Equatorial and Cartesian Coordinates • Consider the Unit Sphere (“Unit”: I.E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Planet Positions: 1 Planet Positions

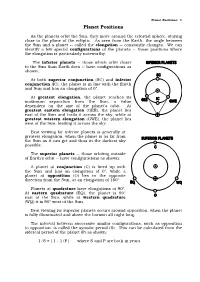

Planet Positions: 1 Planet Positions As the planets orbit the Sun, they move around the celestial sphere, staying close to the plane of the ecliptic. As seen from the Earth, the angle between the Sun and a planet -- called the elongation -- constantly changes. We can identify a few special configurations of the planets -- those positions where the elongation is particularly noteworthy. The inferior planets -- those which orbit closer INFERIOR PLANETS to the Sun than Earth does -- have configurations as shown: SC At both superior conjunction (SC) and inferior conjunction (IC), the planet is in line with the Earth and Sun and has an elongation of 0°. At greatest elongation, the planet reaches its IC maximum separation from the Sun, a value GEE GWE dependent on the size of the planet's orbit. At greatest eastern elongation (GEE), the planet lies east of the Sun and trails it across the sky, while at greatest western elongation (GWE), the planet lies west of the Sun, leading it across the sky. Best viewing for inferior planets is generally at greatest elongation, when the planet is as far from SUPERIOR PLANETS the Sun as it can get and thus in the darkest sky possible. C The superior planets -- those orbiting outside of Earth's orbit -- have configurations as shown: A planet at conjunction (C) is lined up with the Sun and has an elongation of 0°, while a planet at opposition (O) lies in the opposite direction from the Sun, at an elongation of 180°. EQ WQ Planets at quadrature have elongations of 90°. -

Sun Tool Options

Sun Study Tools Sophomore Architecture Studio: Lighting Lecture 1: • Introduction to Daylight (part 1) • Survey of the Color Spectrum • Making Light • Controlling Light Lecture 2: • Daylight (part 2) • Design Tools to study Solar Design • Architectural Applications Lecture 3: • Light in Architecture • Lighting Design Strategies Sun Tool Options 1. Paper and Pencil 2. Build a Model 3. Use a Computer The first step to any of these options is to define…. Where is the site? 1 2 Sun Study Tools North Latitude and Longitude South Longitude Latitude Longitude Sun Study Tools North America Latitude 3 United States e ud tit La Sun Study Tools New York 72w 44n 42n Site Location The site location is specified by a latitude l and a longitude L. Latitudes and longitudes may be found in any standard atlas or almanac. Chart shows the latitudes and longitudes of some North American cities. Conventions used in expressing latitudes are: Positive = northern hemisphere Negative = southern hemisphere Conventions used in expressing longitudes are: Positive = west of prime meridian (Greenwich, United Kingdom) Latitude and Longitude of Some North American Cities Negative = east of prime meridian 4 Sun Study Tools Solar Path Suns Position The position of the sun is specified by the solar altitude and solar azimuth and is a function of site latitude, solar time, and solar declination. 5 Sun Study Tools Suns Position The rotation of the earth about its axis, as well as its revolution about the sun, produces an apparent motion of the sun with respect to any point on the altitude earth's surface. The position of the sun with respect to such a point is expressed in terms of two angles: azimuth The sun's position in terms of solar altitude (a ) and azimuth (a ) solar azimuth, which is the t s with respect to the cardinal points of the compass. -

3.- the Geographic Position of a Celestial Body

Chapter 3 Copyright © 1997-2004 Henning Umland All Rights Reserved Geographic Position and Time Geographic terms In celestial navigation, the earth is regarded as a sphere. Although this is an approximation, the geometry of the sphere is applied successfully, and the errors caused by the flattening of the earth are usually negligible (chapter 9). A circle on the surface of the earth whose plane passes through the center of the earth is called a great circle . Thus, a great circle has the greatest possible diameter of all circles on the surface of the earth. Any circle on the surface of the earth whose plane does not pass through the earth's center is called a small circle . The equator is the only great circle whose plane is perpendicular to the polar axis , the axis of rotation. Further, the equator is the only parallel of latitude being a great circle. Any other parallel of latitude is a small circle whose plane is parallel to the plane of the equator. A meridian is a great circle going through the geographic poles , the points where the polar axis intersects the earth's surface. The upper branch of a meridian is the half from pole to pole passing through a given point, e. g., the observer's position. The lower branch is the opposite half. The Greenwich meridian , the meridian passing through the center of the transit instrument at the Royal Greenwich Observatory , was adopted as the prime meridian at the International Meridian Conference in 1884. Its upper branch is the reference for measuring longitudes (0°...+180° east and 0°...–180° west), its lower branch (180°) is the basis for the International Dateline (Fig. -

2. Descriptive Astronomy (“Astronomy Without a Telescope”)

2. Descriptive Astronomy (“Astronomy Without a Telescope”) http://apod.nasa.gov/apod/astropix.html • How do we locate stars in the heavens? • What stars are visible from a given location? • Where is the sun in the sky at any given time? • Where are you on the Earth? An “asterism” is two stars that appear To be close in the sky but actually aren’t In 1930 the International Astronomical Union (IAU) ruled the heavens off into 88 legal, precise constellations. (52 N, 36 S) Every star, galaxy, etc., is a member of one of these constellations. Many stars are named according to their constellation and relative brightness (Bayer 1603). Sirius α − Centauri, α-Canis declination less http://calgary.rasc.ca/constellation.htm - list than -53o not Majoris, α-Orionis visible from SC http://www.google.com/sky/ Betelgeuse https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Messier_objects (1758 – 1782) Biggest constellation – Hydra – the female water snake 1303 square degrees, but Ursa Major and Virgo almost as big. Hydrus – the male water snake is much smaller – 2243 square degrees Smallest is Crux – the Southern Cross – 68 square degrees Brief History Some of the current constellations can be traced back to the inhabitants of the Euphrates valley, from whom they were handed down through the Greeks and Arabs. Few pictorial records of the ancient constellation figures have survived, but in the Almagest AD 150, Ptolemy catalogued the positions of 1,022 of the brightest stars both in terms of celestial latitude and longitude, and of their places in 48 constellations. The Ptolemaic constellations left a blank area centered not on the present south pole but on a point which, because of precession, would have been the south pole c. -

1 the Equatorial Coordinate System

General Astronomy (29:61) Fall 2013 Lecture 3 Notes , August 30, 2013 1 The Equatorial Coordinate System We can define a coordinate system fixed with respect to the stars. Just like we can specify the latitude and longitude of a place on Earth, we can specify the coordinates of a star relative to a coordinate system fixed with respect to the stars. Look at Figure 1.5 of the textbook for a definition of this coordinate system. The Equatorial Coordinate System is similar in concept to longitude and latitude. • Right Ascension ! longitude. The symbol for Right Ascension is α. The units of Right Ascension are hours, minutes, and seconds, just like time • Declination ! latitude. The symbol for Declination is δ. Declination = 0◦ cor- responds to the Celestial Equator, δ = 90◦ corresponds to the North Celestial Pole. Let's look at the Equatorial Coordinates of some objects you should have seen last night. • Arcturus: RA= 14h16m, Dec= +19◦110 (see Appendix A) • Vega: RA= 18h37m, Dec= +38◦470 (see Appendix A) • Venus: RA= 13h02m, Dec= −6◦370 • Saturn: RA= 14h21m, Dec= −11◦410 −! Hand out SC1 charts. Find these objects on them. Now find the constellation of Orion, and read off the Right Ascension and Decli- nation of the middle star in the belt. Next week in lab, you will have the chance to use the computer program Stellar- ium to display the sky and find coordinates of objects (stars, planets). 1.1 Further Remarks on the Equatorial Coordinate System The Equatorial Coordinate System is fundamentally established by the rotation axis of the Earth. -

2 Coordinate Systems

2 Coordinate systems In order to find something one needs a system of coordinates. For determining the positions of the stars and planets where the distance to the object often is unknown it usually suffices to use two coordinates. On the other hand, since the Earth rotates around it’s own axis as well as around the Sun the positions of stars and planets is continually changing, and the measurment of when an object is in a certain place is as important as deciding where it is. Our first task is to decide on a coordinate system and the position of 1. The origin. E.g. one’s own location, the center of the Earth, the, the center of the Solar System, the Galaxy, etc. 2. The fundamental plan (x−y plane). This is often a plane of some physical significance such as the horizon, the equator, or the ecliptic. 3. Decide on the direction of the positive x-axis, also known as the “reference direction”. 4. And, finally, on a convention of signs of the y− and z− axes, i.e whether to use a left-handed or right-handed coordinate system. For example Eratosthenes of Cyrene (c. 276 BC c. 195 BC) was a Greek mathematician, elegiac poet, athlete, geographer, astronomer, and music theo- rist who invented a system of latitude and longitude. (According to Wikipedia he was also the first person to use the word geography and invented the disci- pline of geography as we understand it.). The origin of this coordinate system was the center of the Earth and the fundamental plane was the equator, which location Eratosthenes calculated relative to the parts of the Earth known to him. -

Celestial Coordinate Systems

Celestial Coordinate Systems Craig Lage Department of Physics, New York University, [email protected] January 6, 2014 1 Introduction This document reviews briefly some of the key ideas that you will need to understand in order to identify and locate objects in the sky. It is intended to serve as a reference document. 2 Angular Basics When we view objects in the sky, distance is difficult to determine, and generally we can only indicate their direction. For this reason, angles are critical in astronomy, and we use angular measures to locate objects and define the distance between objects. Angles are measured in a number of different ways in astronomy, and you need to become familiar with the different notations and comfortable converting between them. A basic angle is shown in Figure 1. θ Figure 1: A basic angle, θ. We review some angle basics. We normally use two primary measures of angles, degrees and radians. In astronomy, we also sometimes use time as a measure of angles, as we will discuss later. A radian is a dimensionless measure equal to the length of the circular arc enclosed by the angle divided by the radius of the circle. A full circle is thus equal to 2π radians. A degree is an arbitrary measure, where a full circle is defined to be equal to 360◦. When using degrees, we also have two different conventions, to divide one degree into decimal degrees, or alternatively to divide it into 60 minutes, each of which is divided into 60 seconds. These are also referred to as minutes of arc or seconds of arc so as not to confuse them with minutes of time and seconds of time. -

Positional Astronomy Coordinate Systems

Positional Astronomy Observational Astronomy 2019 Part 2 Prof. S.C. Trager Coordinate systems We need to know where the astronomical objects we want to study are located in order to study them! We need a system (well, many systems!) to describe the positions of astronomical objects. The Celestial Sphere First we need the concept of the celestial sphere. It would be nice if we knew the distance to every object we’re interested in — but we don’t. And it’s actually unnecessary in order to observe them! The Celestial Sphere Instead, we assume that all astronomical sources are infinitely far away and live on the surface of a sphere at infinite distance. This is the celestial sphere. If we define a coordinate system on this sphere, we know where to point! Furthermore, stars (and galaxies) move with respect to each other. The motion normal to the line of sight — i.e., on the celestial sphere — is called proper motion (which we’ll return to shortly) Astronomical coordinate systems A bit of terminology: great circle: a circle on the surface of a sphere intercepting a plane that intersects the origin of the sphere i.e., any circle on the surface of a sphere that divides that sphere into two equal hemispheres Horizon coordinates A natural coordinate system for an Earth- bound observer is the “horizon” or “Alt-Az” coordinate system The great circle of the horizon projected on the celestial sphere is the equator of this system. Horizon coordinates Altitude (or elevation) is the angle from the horizon up to our object — the zenith, the point directly above the observer, is at +90º Horizon coordinates We need another coordinate: define a great circle perpendicular to the equator (horizon) passing through the zenith and, for convenience, due north This line of constant longitude is called a meridian Horizon coordinates The azimuth is the angle measured along the horizon from north towards east to the great circle that intercepts our object (star) and the zenith. -

Exercise 1.0 the CELESTIAL EQUATORIAL COORDINATE

Exercise 1.0 THE CELESTIAL EQUATORIAL COORDINATE SYSTEM Equipment needed: A celestial globe showing positions of bright stars. I. Introduction There are several different ways of representing the appearance of the sky or describing the locations of objects we see in the sky. One way is to imagine that every object in the sky is located on a very large and distant sphere called the celestial sphere . This imaginary sphere has its center at the center of the Earth. Since the radius of the Earth is very small compared to the radius of the celestial sphere, we can imagine that this sphere is also centered on any person or observer standing on the Earth's surface. Every celestial object (e.g., a star or planet) has a definite location in the sky with respect to some arbitrary reference point. Once defined, such a reference point can be used as the origin of a celestial coordinate system. There is an astronomically important point in the sky called the vernal equinox , which astronomers use as the origin of such a celestial coordinate system . The meaning and significance of the vernal equinox will be discussed later. In an analogous way, we represent the surface of the Earth by a globe or sphere. Locations on the geographic sphere are specified by the coordinates called longitude and latitude . The origin for this geographic coordinate system is the point where the Prime Meridian and the Geographic Equator intersect. This is a point located off the coast of west-central Africa. To specify a location on a sphere, the coordinates must be angles, since a sphere has a curved surface. -

5 Transformation Between the International Terrestrial Refer

IERS Technical Note No. 36 5 Transformation between the International Terrestrial Refer- ence System and the Geocentric Celestial Reference System 5.1 Introduction The transformation to be used to relate the International Terrestrial Reference System (ITRS) to the Geocentric Celestial Reference System (GCRS) at the date t of the observation can be written as: [GCRS] = Q(t)R(t)W (t) [ITRS]; (5.1) where Q(t), R(t) and W (t) are the transformation matrices arising from the mo- tion of the celestial pole in the celestial reference system, from the rotation of the Earth around the axis associated with the pole, and from polar motion respec- tively. Note that Eq. (5.1) is valid for any choice of celestial pole and origin on the equator of that pole. The definition of the GCRS and ITRS and the procedures for the ITRS to GCRS transformation that are provided in this chapter comply with the IAU 2000/2006 resolutions (provided at <1> and in Appendix B). More detailed explanations about the relevant concepts, software and IERS products corresponding to the IAU 2000 resolutions can be found in IERS Technical Note 29 (Capitaine et al., 2002), as well as in a number of original subsequent publications that are quoted in the following sections. The chapter follows the recommendations on terminology associated with the IAU 2000/2006 resolutions that were made by the 2003-2006 IAU Working Group on \Nomenclature for fundamental astronomy" (NFA) (Capitaine et al., 2007). We will refer to those recommendations in the following as \NFA recommenda- tions" (see Appendix A for the list of the recommendations). -

Lecture 6: Where Is the Sun?

4.430 Daylighting Massachusetts Institute of Technology Christoph Reinhart Department of Architecture 4.430 Where is the sun? Building Technology Program Goals for This Week Where is the sun? Designing Static Shading Systems MIT 4.430 Daylighting, Instructor C Reinhart 1 1 MISC Meeting on group projects Reduce HDR image size via pfilt –x 800 –y 550 filne_name_large.pic > filename_small>.pic Note: pfilt is a Radiance program. You can find further info on pfilt by googeling: “pfilt Radiance” MIT 4.430 Daylighting, Instructor C Reinhart 2 2 Daylight Factor Hand Calculation Mean Daylight Factor according to Lynes Reinhart & LoVerso, Lighting Research & Technology (2010) Move into the building, design the facade openings, room dimensions and depth of the daylit area. Determine the required glazing area using the Lynes formula. A glazing = required glazing area A total = overall interior surface area (not floor area!) R mean = area-weighted mean surface reflectance vis = visual transmittance of glazing units = sun angle 3 ‘Validation’ of Daylight Factor Formula Reinhart & LoVerso, Lighting Research & Technology (2010) Graph of mean daylighting factor according to Lynes formula v. Radiance removed due to copyright restrictions. Source: Figure 5 in Reinhart, C. F., and V. R. M. LoVerso. "A Rules of Thumb Based Design Sequence for Diffuse Daylight." Lighting Research and Technology 42, no. 1 (2010): 7-32. Comparison to Radiance simulations for 2304 spaces. Quality control for simulations. LEED 2.2 Glazing Factor Formula Graph of mean daylighting factor according to LEED 2.2 v. Radiance removed due to copyright restrictions. Source: Figure 11 in Reinhart, C. F., and V. -

Field Astronomy Circumpolar Star at Elongation ➢ at Elongation a Circumpolar Star Is at the Farthest Position from the Pole Either in the East Or West

Field Astronomy Circumpolar Star at Elongation ➢ At elongation a circumpolar star is at the farthest position from the pole either in the east or west. ➢ When the star is at elongation (East or West), which is perpendicular to the N-S line. ➢ Thus the ZMP is 90° as shown in the figure below. Distances between two points on the Earth’s surface ➢ Direct distance From the fig. above, in the spherical triangle APB P = Difference between longitudes of A and B BP = a = co-latitude of B = 90 – latitude of B AP = b = co-latitude of A = 90 – latitude of A Apply the cosine rule: cosp− cos a cos b CosP = sinab sin Find the value of p = AB Then the distance AB = arc length AB = ‘p’ in radians × radius of the earth ➢ Distance between two points on a parallel of latitude Let A and B be the two points on the parallel latitude θ. Let A’ and B’ be the corresponding points on the equator having the same longitudes (ФB, ФA). Thus from the ∆ O’AB AB = O’B(ФB - ФA) From the ∆ O’BO o O’B = OB’ sin (90- θ) Since =BOO ' 90 = R cos θ where R=Radius of the Earth. AB= (ФB - ФA) R cos θ where ФB , ФA are longitudes of B and A in radians. Practice Problems 1. Find the shortest distance between two places A and B on the earth for the data given below: Latitude of A = 14° N Longitude of A = 60°30‘E Latitude of B = 12° N Longitude of A = 65° E Find also direction of B from A.