The Sun's Effect on Climate: Content Background Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter Outline Thinking Ahead 4 EARTH, MOON, AND

Chapter 4 Earth, Moon, and Sky 103 4 EARTH, MOON, AND SKY Figure 4.1 Southern Summer. As captured with a fish-eye lens aboard the Atlantis Space Shuttle on December 9, 1993, Earth hangs above the Hubble Space Telescope as it is repaired. The reddish continent is Australia, its size and shape distorted by the special lens. Because the seasons in the Southern Hemisphere are opposite those in the Northern Hemisphere, it is summer in Australia on this December day. (credit: modification of work by NASA) Chapter Outline 4.1 Earth and Sky 4.2 The Seasons 4.3 Keeping Time 4.4 The Calendar 4.5 Phases and Motions of the Moon 4.6 Ocean Tides and the Moon 4.7 Eclipses of the Sun and Moon Thinking Ahead If Earth’s orbit is nearly a perfect circle (as we saw in earlier chapters), why is it hotter in summer and colder in winter in many places around the globe? And why are the seasons in Australia or Peru the opposite of those in the United States or Europe? The story is told that Galileo, as he left the Hall of the Inquisition following his retraction of the doctrine that Earth rotates and revolves about the Sun, said under his breath, “But nevertheless it moves.” Historians are not sure whether the story is true, but certainly Galileo knew that Earth was in motion, whatever church authorities said. It is the motions of Earth that produce the seasons and give us our measures of time and date. The Moon’s motions around us provide the concept of the month and the cycle of lunar phases. -

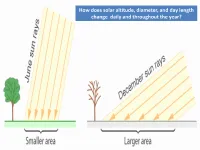

How Does Solar Altitude, Diameter, and Day Length Change Daily and Throughout the Year?

How does solar altitude, diameter, and day length change daily and throughout the year? Let’s prove distance doesn’t matter in seasons by investigating SOLAR ALTITUDE, DAY LENGTH and SOLAR DISTANCE… Would the sun have the same appearance if you observed it from other planets? Why do we see the sun at different altitudes throughout the day? We use the altitude of the sun at a time called solar “noon” because of daily solar altitude changes from the horizon at sunrise and sunset to it’s maximum daily altitude at noon. If you think solar noon is at 12:00:00, you’re mistaken! Solar “noon” doesn’t usually happen at clock-noon at your longitude for lots of reasons! SOLAR INTENSITY and ALTITUDE - Maybe a FLASHLIGHT will help us see this relationship! Draw the beam shape for 3 solar altitudes in your notebooks! How would knowing solar altitude daily and seasonally help make solar panels (collectors)work best? Where would the sun have to be located to capture the maximum amount of sunlight energy? Draw the sun in the right position to maximize the light it receives on panel For the northern hemisphere, in which general direction would they be pointed? For the southern hemisphere, in which direction would they be pointed? SOLAR PANELS at different ANGLES ON GROUND How do shadows show us solar altitude? You used a FLASHLIGHT and MODELING CLAY to show you how SOLAR INTENSITY, ALTITUDE, and SHADOW LENGTH are related! Using at least three solar altitudes and locations, draw your conceptual model of this relationship in your notebooks… Label: Sun compass direction Shadow compass direction Solar altitude Shadow length (long/short) Sun intensity What did the lab show us about how SOLAR ALTITUDE, DIAMETER, & DAY LENGTH relate to each other? YOUR GRAPHS are PROBABLY the easiest way to SEE the RELATIONSHIPS. -

Lecture 6: Where Is the Sun?

4.430 Daylighting Massachusetts Institute of Technology Christoph Reinhart Department of Architecture 4.430 Where is the sun? Building Technology Program Goals for This Week Where is the sun? Designing Static Shading Systems MIT 4.430 Daylighting, Instructor C Reinhart 1 1 MISC Meeting on group projects Reduce HDR image size via pfilt –x 800 –y 550 filne_name_large.pic > filename_small>.pic Note: pfilt is a Radiance program. You can find further info on pfilt by googeling: “pfilt Radiance” MIT 4.430 Daylighting, Instructor C Reinhart 2 2 Daylight Factor Hand Calculation Mean Daylight Factor according to Lynes Reinhart & LoVerso, Lighting Research & Technology (2010) Move into the building, design the facade openings, room dimensions and depth of the daylit area. Determine the required glazing area using the Lynes formula. A glazing = required glazing area A total = overall interior surface area (not floor area!) R mean = area-weighted mean surface reflectance vis = visual transmittance of glazing units = sun angle 3 ‘Validation’ of Daylight Factor Formula Reinhart & LoVerso, Lighting Research & Technology (2010) Graph of mean daylighting factor according to Lynes formula v. Radiance removed due to copyright restrictions. Source: Figure 5 in Reinhart, C. F., and V. R. M. LoVerso. "A Rules of Thumb Based Design Sequence for Diffuse Daylight." Lighting Research and Technology 42, no. 1 (2010): 7-32. Comparison to Radiance simulations for 2304 spaces. Quality control for simulations. LEED 2.2 Glazing Factor Formula Graph of mean daylighting factor according to LEED 2.2 v. Radiance removed due to copyright restrictions. Source: Figure 11 in Reinhart, C. F., and V. -

The Solar Resource

CHAPTER 7 THE SOLAR RESOURCE To design and analyze solar systems, we need to know how much sunlight is available. A fairly straightforward, though complicated-looking, set of equations can be used to predict where the sun is in the sky at any time of day for any location on earth, as well as the solar intensity (or insolation: incident solar Radiation) on a clear day. To determine average daily insolation under the com- bination of clear and cloudy conditions that exist at any site we need to start with long-term measurements of sunlight hitting a horizontal surface. Another set of equations can then be used to estimate the insolation on collector surfaces that are not flat on the ground. 7.1 THE SOLAR SPECTRUM The source of insolation is, of course, the sun—that gigantic, 1.4 million kilo- meter diameter, thermonuclear furnace fusing hydrogen atoms into helium. The resulting loss of mass is converted into about 3.8 × 1020 MW of electromagnetic energy that radiates outward from the surface into space. Every object emits radiant energy in an amount that is a function of its tem- perature. The usual way to describe how much radiation an object emits is to compare it to a theoretical abstraction called a blackbody. A blackbody is defined to be a perfect emitter as well as a perfect absorber. As a perfect emitter, it radiates more energy per unit of surface area than any real object at the same temperature. As a perfect absorber, it absorbs all radiation that impinges upon it; that is, none Renewable and Efficient Electric Power Systems. -

What Causes the Seasons? These Images of the Sun Were Taken 6 Months Apart

2/11/09 We can recognize solstices and equinoxes by If you are located in the continental U.S. on the first Sun’s path across sky: day of October, how will the position of the Sun at noon be different two weeks later? Summer solstice: Highest path, rise and set at most A. It will have moved toward the north. extreme north of due east. B. It will have moved to a position higher in the sky. C. It will stay in the same position. Winter solstice: Lowest D. It will have moved to a position closer to the path, rise and set at most extreme south of due horizon. east. E. It will have moved toward the west. Equinoxes: Sun rises precisely due east and sets precisely due west. NORTH For an observer in the Shadow Under which of the following circumstances will plot A continental U.S., which of Shadow plot B a vertical flagpole not cast a shadow as seen WEST from the continental United States? the three shadow plots, EAST shown at right, correctly Shadow plot C depicts the Sun’s motion for SOUTH A. every day at noon one day? B. every day at the time when the sun is highest in the sky C. when the sun is highest in the sky on the summer A. Shadow plot A solstice B. Shadow plot B C. Shadow plot C D. when the sun is highest in the sky on the winter solstice D. More than one of the plots are possible, on different days of E. -

Sunearthtools.Com Tools for Consumers and Designers of Solar Home Tools Solar Sun Position Photovoltaic Payback Photovoltaic FAQ Sunrise Sunset Calendar

Sun position chart, solar path diagram, solar angle declination zenith, hour sunrise sunset ... Page 1 of 6 SunEarthTools.com Tools for consumers and designers of solar Home Tools Solar Sun Position Photovoltaic payback Photovoltaic FAQ SunRise SunSet Calendar Home > Solar > Sun Position 19:41 | Thursday 14 February 2013 select your points search 34.393751, -118.585747 34° 23' 37.504" N 118° 35' 8.689" W SunRise: 06:40:11 * 105.02° | SunSet: 17:37:16 * 255.17° | 26039 Sandburg Place, Stevenson Ranch, CA 91381, USA Home Name execute Solar Disk Analemma Solstice Photovoltaic payback year month day hour minute See Todays Mortgage Rates Sun Position www.MortgageRates.LowerMyBills.com 2013 02 14 10 41 Time CO2 Emissions Rates Hit New Lows at 2.5%(2.9%APR) FHA Cuts Mortgage Requirement! GMT-8 DST Default zone Unit of measure converter Mode: sun path Full interactive map Interactive Map Distance Coordinates conversion SunRise SunSet Calendar Photovoltaic FAQ Insert this map tool in your site This work is licenced under a Creative Commons Licence Back to top Content | Data + Map | Chart Polar | Chart Cartesian | Table | You can copy some of the articles linking always the source. Visits: on Line: p:1 http://www.sunearthtools.com/dp/tools/pos_sun.php 2/14/2013 Sun position chart, solar path diagram, solar angle declination zenith, hour sunrise sunset ... Page 2 of 6 Back to top Content | Data + Map | Chart Polar | Chart Cartesian | Table | Back to top Content | Data + Map | Chart Polar | Chart Cartesian | Table | sun position Elevation Azimuth latitude longitude 34.393751° 118.585747° 14/02/2013 10:41 38.46° 152.35° N W Azimuth Azimuth Sunrise Sunset twilight Sunrise Sunset twilight -0.833° 06:40:11 17:37:16 105.02° 255.17° Civil twilight -6° 06:14:27 18:02:58 101.46° 258.74° http://www.sunearthtools.com/dp/tools/pos_sun.php 2/14/2013 Sun position chart, solar path diagram, solar angle declination zenith, hour sunrise sunset .. -

Analyzing an Earth-Sun Model to Explain the Stars Seen in The

EXPLORATION 1 Analyzing an Earth-Sun Model to Explain the Stars Seen in the Sky A group of stars that form a pattern is called a constellation. The constellation Ursa Major also has an inner pattern known as the Big Dipper. But if you look for the Big Dipper, you will see that it is not always in the same position in the night sky. In addition to the movement of the stars across the sky every night, their rising times change throughout the year. So the constellations visible in the early evening are different in winter, spring, summer, and fall. 3. Discuss When you look at the night sky, what do you see? The Big Dipper is one of the most familiar star patterns in the northern sky. It looks Changes in Stars Seen in the Night Sky like a ladle used to scoop water. Just as the sun appears to move in a path across the sky, stars in the night sky also appear to move. They seem to change locations nightly. 4. Why do the stars appear to move across the sky every night? A. Because Earth orbits the sun once a year. B. Because Earth tilts on its axis. C. Because Earth rotates once every 24 hours. 5. Act With your class, investigate why star patterns change yearly. • Several students form a large circle. They represent the stars in the night sky. One student represents the sun and stands in the center. One student represents Earth and stands between the stars and the sun. The head of the student who is Earth represents the North Pole of Earth. -

Sunlight and Seasons

Project ATMOSPHERE This guide is one of a series produced by Project ATMOSPHERE, an initiative of the American Meteorological Society. Project ATMOSPHERE has created and trained a network of resource agents who provide nationwide leadership in precollege atmospheric environment education. To support these agents in their teacher training, Project ATMOSPHERE develops and produces teacher’s guides and other educational materials. For further information, and additional background on the American Meteorological Society’s Education Program, please contact: American Meteorological Society Education Program 1200 New York Ave., NW, Ste. 500 Washington, DC 20005-3928 www.ametsoc.org/amsedu This material is based upon work initially supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. TPE-9340055. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. © 2012 American Meteorological Society (Permission is hereby granted for the reproduction of materials contained in this publication for non-commercial use in schools on the condition their source is acknowledged.) 2 Foreword This guide has been prepared to introduce fundamental understandings about the guide topic. This guide is organized as follows: Introduction This is a narrative summary of background information to introduce the topic. Basic Understandings Basic understandings are statements of principles, concepts, and information. The basic understandings represent material to be mastered by the learner, and can be especially helpful in devising learning activities in writing learning objectives and test items. They are numbered so they can be keyed with activities, objectives and test items. Activities These are related investigations. -

Winter Solstice (Shortest Track), and the Spring and Fall Equinoxes (Medium Track)

Solstice and Equinox (“Suntrack”) Season Model Philip Scherrer & Deborah Scherrer, Stanford Solar Center Introduction This physical model simulates the Sun’s tracks across the sky at summer solstice (longest track), winter solstice (shortest track), and the spring and fall equinoxes (medium track). A bead simulates the Sun moving from rising along the eastern horizon to setting on the western. The bead can be moved from track to track to demonstrate the solstices and equinoxes. The model is made to accurately represent the user’s latitude. Many people are confused about the meaning of solstices and equinoxes. Verbal descriptions are often inadequate because they are difficult to envision or overly technical. Imagery is helpful, but some have trouble understanding the perspective of the imagery. This physical model was developed (over years) to enhance the teaching of the solstice and equinox concepts, as well as being helpful in understanding solar alignments of cultural and archaeoastronomy sites. A quote from Cidney Webster, National Park Service: My program was a guided walk through the park and the topic was the winter solstice. ... I copied a diorama used by Dr. and Mrs. Scherrer during the training that demonstrated the Sun's position in the sky at different times of the year. This became my most effective teaching tool. Everyone loved the diorama!" Includes instructions for a simple, low-cost version made from paper plates and pipe cleaners. © Stanford University; permission to use granted for educational & noncommercial purposes -

Astronomy 110 Lecture 3

Astronomy 110 Lecture 3. Fall, 2005 Astronomy 110 1 1. The Earth’s axis points in the same direction (to Polaris) all year round, so its orientation relative to the Sun must change as Earth orbits the Sun. 2. Sunlight hits one hemisphere more directly than the other for half the year then the two hemispheres reverse. • AXIS TILT is the key to the seasons; without it, we would not have seasons on Earth. Fall, 2005 Astronomy 110 2 Fall, 2005 Astronomy 110 3 Antarctica December 21 June 21 Fall, 2005 Astronomy 110 4 Fall, 2005 Astronomy 110 5 How does the tilt of the Earth’s spin axis cause seasons? What causes the seasons? Fall, 2005 Astronomy 110 6 The Solstice and Eqinox can be recognized by the Sun’s path across sky: Summer solstice: highest path, rise and set at most extreme north of due east. Winter solstice: lowest path, rise and set at most extreme south of due east. Equinoxes: Sun rises precisely due east and sets precisely due west. Fall, 2005 Astronomy 110 7 Analemmas From APOD Crimea Delphi Fall, 2005 Astronomy 110 8 Fall, 2005 Astronomy 110 9 Fall, 2005 Astronomy 110 10 Why doesn’t distance matter? • The annual variation of the Earth-Sun distance — about 3%; is so small that it has little effect on temperatures on the Earth. • Note: more ocean and less land mass means, on average, less extreme seasonal temperature variations in the southern hemisphere. Fall, 2005 Astronomy 110 11 How do we mark the progression of the seasons? • There are four naturally defined annual season markers: Summer Solstice: Maximum northern excursion of the Sun Winter Solstice: Maximum southern excursion of the Sun Vernal Equinox: Sun crosses the Equator moving north. -

CSD Name: This Diagram Illustrates the Path of the Sun and the Altitude

Do Now Sci 88H -CSD Name: This diagram illustrates the path of the sun and the altitude of the noon sun on the celestial sphere for an observer in New York State (latitude 43N) at the beginning of each season. Label each month for the paths drawn in the diagram below Spring Summer Fall Winter NW SE NE 6/21 12/21 E 3/21 9/23 1. Which letter represents the path and altitude of the noon sunon ... a March 21? June 21? Shortest path - longest path - look @ duration of daylight A. & position of sunrise/set December 21? path D and 2. In November, the noon sun would most likely be between points 4 Fall season so after Equinox towards winter 3. In August, the noon sun would most likely be between points y after ist day of summer & soints B D and C olt equinok ! and 4. In May, the noon sun would most likely be between points - batter EQ - before ist day of summer 5. In January, the noon sun would most likely be between points 4 after ist day of winter & before equinox to and B ORD Base your answers to questions 32 through 3b on the diagram provided which shows observations made by a sailor who left his ship and landed on a small deserted island on June 21. The diagram represents the apparent path of the Sun and the position of Polaris, as observed by the sailor on this island. 4 to Sailor's Observations on the Deserted Island 80 90 Bolue 2 e = your Latitude 70 70 an 60 wluululuuluulutus 50 23. -

LAB # SEASONAL PATH of the SUN and LATITUDE Hemisphere

NAME; PERIOD; DATE; LAB # SEASONAL PATH OF THE SUN AND LATITUDE Hemisphere Model #3 at the Arctic Circle 1 OBJECTIVE Explain how latitude affects the seasonal path of the Sun. I) Path of the Sun and Latitude. In the previous activity we observed that the Sun’s path across the sky varies with the seasons. As its path changes, so too does the position of sunrise and sunset, the altitude of the noon sun, and the duration of sunlight (length of daylight). In New York State, the Winter Solstice (on December 21), marks the time when the noon sun is lowest in the sky and the period of daylight is the shortest. The Summer Solstice (on June 21), is the day when the noon sun is highest in the sky and the duration of daylight is the greatest. Although the noon sun is highest on this date, the sun will never be directly overhead (zenith position) in New York State. In only place where the sun is ever in the zenith position (90o altitude), is in the tropics. The tropics is anywhere between 23.5oN and 23.5oS latitude. The path of the sun during the equinoxes lies between the paths for the solstices. The equinoxes (equal nights) are the only time when the sun rises due east and set due west. It is also the date when the entire Earth experiences 12 hours of sunlight, regardless of your location. Is the path of the Sun the same in New York as it is at the Arctic Circle, or at the equator? Does latitude (distance north or south from the equator) affect the path that the sun takes across the sky? Above the Arctic Circle, is there still 12 hours of daylight during the equinoxes? What will the duration of sunlight be like during the Solstices? By comparing three locations; NY (mid-latitudes), the Arctic Circle (66.5o), and the equator (0o) a conclusion can be made for how latitude affects the duration of sunlight for each season.