The Dunwich Cycle Where the Old Gods Wait by Robert M. Price the Dunwich Horror

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019-05-06 Catalog P

Pulp-related books and periodicals available from Mike Chomko for May and June 2019 Dianne and I had a wonderful time in Chicago, attending the Windy City Pulp & Paper Convention in April. It’s a fine show that you should try to attend. Upcoming conventions include Robert E. Howard Days in Cross Plains, Texas on June 7 – 8, and the Edgar Rice Burroughs Chain of Friendship, planned for the weekend of June 13 – 15. It will take place in Oakbrook, Illinois. Unfortunately, it doesn’t look like there will be a spring edition of Ray Walsh’s Classicon. Currently, William Patrick Maynard and I are writing about the programming that will be featured at PulpFest 2019. We’ll be posting about the panels and presentations through June 10. On June 17, we’ll write about this year’s author signings, something new we’re planning for the convention. Check things out at www.pulpfest.com. Laurie Powers biography of LOVE STORY MAGAZINE editor Daisy Bacon is currently scheduled for release around the end of 2019. I will be carrying this book. It’s entitled QUEEN OF THE PULPS. Please reserve your copy today. Recently, I was contacted about carrying the Armchair Fiction line of books. I’ve contacted the publisher and will certainly be able to stock their books. Founded in 2011, they are dedicated to the restoration of classic genre fiction. Their forté is early science fiction, but they also publish mystery, horror, and westerns. They have a strong line of lost race novels. Their books are illustrated with art from the pulps and such. -

GUÍA De Creación De Personaje CTHULHU

Foundation for Archeological Research Guía para nuevos miembros Una guía no-oficial para crear investigadores para el juego de rol “La Llamada de Cthulhu” ” publicado en España por Edge Entertainment bajo licencia de Chaosium. Para ser utilizado principalmente en “Los Misterios de Bloomfield”-“The Bloomfield Mysteries”, una adaptación de “La Sombra de Saros”, campaña escrita por Xabier Ugalde, para su uso en las aulas de Primaria en las áreas de Ciencias Sociales, Lengua Castellana y Lengua Extranjera: Inglés Adaptado para Educación Primaria por: ÓscarRecio Coll [email protected] https://jueducacion.com/ El Copyright de las ilustraciones de La Llamada de Cthulhu y de La Sombra de Saros además de otras presentes en este material así como la propiedad intelectual/comercial/empresarial y derechos de las mismas son exclusiva de sus autores y/o de las compañías y editoriales que sean propietarias o hayan comprado los citados derechos sobre las obras y posean sobre ellas el derecho a que se las elimine de esta publicación de tal manera que sus derechos no queden vulnerados en ninguna forma o modo que pudiera contravenir su autoría para particulares y/o empresas que las hayan utilizado con fines comerciales y/o empresariales. Esta compilación no tiene ningún uso comercial ni ánimo de lucro y está destinada exclusivamente a su utilización dentro del ámbito escolar y su finalidad es completamente didáctica como material de desarrollo y apoyo para la dinamización de contenidos en las diferentes áreas que componen la Educación Primaria. Bienvenidos/as a la F.A.R. (Fundación de Investigaciones Arqueológicas), en este sencillo manual encontrarás las instrucciones para ser parte de nuestra fundación y completar tu registro como miembro. -

Malleus Monstrorumsampleexpanded English File Edition Is Published by Chaosium Inc

Sample file —EXPANDED ENGLISH EDITION IN 380 ENTRIES— by Scott David Aniolowski with Sandy Petersen & Lynn Willis Additional Material by: David Conyers, Keith Herber, Kevin Ross, ChadSample J. Bowser, Shannon file Appel, Christian von Aster, Joachim A. Hagen, Florian Hardt, Frank Heller, Peter Schott, Steffen Schuütte, Michael Siefner, Jan Cristof Steines, Holger Göttmann, Wolfang Schiemichen, Ingo Ahrens, and friends. For fuller Author credits see pages 4 and 288. Project & Layout: Charlie Krank Cover Painting: Lee Gibbons Illustrated by: Pascal D. Bohr, Konstantyn Debus, Nils Eckhardt, Thomas Ertmer, Kostja Kleye, Jan Kluczewitz, Christian Küttler, Klaas Neumann, Patrick Strietzel, Jens Weber, Maria Luisa Witte, Lydia Ortiz, Paul Carrick. Art direction and visual concept: Konstantyn Debus (www.yllustration.com) Participants in the German Edition: Frank Heller, Konstantyn Debus, Peter Schott, Thomas M. Webhofer, Ingo Ahrens, Jens Kaufmann, Holger Göttmann, Christina Wessel, Maik Krüger, Holger Rinke, Andreas Finkernagel, 15brötchenmann Find more information at www.pegasus.de German to English Translation: Bill Walsh Layout Assistance: Alan Peña, Lydia Ortiz Chaosium is: Lynn Willis, Charlie Krank, Dustin Wright, Fergie, and a few odd critters. A CHAOSIUM PUBLICATION • 2006 M’bwa, megalodon, the Million Favoured Ones, the Complete Credits mind parasites, the miri nigri, M’nagalah, Mordiggian, moose, M’Tlblys, the nioth-korghai, Nug & Yeb, octo- Scott David Aniolowski: the children of Abhoth, pus, Ossadagowah, Othuum, the minions of Othuum, -

Extraterrestrial Places in the Cthulhu Mythos

Extraterrestrial places in the Cthulhu Mythos 1.1 Abbith A planet that revolves around seven stars beyond Xoth. It is inhabited by metallic brains, wise with the ultimate se- crets of the universe. According to Friedrich von Junzt’s Unaussprechlichen Kulten, Nyarlathotep dwells or is im- prisoned on this world (though other legends differ in this regard). 1.2 Aldebaran Aldebaran is the star of the Great Old One Hastur. 1.3 Algol Double star mentioned by H.P. Lovecraft as sidereal The double star Algol. This infrared imagery comes from the place of a demonic shining entity made of light.[1] The CHARA array. same star is also described in other Mythos stories as a planetary system host (See Ymar). The following fictional celestial bodies figure promi- nently in the Cthulhu Mythos stories of H. P. Lovecraft and other writers. Many of these astronomical bodies 1.4 Arcturus have parallels in the real universe, but are often renamed in the mythos and given fictitious characteristics. In ad- Arcturus is the star from which came Zhar and his “twin” dition to the celestial places created by Lovecraft, the Lloigor. Also Nyogtha is related to this star. mythos draws from a number of other sources, includ- ing the works of August Derleth, Ramsey Campbell, Lin Carter, Brian Lumley, and Clark Ashton Smith. 2 B Overview: 2.1 Bel-Yarnak • Name. The name of the celestial body appears first. See Yarnak. • Description. A brief description follows. • References. Lastly, the stories in which the celes- 3 C tial body makes a significant appearance or other- wise receives important mention appear below the description. -

The Dunwich Horror

The Dunwich Horror Cthulhu Mythos by Howard Phillips Lovecraft, 1890-1937 Written: 1928 Published: 1929 in »Weird Tales« J J J J J I I I I I Table of Contents I … thru … X J J J J J I I I I I “Gorgons, and Hydras, and Chimaeras—dire stories of Celaeno and the Harpies—may reproduce themselves in the brain of superstition—but they were there before. They are transcripts, types—the archetypes are in us, and eternal. How else should the recital of that which we know in a waking sense to be false come to affect us at all? Is it that we naturally conceive terror from such objects, considered in their capacity of being able to inflict upon us bodily injury? O, least of all! These terrors are of older standing. They date beyond body-or without the body, they would have been the same… That the kind of fear here treated is purely spiritual—that it is strong in proportion as it is objectless on earth, that it predominates in the period of our sinless infancy— are difficulties the solution of which might afford some probable insight into our ante-mundane condition, and a peep at least into the shadowland of pre- existence .” —Charles Lamb: Witches and Other Night-Fears In the isolated, desolate, decrepit village of Dunwich, Massachusetts, Wilbur Whateley is the hideous son of Lavinia Whateley, a deformed and unstable albino mother, and an unknown father (alluded to in passing by mad Old Whateley, as "Yog-Sothoth"). Strange events surround his birth and precocious development. -

Dunwich Horror by Sean Branney with Andrew Leman

Dark Adventure Radio Theatre: The Dunwich Horror by Sean Branney With Andrew Leman Based on "The Dunwich Horror" by H.P. Lovecraft Read-along Script ©2008, HPLHS, Inc., all rights reserved Static, radio tuning, snippet of 30s song, more tuning, static dissolves to: Dark Adventure Radio theme music. ANNOUNCER Tales of intrigue, adventure, and the mysterious occult that will stir your imagination and make your very blood run cold. Music crescendo. ANNOUNCER This is Dark Adventure Radio Theatre, with your host Chester Langfield. Today’s episode: H.P. Lovecraft’s “The Dunwich Horror”. Music diminishes. CHESTER LANGFIELD The hills of Western Massachusetts contain dark and terrible secrets. Strange families keep to themselves and practice rites of ancient and unspeakable black magic. These dreadful and unholy rituals give birth to a monstrosity beyond imagination, a monstrosity that threatens mankind itself! Can a brave handful of intrepid scholars hope to confront the otherwordly destruction of “The Dunwich Horror”? But first a word from our sponsor. A few piano notes from the Fleur de Lys jingle. CHESTER LANGFIELD When I sit down to enjoy a meal, the first thing I do is light up a Fleur de Lys cigarette. Not only do they enhance the taste of food, Fleur de Lys aid in the digestive process. Our cigarettes are made from finer costlier tobaccos than other brands, providing you with the very best in freshness and flavor. So, for the sake of digestion, during and after meals be sure to smoke Fleur de Lys! Dark Adventure lead-in music. DART: The Dunwich Horror 2. -

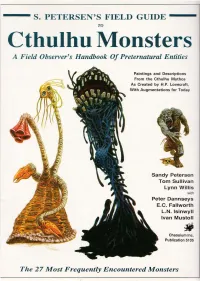

Cthulhu Monsters a Field Observer's Handbook of Preternatural Entities

--- S. PETERSEN'S FIELD GUIDE TO Cthulhu Monsters A Field Observer's Handbook Of Preternatural Entities Paintings and Descriptions From the Cthulhu Mythos As Created by H.P. Lovecraft, With Augmentations for Today Sandy Petersen Tom Sullivan Lynn Willis with Peter Dannseys E.C. Fallworth L.N. Isinwyll Ivan Mustoll Chaosium Inc. Publication 5105 The 27 Most Frequently Encountered Monsters Howard Phillips Lovecraft 1890 - 1937 t PETERSEN'S Field Guide To Cthulhu :Monsters A Field Observer's Handbook Of Preternatural Entities Sandy Petersen conception and text TOIn Sullivan 27 original paintings, most other drawings Lynn ~illis project, additional text, editorial, layout, production Chaosiurn Inc. 1988 The FIELD GUIDe is p «blished by Chaosium IIIC . • PETERSEN'S FIELD GUIDE TO CfHUU/U MONSTERS is copyrighl e1988 try Chaosium IIIC.; all rights reserved. _ Similarities between characters in lhe FIELD GUIDE and persons living or dead are strictly coincidental . • Brian Lumley first created the ChJhoniwu . • H.P. Lovecraft's works are copyright e 1963, 1964, 1965 by August Derleth and are quoted for purposes of ilIustraJion_ • IflCide ntal monster silhouelles are by Lisa A. Free or Tom SU/livQII, and are copyright try them. Ron Leming drew the illustraJion of H.P. Lovecraft QIId tlu! sketclu!s on p. 25. _ Except in this p«blicaJion and relaJed advertising, artwork. origillalto the FIELD GUIDE remains the property of the artist; all rights reserved . • Tire reproductwn of material within this book. for the purposes of personal. or corporaJe profit, try photographic, electronic, or other methods of retrieval, is prohibited . • Address questions WId commel11s cOlICerning this book. -

Cthulhu Lives!: a Descriptive Study of the H.P. Lovecraft Historical Society

CTHULHU LIVES!: A DESCRIPTIVE STUDY OF THE H.P. LOVECRAFT HISTORICAL SOCIETY J. Michael Bestul A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2006 Committee: Dr. Jane Barnette, Advisor Prof. Bradford Clark Dr. Marilyn Motz ii ABSTRACT Dr. Jane Barnette, Advisor Outside of the boom in video game studies, the realm of gaming has barely been scratched by academics and rarely been explored in a scholarly fashion. Despite the rich vein of possibilities for study that tabletop and live-action role-playing games present, few scholars have dug deeply. The goal of this study is to start digging. Operating at the crossroads of art and entertainment, theatre and gaming, work and play, it seeks to add the live-action role-playing game, CTHULHU LIVES, to the discussion of performance studies. As an introduction, this study seeks to describe exactly what CTHULHU LIVES was and has become, and how its existence brought about the H.P. Lovecraft Historical Society. Simply as a gaming group which grew into a creative organization that produces artifacts in multiple mediums, the Society is worthy of scholarship. Add its humble beginnings, casual style and non-corporate affiliation, and its recent turn to self- sustainability, and the Society becomes even more interesting. In interviews with the artists behind CTHULHU LIVES, and poring through the archives of their gaming experiences, the picture develops of the journey from a small group of friends to an organization with influences and products on an international scale. -

The Weird and Monstrous Names of HP Lovecraft Christopher L Robinson HEC-Paris, France

names, Vol. 58 No. 3, September, 2010, 127–38 Teratonymy: The Weird and Monstrous Names of HP Lovecraft Christopher L Robinson HEC-Paris, France Lovecraft’s teratonyms are monstrous inventions that estrange the sound patterns of English and obscure the kinds of meaning traditionally associ- ated with literary onomastics. J.R.R. Tolkien’s notion of linguistic style pro- vides a useful concept to examine how these names play upon a distance from and proximity to English, so as to give rise to specific historical and cultural connotations. Some imitate the sounds and forms of foreign nomen- clatures that hold “weird” connotations due to being linked in the popular imagination with kabbalism and decadent antiquity. Others introduce sounds-patterns that lie outside English phonetics or run contrary to the phonotactics of the language to result in anti-aesthetic constructions that are awkward to pronounce. In terms of sense, teratonyms invite comparison with the “esoteric” words discussed by Jean-Jacques Lecercle, as they dimi- nish or obscure semantic content, while augmenting affective values and heightening the reader’s awareness of the bodily production of speech. keywords literary onomastics, linguistic invention, HP Lovecraft, twentieth- century literature, American literature, weird fiction, horror fiction, teratology Text Cult author H.P. Lovecraft is best known as the creator of an original mythology often referred to as the “Cthulhu Mythos.” Named after his most popular creature, this mythos is elaborated throughout Lovecraft’s poetry and fiction with the help of three “devices.” The first is an outlandish array of monsters of extraterrestrial origin, such as Cthulhu itself, described as “vaguely anthropoid [in] outline, but with an octopus-like head whose face was a mass of feelers, a scaly, rubbery-looking body, prodigious claws on hind and fore feet, and long, narrow wings behind” (1963: 134). -

Errata for H. P. Lovecraft: the Fiction

Errata for H. P. Lovecraft: The Fiction The layout of the stories – specifically, the fact that the first line is printed in all capitals – has some drawbacks. In most cases, it doesn’t matter, but in “A Reminiscence of Dr. Samuel Johnson”, there is no way of telling that “Privilege” and “Reminiscence” are spelled with capitals. THE BEAST IN THE CAVE A REMINISCENCE OF DR. SAMUEL JOHNSON 2.39-3.1: advanced, and the animal] advanced, 28.10: THE PRIVILEGE OF REMINISCENCE, the animal HOWEVER] THE PRIVILEGE OF 5.12: wondered if the unnatural quality] REMINISCENCE, HOWEVER wondered if this unnatural quality 28.12: occurrences of History and the] occurrences of History, and the THE ALCHEMIST 28.20: whose famous personages I was] whose 6.5: Comtes de C——“), and] Comtes de C— famous Personages I was —”), and 28.22: of August 1690 (or] of August, 1690 (or 6.14: stronghold for he proud] stronghold for 28.32: appear in print.”), and] appear in the proud Print.”), and 6.24: stones of he walls,] stones of the walls, 28.34: Juvenal, intituled “London,” by] 7.1: died at birth,] died at my birth, Juvenal, intitul’d “London,” by 7.1-2: servitor, and old and trusted] servitor, an 29.29: Poems, Mr. Johnson said:] Poems, Mr. old and trusted Johnson said: 7.33: which he had said had for] which he said 30.24: speaking for Davy when others] had for speaking for Davy when others 8.28: the Comte, the pronounced in] the 30.25-26: no Doubt but that he] no Doubt that Comte, he pronounced in he 8.29: haunted the House of] haunted the house 30.35-36: to the Greater -

Cthulhu Through the Ages Is Copyright © 2014 by Chaosium Inc

AUTHORS Mike Mason, Pedro Ziviani, John French, and Chad Bowser EDITING Mike Mason and Dustin Wright CARTOGRAPHY Stephanie McAlea INVESTIGATOR SHEETS Dean Engelhardt LAYOUT Nicholas Nacario COVER ILLUSTRATION Paul Carrick INTERIOR ILLUSTRATIONS Steven Gilberts, Sam Lamont, Florian Stitz, Paul Carrick, Goomi, Raymond Bayless, Nicholas Nacario. Some images were taken from Wikicommons and are in the public domain. THANKS TO Alan Bligh, John French, Matt Anderson, Penda Tomlin- son, and Dustin Wright. A special thanks to all of our 7th edition kickstarter backers who helped make this book possible. This supplement is best used with the roleplaying game CALL OF CTHULHU, available separately. Find more Chaosium Inc. products at www.chaosium.com Howard Phillips Lovecraft 1890 - 1937 Cthulhu Through the Ages is copyright © 2014 by Chaosium Inc. All rights reserved. The names of public personalities may be referred to, but any resemblance of a scenario character to persons liv- ing or dead is strictly coincidental. Except in this publication and associated advertising, all illustrations for CTHULHU THROUGH THE AGES remain the property of the artists, who otherwise reserve all rights. This adventure pack is best used with the roleplaying game CALL OF CTHULHU, available separately. Find more Chaosium Inc. products at www.chaosium.com Item # 23146 ISBN10: 1568824386 ISBN13: 978-1568824383 Printed in USA Contents Introduction ������������������������������������������������������������������������ 5 Cthulhu Invictus ������������������������������������������������������������������ -

H. P. Lovecraft-A Bibliography.Pdf

X-'r Art Hi H. P. LOVECRAFT; A BIBLIOGRAPHY compiled by Joseph Payne/ Brennan Yale University Library BIBLIO PRESS 1104 Vermont Avenue, N. W. Washington 5, D. C. Revised edition, copyright 1952 Joseph Payne Brennan Original from Digitized by GOO UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA L&11 vie 2. THE SHUNNED HOUSE. Athol, Mass., 1928. bds., labels, uncut. o. p. August Derleth: "Not a published book. Six or seven copies hand bound by R. H. Barlow in 1936 and sent to friends." Some stapled in paper covers. A certain number of uncut, unbound but folded sheets available. Following is an extract from the copyright notice pasted to the unbound sheets: "Though the sheets of this story were printed and marked for copyright in 1928, the story was neither bound nor cir- culated at that time. A few copies were bound, put under copyright, and circulated by R. H. Barlow in 1936, but the first wide publication of the story was in the magazine, WEIRD TALES, in the following year. The story was orig- inally set up and printed by the late W. Paul Cook, pub- lisher of THE RECLUSE." FURTHER CRITICISM OF POETRY. Press of Geo. G. Fetter Co., Louisville, 1952. 13 p. o. p. THE CATS OF ULTHAR. Dragonfly Press, Cassia, Florida, 1935. 10 p. o. p. Christmas, 1935. Forty copies printed. LOOKING BACKWARD. C. W. Smith, Haverhill, Mass., 1935. 36 p. o. p. THE SHADOW OVER INNSMOUTH. Visionary Press, Everett, Pa., 1936. 158 p. o. p. Illustrations by Frank Utpatel. The only work of the author's which was published in book form during his lifetime.