Social Process Theories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNIT 9 CRIMINOLOGY THEORIES Criminological Theories

UNIT 9 CRIMINOLOGY THEORIES Criminological Theories Structure 9.1 Introduction 9.2 Objectives 9.3 The Study of Criminology 9.4 What is Criminology? 9.5 Brief History of Criminology 9.6 Classical School of Criminology 9.6.1 Pre Classical School 9.6.2 Classical School of Criminology 9.6.3 Neo Classical School 9.7 Positive School of Criminology 9.8 Ecological School of Criminology 9.9 Theories Related to Physical Appearance 9.9.1 Phsiognomy and Phrenology 9.9.2 Criminal Anthropology: Lombroso to Goring 9.9.3 Body Type Theories: Sheldon to Cortes 9.10 Biological Factors and Criminal Behaviour 9.10.1 Chromosomes and Crime 9.10.2 Family Studies 9.10.3 Twin and Adoption Studies 9.10.4 Neurotransmitters 9.10.5 Hormones 9.10.6 The Autonomic Nervous System 9.11 Psychoanalytical Theories of Crime 9.11.1 Psychanalytic Explanations of Criminal Behaviour 9.12 Sociological Theories of Criminal Behaviour 9.12.1 Durkhiem, Anomie and Modernisation 9.12.2 Merton’s Strain Theory 9.12.3 Sutherland’s Differential Association Theory 9.13 Critical Criminology 9.13.1 Marxim and Marxist Criminology 9.14 Control Theories 9.14.1 Drift and Neutralisation 9.14.2 Hirschi’s Social Control 9.14.3 Containment Theory 9.14.4 Labeling Theory 9.15 Conflict Theories 9.15.1 Sellin’s Culture Conflict Theory 9.15.2 Vold’s Group Conflict Theory 9.15.3 Quinney’s Theory of the Social Reality of Crime 9.15.4 Turk’s Theory of Criminalisation 9.15.5 Chambliss and Seidman’s Analysis of the Criminal Justice System 5 Theories and Perspectives 9.16 Summary in Criminal Justice 9.17 Terminal Questions 9.18 Answers and Hints 9.19 References and Suggested Readings 9.1 INTRODUCTION Criminology is the scientific approach towards studying criminal behaviour. -

The Growth of Criminological Theories

THE GROWTH OF CRIMINOLOGICAL THEORIES Jonathon M. Heidt B.A., University of Montana, 2000 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS In the School of Criminology OJonathon M. Heidt 2003 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY November 2003 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: Jonathon Heidt Degree: M.A. Title of Thesis: The Growth of Criminological Theories Examining Committee: Chair: ~ridnkurtch,P~JJ$ . D;. Robert ~ordoi,kh.~. Senior Supervisor Dr. Elizabeth Elliott, Ph.D. Member Sociology Department University at Albany - SUNY Date Approved: PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENCE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser University the right to lend my thesis, project or extended essay (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this work for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Title of Thesis/Project/Extended Essay The Growth of Criminological Theories Author: Name ABSTRACT In the last 50 years, an extensive array of theories has appeared within the field of criminology, many generated by the discipline of sociology. -

Introduction to Criminology

PART 1 © Nevarpp/iStockphoto/Getty Images Introduction to Criminology CHAPTER 1 Crime and Criminology. 3 CHAPTER 2 The Incidence of Crime . 35 1 © Tithi Luadthong/Shutterstock CHAPTER 1 Crime and Criminology Crime and the fear of crime have permeated the fabric of American life. —Warren E. Burger, Chief Justice, U.S. Supreme Court1 Collective fear stimulates herd instinct, and tends to produce ferocity toward those who are not regarded as members of the herd. —Bertrand Russell2 OBJECTIVES • Define criminology, and understand how this field of study relates to other social science disciplines. Pg. 4 • Understand the meaning of scientific theory and its relationship to research and policy. Pg. 8 • Recognize how the media shape public perceptions of crime. Pg. 19 • Know the criteria for establishing causation, and identify the attributes of good research. Pg. 13 • Understand the politics of criminology and the importance of social context. Pg. 18 • Define criminal law, and understand the conflict and consensus perspectives on the law. Pg. 5 • Describe the various schools of criminological theory and the explanations that they provide. Pg. 9 of the public’s concern about the safety of their com- Introduction munities, crime is a perennial political issue that can- Crime is a social phenomenon that commands the didates for political office are compelled to address. attention and energy of the American public. When Dealing with crime commands a substantial por- crime statistics are announced or a particular crime tion of the country’s tax dollars. Criminal justice sys- goes viral, the public demands that “something be tem operations (police, courts, prisons) cost American done.” American citizens are concerned about their taxpayers over $270 billion annually. -

Sociological Theories of Deviance: Definitions & Considerations

Sociological Theories of Deviance: Definitions & Considerations NCSS Strands: Individuals, Groups, and Institutions Time, Continuity, and Change Grade level: 9-12 Class periods needed: 1.5- 50 minute periods Purpose, Background, and Context Sociologists seek to understand how and why deviance occurs within a society. They do this by developing theories that explain factors impacting deviance on a wide scale such as social frustrations, socialization, social learning, and the impact of labeling. Four main theories have developed in the last 50 years. Anomie: Deviance is caused by anomie, or the feeling that society’s goals or the means to achieve them are closed to the person Control: Deviance exists because of improper socialization, which results in a lack of self-control for the person Differential association: People learn deviance from associating with others who act in deviant ways Labeling: Deviant behavior depends on who is defining it, and the people in our society who define deviance are usually those in positions of power Students will participate in a “jigsaw” where they will become knowledgeable in one theory and then share their knowledge with the rest of the class. After all theories have been presented, the class will use the theories to explain an historic example of socially deviant behavior: Zoot Suit Riots. Objectives & Student Outcomes Students will: Be able to define the concepts of social norms and deviance 1 Brainstorm behaviors that fit along a continuum from informal to formal deviance Learn four sociological theories of deviance by reading, listening, constructing hypotheticals, and questioning classmates Apply theories of deviance to Zoot Suit Riots that occurred in the 1943 Examine the role of social norms for individuals, groups, and institutions and how they are reinforced to maintain a order within a society; examine disorder/deviance within a society (NCSS Standards, p. -

Sociology 4111 (Uggen): Deviant Behavior Midterm Review, Spring 2004

Sociology 4111 (Uggen): Deviant Behavior Midterm Review, Spring 2004 PART I: BASIC CONCEPTS -- DEVIANCE, CONTROL, AND CAREERS I. Social Facts and Social Constructions II. Defining Deviance a. Clinard’s Definitions of Deviance (Statistical, Absolutist, Reactivist, Normative) b. Adlers’ definition’s i. Deviance as violation of social norms (Attitudes, Behaviors, Conditions, Prescriptive norms, Proscriptive norms) ii. Role iii. Subcultures iv. Power v. Moral entrepreneurs c. Kai Erikson (1966) III. Differences between Criminology and Deviance a. Piece in The Criminologist: b. Heckert: positive deviance i. Altruism (hero) ii. Charisma (dictator) iii. Innovation (artist) iv. Supra-Conformity (4.0) v. Innate/Ascribed (beauty) vi. Ex-Deviant (saved) c. Middle Class norms - Typology of Deviance IV. Social Controls and the Hobbesian Problem of Order a. Thomas Hobbes i. “Hobbesian problem of order” ii. How can we create a society in which self-interested people don’t use force and fraud to satisfy their (criminal, sexual, substance-abusing …) wants? iii. 3 “solutions” to Hobbesian dilemma 1. Normative 2. Exchange 3. Conflict iv. Informal social controls v. Formal social controls b. social controls and constructions i. Clinard: Deviant Events in Context ii. Joel Best: Social Constructionism c. Race and formal control i. Anderson on police as social control ii. Local perspective/Why focus on police? V. Introduction to Deviant Careers (of people, firms, nations…) a. Becoming Deviant b. Phases of the Deviant Career 1 VI. Subcultures, Power, and “Unconventional Sentimentality” (5 min. video: The Wall) a. Chambliss: Saints and Roughnecks b. Sanchez Jankowski: Joining a Gang c. Fox: Real Punks and Pretenders PART II: THEORIES OF DEVIANCE AND SOCIETAL REACTION VII. -

Deviance and Social Control

Deviance and Social Control Summary of Topics Deviance and Social Control Functionalism and Deviance Symbolic Interactionism and Deviance Conflict Theory and Deviance Crime and Punishment What is Deviance? 1 Deviance and Social Control Deviance is the violation of social norms. It is difficult to define because not everyone agrees on what should be considered deviant behavior. The Nature of Deviance Deviance is behavior that departs from societal or group norms. Deviance is a matter of social definition–it can vary from group to group and society to society. In a diverse society,it is often difficult to agree on what is or is not deviant behavior. 2 Deviance may be either positive or negative. Negative deviance involves behavior that fails to meet accepted norms. People expressing negative deviance either reject the norms, misinterpret the norms, or are unaware of the norms. Positive deviance involves overconformity to norms. Positive deviants idealize group norms. Positive deviance can be as disruptive and hard to manage as negative deviance. The Nature of Deviance For a sociologist, a deviant is a person who has violated one or more of society’s most highly valued norms. Reactions to deviants are usually negative and involve attempts to change or control the deviant behavior. 3 Social Control Without social control– ways to promote conformity to norms–social life would be unpredictable. There are two broad types of social control: internal and external. What is internal social control? This type of social control lies within the individual. You are practicing internal social control when you do something because you know it is the right thing to do or when you don’t do something because you know it would be wrong. -

Social Structure, Culture, and Crime: Assessing Kornhauser’S Challenge to Criminology1

6 Social Structure, Culture, and Crime: Assessing Kornhauser’s Challenge to Criminology1 Ross L. Matsueda Ruth Kornhauser’s (1978) Social Sources of Delinquency has had a lasting infl uence on criminological theory and research. This infl uence consists of three contributions. First, Kornhauser (1978) developed a typology of criminological theories—using labels social disorganization, control, strain, and cultural devi- ance theories—that persists today. She distinguished perspectives by assump- tions about social order, motivation, determinism, and level of explanation, as well as by implications for causal models of delinquency. Second, Kornhauser addressed fundamental sociological concepts, including social structure, culture, and social situations, and provided a critical evaluation of their use within differ- ent theoretical perspectives. Third, she helped foster a resurgence of interest in social control and social disorganization theories of crime (e.g., Gottfredson and Hirschi 1990; Hirschi 1969; Sampson and Laub 1993; Bursik and Webb 1982; Kubrin and Weitzer 2003; Sampson and Groves 1989), both indirectly via the infl uence of an early version of the manuscript that would become Social Sources (see Chapter 3 in this volume) on Hirschi’s (1969) Causes of Delinquency , and directly via the infl uence of her book on the revitalization of social disorgani- zation theories of crime. Kornhauser’s infl uence on the writings of Hirschi, Bursik, and Sampson was particularly signifi cant and positive, as control and disorganization theo- ries came to dominate the discipline, stimulating a large body of research that increased our understanding of conventional institutional control of crime and delinquency through community organization, family life, and school effects. -

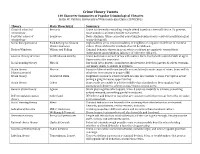

Crime Theory Tweets 140 Character Summaries of Popular Criminological Theories Justin W

Crime Theory Tweets 140 Character Summaries of Popular Criminological Theories Justin W. Patchin, University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire (CRMJ 301) Theory Main Theorist(s) Summary Classical school of Beccaria Crime is inherently rewarding. People offend based on a free will choice. To prevent, criminology must punish so potential benefit not worth it. Positivist school of Lombroso Born criminals. Crime caused by something beyond person’s control (usually biological criminology or psychological). Social disorganization Park & Burgess; Shaw & High mobility areas result in inability of neighbors to organize in defense of common McKay; Sampson values. Physical disorder symbols of social breakdown. Broken Windows Wilson and Kelling Criminal behavior thrives in areas where residents are apathetic toward their environment and neighbors (absence of collective efficacy). General theory of crime Gottfredson & Hirschi Crime & deviance a result of low self-control. One’s level of self-control stabile at age 8. Opportunity also important. Social bonding theory Hirschi Our bond (attachment, commitment, involvement, belief) to parents & others restrains our innate desire to engage in deviance. Strain theory Merton Pursuit of American Dream (wealth accumulation) is main cause of crime. Some will do (classic/anomie) whatever is necessary to acquire $$$. Strain theory Cloward & Ohlin Illegitimate means to achieve wealth are also inaccessible to some. Perception is that joining a gang increases opportunities. Strain theory Cohen Some youth are unable to achieve middle-class standards so they supplant legit pursuits with desire to achieve status/respect among peers. General strain theory Agnew Strain plus negative affect equals crime. 3 sources: inability to achieve; something valued removed; something painful introduced. -

Readings for Graduate Criminology Comprehensive Exam

READINGS FOR GRADUATE CRIMINOLOGY COMPREHENSIVE EXAM The following subdivisions are simply meant to be a heuristic device. They are not necessarily mutually exclusive or exhaustive. Note: Students are responsible for the last 5 years of articles in scholarly journals related to the area including Criminology, Criminology and Public Policy, and related papers published in the American Sociological Review, the American Journal of Sociology, and Social Forces and all other top journals. Social Disorganization and the Chicago School Bursik, R.J. 1988. "Social Disorganization theories of crime and delinquency: Problems and Prospects." Criminology 26:519-552. Morenoff, J., R. Sampson and S. Raudenbush. 2001. “Neighborhood inequality, collective efficacy, and the spatial dynamics of urban violence.” Criminology 39 (3): 517-559. Park, Robert E. 1915. “The City: Suggestions for the Investigation of Human Behavior in the City Environment. American Journal of Sociology 20: 577-612. Rose, D. and T. Clear. 1998. "Incarceration, social capital and crime: implications for social disorganization theory." Criminology 36:441-479. Sampson, R. 2012. The Great American City: Chicago and the Enduring Neighborhood Effect. University of Chicago Press. Sampson, R., S.W. Raudenbush and F. Earls. 1997."Neighborhoods and violent crime: A multilevel study of collective efficacy." Science 277: 918-924. Sampson, R., and Groves, W.B. (1989). “Community Structure and Crime: Testing Social- Disorganization Theory.” American Journal of Sociology 94 (4): 774-802. Shaw, Clifford R., and Henry D. McKay. 1942. Juvenile Delinquency in Urban Areas. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Differential Association and Social Learning Theories Akers, R. L. 1998. Social Learning and Social Structure: A General Theory of Crime and Deviance. -

Labeling Theory

Sociology Virtual Learning High School/Lesson 33 Symbolic Interactionism & Deviance May 5, 2020 Sociology Lesson: May 6, 2020 Objective/Learning Target: The student will understand the symbolic interactionism theory of deviance. Warm Up: Review: Think back to when we learned about culture. Is culture inherited or learned? What do sociologists say? Warm Up: Is culture inherited or learned? What do sociologists say? Culture is learned. If culture is learned, is deviance learned? Warm Up: Is culture inherited or learned? What do sociologists say? Culture is learned. If culture is learned, is deviance learned? Sociologists believe that deviance is a learned behavior that is culturally transmitted. Lesson/Activity Introduction: Think back to the very beginning of the semester when we learned about the three main perspectives in Sociology. If you need to review, click here. According to Symbolic Interactionism , deviance is transmitted through socialization in the same way that deviant behavior is learned. For example, an early study revealed that delinquent behavior can be transmitted through play groups & gangs. Today, you will learn about two theories that explain how deviant behavior is learned: Differential Association & Labeling Theory. Both are based on Symbolic Interactionism. Lesson/Activity: How is deviance learned? Differential association theory states that individuals learn deviance in proportion to the number of deviant acts they are exposed to. According to this theory, the more people are exposed to people who break the law, the more apt they are to become criminals. There are three characteristics that affect differential association: 1.The ratio of deviant to nondeviant individuals. A person who knows mostly deviants is more likely to learn deviant behavior. -

Informing the Fraud Triangle: Insights from Differential Association Theory

Informing the Fraud Triangle: Insights from Differential Association Theory Mark Lokanan Ph.D Keywords: Fraud triangle; Differential Association Theory; Accounting; Sub-culture Abstract: The fraud triangle (FT) has been criticized by scholars and practitioners for not being thorough enough to include every occurrence of fraud. However, not every case of fraud can follow the FT and the problem might have been one of interpretation. The purpose of this paper is to lend support to the fraud triangle (FT) by expanding on the understanding of differential 1 association theory (DAT). Sutherland’s work on DAT is a major source to inform our understanding of the FT. The return to his work is intended as a clarification of what Sutherland actually says with respect to the FT and a critical assessment of how far his work can be regarded as being authoritative. To accomplish this task, the paper provides anecdotal evidence from three high-profile accounting fraud cases – Livent, WorldCom, and Enron. The findings reveal that the concepts and propositions of DAT do have the potential to expand our understanding of the FT concepts. DAT seeks to explain the content and process of corporate accounting fraud via sub- culture and specific techniques in which criminal behaviour is learned. Practically, the paper contributes to a wider body of literature that expounds on the value to further develop fraud theories to inform fraud detection and prevention. Introduction During the last two decades, the world was shocked by a series of high profile accounting frauds that sent the accounting profession into turmoil (Clikeman, 2009; Lokanan, 2015). -

Introduction to Sociology 2E Openstax Rice University 6100 Main Street MS-375 Houston, Texas 77005

Introduction to Sociology 2e OpenStax Rice University 6100 Main Street MS-375 Houston, Texas 77005 To learn more about OpenStax, visit http://openstaxcollege.org. Individual print copies and bulk orders can be purchased through our website. © 2015 Rice University. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Under this license, any user of this textbook or the textbook contents herein must provide proper attribution as follows: - If you redistribute this textbook in a digital format (including but not limited to EPUB, PDF, and HTML), then you must retain on every page the following attribution: “Download for free at https://cnx.org/content/col11762/latest/.” - If you redistribute this textbook in a print format, then you must include on every physical page the following attribution: “Download for free at https://cnx.org/content/col11762/latest/.” - If you redistribute part of this textbook, then you must retain in every digital format page view (including but not limited to EPUB, PDF, and HTML) and on every physical printed page the following attribution: “Download for free at https://cnx.org/content/col11762/latest/.” - If you use this textbook as a bibliographic reference, then you should cite it as follows: OpenStax, Introduction to Sociology 2e. OpenStax. 24 April 2015. <https://cnx.org/content/col11762/latest/>. For questions regarding this licensing, please contact [email protected]. Trademarks The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, OpenStax CNX logo, Connexions name, and Connexions logo are not subject to the license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.