The Solar Resource

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Capricious Suntime

[Physics in daily life] I L.J.F. (Jo) Hermans - Leiden University, e Netherlands - [email protected] - DOI: 10.1051/epn/2011202 Capricious suntime t what time of the day does the sun reach its is that the solar time will gradually deviate from the time highest point, or culmination point, when on our watch. We expect this‘eccentricity effect’ to show a its position is exactly in the South? e ans - sine-like behaviour with a period of a year. A wer to this question is not so trivial. For ere is a second, even more important complication. It is one thing, it depends on our location within our time due to the fact that the rotational axis of the earth is not zone. For Berlin, which is near the Eastern end of the perpendicular to the ecliptic, but is tilted by about 23.5 Central European time zone, it may happen around degrees. is is, aer all, the cause of our seasons. To noon, whereas in Paris it may be close to 1 p.m. (we understand this ‘tilt effect’ we must realise that what mat - ignore the daylight saving ters for the deviation in time time which adds an extra is the variation of the sun’s hour in the summer). horizontal motion against But even for a fixed loca - the stellar background tion, the time at which the during the year. In mid- sun reaches its culmination summer and mid-winter, point varies throughout the when the sun reaches its year in a surprising way. -

Solar Engineering Basics

Solar Energy Fundamentals Course No: M04-018 Credit: 4 PDH Harlan H. Bengtson, PhD, P.E. Continuing Education and Development, Inc. 22 Stonewall Court Woodcliff Lake, NJ 07677 P: (877) 322-5800 [email protected] Solar Energy Fundamentals Harlan H. Bengtson, PhD, P.E. COURSE CONTENT 1. Introduction Solar energy travels from the sun to the earth in the form of electromagnetic radiation. In this course properties of electromagnetic radiation will be discussed and basic calculations for electromagnetic radiation will be described. Several solar position parameters will be discussed along with means of calculating values for them. The major methods by which solar radiation is converted into other useable forms of energy will be discussed briefly. Extraterrestrial solar radiation (that striking the earth’s outer atmosphere) will be discussed and means of estimating its value at a given location and time will be presented. Finally there will be a presentation of how to obtain values for the average monthly rate of solar radiation striking the surface of a typical solar collector, at a specified location in the United States for a given month. Numerous examples are included to illustrate the calculations and data retrieval methods presented. Image Credit: NOAA, Earth System Research Laboratory 1 • Be able to calculate wavelength if given frequency for specified electromagnetic radiation. • Be able to calculate frequency if given wavelength for specified electromagnetic radiation. • Know the meaning of absorbance, reflectance and transmittance as applied to a surface receiving electromagnetic radiation and be able to make calculations with those parameters. • Be able to obtain or calculate values for solar declination, solar hour angle, solar altitude angle, sunrise angle, and sunset angle. -

Chapter Outline Thinking Ahead 4 EARTH, MOON, AND

Chapter 4 Earth, Moon, and Sky 103 4 EARTH, MOON, AND SKY Figure 4.1 Southern Summer. As captured with a fish-eye lens aboard the Atlantis Space Shuttle on December 9, 1993, Earth hangs above the Hubble Space Telescope as it is repaired. The reddish continent is Australia, its size and shape distorted by the special lens. Because the seasons in the Southern Hemisphere are opposite those in the Northern Hemisphere, it is summer in Australia on this December day. (credit: modification of work by NASA) Chapter Outline 4.1 Earth and Sky 4.2 The Seasons 4.3 Keeping Time 4.4 The Calendar 4.5 Phases and Motions of the Moon 4.6 Ocean Tides and the Moon 4.7 Eclipses of the Sun and Moon Thinking Ahead If Earth’s orbit is nearly a perfect circle (as we saw in earlier chapters), why is it hotter in summer and colder in winter in many places around the globe? And why are the seasons in Australia or Peru the opposite of those in the United States or Europe? The story is told that Galileo, as he left the Hall of the Inquisition following his retraction of the doctrine that Earth rotates and revolves about the Sun, said under his breath, “But nevertheless it moves.” Historians are not sure whether the story is true, but certainly Galileo knew that Earth was in motion, whatever church authorities said. It is the motions of Earth that produce the seasons and give us our measures of time and date. The Moon’s motions around us provide the concept of the month and the cycle of lunar phases. -

Sidereal Time Distribution in Large-Scale of Orbits by Usingastronomical Algorithm Method

International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) ISSN (Online): 2319-7064 Index Copernicus Value (2013): 6.14 | Impact Factor (2013): 4.438 Sidereal Time Distribution in Large-Scale of Orbits by usingAstronomical Algorithm Method Kutaiba Sabah Nimma 1UniversitiTenagaNasional,Electrical Engineering Department, Selangor, Malaysia Abstract: Sidereal Time literally means star time. The time we are used to using in our everyday lives is Solar Time.Astronomy, time based upon the rotation of the earth with respect to the distant stars, the sidereal day being the unit of measurement.Traditionally, the sidereal day is described as the time it takes for the Earth to complete one rotation relative to the stars, and help astronomers to keep them telescops directions on a given star in a night sky. In other words, earth’s rate of rotation determine according to fixed stars which is controlling the time scale of sidereal time. Many reserachers are concerned about how long the earth takes to spin based on fixed stars since the earth does not actually spin around 360 degrees in one solar day.Furthermore, the computations of the sidereal time needs to take a long time to calculate the number of the Julian centuries. This paper shows a new method of calculating the Sidereal Time, which is very important to determine the stars location at any given time. In addition, this method provdes high accuracy results with short time of calculation. Keywords: Sidereal time; Orbit allocation;Geostationary Orbit;SolarDays;Sidereal Day 1. Introduction (the upper meridian) in the sky[6]. Solar time is what the time we all use where a day is defined as 24 hours, which is The word "sidereal" comes from the Latin word sider, the average time that it takes for the sun to return to its meaning star. -

Sidereal Time 1 Sidereal Time

Sidereal time 1 Sidereal time Sidereal time (pronounced /saɪˈdɪəri.əl/) is a time-keeping system astronomers use to keep track of the direction to point their telescopes to view a given star in the night sky. Just as the Sun and Moon appear to rise in the east and set in the west, so do the stars. A sidereal day is approximately 23 hours, 56 minutes, 4.091 seconds (23.93447 hours or 0.99726957 SI days), corresponding to the time it takes for the Earth to complete one rotation relative to the vernal equinox. The vernal equinox itself precesses very slowly in a westward direction relative to the fixed stars, completing one revolution every 26,000 years approximately. As a consequence, the misnamed sidereal day, as "sidereal" is derived from the Latin sidus meaning "star", is some 0.008 seconds shorter than the earth's period of rotation relative to the fixed stars. The longer true sidereal period is called a stellar day by the International Earth Rotation and Reference Systems Service (IERS). It is also referred to as the sidereal period of rotation. The direction from the Earth to the Sun is constantly changing (because the Earth revolves around the Sun over the course of a year), but the directions from the Earth to the distant stars do not change nearly as much. Therefore the cycle of the apparent motion of the stars around the Earth has a period that is not quite the same as the 24-hour average length of the solar day. Maps of the stars in the night sky usually make use of declination and right ascension as coordinates. -

Equation of Time — Problem in Astronomy M

This paper was awarded in the II International Competition (1993/94) "First Step to Nobel Prize in Physics" and published in the competition proceedings (Acta Phys. Pol. A 88 Supplement, S-49 (1995)). The paper is reproduced here due to kind agreement of the Editorial Board of "Acta Physica Polonica A". EQUATION OF TIME | PROBLEM IN ASTRONOMY M. Muller¨ Gymnasium M¨unchenstein, Grellingerstrasse 5, 4142 M¨unchenstein, Switzerland Abstract The apparent solar motion is not uniform and the length of a solar day is not constant throughout a year. The difference between apparent solar time and mean (regular) solar time is called the equation of time. Two well-known features of our solar system lie at the basis of the periodic irregularities in the solar motion. The angular velocity of the earth relative to the sun varies periodically in the course of a year. The plane of the orbit of the earth is inclined with respect to the equatorial plane. Therefore, the angular velocity of the relative motion has to be projected from the ecliptic onto the equatorial plane before incorporating it into the measurement of time. The math- ematical expression of the projection factor for ecliptic angular velocities yields an oscillating function with two periods per year. The difference between the extreme values of the equation of time is about half an hour. The response of the equation of time to a variation of its key parameters is analyzed. In order to visualize factors contributing to the equation of time a model has been constructed which accounts for the elliptical orbit of the earth, the periodically changing angular velocity, and the inclined axis of the earth. -

3.- the Geographic Position of a Celestial Body

Chapter 3 Copyright © 1997-2004 Henning Umland All Rights Reserved Geographic Position and Time Geographic terms In celestial navigation, the earth is regarded as a sphere. Although this is an approximation, the geometry of the sphere is applied successfully, and the errors caused by the flattening of the earth are usually negligible (chapter 9). A circle on the surface of the earth whose plane passes through the center of the earth is called a great circle . Thus, a great circle has the greatest possible diameter of all circles on the surface of the earth. Any circle on the surface of the earth whose plane does not pass through the earth's center is called a small circle . The equator is the only great circle whose plane is perpendicular to the polar axis , the axis of rotation. Further, the equator is the only parallel of latitude being a great circle. Any other parallel of latitude is a small circle whose plane is parallel to the plane of the equator. A meridian is a great circle going through the geographic poles , the points where the polar axis intersects the earth's surface. The upper branch of a meridian is the half from pole to pole passing through a given point, e. g., the observer's position. The lower branch is the opposite half. The Greenwich meridian , the meridian passing through the center of the transit instrument at the Royal Greenwich Observatory , was adopted as the prime meridian at the International Meridian Conference in 1884. Its upper branch is the reference for measuring longitudes (0°...+180° east and 0°...–180° west), its lower branch (180°) is the basis for the International Dateline (Fig. -

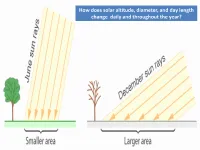

How Does Solar Altitude, Diameter, and Day Length Change Daily and Throughout the Year?

How does solar altitude, diameter, and day length change daily and throughout the year? Let’s prove distance doesn’t matter in seasons by investigating SOLAR ALTITUDE, DAY LENGTH and SOLAR DISTANCE… Would the sun have the same appearance if you observed it from other planets? Why do we see the sun at different altitudes throughout the day? We use the altitude of the sun at a time called solar “noon” because of daily solar altitude changes from the horizon at sunrise and sunset to it’s maximum daily altitude at noon. If you think solar noon is at 12:00:00, you’re mistaken! Solar “noon” doesn’t usually happen at clock-noon at your longitude for lots of reasons! SOLAR INTENSITY and ALTITUDE - Maybe a FLASHLIGHT will help us see this relationship! Draw the beam shape for 3 solar altitudes in your notebooks! How would knowing solar altitude daily and seasonally help make solar panels (collectors)work best? Where would the sun have to be located to capture the maximum amount of sunlight energy? Draw the sun in the right position to maximize the light it receives on panel For the northern hemisphere, in which general direction would they be pointed? For the southern hemisphere, in which direction would they be pointed? SOLAR PANELS at different ANGLES ON GROUND How do shadows show us solar altitude? You used a FLASHLIGHT and MODELING CLAY to show you how SOLAR INTENSITY, ALTITUDE, and SHADOW LENGTH are related! Using at least three solar altitudes and locations, draw your conceptual model of this relationship in your notebooks… Label: Sun compass direction Shadow compass direction Solar altitude Shadow length (long/short) Sun intensity What did the lab show us about how SOLAR ALTITUDE, DIAMETER, & DAY LENGTH relate to each other? YOUR GRAPHS are PROBABLY the easiest way to SEE the RELATIONSHIPS. -

2 Coordinate Systems

2 Coordinate systems In order to find something one needs a system of coordinates. For determining the positions of the stars and planets where the distance to the object often is unknown it usually suffices to use two coordinates. On the other hand, since the Earth rotates around it’s own axis as well as around the Sun the positions of stars and planets is continually changing, and the measurment of when an object is in a certain place is as important as deciding where it is. Our first task is to decide on a coordinate system and the position of 1. The origin. E.g. one’s own location, the center of the Earth, the, the center of the Solar System, the Galaxy, etc. 2. The fundamental plan (x−y plane). This is often a plane of some physical significance such as the horizon, the equator, or the ecliptic. 3. Decide on the direction of the positive x-axis, also known as the “reference direction”. 4. And, finally, on a convention of signs of the y− and z− axes, i.e whether to use a left-handed or right-handed coordinate system. For example Eratosthenes of Cyrene (c. 276 BC c. 195 BC) was a Greek mathematician, elegiac poet, athlete, geographer, astronomer, and music theo- rist who invented a system of latitude and longitude. (According to Wikipedia he was also the first person to use the word geography and invented the disci- pline of geography as we understand it.). The origin of this coordinate system was the center of the Earth and the fundamental plane was the equator, which location Eratosthenes calculated relative to the parts of the Earth known to him. -

Celestial Coordinate Systems

Celestial Coordinate Systems Craig Lage Department of Physics, New York University, [email protected] January 6, 2014 1 Introduction This document reviews briefly some of the key ideas that you will need to understand in order to identify and locate objects in the sky. It is intended to serve as a reference document. 2 Angular Basics When we view objects in the sky, distance is difficult to determine, and generally we can only indicate their direction. For this reason, angles are critical in astronomy, and we use angular measures to locate objects and define the distance between objects. Angles are measured in a number of different ways in astronomy, and you need to become familiar with the different notations and comfortable converting between them. A basic angle is shown in Figure 1. θ Figure 1: A basic angle, θ. We review some angle basics. We normally use two primary measures of angles, degrees and radians. In astronomy, we also sometimes use time as a measure of angles, as we will discuss later. A radian is a dimensionless measure equal to the length of the circular arc enclosed by the angle divided by the radius of the circle. A full circle is thus equal to 2π radians. A degree is an arbitrary measure, where a full circle is defined to be equal to 360◦. When using degrees, we also have two different conventions, to divide one degree into decimal degrees, or alternatively to divide it into 60 minutes, each of which is divided into 60 seconds. These are also referred to as minutes of arc or seconds of arc so as not to confuse them with minutes of time and seconds of time. -

Lecture 6: Where Is the Sun?

4.430 Daylighting Massachusetts Institute of Technology Christoph Reinhart Department of Architecture 4.430 Where is the sun? Building Technology Program Goals for This Week Where is the sun? Designing Static Shading Systems MIT 4.430 Daylighting, Instructor C Reinhart 1 1 MISC Meeting on group projects Reduce HDR image size via pfilt –x 800 –y 550 filne_name_large.pic > filename_small>.pic Note: pfilt is a Radiance program. You can find further info on pfilt by googeling: “pfilt Radiance” MIT 4.430 Daylighting, Instructor C Reinhart 2 2 Daylight Factor Hand Calculation Mean Daylight Factor according to Lynes Reinhart & LoVerso, Lighting Research & Technology (2010) Move into the building, design the facade openings, room dimensions and depth of the daylit area. Determine the required glazing area using the Lynes formula. A glazing = required glazing area A total = overall interior surface area (not floor area!) R mean = area-weighted mean surface reflectance vis = visual transmittance of glazing units = sun angle 3 ‘Validation’ of Daylight Factor Formula Reinhart & LoVerso, Lighting Research & Technology (2010) Graph of mean daylighting factor according to Lynes formula v. Radiance removed due to copyright restrictions. Source: Figure 5 in Reinhart, C. F., and V. R. M. LoVerso. "A Rules of Thumb Based Design Sequence for Diffuse Daylight." Lighting Research and Technology 42, no. 1 (2010): 7-32. Comparison to Radiance simulations for 2304 spaces. Quality control for simulations. LEED 2.2 Glazing Factor Formula Graph of mean daylighting factor according to LEED 2.2 v. Radiance removed due to copyright restrictions. Source: Figure 11 in Reinhart, C. F., and V. -

Solar Photovoltaic (PV) Site Assessment

Solar Photovoltaic (PV) Site Assessment Item Type text; Book Authors Franklin, Ed Publisher College of Agriculture, University of Arizona (Tucson, AZ) Download date 29/09/2021 11:10:49 Item License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/625447 az1697 August 2017 Solar Photovoltaic (PV) Site Assessment Dr. Ed Franklin Introduction An important consideration when installing a solar photovoltaic (PV) array for residential, commercial, or agricultural operations is determining the suitability of the site. A roof-top location for a residential application may have fewer options due to limited space (roof size), type of roofing material (such as a sloped shingle, or a flat roof), the orientation (south, east, or west), and roof-mounted structures such as vent pipe, chimney, heating & cooling units. A location with open space may utilize a ground-mount system or pole-mount system. Determining the physical location of a solar PV array is a critical step to optimize energy output performance of the system. The ideal location is where solar modules are exposed to full sunshine from sun up to sun down without worry about shade cast on the modules from trees, power poles, guide wires, vent pipes, or nearby buildings, or the changing location of the sun. In the Northern Hemisphere, solar PV arrays are oriented to the south toward the Equator. Over the course of a calendar year, the sun’s altitude (height) in the sky changes. For example, during the month of June, the sun reaches its highest point in the sky on June 21 at 12:00 noon (summer solstice), and the sun Figure 1.