Using the SFA Star Charts and Understanding the Equatorial Coordinate System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Commission 27 of the Iau Information Bulletin

COMMISSION 27 OF THE I.A.U. INFORMATION BULLETIN ON VARIABLE STARS Nos. 2401 - 2500 1983 September - 1984 March EDITORS: B. SZEIDL AND L. SZABADOS, KONKOLY OBSERVATORY 1525 BUDAPEST, Box 67, HUNGARY HU ISSN 0374-0676 CONTENTS 2401 A POSSIBLE CATACLYSMIC VARIABLE IN CANCER Masaaki Huruhata 20 September 1983 2402 A NEW RR-TYPE VARIABLE IN LEO Masaaki Huruhata 20 September 1983 2403 ON THE DELTA SCUTI STAR BD +43d1894 A. Yamasaki, A. Okazaki, M. Kitamura 23 September 1983 2404 IQ Vel: IMPROVED LIGHT-CURVE PARAMETERS L. Kohoutek 26 September 1983 2405 FLARE ACTIVITY OF EPSILON AURIGAE? I.-S. Nha, S.J. Lee 28 September 1983 2406 PHOTOELECTRIC OBSERVATIONS OF 20 CVn Y.W. Chun, Y.S. Lee, I.-S. Nha 30 September 1983 2407 MINIMUM TIMES OF THE ECLIPSING VARIABLES AH Cep AND IU Aur Pavel Mayer, J. Tremko 4 October 1983 2408 PHOTOELECTRIC OBSERVATIONS OF THE FLARE STAR EV Lac IN 1980 G. Asteriadis, S. Avgoloupis, L.N. Mavridis, P. Varvoglis 6 October 1983 2409 HD 37824: A NEW VARIABLE STAR Douglas S. Hall, G.W. Henry, H. Louth, T.R. Renner 10 October 1983 2410 ON THE PERIOD OF BW VULPECULAE E. Szuszkiewicz, S. Ratajczyk 12 October 1983 2411 THE UNIQUE DOUBLE-MODE CEPHEID CO Aur E. Antonello, L. Mantegazza 14 October 1983 2412 FLARE STARS IN TAURUS A.S. Hojaev 14 October 1983 2413 BVRI PHOTOMETRY OF THE ECLIPSING BINARY QX Cas Thomas J. Moffett, T.G. Barnes, III 17 October 1983 2414 THE ABSOLUTE MAGNITUDE OF AZ CANCRI William P. Bidelman, D. Hoffleit 17 October 1983 2415 NEW DATA ABOUT THE APSIDAL MOTION IN THE SYSTEM OF RU MONOCEROTIS D.Ya. -

The Dunhuang Chinese Sky: a Comprehensive Study of the Oldest Known Star Atlas

25/02/09JAHH/v4 1 THE DUNHUANG CHINESE SKY: A COMPREHENSIVE STUDY OF THE OLDEST KNOWN STAR ATLAS JEAN-MARC BONNET-BIDAUD Commissariat à l’Energie Atomique ,Centre de Saclay, F-91191 Gif-sur-Yvette, France E-mail: [email protected] FRANÇOISE PRADERIE Observatoire de Paris, 61 Avenue de l’Observatoire, F- 75014 Paris, France E-mail: [email protected] and SUSAN WHITFIELD The British Library, 96 Euston Road, London NW1 2DB, UK E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: This paper presents an analysis of the star atlas included in the medieval Chinese manuscript (Or.8210/S.3326), discovered in 1907 by the archaeologist Aurel Stein at the Silk Road town of Dunhuang and now held in the British Library. Although partially studied by a few Chinese scholars, it has never been fully displayed and discussed in the Western world. This set of sky maps (12 hour angle maps in quasi-cylindrical projection and a circumpolar map in azimuthal projection), displaying the full sky visible from the Northern hemisphere, is up to now the oldest complete preserved star atlas from any civilisation. It is also the first known pictorial representation of the quasi-totality of the Chinese constellations. This paper describes the history of the physical object – a roll of thin paper drawn with ink. We analyse the stellar content of each map (1339 stars, 257 asterisms) and the texts associated with the maps. We establish the precision with which the maps are drawn (1.5 to 4° for the brightest stars) and examine the type of projections used. -

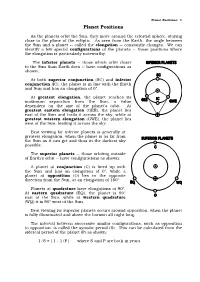

Planet Positions: 1 Planet Positions

Planet Positions: 1 Planet Positions As the planets orbit the Sun, they move around the celestial sphere, staying close to the plane of the ecliptic. As seen from the Earth, the angle between the Sun and a planet -- called the elongation -- constantly changes. We can identify a few special configurations of the planets -- those positions where the elongation is particularly noteworthy. The inferior planets -- those which orbit closer INFERIOR PLANETS to the Sun than Earth does -- have configurations as shown: SC At both superior conjunction (SC) and inferior conjunction (IC), the planet is in line with the Earth and Sun and has an elongation of 0°. At greatest elongation, the planet reaches its IC maximum separation from the Sun, a value GEE GWE dependent on the size of the planet's orbit. At greatest eastern elongation (GEE), the planet lies east of the Sun and trails it across the sky, while at greatest western elongation (GWE), the planet lies west of the Sun, leading it across the sky. Best viewing for inferior planets is generally at greatest elongation, when the planet is as far from SUPERIOR PLANETS the Sun as it can get and thus in the darkest sky possible. C The superior planets -- those orbiting outside of Earth's orbit -- have configurations as shown: A planet at conjunction (C) is lined up with the Sun and has an elongation of 0°, while a planet at opposition (O) lies in the opposite direction from the Sun, at an elongation of 180°. EQ WQ Planets at quadrature have elongations of 90°. -

Star Chart Lab

Star Chart Lab 6) a. About how many stars are in the Pleiades cluster? Star Chart Lab b. Why do you think its nick name is “The Seven Sisters”? c. Which constellation is the Pleiades cluster in? •Materials 7) Star Atlas Deluxe Edition a. Which named star is ten arc minutes from the brightest star in the constellation Gemini? •Procedure b. Is the brightest “star” in Gemini actually just one star? In this lab, you will explore the star charts of c. What type of object lies 38 arc minutes less our night sky. You might want to skim the intro- in RA, 0.6o in Dec. south from the star Pollux? duction at the front of the charts before you d. What type of object lies about 20 arc minuets begin. In the front or back of the book you’ll less in RA, 1.5o in Dec. north of Pollux? find a transparency which lays over the charts, giving you more detailed measurements. Star 8) When looking in the night sky from campus, charts use a special type of coordinates, called you certainly see fewer stars than are on these the Equatorial system. If you are not familiar maps. Many constellations are actually easier to with this system, e.g. Right Ascension (RA) and find in conditions such as on campus. Declination (Dec.), then take a minute to read a. Which stars do you think you can see in the Appendix A of this manual. Otherwise, answer constellation Lyra from campus? the questions below. b. What planetary nebula is in Lyra? c. -

Sun Tool Options

Sun Study Tools Sophomore Architecture Studio: Lighting Lecture 1: • Introduction to Daylight (part 1) • Survey of the Color Spectrum • Making Light • Controlling Light Lecture 2: • Daylight (part 2) • Design Tools to study Solar Design • Architectural Applications Lecture 3: • Light in Architecture • Lighting Design Strategies Sun Tool Options 1. Paper and Pencil 2. Build a Model 3. Use a Computer The first step to any of these options is to define…. Where is the site? 1 2 Sun Study Tools North Latitude and Longitude South Longitude Latitude Longitude Sun Study Tools North America Latitude 3 United States e ud tit La Sun Study Tools New York 72w 44n 42n Site Location The site location is specified by a latitude l and a longitude L. Latitudes and longitudes may be found in any standard atlas or almanac. Chart shows the latitudes and longitudes of some North American cities. Conventions used in expressing latitudes are: Positive = northern hemisphere Negative = southern hemisphere Conventions used in expressing longitudes are: Positive = west of prime meridian (Greenwich, United Kingdom) Latitude and Longitude of Some North American Cities Negative = east of prime meridian 4 Sun Study Tools Solar Path Suns Position The position of the sun is specified by the solar altitude and solar azimuth and is a function of site latitude, solar time, and solar declination. 5 Sun Study Tools Suns Position The rotation of the earth about its axis, as well as its revolution about the sun, produces an apparent motion of the sun with respect to any point on the altitude earth's surface. The position of the sun with respect to such a point is expressed in terms of two angles: azimuth The sun's position in terms of solar altitude (a ) and azimuth (a ) solar azimuth, which is the t s with respect to the cardinal points of the compass. -

Basic Principles of Celestial Navigation James A

Basic principles of celestial navigation James A. Van Allena) Department of Physics and Astronomy, The University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa 52242 ͑Received 16 January 2004; accepted 10 June 2004͒ Celestial navigation is a technique for determining one’s geographic position by the observation of identified stars, identified planets, the Sun, and the Moon. This subject has a multitude of refinements which, although valuable to a professional navigator, tend to obscure the basic principles. I describe these principles, give an analytical solution of the classical two-star-sight problem without any dependence on prior knowledge of position, and include several examples. Some approximations and simplifications are made in the interest of clarity. © 2004 American Association of Physics Teachers. ͓DOI: 10.1119/1.1778391͔ I. INTRODUCTION longitude ⌳ is between 0° and 360°, although often it is convenient to take the longitude westward of the prime me- Celestial navigation is a technique for determining one’s ridian to be between 0° and Ϫ180°. The longitude of P also geographic position by the observation of identified stars, can be specified by the plane angle in the equatorial plane identified planets, the Sun, and the Moon. Its basic principles whose vertex is at O with one radial line through the point at are a combination of rudimentary astronomical knowledge 1–3 which the meridian through P intersects the equatorial plane and spherical trigonometry. and the other radial line through the point G at which the Anyone who has been on a ship that is remote from any prime meridian intersects the equatorial plane ͑see Fig. -

Celestial Navigation (Fall) NAME GROUP

SIERRA COLLEGE OBSERVATIONAL ASTRONOMY LABORATORY EXERCISE Lab N03: Celestial Navigation (Fall) NAME GROUP OBJECTIVE: Learn about the Celestial Coordinate System. Learn about stellar designations. Learn about deep sky object designations. INTRODUCTION: The Horizon Coordinate System is simple, but flawed, because the altitude and azimuth measures of stars change as the sky rotates. Astronomers have developed an improved scheme called the Celestial Coordinate System, which is fixed with the stars. The two coordinates are Right Ascension and Declination. Declination ranges from the North Celestial Pole to the South Celestial Pole, with the Celestial Equator being a line around the sky at the midline of those two extremes. We will use these coordinates when navigating using the SC001 and SC002 charts. There are many ways to designate stars. The most common is called the Bayer designations. The Bayer designation of a star starts with a Greek letter. The brightest star in the constellation gets “alpha” (the first letter in the Greek alphabet), the second brightest star gets “beta,” and so on. (The Greek alphabet is shown below.) The Bayer designation must also include the constellation name. There are only 24 letters in the Greek alphabet, so this system is obviously very limited. The Greek alphabet 1) Alpha 7) Eta 13) Nu 19) Tau 2) Beta 8) Theta 14) Xi 20) Upsilon 3) Gamma 9) Iota 15) Omicron 21) Phi 4) Delta 10) Kappa 16) Pi 22) Chi 5) Epsilon 11) Lambda 17) Rho 23) Psi 6) Zeta 12) Mu 18) Sigma 24) Omega A more extensive naming system is called the Flamsteed designation. -

Equatorial and Cartesian Coordinates • Consider the Unit Sphere (“Unit”: I.E

Coordinate Transforms Equatorial and Cartesian Coordinates • Consider the unit sphere (“unit”: i.e. declination the distance from the center of the (δ) sphere to its surface is r = 1) • Then the equatorial coordinates Equator can be transformed into Cartesian coordinates: right ascension (α) – x = cos(α) cos(δ) – y = sin(α) cos(δ) z x – z = sin(δ) y • It can be much easier to use Cartesian coordinates for some manipulations of geometry in the sky Equatorial and Cartesian Coordinates • Consider the unit sphere (“unit”: i.e. the distance y x = Rcosα from the center of the y = Rsinα α R sphere to its surface is r = 1) x Right • Then the equatorial Ascension (α) coordinates can be transformed into Cartesian coordinates: declination (δ) – x = cos(α)cos(δ) z r = 1 – y = sin(α)cos(δ) δ R = rcosδ R – z = sin(δ) z = rsinδ Precession • Because the Earth is not a perfect sphere, it wobbles as it spins around its axis • This effect is known as precession • The equatorial coordinate system relies on the idea that the Earth rotates such that only Right Ascension, and not declination, is a time-dependent coordinate The effects of Precession • Currently, the star Polaris is the North Star (it lies roughly above the Earth’s North Pole at δ = 90oN) • But, over the course of about 26,000 years a variety of different points in the sky will truly be at δ = 90oN • The declination coordinate is time-dependent albeit on very long timescales • A precise astronomical coordinate system must account for this effect Equatorial coordinates and equinoxes • To account -

Capricious Suntime

[Physics in daily life] I L.J.F. (Jo) Hermans - Leiden University, e Netherlands - [email protected] - DOI: 10.1051/epn/2011202 Capricious suntime t what time of the day does the sun reach its is that the solar time will gradually deviate from the time highest point, or culmination point, when on our watch. We expect this‘eccentricity effect’ to show a its position is exactly in the South? e ans - sine-like behaviour with a period of a year. A wer to this question is not so trivial. For ere is a second, even more important complication. It is one thing, it depends on our location within our time due to the fact that the rotational axis of the earth is not zone. For Berlin, which is near the Eastern end of the perpendicular to the ecliptic, but is tilted by about 23.5 Central European time zone, it may happen around degrees. is is, aer all, the cause of our seasons. To noon, whereas in Paris it may be close to 1 p.m. (we understand this ‘tilt effect’ we must realise that what mat - ignore the daylight saving ters for the deviation in time time which adds an extra is the variation of the sun’s hour in the summer). horizontal motion against But even for a fixed loca - the stellar background tion, the time at which the during the year. In mid- sun reaches its culmination summer and mid-winter, point varies throughout the when the sun reaches its year in a surprising way. -

Solar Engineering Basics

Solar Energy Fundamentals Course No: M04-018 Credit: 4 PDH Harlan H. Bengtson, PhD, P.E. Continuing Education and Development, Inc. 22 Stonewall Court Woodcliff Lake, NJ 07677 P: (877) 322-5800 [email protected] Solar Energy Fundamentals Harlan H. Bengtson, PhD, P.E. COURSE CONTENT 1. Introduction Solar energy travels from the sun to the earth in the form of electromagnetic radiation. In this course properties of electromagnetic radiation will be discussed and basic calculations for electromagnetic radiation will be described. Several solar position parameters will be discussed along with means of calculating values for them. The major methods by which solar radiation is converted into other useable forms of energy will be discussed briefly. Extraterrestrial solar radiation (that striking the earth’s outer atmosphere) will be discussed and means of estimating its value at a given location and time will be presented. Finally there will be a presentation of how to obtain values for the average monthly rate of solar radiation striking the surface of a typical solar collector, at a specified location in the United States for a given month. Numerous examples are included to illustrate the calculations and data retrieval methods presented. Image Credit: NOAA, Earth System Research Laboratory 1 • Be able to calculate wavelength if given frequency for specified electromagnetic radiation. • Be able to calculate frequency if given wavelength for specified electromagnetic radiation. • Know the meaning of absorbance, reflectance and transmittance as applied to a surface receiving electromagnetic radiation and be able to make calculations with those parameters. • Be able to obtain or calculate values for solar declination, solar hour angle, solar altitude angle, sunrise angle, and sunset angle. -

Disrupted Solar Transit at 140 Mhz Over the Mexican Array Radio Telescope Due Space Weather Events

URSI AP-RASC 2019, New Delhi, India; 09 - 15 March 2019 Disrupted Solar Transit at 140 MHz over the Mexican Array Radio Telescope due Space Weather Events *Victor De la Luz(1)(2), Julio Mejia-Ambriz(1)(2), and Americo Gonzalez(2) (1) Conacyt, Servicio de Clima Espacial Mexico, Morelia, Mexico. 58190. http://www.sciesmex.unam.mx (2) Instituto de Geofisica, Unidad Michoacan, UNAM, Morelia, Mexico. 58190. Abstract Figure 2 show two solar transits centered at peak, for 22 (green line, quiet) and 26 (blue line, close to the solar flare) In this work we present the records of the disrupted so- June, 2015. We observed clearly the changes of amplitude lar transits at 140 MHz at Mexican Array Radio Telescope of the signal. (MEXART) related with active regionsand a solar flare dur- ing the week of June 20 - 26, 2015. 4 Conclusions 1 Introduction We show that space weather, in particular solar flares, mod- ifies the antenna pattern related with solar transit in the MEXART at 140 MHz. The increase in the flux saturated The transit instrument Mexican Array Radio Telescope the instrument at June 22. For this reasson, we used the 5Th (MEXART) is located in Coeneo, Mexico. Their main pro- lateral left lobe to characterize the increase of the flux. We pose is record extra-galactic radio source to observe the observed that at peak, the flux increases 16 mV in the max- interplanetary scintillation (IPS) [3]. The radio telescope imum level at June 22, 2015 compared against the baseline have central frequency of 139.65 MHz and bandwidth of 2 of the transit in quiet conditions. -

1 Comparison of Solar Evaluation Tools

COMPARISON OF SOLAR EVALUATION TOOLS: FROM LEARNING TO PRACTICE Sophia Duluk Heather Nelson Department of Architecture Department of Architecture University of Oregon University of Oregon Eugene, OR 97403 Eugene, OR 97403 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Alison Kwok Department of Architecture University of Oregon Eugene, OR 97403 Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT obstacles to the use of software and a number of misunderstandings about principles and concepts of solar Solar tools and software have evolved in the last ten years to radiation. These can cause under- or overestimations, assist designers in evaluating a site for shading, solar access, leading to heavy energy consequences when handling daylighting design, photovoltaic placement, and passive building loads and thermal comfort. solar heating potential. This paper presents a comparative evaluation of solar site analysis tools as base cases for This study focuses on comparing six tools readily available evaluation. We present the results from on site to design professionals: Solar Transit (1), Solar Pathfinder measurements, software predictions, output accuracy, ease (http://www.solarpathfinder.com/index), Solmetric Suneye of use, design inputs needed for Passive House Planning (http://www.solmetric.com), HORIcatcher+Meteonorm Protocol (PHPP), and other criteria to discuss the (http://www.meteotest.ch/en/footernavi/solar_energy/horicat capabilities of the tools in education and in architectural cher/) and two iPhone applications. Additionally, the study design practice. We compare six tools: Solar Transit, Solar will examine shading protocols used for the Passive House Pathfinder + Solar Pathfinder Assistant software, Solmetric Planning Package (PHPP) to see how the tools compare to Suneye + Thermal Assistant Software, HORIcatcher + the PHPP shading assumptions, and determine the Meteonorm, and two iPhone applications.