Annex I the Problems with Refugee Statistics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UN EBOLA RESPONSE Multi-Partner Trust Fund

UN EBOLA RESPONSE MULTI-PARTNER TRUST FUND The Office of the Special Adviser on the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and Climate Change Multi Partner Trust Fund Office, UNDP http://mptf.undp.org/ebola STEPP Strategy StrateGIC OBJectIVE 1: STOP the outbreak Mission Critical Action 1: Identify and Trace People with Ebola Mission Critical Action 2: Safe and Dignified Burials StrateGIC OBJectIVE 2: TREAT the infected Mission Critical Action 3: Care for Persons with Ebola and Infection Control Mission Critical Action 4: Medical Care for Responders Provision StrateGIC OBJectIVE 3: ENSURE essential services Mission Critical Action 5: Provision of Food Security and Nutrition Mission Critical Action 6: Access to Basic (including non-Ebola Health) Services Mission Critical Action 7: Cash Incentives for Workers Mission Critical Action 8: Recovery and Economy StrateGIC OBJectIVE 4: PRESERVE stability Mission Critical Action 9: Reliable Supplies of Materials and Equipment Mission Critical Action 10: Transport and Fuel Mission Critical Action 11: Social Mobilization and Community Engagement Mission Critical Action 12: Messaging StrateGIC OBJectIVE 5: PREVENT outbreaks Mission Critical Action 13: Preventing Outbreaks Other: Enabling Support to all Objectives RECOVERY Strategy RECOVERY OBJectIVE 1: RS01 Health, Nutrition, and Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) RECOVERY OBJectIVE 2: RS02 Socio-Economic Revitalization RECOVERY OBJectIVE 3: RS03 Basic Services and Infrastructure RECOVERY OBJectIVE 4: RS04 Governance, Peace Building and Social Cohesion -

Sponsorship Programme

Instruction to your Bank or Instruction to your Bank or BuildingBuilding Society to pay by Direct Debit Society to pay byPlease fill Directin the whole form using Debit a ballpoint pen and send it to: Service User NumberService User Number Sean Devereux Children’s Fund SPONSORSHIP 2 9 7 2 9 4 White Picketts Chandler’s Lane For FastPay Ltd Re Sean Devereux Children’s Fund Official Use Only Please fill in the whole form using a ballpointYateley pen and send it to: This is not part of the instruction to your Bank or Building Society Hampshire Dear Customer: Please Complete Below for Our Recordss PROGRAMME Sean Devereux Children’s Fund, White Picketts, GU46 7SR Dear Customer: Please Name: complete below for our records Chandler’s Lane, Yateley, Hampshire GU46 7SR For FastPay Ltd Re Sean Devereux Children’s Fund Official Use Only. Address: Educating African Children This is not part of the instruction to your Bank or Building Society. Name(s) of Account Holder(s): Name(s) of Account Holder(s) Name: Postcode: Phone: Bank or Building Society account number Email: Address: Donation Amount: £ Branch Sort Code Instruction to your Bank or Building Society — — Please pay FastPay Ltd Re Sean Devereux Children’s Fund Direct Debits from the account detailed in this instruction subject to the Name and full postal address of your Bank or safeguardsPostcode: assured by the Direct Debit Guarantee. Bank or Building Society account number: Building Society I understand that this instruction may remain with FastPay Ltd Re Sean Devereux Children’s Fund and, if so, details will be passed electronically to my Bank/Building Society. -

Hart Local Plan (Strategy and Sites) 2032

HART LOCAL PLAN (STRATEGY AND SITES) 2032 Adopted April 2020 Accessible Version HART Local Plan (Strategy and Sites) 2032 Adopted APRIL 2020 Foreword Welcome to our Hart Local Plan (Strategy and Sites) 2032, which has been prepared over several years, reflecting the many and varied views that have been expressed throughout its journey. We are really pleased to have adopted this Plan, to guide new development to the right places, of the right scale with high quality design and with the right supporting infrastructure, while protecting the important parts of our natural and historic environment. Hart is consistently ranked as one of the best places to live in the country, we want to keep it that way. Our overall vision is for Hart to become the best place to live, work and enjoy and this Plan supports the need to balance future development needs with protecting the District’s special qualities. Over the 18 year Plan period to 2032, over 7,000 new homes will be provided, many of which already have planning permission and some have been built. The creation of a new community at Hartland Village is well underway on a previously developed site and this will provide new homes, a new primary school, a neighbourhood centre and extensive open space, whilst ensuring that locally protected sites are not harmed. It is important that this Plan supports the economy, our businesses, and our town and village centres. We are fortunate in Hart to have a wide choice of job options through various small and medium sized businesses, based in one of our many economic sites, through to retail opportunities in our active and vibrant town and village centres. -

Faith in Action Reflection Session

Faith in Action Reflection Session: Social Action – Missionary Disciples This FIA session has been produced by Missio, the Catholic Church’s official charity for overseas mission. Find out more and view our school resources by visiting missio.org.uk Before you begin: Each FIA session must cover at least one key element from ‘The Good News’ and two from ‘The Church Story’. It should also allow participants time to consider their own experience, so that each FIA session models this structure of reflection and prayer. Each FIA session must also conclude with a prayer service. You may wish to have the FIA Session resources available to participants at the beginning of their FIA journey for those who wish to use them as they go along. For this session you will need: • One large candle • An image of Christ or Crucifix • A small globe (optional) • A Missio Red Box & Post-it notes • A4 copies of selected scripture, John 15: 9-17 • Photocopies of Drawing Out Discipleship (Appendix 1) • Photocopies of Cardinal Newman’s Prayer The Mission of My Life (Appendix 2) • I Am Sent Postcards (Appendix 3) Objectives Explore the meaning of mission as a follower of Christ. Understand that, to be a Christian is to be a missionary. Reflect upon the many ways’ individuals are sent to be missionaries of God’s love in the world. Starting point Gather the group together, begin the session with the FIA prayer. Invite participants to share their thoughts and feelings. The following questions may help: • How are you today? (What type of weather best describes how you are feeling?) • How do you think your FIA Award is going so far? • Who or what comes to mind when you hear today’s session theme ‘Missionary Disciple’? 1 Missio 23 Eccleston Square London SW1V 1NU 020 7821 9755 [email protected] missio.co.uk Registered in England and Wales Charity No. -

Me Against My Brother

ME AGAINST MY BROTHER ME AGAINST MY BROTHER AT WAR IN SOMALIA, SUDAN, AND RWANDA A JOURNALIST REPORTS FROM THE BATTLEFIELDS OF AFRICA SCOTT PETERSON Routledge New York London Published in 2000 by Routledge 29 West 35th Street New York, NY 10001 Published in Great Britain by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane London EC4P 4EE This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2002. Copyright © 2000 by Routledge All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data ISBN 0-203-90290-4 Master e-book ISBN ISBN 0-203-90294-7 (Glassbook Format) Portmann, John. When bad things happen to other people / John Portmann. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-415-92334-4 (alk. paper). — ISBN 0-415-92335-2 (pbk.: alk. paper) 1. Suffering—Moral and ethical aspects. 2. Pleasure—Moral and ethical aspects. 3. Sympathy—Moral and ethical aspects. I. Title BJ1409.P67 1999 248.4—dc21 99-26106 CIP For those Africans at war, that their courage and spirit may one day be put to better use building peace; and for Willard S. Crow, my friend, grandfather and traveling companion in China and the Arctic, whose adventures set the precedent CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ix INTRODUCTION xi MAPS xxiii PART I SOMALIA: Warlords Triumphant 1 LAWS OF WAR -

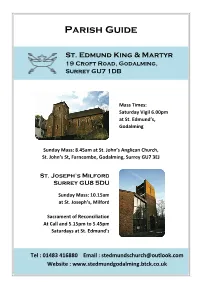

Parish Guide

Parish Guide St. Edmund King & Martyr 19 Croft Road, Godalming, Surrey GU7 1DB Mass Times: Saturday Vigil 6.00pm at St. Edmund’s, Godalming Sunday Mass: 8.45am at St. John’s AngliCan ChurCh, St. John’s St, Farncombe, Godalming, Surrey GU7 3EJ St. Joseph’s Milford Surrey GU8 5DU Sunday Mass: 10.15am at St. Joseph’s, Milford Sacrament of Reconciliation At Call and 5.15pm to 5.45pm Saturdays at St. Edmund’s Tel : 01483 416880 Email : [email protected] Website : www.stedmundgodalming.btCk.Co.uk1 The Parish Vision "Proclaiming Christ to the world : empowering all around us with the presence and joy of the Holy Spirit." In order that the Gospel may be lived in our lives through the Power of the Holy Spirit and our Parish may become a community where all who love Christ Jesus act together to build a better, more human world, we the people of Godalming Parish pledge ourselves that we will become more fully : 1. A Learning ChurCh : Deepening our understanding of faith, humbling ourselves to learn from Our Lord and each other and discovering the true nature of the Body of Christ - open to the Power of the Holy Spirit. 2. A Celebrating ChurCh : Aiming, under the guidance of the Holy Spirit, to deepen and enrich our experience of Prayer and Liturgy, praising Him for His Goodness to us, thanking Him and praying for His help. 3. A Caring Church : Developing a loving, caring and supportive community. 4. A Living Church : Participating in helping the Church become an alive and vibrant force in our Godalming Parish and in the local community; aiming to be Christ in our world, committed to Evangelisation in response to Jesus' commission actively to spread God's truth. -

January 2008

Issue 13 Past Pupils’ Newsletter January 2008 This, our thirteenth issue of a National Newsletter, as usual, is a compilation of the Reports given by Local Associations and other officers on the National Council at our last meeting, which took place at the Salesian School, Battersea, London on 11 November 2007. It also has news about our decision to widen the effect of our Mission support to cover more than just Liberia, as we have done for the last four years; where we provided for Clean water facilities, Electricity generators and Medications to save lives from Malaria and HIV/Aids. We are now moving into Education as our Mission objective for 2007/8 in a number of African countries. Leaving the School Chapel after Mass, shared with the Battersea Old Boys Association, to attend their Memorial Service at the Ambulacrum for Battersea Old Boys and others lost in the two world wars. Father John Dickson SDB, Battersea Rector, leading the Memorial Service at the Ambulacrum. Father Sean Murray, our National Delegate, is to Father John’s right. 1 Issue 13 Past Pupils’ Newsletter January 2008 Nick Potter, Battersea Presi- dent, with Susan Cook from Florida and E J McCarthy, known as Mac. Some of the crowd paying their re- spects to fallen heroes from Batter- sea Past Pupils and others. Fr. Sean was invited to open our meeting with a prayer. Patrick Morrissey, National President, thanked everyone for coming at 0900 to allow National Council members to join with the Battersea Old Salesians Association for their annual Remembrance Mass at 1100. -

SALESIAN NEWSLETTER Issue 9

SALESIAN NEWSLETTER Issue 9 Salesian Newsletter June 2018 THE FAMILY OF DON BOSCO WWW.SALESIAN.SURREY.SCH.UK FINDING THE BALANCE Annie, Year 12 French exchange and the In a Catholic school we believe that we're all by Ben McCann, Assistant Headteacher Maths PGL trip… This is on top of all of the part of the same family. The challenge is to sport that is part of our regular extra- then ingrain this in the children and impress curricular timetable. Do encourage your upon them how important it is that they treat Since the last newsletter, pupils in Year 11 and children to get or make a note to sign up to a everyone they meet in the wider world in the 13 have been working their socks off getting next year if they have missed the sign up this future, as a family member. We can't build the through their examinations. Each exam time round. There is nothing lost in trying Kingdom if the family is divided! completed brings them one-step closer to a something new, tell them to be brave! Our Reflections for this week community grows stronger through shared well-deserved restful summer holiday and What are my family rules and experiences. excellent qualification results in August. expectations? Whilst the GCSE’s are nearly complete and As an England supporter who has drawn Who do I apply them to? the A-Level pupils only have two weeks to go, Australia in the staff sweepstake, I am not Who else could / should I apply them to? sure if the results in the World Cup will live up the rest of the school continue to work hard What are the expectations of me as a to my high expectations! Worst-case right up until the summer holiday. -

National Newsletter - Salesian Past Pupils (Great Britain) - National President: Patrick Morrissey

National Newsletter - Salesian Past Pupils (Great Britain) - National President: Patrick Morrissey Issue No 2 August 2002 This, our second issue of a National 6) After further study of the forms I Newsletter is a compilation of the hope to be able to find a few new Reports made by the Local recruits for our committee in particular Associations to our last National I have in mind the post of Internet Council meeting, which took place at officer from this group. Battersea. We have added some colour to the report by introducing colour 7) Perhaps National Council members photographs throughout the Newsletter might consider it worthwhile using this - you may spot some people you know. data as the start of an over all UK We hope you like this issue and find it database to be held centrally. interesting. Late lunch in The Castle in Battersea High Street, 8) We will produce a summary of the after the meeting. Battersea Old Boys will know it If you have any small or large Salesian well!!! results to go towards our goal of Past Pupil events that you would like identifying exactly what our youngest included in our Newsletter, if you asking for them to be posted back so I members feel they want and perhaps Email me a short description together enlisted the help of the staff in the also fine tuning the form itself. with colour photos I will happily College and I could not have carried include them in future issues. out this exercise without the full co- POSTER IN SALESIAN SOCIAL operation of the Headmaster and the CLUB AT EWELL ê BATTERSEA ASSOCIATION Head of Year 11, Kevin Regan, who happily is a past pupil. -

Yateley, Darby Green & Frogmore

Yateley, Darby Green & Frogmore Neighbourhood Plan 2020 – 2032 VERSION 1.4.2 MAY 2021 PRE SUBMISSION PLPreAN -submission version May 2021 FOREWORD This draft version of the Yateley, Darby Green and Frogmore Neighbourhood Plan represents the culmination of nearly four years work by a group of dedicated volunteers within our three small towns to pull together a plan that represents the broader community’s aspirations for our neighbourhood. Our parish is fortunate in many respects. We live in the least deprived district in the country; we often come out either top or near the top in surveys of the best places to live; there is a vibrant and active community encompassing sports and leisure clubs, churches and events such as the Gig on the Green and the May Fayre; we are surrounded by beautiful countryside with plenty of opportunities for walking, cycling and other leisure activities. At the same time, the town has been quite extensively developed over the past few decades, with the result that there are few places left for further building. In the Local Plan adopted by Hart District Council in April 2020, there are no sites allocated for development in Yateley, and in recognition of that fact, this Neighbourhood Plan does not identify any specific sites. Instead we have concentrated on the key principles and policies that we would want to see adopted when considering any future potential development of our community. We set out early on to establish our strategic objectives for our community, which are summed up in four key themes: to be Happy, Attractive, Sustainable and Inclusive. -

International Law, Arms Embargoes and the United Nations Security Council

Durham E-Theses International law, Arms embargoes and the United Nations security council Everett, Katharine Laura Ann How to cite: Everett, Katharine Laura Ann (2007) International law, Arms embargoes and the United Nations security council, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/2881/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 INTERNATIONAL LAW, ARMS EMBARGOES AND THE UNITED NATIONS SECURITY COUNCIL The copyright of this thesis rests with the author or the university to which it was submitted. No quotation from it, or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author or university, and any information derived from it should be acknowledged. Thesis submitted in fulfilmen t of the requirements for the degree of Master of Jurisprudence Katharine Laura Ann Everett Department of Law, Durham University May 2007 1 2 FEB 2008 In memory of Mr. -

St. Patrick's Primary School

St. Patrick’s Primary School Newsletter Learn from Jesus, Love like Jesus, Live like Jesus 9th June 2017 Summer 2 From the Headteacher School Diary Dear Parents, lives today, giving us strength, courage and resilience. These gifts 13/06/17 3.30pm Y5 Parents meeting Welcome back to school - I hope you will help to sustain us amid the recent enjoyed the half term break and terrorist attacks—our thoughts and 13/06/17 7pm New Parents made the most of the good weather! prayers are with the victims and their Evening families. 16/06/17 2.30pm Y4 Assembly, open Liturgically speaking, summertime afternoon and begins with the marvellous Pentecost Thank you for your continued support story from the Acts of the Apostles. and encouragement. teatime A blast of the spirit’s fire and wind 20/06/17 Orange Mufti Day sends the disciples outdoors into the Mrs P Dix light, freeing them from their fears. 21/06/17 Y5 All Hallows TCI The Holy Spirit is still at work in our Day 22/06/17 PM SVP Mass Staff Changes As usual at this time of the year, staffing is bring planned for September and I am now in a position to make you aware of changes. After 12 years associated with St Patrick’s Mrs Murray will be leaving us as she steps back from class teaching to pursue other avenues in life. We hope she will keep in touch and join us from time to time as a supply teacher. After 2 years at St Patrick’s Miss Pitts will be leaving us to join a school nearer to home, following her house move last year.