Temporary Protection As an Instrument for Implementing the Right of Return for Palestinian Refugees

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Israel by Sydney Fisher

R EVIEW D IGEST: H UMAN R IGHTS & T HE W AR ON T ERROR Israel by Sydney Fisher Israel and Palestine have been in an “interim period” between full scale occupation and a negotiated end to the conflict for a long time. This supposedly intermediate period in the conflict has seen no respite from violations of Palestinians’ human rights or the suicide bombings affecting Israelis. This section will provide resources spanning the issues regarding Israel, Palestine and how the human rights dimensions of this conflict interact with the war on terror. The issue of how both sides will arrive at peace remains a mystery. Background Marek Arnaud. 2003. “The Israeli-Palestinian Conflict: Is There a Way Out?” Australian Journal of International Affairs. 57(2): 243. ABSTRACT: States that the blame for the inability to put an end to the conflict between Israel and the Palestinians must be shared by all parties. Discusses issues of trust and U.S. involvement under both Bill Clinton and George W. Bush. Joel Beinin. 2003. “Is Terrorism a Useful Term in Understanding the Middle East and the Palestinian-Israeli Conflict?” Radical History Review. 12. ABSTRACT: Examines the definition of the term “terrorism” in the context of the Middle East and the Palestinian-Israeli conflict. Politically motivated violence directed against civilian populations and atrocities committed in the course of repressing anticolonial rebellions. Shlomo Hasson. 1996. “Local Politics and Split Citizenship in Jerusalem.” International Journal of Urban & Regional Research. 20(1): 116. ABSTRACT: Explores the relationship between ethno-national conflict, local politics and citizenship rights in Jerusalem. -

Briefing: Labor Zionism and the Histadrut

Briefing: Labor Zionism and the Histadrut International Jewish Anti-Zionist Network-Labor, & Labor for Palestine (US), April 13, 2010 We are thus asking the international trade unions to Jewish working class in any country of the boycott the Histadrut to pressure it to guarantee Diaspora.‖6 rights for our workers and to pressure the The socialist movement in Russia, where most government to end the occupation and to recognize Jews lived, was implacably opposed to Zionism, the full rights of the Palestinian people. ―Palestinian which pandered to the very Tsarist officials who Unions call for Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions,‖ sponsored anti-Semitic pogroms. Similarly, in the February 11, 2007.1 United States, ―[p]overty pushed [Jewish] workers We must call for the isolation of Histadrut, Israel’s into unions organized by the revolutionary minority,‖ racist trade union, which supports unconditionally and ―[a]t its prime, the Jewish labor movement the occupation of Palestine and the inhumane loathed Zionism,‖7 which conspicuously abstained treatment of the Arab workers in Israel. COSATU, from fighting for immigrant workers‘ rights. June 24-26, 2009.2 • Anti-Bolshevism. It was partly to reverse this • Overview. In their call for Boycott, Divestment Jewish working class hostility to Zionism that, on 2 and Sanctions (BDS) against Apartheid Israel, all November 1917, Britain issued the Balfour Palestinian trade union bodies have specifically Declaration, which promised a ―Jewish National targeted the Histadrut, the Zionist labor federation. Home‖ in Palestine. As discussed below, this is because the Histadrut The British government was particularly anxious has used its image as a ―progressive‖ institution to to weaken Jewish support for the Bolsheviks, who spearhead—and whitewash—racism, apartheid, vowed to take Russia, a key British ally, out of the dispossession and ethnic cleansing against the war. -

CONCEPT of STATEHOOD in UNITED NATIONS PRACTICE * ROSALYN COHEN T

1961] THE CONCEPT OF STATEHOOD IN UNITED NATIONS PRACTICE * ROSALYN COHEN t The topic of "statehood under international law" has long been a favorite with jurists. The problem of what constitutes a "state" has been extensively examined and discussed, but all too often in absolutist terms confined to drawing up lists of criteria which must be met before an entity may be deemed a "state." The very rigidity of this approach implies that the term "state" has a fixed meaning which provides an unambiguous yardstick for measuring without serious fear of error, the existence of international personality. The framework of examination being thus constricted, traditional inquiry has endeavored to meet some of its inadequacies by ancillary discussions on the possi- bility of a "dependent state" in international law, of the desirability of universality in certain organizations set up by the international com- munity, and of the rights of peoples to national self-determination. It would appear, however, that these questions, far from being ancillary, are integral to any discussion of "statehood." Even the language of the law-or perhaps especially the language of the law-contains ambiguities which are inherent in any language system, and the diffi- culties presented by this fact can only be resolved by an analysis which takes full cognizance of the contextual background. Thus, when ex- amining what is meant by the word "state," an appraisal of the com- munity interests which will be affected by the decision to interpret it in one way rather than in another is necessary. Discussions, for example, of whether a "dependent state" can exist under international law become meaningless unless there is first an examination of whether the community of nations would find it appropriate, in the light of its long range objectives, to afford the rights which follow from "state- hood" to entities fettered by restrictions which impair their independ- ence. -

Israel: Growing Pains at 60

Viewpoints Special Edition Israel: Growing Pains at 60 The Middle East Institute Washington, DC Middle East Institute The mission of the Middle East Institute is to promote knowledge of the Middle East in Amer- ica and strengthen understanding of the United States by the people and governments of the region. For more than 60 years, MEI has dealt with the momentous events in the Middle East — from the birth of the state of Israel to the invasion of Iraq. Today, MEI is a foremost authority on contemporary Middle East issues. It pro- vides a vital forum for honest and open debate that attracts politicians, scholars, government officials, and policy experts from the US, Asia, Europe, and the Middle East. MEI enjoys wide access to political and business leaders in countries throughout the region. Along with information exchanges, facilities for research, objective analysis, and thoughtful commentary, MEI’s programs and publications help counter simplistic notions about the Middle East and America. We are at the forefront of private sector public diplomacy. Viewpoints are another MEI service to audiences interested in learning more about the complexities of issues affecting the Middle East and US rela- tions with the region. To learn more about the Middle East Institute, visit our website at http://www.mideasti.org The maps on pages 96-103 are copyright The Foundation for Middle East Peace. Our thanks to the Foundation for graciously allowing the inclusion of the maps in this publication. Cover photo in the top row, middle is © Tom Spender/IRIN, as is the photo in the bottom row, extreme left. -

• International Court of Justice • • • • •

• • • INTERNATIONAL COURT OF JUSTICE • • • • • . Request for an • Advisory Opinion on the • Legal Consequences of the • Construction of a Wall • in the Occupied Palestinian Territories • • WRITTEN STATEMENT SUBMITTED BY • THE HASHEMITE KINGDOM OF JORDAN • • • • 30 January 2004 • • • • • TABLE OF CONTENTS • 1. Introduction • Il. General background • III. Immediate background • IV. Relevant facts V. Relevant legal considerations • (a) The Court' s jurisdiction • (i) The request raises a legal question which the Court has jurisdiction ta answer • (ii) There are no compelling reasons which should lead the • Court ta refuse ta give the advisory opinion requested of it. • (b) Applicable legal principles (i) The prohibition of the use of force, and the right of seIf- • determination, are Iules of ius cogens (ii) The territory in whîch the wall has been or is planned to be • constructed constitutes occupied territory for purposes of international law • (lii) The law applicable in respect of occupied territory limîts • the occupying State's power$ (iv) Occupied territory cannot be annexed by the occupying • State • (c) Applicable legal principles and the construction of the wall (i) The occupying State does not have the right effectively to • alIDex occupied territory or otherwise to alter its status (ii) The occupying State does not have the right to alter the • population balance in the occupîed territory by estabIishing alien • settlements • ->- :.• 1 1. • -11- (iii) The occupying State lS not entitled in occupied territory to construct a wall -

By Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Of

FROM DIWAN TO PALACE: JORDANIAN TRIBAL POLITICS AND ELECTIONS by LAURA C. WEIR Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation Adviser: Dr. Pete Moore Department of Political Science CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY January, 2013 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of Laura Weir candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy degree *. Pete Moore, Ph.D (chair of the committee) Vincent E. McHale, Ph.D. Kelly McMann, Ph.D. Neda Zawahri, Ph.D. (date) October 19, 2012 *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables v List of Maps and Illustrations viii List of Abbreviations x CHAPTERS 1. RESEARCH PUZZLE AND QUESTIONS Introduction 1 Literature Review 6 Tribal Politics and Elections 11 Case Study 21 Potential Challenges of the Study 30 Conclusion 35 2. THE HISTORY OF THE JORDANIAN ―STATE IN SOCIETY‖ Introduction 38 The First Wave: Early Development, pre-1921 40 The Second Wave: The Arab Revolt and the British, 1921-1946 46 The Third Wave: Ideological and Regional Threats, 1946-1967 56 The Fourth Wave: The 1967 War and Black September, 1967-1970 61 Conclusion 66 3. SCARCE RESOURCES: THE STATE, TRIBAL POLITICS, AND OPPOSITION GROUPS Introduction 68 How Tribal Politics Work 71 State Institutions 81 iii Good Governance Challenges 92 Guests in Our Country: The Palestinian Jordanians 101 4. THREATS AND OPPORTUNITIES: FAILURE OF POLITICAL PARTIES AND THE RISE OF TRIBAL POLITICS Introduction 118 Political Threats and Opportunities, 1921-1970 125 The Political Significance of Black September 139 Tribes and Parties, 1989-2007 141 The Muslim Brotherhood 146 Conclusion 152 5. -

Duncan Kennedy, Harvard Law School, Israel/Palestine Legal Issues, Fall 2007

Is pal full syll 11/07/07 Seminar Israel/Palestine Legal Issues Syllabus Duncan Kennedy Course Summary Class 1: Historical background up to 1949 Part one: Inside Israel Class 2: The legalities of the appropriation of Palestinian land Class 3: The public law structure of the Israeli polity: “Jewish and democratic” Class 4: The issue of discrimination against the Arab minority Part two: The West Bank and Gaza Class 5: Legal status of the occupation of the West Bank and Gaza, and of Israeli settlements Class 6: The issue of the duties of the occupier with respect to social and economic development: before Oslo and after Oslo Class 7: Are the settlements occupation or de facto annexation? Class 8: Palestinian resistance: the legality or not of violence in response to occupation Class 9: The targets and techniques of armed resistance: the issue of Palestinian violations of international humanitarian law Class 10: The legality or not of Israeli responses to Palestinian resistance Part Three: Legal dimensions of deal breaking issues Class 11: Sovereighty: The status of Jerusalem and the binational state proposal Class 12: The right of return as a legal issue Class 1: Historical background Historical documents (except for the Fourteen Points, all are from The Israel-Arab Reader (Walter Laqueur & Barry Rubin, eds.)) 1 The Fourteen Points from Wikipedia Sykes-Picot agreement MacMahon letter Balfour Declaration Emir Faisal – Chaim Weizmann agreement League of Nations Mandate for Palestine Israeli Declaration of Independence U.N. Resolutions 194 & 303 Israeli Law of Return Aaron Wolf, Hydropolitics along the Jordan River: Scarce Water and its Impact on the Arab-Israeli Conflict (New York: United Nations University Press, 1995) (background summary) Nur Masalha, The Politics of Denial: Israel and the Palestinian Refugee Problem (London: Pluto Press, 2003), ch. -

What Makes a States: Territory

American University Washington College of Law Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law Articles in Law Reviews & Other Academic Journals Scholarship & Research 2012 What Makes a States: Territory Paul Williams Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/facsch_lawrev Part of the International Law Commons What Makes a State? 449 WHAT MAKES A STATE? TERRITORY By Paul R. Williams* What makes a state? Under the Montevideo Convention, a prospective state must meet four criteria. It must have a territory, with a permanent population, subject to the control of a government, and the capacity to conduct international relations (sovereignty). Of these requirements, territory presents the major obstacle. Although the world has no shortage of groups seeking independence (who would gladly form governments and relations with other states), it does have a shortage of real estate. A new state necessarily takes territory from an existing state. Since existing states make international law, it is no surprise that the law is designed to make it very difficult for a new state to form out of an existing state's territory. Territorial integrity, along with sovereignty and political independence, form the "triumvirate of rights" that states enjoy under international law. From these rights, the notion has emerged that new states can only be formed with the consent of the existing state where the territory lies. The triumvirate of rights has long been the standard lens through which the international community views self-determination and the creation of new states. It has become increasingly clear, however, that rigid adherence to these principles can lengthen conflict and create negative incentives. -

Israel's New Bible of Forestry and the Pursuit of Sustainable Dryland

Israel’s New Bible of Forestry and the Pursuit of Sustainable Dryland Afforestation Alon Tal* Ben Gurion University of the Negev After several decades of dramatic reform in forestry practices, the Keren Kayemeth L’Yisrael (KKL) compiled the new orientation and specific management changes in a comprehensive policy entitled the Forestry Bible. While Israel’s foresters origi- nally planted monoculture “pioneer” pine plantations, the new orientation calls for diverse, indigenous, naturally regenerating woodlands and their rich suite of ecosystem services. Timber production has been downgraded and is not to be a priority for Israel’s dryland forests. Rather, a suite of maximization of ecosystem services with a particular emphasis on recreation and conservation drives much of the present strategy. The article highlights the evolution of Israel’s forestry policies and details the new approach to afforestation and forestry maintenance and its rationale. Key words: Forest, Israel, Keren Kayemeth L’Yisrael, pine trees, oak trees, ecosys- tem services. Restoring the vast natural woodlands destroyed during the past century con- stitutes one of the primary challenges for the world’s environmental community. The most accurate estimates place the total loss of total forest area on the planet since the advent of agriculture eight thousand years ago between forty (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, 2005) and forty-seven percent (Billington et al., 1996). Many countries have begun ambitious afforestation efforts that are starting to slow the net annual total loss of global forestlands (Nambiar, 2005) even as regrettably, old-growth forest destruction continues apace. While international attention tends to focus on tropical and temperate reforesta- tion, dryland areas, that comprise 47% of the planet, are also areas where afforesta- tion is urgently needed. -

Sovereignty, Statehood, Self-Determination, and the Issue of Taiwan Jianming Shen

American University International Law Review Volume 15 | Issue 5 Article 4 2000 Sovereignty, Statehood, Self-Determination, and the Issue of Taiwan Jianming Shen Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/auilr Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Shen, Jianming. "Sovereignty, Statehood, Self-Determination, and the Issue of Taiwan." American University International Law Review 15, no. 5 (2000): 1101-1161, This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in American University International Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SOVEREIGNTY, STATEHOOD, SELF- DETERMINATION, AND THE ISSUE OF TAIWAN JIANMING SHEN* INTRODUCTION ............................................. 1102 I. TAIWAN'S ATTRIBUTES AND THE NATURE OF THE TAIW AN ISSUE .................................... ..... 1104 A. HISTORICAL BASIS FOR CHINA'S SOVEREIGNTY OVER T A VAN ................................................ 1105 B. LEGAL BASES FOR CHINA'S SOVEREIGNTY OVER TAIWAN 1109 1. Historic Title as a Legal Basis ....................... 1109 2. Invalidity of the Shimonoseki Treat ................. 1110 3. Legal Effects of the Cairo/Potsdam Declarations..... 1112 4. The 1951 San Francesco Peace Treat ' ................ 1114 5. The 1952 Peace Treat ,............................... 1116 C. INTERNATIONAL RECOGNITION OF CHINA'S SOVEREIGNTY OVER TAIW AN ........................................... 1117 1. PRC's Continuity of the ROC and Its Legal Effects ... 1117 2. Recognition by 160+ States .......................... 1121 3. Recognition by hternationalOrganizations .......... 1122 4. Significance of the General Recognition Accorded to the P R C ............................................. -

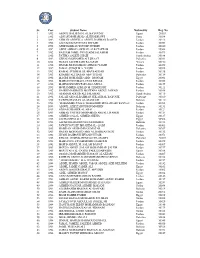

Sr. Year Student Name Nationality Reg. No. 1 1992 ABDUL HALEEM M

Sr. Year Student Name Nationality Reg. No. 1 1992 ABDUL HALEEM M. AL BAYOUMY Egypt 20053 2 1992 ADNAN MOHAMAD AL KHADRAWI Syria 30038 3 1992 AHMAD ABDULLA ABDUL RAHMAN DAOUD Jordan 30213 4 1992 ALI SALEM MUSTAFA DWAIRI Jordan 40051 5 1992 ATEF HABBAS YOUSEF HUSEIN Jordan 40040 6 1992 AWNI AHMAD AWWAD ALFATAFTAH Jordan 20064 7 1992 BASSAM JAMIL SWAILAIM SALAMEH Jordan 40073 8 1992 FATIMA SALEH GHAZI Saudi Arabia 30188 9 1992 GEHAD MOHAMED ALI SHAAT Palestine 30031 10 1992 HASAN SALEH SAID BAJAFAR Yemen 30150 11 1992 ISMAIL MOHAMMAD AHMAD YAGHI Jordan 40059 12 1992 JAMAL SUDQI M.A. YASIN Jordan 30028 13 1992 KAMAL SUBHI M. EL-HAJ BADDAR Jordan 30136 14 1992 KHAMIS ALI HASAN ABU TUHAH Palestine 30134 15 1992 MAGDI MOHAMED ABD - MONAM Egypt 20061 16 1992 MAHMOUD ISMAEL OUDI KHALIL Jordan 40028 17 1992 MAHMOUD MUSTAFA ESA MUSA Jordan 30157 18 1992 MOHAMMED AHMAD M. HAMSHARI Jordan 30111 19 1992 NAJEH MAHMOUD MOSTAFA ABDUL JAWAD Jordan 30058 20 1992 OSAMAH ADEEB ALI SALAMAH Saudi Arabia 30119 21 1992 SALAH ABD ALRAHMAN SHLASH AL BAYOUK Palestine 30010 22 1992 TAWFIQ HASSAN AL-MASKATI Bahrain 30110 23 1993 "MOHAMMED JUMA'A" MOHAMMED HUSSAIN ABU RAYYAN Jordan 40058 24 1993 ABDUL-AZIZ ZAINUDDIN MOHSIN Bahrain 30131 25 1993 ADNAN SHAHER AL'ARAJ Jordan 40121 26 1993 AHMAD YOUSEF MOHAMMD ABDALL HABEH Jordan 40124 27 1993 AHMED GALAL AHMED SHEHA Egypt 20137 28 1993 ALI HASHEM ALI Egypt 30306 29 1993 ALI MOHAMED HUSSN MOHAMED Bahrain 30183 30 1993 FAWZI YOUSEF IBRAHIM AL- QAISI Jordan 40003 31 1993 HAMDAN ALI HAMDAN MATAR Palestine 30267 32 1993 HASAN MOHAMED ABD AL RAHMAN BZEI Jordan 40132 33 1993 HUSNI BAHPOUH HUSAIN UTAIR Jordan 30071 34 1993 KHALIL GUMMA HEMDAN EL-MASRY Palestine 30007 35 1993 MAHMOUD ATYEH MOHD DAHBOUR Jordan 30079 36 1993 MOH'D ABDUL M. -

Legal Implications of Dismantling UNRWA: a European Perspective

Journal of Politics and Law; Vol. 14, No. 3; 2021 ISSN 1913-9047 E-ISSN 1913-9055 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Legal Implications of Dismantling UNRWA: A European Perspective Mais Qandeel1 & Sarah Progin-Theuerkauf2 1 Assistant Professor of international law, School of Law, Örebro University, Sweden 2 Professor, University of Fribourg, Switzerland Received: March 2, 2021 Accepted: April 6, 2021 Online Published: April 6, 2021 doi:10.5539/jpl.v14n3p84 URL: https://doi.org/10.5539/jpl.v14n3p84 Abstract Palestine refugees are excluded from the scope of the international refugee protection system. The agency that is currently protecting them, UNRWA, is under threat. What would the end of UNRWA mean at the European level? This article explains the special situation of Palestinians, the history and role of UNRWA and the consequences that a dissolution of UNRWA would entail. It analyses the situation from an EU perspective, as the CJEU has already delivered several landmark judgments. The article concludes that an abolition of UNRWA would place Palestinians in a better position, as the European Union would be obliged to protect all those persons that currently fall under UNRWA’s mandate and are hence excluded from obtaining refugee status. This is a finding that seems to be totally ignored or at least underestimated by the International Community. Nevertheless, the dissolution of UNRWA might lead to an unprecedented deterioration of the situation of Palestinians living in UNRWA’s operating areas. Keywords: Palestine refugees, EU, ipso facto protection, fundamental rights, EU Qualification Directive, CJEU 1. Introduction In its 2019 Global Trends Report1, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) indicated that, at the end of 2019, almost 79.5 million persons were forcibly displaced worldwide, of which 26 million persons are refugees.2 Of these refugees, 20.4 million persons were under the mandate of UNHCR.