Local Sidereal Time (LST) = Greenwich Sidereal Time (GST) +

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ast 443 / Phy 517

AST 443 / PHY 517 Astronomical Observing Techniques Prof. F.M. Walter I. The Basics The 3 basic measurements: • WHERE something is • WHEN something happened • HOW BRIGHT something is Since this is science, let’s be quantitative! Where • Positions: – 2-dimensional projections on celestial sphere (q,f) • q,f are angular measures: radians, or degrees, minutes, arcsec – 3-dimensional position in space (x,y,z) or (q, f, r). • (x,y,z) are linear positions within a right-handed rectilinear coordinate system. • R is a distance (spherical coordinates) • Galactic positions are sometimes presented in cylindrical coordinates, of galactocentric radius, height above the galactic plane, and azimuth. Angles There are • 360 degrees (o) in a circle • 60 minutes of arc (‘) in a degree (arcmin) • 60 seconds of arc (“) in an arcmin There are • 24 hours (h) along the equator • 60 minutes of time (m) per hour • 60 seconds of time (s) per minute • 1 second of time = 15”/cos(latitude) Coordinate Systems "What good are Mercator's North Poles and Equators Tropics, Zones, and Meridian Lines?" So the Bellman would cry, and the crew would reply "They are merely conventional signs" L. Carroll -- The Hunting of the Snark • Equatorial (celestial): based on terrestrial longitude & latitude • Ecliptic: based on the Earth’s orbit • Altitude-Azimuth (alt-az): local • Galactic: based on MilKy Way • Supergalactic: based on supergalactic plane Reference points Celestial coordinates (Right Ascension α, Declination δ) • δ = 0: projection oF terrestrial equator • (α, δ) = (0,0): -

Solar Engineering Basics

Solar Energy Fundamentals Course No: M04-018 Credit: 4 PDH Harlan H. Bengtson, PhD, P.E. Continuing Education and Development, Inc. 22 Stonewall Court Woodcliff Lake, NJ 07677 P: (877) 322-5800 [email protected] Solar Energy Fundamentals Harlan H. Bengtson, PhD, P.E. COURSE CONTENT 1. Introduction Solar energy travels from the sun to the earth in the form of electromagnetic radiation. In this course properties of electromagnetic radiation will be discussed and basic calculations for electromagnetic radiation will be described. Several solar position parameters will be discussed along with means of calculating values for them. The major methods by which solar radiation is converted into other useable forms of energy will be discussed briefly. Extraterrestrial solar radiation (that striking the earth’s outer atmosphere) will be discussed and means of estimating its value at a given location and time will be presented. Finally there will be a presentation of how to obtain values for the average monthly rate of solar radiation striking the surface of a typical solar collector, at a specified location in the United States for a given month. Numerous examples are included to illustrate the calculations and data retrieval methods presented. Image Credit: NOAA, Earth System Research Laboratory 1 • Be able to calculate wavelength if given frequency for specified electromagnetic radiation. • Be able to calculate frequency if given wavelength for specified electromagnetic radiation. • Know the meaning of absorbance, reflectance and transmittance as applied to a surface receiving electromagnetic radiation and be able to make calculations with those parameters. • Be able to obtain or calculate values for solar declination, solar hour angle, solar altitude angle, sunrise angle, and sunset angle. -

The Determination of Longitude in Landsurveying.” by ROBERTHENRY BURNSIDE DOWSES, Assoc

316 DOWNES ON LONGITUDE IN LAXD SUIWETISG. [Selected (Paper No. 3027.) The Determination of Longitude in LandSurveying.” By ROBERTHENRY BURNSIDE DOWSES, Assoc. M. Inst. C.E. THISPaper is presented as a sequel tothe Author’s former communication on “Practical Astronomy as applied inLand Surveying.”’ It is not generally possible for a surveyor in the field to obtain accurate determinationsof longitude unless furnished with more powerful instruments than is usually the case, except in geodetic camps; still, by the methods here given, he may with care obtain results near the truth, the error being only instrumental. There are threesuch methods for obtaining longitudes. Method 1. By Telrgrcrph or by Chronometer.-In either case it is necessary to obtain the truemean time of the place with accuracy, by means of an observation of the sun or z star; then, if fitted with a field telegraph connected with some knownlongitude, the true mean time of that place is obtained by telegraph and carefully compared withthe observed true mean time atthe observer’s place, andthe difference between thesetimes is the difference of longitude required. With a reliable chronometer set totrue Greenwich mean time, or that of anyother known observatory, the difference between the times of the place and the time of the chronometer must be noted, when the difference of longitude is directly deduced. Thisis the simplest method where a camp is furnisl~ed with eitherof these appliances, which is comparatively rarely the case. Method 2. By Lunar Distances.-This observation is one requiring great care, accurately adjusted instruments, and some littleskill to obtain good results;and the calculations are somewhat laborious. -

Sidereal Time Distribution in Large-Scale of Orbits by Usingastronomical Algorithm Method

International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) ISSN (Online): 2319-7064 Index Copernicus Value (2013): 6.14 | Impact Factor (2013): 4.438 Sidereal Time Distribution in Large-Scale of Orbits by usingAstronomical Algorithm Method Kutaiba Sabah Nimma 1UniversitiTenagaNasional,Electrical Engineering Department, Selangor, Malaysia Abstract: Sidereal Time literally means star time. The time we are used to using in our everyday lives is Solar Time.Astronomy, time based upon the rotation of the earth with respect to the distant stars, the sidereal day being the unit of measurement.Traditionally, the sidereal day is described as the time it takes for the Earth to complete one rotation relative to the stars, and help astronomers to keep them telescops directions on a given star in a night sky. In other words, earth’s rate of rotation determine according to fixed stars which is controlling the time scale of sidereal time. Many reserachers are concerned about how long the earth takes to spin based on fixed stars since the earth does not actually spin around 360 degrees in one solar day.Furthermore, the computations of the sidereal time needs to take a long time to calculate the number of the Julian centuries. This paper shows a new method of calculating the Sidereal Time, which is very important to determine the stars location at any given time. In addition, this method provdes high accuracy results with short time of calculation. Keywords: Sidereal time; Orbit allocation;Geostationary Orbit;SolarDays;Sidereal Day 1. Introduction (the upper meridian) in the sky[6]. Solar time is what the time we all use where a day is defined as 24 hours, which is The word "sidereal" comes from the Latin word sider, the average time that it takes for the sun to return to its meaning star. -

Sidereal Time 1 Sidereal Time

Sidereal time 1 Sidereal time Sidereal time (pronounced /saɪˈdɪəri.əl/) is a time-keeping system astronomers use to keep track of the direction to point their telescopes to view a given star in the night sky. Just as the Sun and Moon appear to rise in the east and set in the west, so do the stars. A sidereal day is approximately 23 hours, 56 minutes, 4.091 seconds (23.93447 hours or 0.99726957 SI days), corresponding to the time it takes for the Earth to complete one rotation relative to the vernal equinox. The vernal equinox itself precesses very slowly in a westward direction relative to the fixed stars, completing one revolution every 26,000 years approximately. As a consequence, the misnamed sidereal day, as "sidereal" is derived from the Latin sidus meaning "star", is some 0.008 seconds shorter than the earth's period of rotation relative to the fixed stars. The longer true sidereal period is called a stellar day by the International Earth Rotation and Reference Systems Service (IERS). It is also referred to as the sidereal period of rotation. The direction from the Earth to the Sun is constantly changing (because the Earth revolves around the Sun over the course of a year), but the directions from the Earth to the distant stars do not change nearly as much. Therefore the cycle of the apparent motion of the stars around the Earth has a period that is not quite the same as the 24-hour average length of the solar day. Maps of the stars in the night sky usually make use of declination and right ascension as coordinates. -

3.- the Geographic Position of a Celestial Body

Chapter 3 Copyright © 1997-2004 Henning Umland All Rights Reserved Geographic Position and Time Geographic terms In celestial navigation, the earth is regarded as a sphere. Although this is an approximation, the geometry of the sphere is applied successfully, and the errors caused by the flattening of the earth are usually negligible (chapter 9). A circle on the surface of the earth whose plane passes through the center of the earth is called a great circle . Thus, a great circle has the greatest possible diameter of all circles on the surface of the earth. Any circle on the surface of the earth whose plane does not pass through the earth's center is called a small circle . The equator is the only great circle whose plane is perpendicular to the polar axis , the axis of rotation. Further, the equator is the only parallel of latitude being a great circle. Any other parallel of latitude is a small circle whose plane is parallel to the plane of the equator. A meridian is a great circle going through the geographic poles , the points where the polar axis intersects the earth's surface. The upper branch of a meridian is the half from pole to pole passing through a given point, e. g., the observer's position. The lower branch is the opposite half. The Greenwich meridian , the meridian passing through the center of the transit instrument at the Royal Greenwich Observatory , was adopted as the prime meridian at the International Meridian Conference in 1884. Its upper branch is the reference for measuring longitudes (0°...+180° east and 0°...–180° west), its lower branch (180°) is the basis for the International Dateline (Fig. -

A Short Guide to Celestial Navigation5.16 MB

A Short Guide to elestial Na1igation Copyright A 1997 2011 (enning -mland Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the G.2 Free Documentation -icense, 3ersion 1.3 or any later version published by the Free 0oftware Foundation% with no ,nvariant 0ections, no Front Cover 1eIts and no Back Cover 1eIts. A copy of the license is included in the section entitled "G.2 Free Documentation -icense". ,evised October 1 st , 2011 First Published May 20 th , 1997 .ndeB 1reface Chapter 1he Basics of Celestial ,aEigation Chapter 2 Altitude Measurement Chapter 3 )eographic .osition and 1ime Chapter 4 Finding One's .osition 0ight Reduction) Chapter 5 Finding the .osition of an Advancing 2essel Determination of Latitude and Longitude, Direct Calculation of Chapter 6 .osition Chapter 7 Finding 1ime and Longitude by Lunar Distances Chapter 8 Rise, 0et, 1wilight Chapter 9 )eodetic Aspects of Celestial ,aEigation Chapter 0 0pherical 1rigonometry Chapter 1he ,aEigational 1riangle Chapter 12 )eneral Formulas for ,aEigation Chapter 13 Charts and .lotting 0heets Chapter 14 Magnetic Declination Chapter 15 Ephemerides of the 0un Chapter 16 ,aEigational Errors Chapter 17 1he Marine Chronometer AppendiB -02 ,ree Documentation /icense Much is due to those who first bro-e the way to -now.edge, and .eft on.y to their successors the tas- of smoothing it Samue. Johnson Prefa e Why should anybody still practice celestial naRigation in the era of electronics and 18S? 7ne might as Sell ask Shy some photographers still develop black-and-Shite photos in their darkroom instead of using a digital camera. -

2 Coordinate Systems

2 Coordinate systems In order to find something one needs a system of coordinates. For determining the positions of the stars and planets where the distance to the object often is unknown it usually suffices to use two coordinates. On the other hand, since the Earth rotates around it’s own axis as well as around the Sun the positions of stars and planets is continually changing, and the measurment of when an object is in a certain place is as important as deciding where it is. Our first task is to decide on a coordinate system and the position of 1. The origin. E.g. one’s own location, the center of the Earth, the, the center of the Solar System, the Galaxy, etc. 2. The fundamental plan (x−y plane). This is often a plane of some physical significance such as the horizon, the equator, or the ecliptic. 3. Decide on the direction of the positive x-axis, also known as the “reference direction”. 4. And, finally, on a convention of signs of the y− and z− axes, i.e whether to use a left-handed or right-handed coordinate system. For example Eratosthenes of Cyrene (c. 276 BC c. 195 BC) was a Greek mathematician, elegiac poet, athlete, geographer, astronomer, and music theo- rist who invented a system of latitude and longitude. (According to Wikipedia he was also the first person to use the word geography and invented the disci- pline of geography as we understand it.). The origin of this coordinate system was the center of the Earth and the fundamental plane was the equator, which location Eratosthenes calculated relative to the parts of the Earth known to him. -

Celestial Coordinate Systems

Celestial Coordinate Systems Craig Lage Department of Physics, New York University, [email protected] January 6, 2014 1 Introduction This document reviews briefly some of the key ideas that you will need to understand in order to identify and locate objects in the sky. It is intended to serve as a reference document. 2 Angular Basics When we view objects in the sky, distance is difficult to determine, and generally we can only indicate their direction. For this reason, angles are critical in astronomy, and we use angular measures to locate objects and define the distance between objects. Angles are measured in a number of different ways in astronomy, and you need to become familiar with the different notations and comfortable converting between them. A basic angle is shown in Figure 1. θ Figure 1: A basic angle, θ. We review some angle basics. We normally use two primary measures of angles, degrees and radians. In astronomy, we also sometimes use time as a measure of angles, as we will discuss later. A radian is a dimensionless measure equal to the length of the circular arc enclosed by the angle divided by the radius of the circle. A full circle is thus equal to 2π radians. A degree is an arbitrary measure, where a full circle is defined to be equal to 360◦. When using degrees, we also have two different conventions, to divide one degree into decimal degrees, or alternatively to divide it into 60 minutes, each of which is divided into 60 seconds. These are also referred to as minutes of arc or seconds of arc so as not to confuse them with minutes of time and seconds of time. -

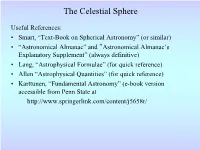

The Celestial Sphere

The Celestial Sphere Useful References: • Smart, “Text-Book on Spherical Astronomy” (or similar) • “Astronomical Almanac” and “Astronomical Almanac’s Explanatory Supplement” (always definitive) • Lang, “Astrophysical Formulae” (for quick reference) • Allen “Astrophysical Quantities” (for quick reference) • Karttunen, “Fundamental Astronomy” (e-book version accessible from Penn State at http://www.springerlink.com/content/j5658r/ Numbers to Keep in Mind • 4 π (180 / π)2 = 41,253 deg2 on the sky • ~ 23.5° = obliquity of the ecliptic • 17h 45m, -29° = coordinates of Galactic Center • 12h 51m, +27° = coordinates of North Galactic Pole • 18h, +66°33’ = coordinates of North Ecliptic Pole Spherical Astronomy Geocentrically speaking, the Earth sits inside a celestial sphere containing fixed stars. We are therefore driven towards equations based on spherical coordinates. Rules for Spherical Astronomy • The shortest distance between two points on a sphere is a great circle. • The length of a (great circle) arc is proportional to the angle created by the two radial vectors defining the points. • The great-circle arc length between two points on a sphere is given by cos a = (cos b cos c) + (sin b sin c cos A) where the small letters are angles, and the capital letters are the arcs. (This is the fundamental equation of spherical trigonometry.) • Two other spherical triangle relations which can be derived from the fundamental equation are sin A sinB = and sin a cos B = cos b sin c – sin b cos c cos A sina sinb € Proof of Fundamental Equation • O is -

The Solar Resource

CHAPTER 7 THE SOLAR RESOURCE To design and analyze solar systems, we need to know how much sunlight is available. A fairly straightforward, though complicated-looking, set of equations can be used to predict where the sun is in the sky at any time of day for any location on earth, as well as the solar intensity (or insolation: incident solar Radiation) on a clear day. To determine average daily insolation under the com- bination of clear and cloudy conditions that exist at any site we need to start with long-term measurements of sunlight hitting a horizontal surface. Another set of equations can then be used to estimate the insolation on collector surfaces that are not flat on the ground. 7.1 THE SOLAR SPECTRUM The source of insolation is, of course, the sun—that gigantic, 1.4 million kilo- meter diameter, thermonuclear furnace fusing hydrogen atoms into helium. The resulting loss of mass is converted into about 3.8 × 1020 MW of electromagnetic energy that radiates outward from the surface into space. Every object emits radiant energy in an amount that is a function of its tem- perature. The usual way to describe how much radiation an object emits is to compare it to a theoretical abstraction called a blackbody. A blackbody is defined to be a perfect emitter as well as a perfect absorber. As a perfect emitter, it radiates more energy per unit of surface area than any real object at the same temperature. As a perfect absorber, it absorbs all radiation that impinges upon it; that is, none Renewable and Efficient Electric Power Systems. -

Using the SFA Star Charts and Understanding the Equatorial Coordinate System

Using the SFA Star Charts and Understanding the Equatorial Coordinate System SFA Star Charts created by Dan Bruton of Stephen F. Austin State University Notes written by Don Carona of Texas A&M University Last Updated: August 17, 2020 The SFA Star Charts are four separate charts. Chart 1 is for the north celestial region and chart 4 is for the south celestial region. These notes refer to the equatorial charts, which are charts 2 & 3 combined to form one long chart. The star charts are based on the Equatorial Coordinate System, which consists of right ascension (RA), declination (DEC) and hour angle (HA). From the northern hemisphere, the equatorial charts can be used when facing south, east or west. At the bottom of the chart, you’ll notice a series of twenty-four numbers followed by the letter “h”, representing “hours”. These hour marks are right ascension (RA), which is the equivalent of celestial longitude. The same point on the 360 degree celestial sphere passes overhead every 24 hours, making each hour of right ascension equal to 1/24th of a circle, or 15 degrees. Each degree of sky, therefore, moves past a stationary point in four minutes. Each hour of right ascension moves past a stationary point in one hour. Every tick mark between the hour marks on the equatorial charts is equal to 5 minutes. Right ascension is noted in ( h ) hours, ( m ) minutes, and ( s ) seconds. The bright star, Antares, in the constellation Scorpius. is located at RA 16h 29m 30s. At the left and right edges of the chart, you will find numbers marked in degrees (°) and being either positive (+) or negative(-).