragedy and second as farce”. From 1960 to 1963 in the years leading to independence, the battleground was a contest between the two nationalist political parties, the Kenya African National Union (KANU) and the Kenya African Democratic Union (KADU), competing for the Senate, Parliamentary or Regional assembly seats. The competing political ideologies were for a Centralist Government as espoused by KANU and Majimbo (Federalism) as propounded by KADU. There were other parties too, Paul Ngei’s African Peoples Party (APP) and Sir Michael Blundell’s New Kenya Party but the real supremacy battle was between KANU and KADU. In 1963, KANU consisted of the Agikuyu and Luo led by Jomo Kenyatta, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga and Tom Mboya among others. KADU was led by Ronald Ngala, Daniel arap Moi, Masinde Muliro and Martin Shikuku and was composed of the Coastal peoples, the Kalenjin of the Rift Valley and parts of Western Province with the Bukusu and a smattering of other Luhya sub-tribes. -

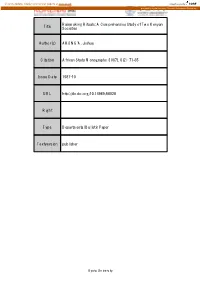

A Comprehensive Study of Two Kenyan Societies Author(S)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kyoto University Research Information Repository Rainmaking Rituals: A Comprehensive Study of Two Kenyan Title Societies Author(s) AKONG'A, Joshua Citation African Study Monographs (1987), 8(2): 71-85 Issue Date 1987-10 URL http://dx.doi.org/10.14989/68028 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University African Study "'tonographs, 8(2): 71-85, October 1987 71 RAINMAKING RITUALS: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF TWO KENYAN SOCIETIES Joshua AKONG'A Instilute ofAfrican Stlldies. Unh'ersity ofNairobi ABSTRACf A comparative examination of the public rainmaking rituals in Kitui District and the secret rainmaking rituals in Bunyore location of Kakamega District, both in Kenya, reveals that public rituals are more susceptible to rapid social change than those of secret. Secondly. although rainmaking rituals are a response to scarcity or unreliability that are rain fall. such rituals can be found even in the areas of adequate rainfall either because the people once lived in an area of rainfall scarcity or the rainmakers are strangers who came from such areas. Thirdly, the efficacy of rainmaking rituals is based on faith, and due to the involvement of the supernatural, they have socio-psychological implications on the participants. Key Words: Rainmaking; Processions; Magic; Prophesy; Occult. INTRODUCTION Sir James George Frazer who wrote widely on the types and practices of magic, considered rainfall rituals as falling under the purview of magic. This is because the purpose of rainfall rituals is to influence weathercondition~ in order to cause rain or to cause drought either for the general good or destruction ofthe people in the specific society in which there is a belief in man's ability to influence weather conditions. -

Who Owns the Land? Blood and Soil Issues in the Kenyan Rift Valley

WHO OWNS THE LAND? BLOOD AND SOIL ISSUES IN THE KENYAN RIFT VALLEY PART 1: The passion with which millions of citizens valued their presidential vote in the stolen 2007 presidential elections can be reflected in scenes of the bloody post-election clashes today that engulfed Rift Valley, Nyanza, Coast, Nairobi, Western and to a less extent in other parts of the country. Nakuru was the latest epicenter of inter ethnic murders. The violent reactions to rigged elections may reflect the pain of deep and historically rooted injustices some of which predate Kenya’s independence in 1963. They are in fact motivated and exacerbated by landlessness, joblessness, and poverty believed to be heavily contributed towards by the prevailing political status quo that has dominated Kenya since independence. This is a system that has continuously perpetrated, in successive fashion, socio- economic injustices that have been seamlessly transferred from one power regime to the next. The Land issue With a fast growing population in Kenya, limited resources including land and jobs, have severely been put in extreme pressure. Responsive political operatives cognizant of this reality have appreciated the importance of incorporating progressive policies that seek to aggressively address poverty, landlessness, unequal distribution of resources and unemployment, as a matter of priority (in their party manifestoes) if any social stability is to be maintained in Kenya. Without doubt, the opposition party ODM sold an attractive campaign package that sought to address historic land injustices, unemployment, inequitable resource sharing and poverty through a radical constitutional transformation, under the framework of the people-tailored Bomas Constitution Draft. -

History of the Parliament of Kenya

The National Assembly History of The Parliament of Kenya FactSheet No.24 i| FactSheet 24: History of The Parliament of Kenya History of The Parliament of Kenya FactSheet 24: History of The Parliament of Kenya Published by: The Clerk of the National Assembly Parliament Buildings Parliament Road P.O. Box 41842-00100 Nairobi, Kenya Tel: +254 20 221291, 2848000 Email: [email protected] www.parliament.go.ke © The National Assembly of Kenya 2017 Compiled by: The National Assembly Taskforce on Factsheets, Online Resources and Webcasting of Proceedings Design & Layout: National Council for Law Reporting |ii The National Assembly iii| FactSheet 24: History of The Parliament of Kenya Acknowledgements This Factsheet on History of the Parliament of Kenya is part of the Kenya National Assembly Factsheets Series that are supposed to enhance public understanding, awareness and knowledge of the work of the Assembly and its operations. It is intended to serve as easy guide for ready reference by Members of Parliament, staff and the general public. The information contained here is not exhaustive and readers are advised to refer to the original sources for further information. This work is a product of concerted efforts of all the Directorates and Departments of the National Assembly, and the Parliamentary Joint Services. Special thanks go to the Members of the National Assembly Taskforce on Factsheets, Online Resources and Webcasting of Proceedings, namely, Mr. Kipkemoi arap Kirui (Team Leader), Mr. Emejen Lonyuko, Mr. Robert Nyaga, Mr. Denis Abisai, Mr. Stephen Mutungi, Mr. Bonnie Mathooko, Maj. (Rtd.) Bernard Masinde, Mr. Enock Bosire, and Ms. Josephine Karani. -

Journal of Arts & Humanities

Journal of Arts & Humanities Volume 07, Issue 11, 2018: 58-67 Article Received: 06-09-2018 Accepted: 02-10-2018 Available Online: 23-11-2018 ISSN: 2167-9045 (Print), 2167-9053 (Online) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18533/journal.v7i10.1491 Pioneering a Pop Musical Idiom: Fifty Years of the Benga Lyrics 1 in Kenya Joseph Muleka2 ABSTRACT Since the fifties, Kenya and Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) have exchanged cultural practices, particularly music and dance styles and dress fashions. This has mainly been through the artistes who have been crisscrossing between the two countries. So, when the Benga musical style developed in the sixties hitting the roof in the seventies and the eighties, contestations began over whether its source was Kenya or DRC. Indeed, it often happens that after a musical style is established in a primary source, it finds accommodation in other secondary places, which may compete with the originators in appropriating the style, sometimes even becoming more committed to it than the actual primary originators. This then begins to raise debates on the actual origin and/or ownership of the form. In situations where music artistes keep shuttling between the countries or regions like the Kenya and DRC case, the actual origin and/or ownership of a given musical practice can be quite blurred. This is perhaps what could be said about the Benga musical style. This paper attempts to trace the origins of the Benga music to the present in an effort to gain clarity on a debate that has for a long time engaged music pundits and scholars.