Bringing Back the Palestinian Refugee Question

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Al Jazeera As a Political Tool Within the Contradictions of Qatar

American University in Cairo AUC Knowledge Fountain Theses and Dissertations 6-1-2011 Al Jazeera as a political tool within the contradictions of Qatar Munehiro Anzawa Follow this and additional works at: https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds Recommended Citation APA Citation Anzawa, M. (2011).Al Jazeera as a political tool within the contradictions of Qatar [Master’s thesis, the American University in Cairo]. AUC Knowledge Fountain. https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds/1017 MLA Citation Anzawa, Munehiro. Al Jazeera as a political tool within the contradictions of Qatar. 2011. American University in Cairo, Master's thesis. AUC Knowledge Fountain. https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds/1017 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by AUC Knowledge Fountain. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of AUC Knowledge Fountain. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The American University in Cairo School of Global Affairs and Public Policy Al Jazeera as a Political Tool within the Contradictions of Qatar A Thesis Submitted to the Department of Middle East Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Munehiro Anzawa May 2011 The American University in Cairo School of Global Affairs and Public Policy Al Jazeera as a Political Tool within the Contradictions of Qatar A Thesis Submitted by Munehiro Anzawa to the Department of Middle East Studies May 2011 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts has been approved by Dr. Naila Hamdy _____________________________________________________ Thesis Adviser Affiliation __________________________________________Date_____________ Dr. -

Light at the End of Their Tunnels? Hamas & the Arab

LIGHT AT THE END OF THEIR TUNNELS? HAMAS & THE ARAB UPRISINGS Middle East Report N°129 – 14 August 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... i I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 II. TWO SIDES OF THE ARAB UPRISINGS .................................................................... 1 A. A WEDDING IN CAIRO.................................................................................................................. 2 B. A FUNERAL IN DAMASCUS ........................................................................................................... 5 1. Balancing ..................................................................................................................................... 5 2. Mediation ..................................................................................................................................... 6 3. Confrontation ............................................................................................................................... 7 4. The crossfire................................................................................................................................. 8 5. Competing alliances ................................................................................................................... 10 C. WHAT IMPACT ON HAMAS? ...................................................................................................... -

Al Jazeera, a Classic Example of Soft Power

JOURNALISM EDUCATION IN ASIA-PACIFIC After a century of struggling to earn a NOTED: respected place in the modern univer- sity and lessen the gap between the Dr PHILIP CASS is reviews editor of academy and professionals, journalism Pacific Journalism Review. education has reached a credibility high. Its initial battles have been won. Meanwhile, the turbulence in the Al Jazeera, a industry, incredible pace of technologi- cal change, and threats to freedom of classic example expression present new challenges. When the next volume of this saga is written, journalism education’s first of soft power century expeditionary force will be Intercultural Communication as a credited for providing an auspicious Clash of Civilizations: Al-Jazeera and launching pad for its future. (p. 446). Qatar’s Soft Power, by Tel Samuel-Azran. New York: Peter Lang. 2016. 172 pages. ISBN In her epilogue, Robyn Goodman also 978-1-4331-2264-4 strikes an optimistic note, arguing journalism education has never been ITH the current stand-off bet- as strong, and will have increasing Wween Qatar and Saudi Arabia, relevance in the post-truth era. Brave the United Arab Emirates and their words, and ones us educators will cling allies, Samuel-Azran’s book is ex- to as we face the down the challenges tremely timely. Launched in 1996, Al- of falling student numbers, university Jazeera now broadcasts on multiple administrations bent on leveraging not channels and in four languages at a only ever-higher teaching outputs, but cost of $650 million a year. It reaches also research and ‘engagement’, and an 260 million homes in 130 countries. -

Women and Gender in Middle East Politics

POMEPS STUDIES 19 Women and Gender in Middle East Politics May 10, 2016 Contents Reexamining patriarchy, gender, and Islam Conceptualizing and Measuring Patriarchy: The Importance of Feminist Theory . 8 By Lindsay J. Benstead, Portland State University Rethinking Patriarchy and Kinship in the Arab Gulf States . 13 By Scott Weiner, George Washington University Women’s Rise to Political Office on Behalf of Religious Political Movements . 17 By Mona Tajali, Agnes Scott College Women’s Equality: Constitutions and Revolutions in Egypt . 22 By Ellen McLarney, Duke University Activism and identity Changing the Discourse About Public Sexual Violence in Egyptian Satellite TV . 28 By Vickie Langohr, College of the Holy Cross Egypt, Uprising and Gender Politics: Gendering Bodies/Gendering Space . 31 By Sherine Hafez, University of California, Riverside Women and the Right to Land in Morocco: the Sulaliyyates Movement . 35 By Zakia Salime, Rutgers University The Politics of the Truth and Dignity Commission in Post-Revolutionary Tunisia: Gender Justice as a threat to Democratic transition? . 38 By Hind Ahmed Zaki, University of Washington Women’s political participation in authoritarian regimes First Ladies and the (Re) Definition of the Authoritarian State in Egypt . 42 By Mervat F. Hatem, Howard University Women’s Political Representation and Authoritarianism in the Arab World . 45 By Marwa Shalaby, Rice University The Future of Female Mobilization in Lebanon, Morocco, and Yemen after the Arab Spring . 52 By Carla Beth Abdo, University of Maryland -

The Plight of Palestinian Refugees in Syria in the Camps South of Damascus by Metwaly Abo Naser, with the Support of Ryme Katkhouda and Devorah Hill

Expert Analysis January 2017 Syrian voices on the Syrian conflict: The plight of Palestinian refugees in Syria in the camps south of Damascus By Metwaly Abo Naser, with the support of Ryme Katkhouda and Devorah Hill Introduction: the historical role of Palestinians the Oslo Accords in 1992 and the resulting loss by both the in Syria Palestinian diaspora in general and the inhabitants of the After they took refuge in Syria after the 1948 war, al-Yarmouk refugee camp in particular of their position as Palestinians refugees were treated in the same way as a key source of both material and ideological support for other Syrian citizens. Their numbers eventually reached the Palestinian armed revolution in the diaspora. This was 450,000, living mostly in 11 refugee camps throughout Syria due in part to the failure of the various Palestinian national (UNRWA, 2006). Permitted to fully participate in the liberation factions to identify new ways of engaging the economic and social life of Syrian society, they had the diaspora – including the half million Palestinians living in same civic and economic rights and duties as Syrians, Syria – in the Palestinian struggle for the liberation of the except that they could neither be nominated for political land occupied by Israel. office nor participate in elections. This helped them to feel that they were part of Syrian society, despite their refugee This process happened slowly. After the Israeli blockade of status and active role in the global Palestinian liberation Lebanon in 1982, the Palestinian militant struggle declined. struggle against the Israeli occupation of their homeland. -

Legal Implications of Dismantling UNRWA: a European Perspective

Journal of Politics and Law; Vol. 14, No. 3; 2021 ISSN 1913-9047 E-ISSN 1913-9055 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Legal Implications of Dismantling UNRWA: A European Perspective Mais Qandeel1 & Sarah Progin-Theuerkauf2 1 Assistant Professor of international law, School of Law, Örebro University, Sweden 2 Professor, University of Fribourg, Switzerland Received: March 2, 2021 Accepted: April 6, 2021 Online Published: April 6, 2021 doi:10.5539/jpl.v14n3p84 URL: https://doi.org/10.5539/jpl.v14n3p84 Abstract Palestine refugees are excluded from the scope of the international refugee protection system. The agency that is currently protecting them, UNRWA, is under threat. What would the end of UNRWA mean at the European level? This article explains the special situation of Palestinians, the history and role of UNRWA and the consequences that a dissolution of UNRWA would entail. It analyses the situation from an EU perspective, as the CJEU has already delivered several landmark judgments. The article concludes that an abolition of UNRWA would place Palestinians in a better position, as the European Union would be obliged to protect all those persons that currently fall under UNRWA’s mandate and are hence excluded from obtaining refugee status. This is a finding that seems to be totally ignored or at least underestimated by the International Community. Nevertheless, the dissolution of UNRWA might lead to an unprecedented deterioration of the situation of Palestinians living in UNRWA’s operating areas. Keywords: Palestine refugees, EU, ipso facto protection, fundamental rights, EU Qualification Directive, CJEU 1. Introduction In its 2019 Global Trends Report1, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) indicated that, at the end of 2019, almost 79.5 million persons were forcibly displaced worldwide, of which 26 million persons are refugees.2 Of these refugees, 20.4 million persons were under the mandate of UNHCR. -

Eyewitness Palestine

Nancy Murray In November of last year I co-led an Eyewitness Palestine delegation to the West Bank and Israel – I have made nearly 20 visits to Palestine since my first visit as part of a human rights fact finding delegation in 1988, when the unarmed popular uprising of the entire Palestinian population known as the Intifada was nine months old. Eyewitness Palestine: Moving to the Brink What follows is the text, lightly edited, of a talk on the Eyewitness Palestine Environmental Delegation of Fall 2018, presented at Boston University on March 7th 2019 by Nancy Murray and Hubert Murray. Mariama White-Hammond also How different things are today! In 1988 the small human presented reflecting on her role as a pastor in the African rights delegation I was part of moved around and between a American community committed to civil rights and West Bank and Gaza Strip that had not yet been forcibly environmental justice. She spoke without notes so we are separated from each other, and carved up by walls, ‘Israeli- unable to include her words or the ensuing discussion. only’ roads and hundreds of checkpoints. Israeli settlers 1 numbered a fraction of what they are today. The Israeli army ending Israel’s occupation, which was 20 years old when the and its armored vehicles and tanks were everywhere, and uprising began. And everywhere, we saw evidence of Palestinians were always being stopped to have their ID cards America’s involvement, from the ‘Made in Pennsylvania’ tear checked, but unlike today, it was still possible to drive the gas canisters that caused at least 70 deaths and untold short distance from the West Bank through Israel to the Gaza miscarriages during the course of the Intifada to the ‘Made in Strip, and the Palestinians of the West Bank and Gaza Strip California’ billy clubs used to break demonstrators’ bones. -

The Meaning of Homeland for the Palestinian Diaspora : Revival and Transformation Mohamed Kamel Doraï

The meaning of homeland for the Palestinian diaspora : revival and transformation Mohamed Kamel Doraï To cite this version: Mohamed Kamel Doraï. The meaning of homeland for the Palestinian diaspora : revival and trans- formation. Al-Ali, Nadje Sadig ; Koser, Khalid. New approaches to migration ? : transnational com- munities and the transformation of home, Routledge, pp.87-95, 2002. halshs-00291750 HAL Id: halshs-00291750 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00291750 Submitted on 24 Sep 2013 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. The meaning of homeland for the Palestinian diaspora Revival and transformation Mohamed Kamel Doraï Lost partially in 1948, and complete1y in 1967, the idea of a homeland continues to live in Palestinian social practices and through the construction of a diasporic territory - a symbolic substitute for the lost homeland. This chapter aims to analyse the mechanisms by which the homeland has been perpetuated in exile, and focuses in particular on Palestinian refugee camps and settlements. It shows how a refugee community can partially transform itself into a transnational community, and examines what role the transformation of home plays in this process. After fifty years of exile, Palestinian refugees continue to claim their right to return to their country of origin. -

Ndce-News Issue 9.Pdf

Issue # 9 - 2012 PNGO IV: Mid-Term Review www.ndc.ps rom the 17th to the 29th of benefit most from the mechanism’s F March a joint AFD and World experience. NDC Director, Ghassan Bank delegation carried out a Kasabreh, is pleased that so much detailed mid-term review of the ground was covered during the Palestinian NGO IV Project managed mission: “the recent mid-term review by NDC (funded by AFD/World has given the donors, NDC, partner Bank). The review focused on NGOs and the beneficiaries the chance assessing the progress of the project to take an active role in improving the so far, and considering PNGO IV project. It was heartening to improvements to the delivery of see how committed each stakeholder is PNGO IV. It was an occasion for self to this development initiative, and the -analysis within partner NGOs, wonderful achievements of our inspiring N D C a n d t h e d o n o r s . NGO partners. I am confident that the Consequently, the process provides strategic questions posed during the an opportunity to strengthen mission will only advance the systems of social accountability effectiveness of PNGO IV and the NDC within the PNGO IV project. A mechanism”. NDC looks forward to number of important meetings were the remainder of the PNGO IV also held with a range of PA project motivated by the direct ministries. PNGO IV has proved involvement of partners and r very successful and cooperation with beneficiaries, and the knowledge and e the PA remains essential if the insight of AFD and the World Bank. -

Conversaciones Sobre Oriente Medio Wadah Khanfar

CONVERSACIONES SOBRE ORIENTE MEDIO WADAH KHANFAR Co-founder the Sharq Forum and the former director general of the Al Jazeera Network. He began his career with the network in 1997, covering some of the world's key political zones, including South Africa, Afghanistan and Iraq. He was appointed the chief of the Baghdad bureau, and later as the network's managing director. In 2006, he became Al Jazeera's director general. During his 8-year tenure at the helm, the network transformed from a single channel into a media network including Al Jazeera Arabic, Al Jazeera English, Al Jazeera Documentary and the Al Jazeera Center for Studies. During this period, the Arab world witnessed historic transformation including Arab Awakening. Khanfar, who resigned from the network in September 2011, has been named as one of Foreign Policy's Top 100 global thinkers of 2011 as well as one of Fast Company's 'Most Creative People in Business' of the year. Khanfar has a diverse academic background with post-graduate studies in Philosophy, African Studies, and International Politics. Wadah Khanfar es cofundador del Sharq Forum y ex director general de Al Jazeera. Inició su carrera profesional en la cadena en 1997, cubriendo algunos de los principales escenarios de la política mundial, entre ellos Sudáfrica, Afganistán e Irak. Fue nombrado director de la oficina de Bagdad y, más adelante, director gerente de la red. En 2006, fue designado director general de Al Jazeera. Durante su mandato de 8 años al frente de la misma, Al Jazeera ha pasado de ser un solo canal de noticias a convertirse en una red de medios, integrada por Al Jazeera Arabic, Al Jazeera English, Al Jazeera Documentary y el Centro de Estudios de Al Jazeera. -

POSITION PAPER- Palesinian Refugees

The Question of Palestine in the times of COVID-19: Position paper on the situation for Palestinian refugees in Jordan, Lebanon, occupied Palestine and Syria (No.2) June 2020 This position paper is part of a series that the Global Network of Experts on the Question of Palestine (GNQP) is producing to document the impact of COVID-19 (Coronavirus) on the Question of Palestine, by studying the effect of the pandemic on Palestinian refugees in the region. This brief focuses on Palestinian refugees residing in Jordan, Lebanon, occupied Palestine and Syria. Purpose of the brief approximately 5.6 million are registered The brief shows how the COVID-19 as “Palestine refugees” with the United crisis is affecting Palestinian refugees Nations Relief and Works Agency for in Jordan, Lebanon, occupied Palestine Palestinians in the Near East (UNRWA) in (Gaza Strip and West Bank, including East Jordan, Lebanon, occupied Palestine and 2 Jerusalem) and Syria. Following a general Syria. A smaller number was displaced background, the paper presents: when Israel occupied the Gaza Strip and West Bank, including East Jerusalem · a summary of available regional in 1967; while these are not officially and country-specific facts that registered with UNRWA, some receive its indicate that COVID-19 is aggravating services on humanitarian grounds. Less the humanitarian conditions and than half of these refugees, including vulnerability of Palestinian refugees; their descendants, live in one of the 58 · a brief overview of applicable legal recognized refugee camps, while an obligations toward Palestinian unknown number live in urban and rural refugees; (camp) settings across the region. -

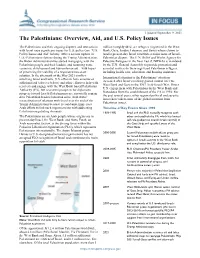

The Palestinians: Overview, 2021 Aid, and U.S. Policy Issues

Updated September 9, 2021 The Palestinians: Overview, Aid, and U.S. Policy Issues The Palestinians and their ongoing disputes and interactions million (roughly 44%) are refugees (registered in the West with Israel raise significant issues for U.S. policy (see “U.S. Bank, Gaza, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria) whose claims to Policy Issues and Aid” below). After a serious rupture in land in present-day Israel constitute a major issue of Israeli- U.S.-Palestinian relations during the Trump Administration, Palestinian dispute. The U.N. Relief and Works Agency for the Biden Administration has started reengaging with the Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) is mandated Palestinian people and their leaders, and resuming some by the U.N. General Assembly to provide protection and economic development and humanitarian aid—with hopes essential services to these registered Palestinian refugees, of preserving the viability of a negotiated two-state including health care, education, and housing assistance. solution. In the aftermath of the May 2021 conflict International attention to the Palestinians’ situation involving Israel and Gaza, U.S. officials have announced additional aid (also see below) and other efforts to help with increased after Israel’s military gained control over the West Bank and Gaza in the 1967 Arab-Israeli War. Direct recovery and engage with the West Bank-based Palestinian U.S. engagement with Palestinians in the West Bank and Authority (PA), but near-term prospects for diplomatic progress toward Israeli-Palestinian peace reportedly remain Gaza dates from the establishment of the PA in 1994. For the past several years, other regional political and security dim.