Alaris Capture Pro Software

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Celebrate in Buckinghamshire

Celebratein Buckinghamshire CIVIL MARRIAGES • CIVIL PARTNERSHIPS • RENEWAL OF VOWS COMMITMENT CEREMONIES • NAMING CEREMONIES • CITIZENSHIP CEREMONIES 1 Welcome Firstly, many congratulations on your www.graciousphotography.com forthcoming celebrations. We are delighted that you have chosen the beautiful and charming county of Buckinghamshire for your ceremony. We have over 80 wonderful licensed venues and four marriage rooms within our Register Offices conveniently located throughout the county offering you great flexibility and choice. This publication has been created to help guide you through the legal formalities and personal choices in planning your special day. Our experienced and professional staff will do everything they can to ensure that your ceremony is everything you would wish it to be and becomes a lasting and wonderful memory for you and your guests. Buckinghamshire Registration Service Published by: Buckinghamshire Registration Service, Buckinghamshire Register Office, County Hall, Aylesbury HP20 1XF 01296 383005 [email protected] www.weddings.buckscc.gov.uk Designed and produced by Crystal Publications Ltd. Reproduction in whole or part is prohibited without the written consent of the publisher. Whilst every care has been taken in compiling this publication, Buckinghamshire County Council and the Registration Service cannot accept responsibility for any inaccuracies, nor guarantee or endorse any of the products or the services advertised. All information is correct at the time of going to print. © 2018 G G Cover -

Buckinghamshire Historic Town Project

Long Crendon Historic Town Assessment Consultation Report 1 Appendix: Chronology & Glossary of Terms 1.1 Chronology (taken from Unlocking Buckinghamshire’s Past Website) For the purposes of this study the period divisions correspond to those used by the Buckinghamshire and Milton Keynes Historic Environment Records. Broad Period Chronology Specific periods 10,000 BC – Palaeolithic Pre 10,000 BC AD 43 Mesolithic 10,000 – 4000 BC Prehistoric Neolithic 4000 – 2350 BC Bronze Age 2350 – 700 BC Iron Age 700 BC – AD 43 AD 43 – AD Roman Expedition by Julius Caesar 55 BC Roman 410 Saxon AD 410 – 1066 First recorded Viking raids AD 789 1066 – 1536 Battle of Hastings – Norman Conquest 1066 Wars of the Roses – Start of Tudor period 1485 Medieval Built Environment: Medieval Pre 1536 1536 – 1800 Dissolution of the Monasteries 1536 and 1539 Civil War 1642-1651 Post Medieval Built Environment: Post Medieval 1536-1850 Built Environment: Later Post Medieval 1700-1850 1800 - Present Victorian Period 1837-1901 World War I 1914-1918 World War II 1939-1945 Cold War 1946-1989 Modern Built Environment: Early Modern 1850-1945 Built Environment: Post War period 1945-1980 Built Environment: Late modern-21st Century Post 1980 1.2 Abbreviations Used BGS British Geological Survey EH English Heritage GIS Geographic Information Systems HER Historic Environment Record OD Ordnance Datum OS Ordnance Survey 1.3 Glossary of Terms Terms Definition Building Assessment of the structure of a building recording Capital Main house of an estate, normally the house in which the owner of the estate lived or Messuage regularly visited Deer Park area of land approximately 120 acres or larger in size that was enclosed either by a wall or more often by an embankment or park pale and were exclusively used for hunting deer. -

For Enquiries on This Agenda Please Contact

Incorporating the parishes of : Ashendon WADDESDON LOCAL AREA FORUM Dorton Edgcott Fleet Marston Grendon Underwood Kingswood DATE: 3 December 2019 Ludgershall TIME: 7.00 pm Marsh Gibbon Nether Winchendon Calvert Green Village Quainton VENUE: Hall Upper Winchendon Waddesdon Westcott Woodham Wotton Underwood PARISH / TOWN COUNCIL DROP-IN FROM 6.30pm Come along to the drop-in and speak to your local representative from Transport for Buckinghamshire who will be on hand to answer your questions. AGENDA Item Page No 1 Apologies for Absence / Changes in Membership 2 Declarations of Interest To disclose any Personal or Disclosable Pecuniary Interests 3 Action Notes 3 - 8 To confirm the notes of the meeting held on 2 October 2019. 4 Question Time There will be a 20 minute period for public questions. Members of the public are encouraged to submit their questions in advance of the meeting to facilitate a full answer on the day of the meeting. Questions sent in advance will be dealt with first and verbal questions after. 5 Petitions None received 6 The Chairmans Update 7 Youth Project Update Update from the Youth Project group. 8 Climate Change Presentation from the Local Area Forum Officer. 9 Transport for Bucks Update 9 - 32 10 Thames Valley Neighbourhood Police Update 11 Street Association Presentation from Ms H Cavill, Street Association Project Manager. Visit democracy.buckscc.gov.uk for councillor information and email alerts for meetings, and decisions affecting your local area. 12 Unitary Update 33 - 38 Update from the Lead Area Officer, BCC. 13 AVDC Update 39 - 46 Update from Mr W Rysdale, AVDC. -

The Loss of Normandy and the Invention of Terre Normannorum, 1204

The loss of Normandy and the invention of Terre Normannorum, 1204 Article Accepted Version Moore, A. K. (2010) The loss of Normandy and the invention of Terre Normannorum, 1204. English Historical Review, 125 (516). pp. 1071-1109. ISSN 0013-8266 doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/ehr/ceq273 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/16623/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . To link to this article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ehr/ceq273 Publisher: Oxford University Press All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online 1 The Loss of Normandy and the Invention of Terre Normannorum, 1204 This is a pre-copy-editing, author-produced PDF of an article accepted for publication in English Historical Review following peer review. The definitive publisher-authenticated version [T. K. Moore, „The Loss of Normandy and the Invention of Terre Normannorum, 1204‟, English Historical Review (2010) CXXV (516): 1071-1109. doi: 10.1093/ehr/ceq273] is available online at: http://ehr.oxfordjournals.org/content/CXXV/516/1071.full.pdf+html Dr. Tony K. Moore, ICMA Centre, Henley Business School, University of Reading, Whiteknights, Reading, RG6 6BA; [email protected] 2 Abstract The conquest of Normandy by Philip Augustus of France effectively ended the „Anglo-Norman‟ realm created in 1066, forcing cross-Channel landholders to choose between their English and their Norman estates. -

List of Fee Account

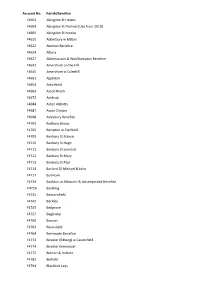

Account No. Parish/Benefice F4603 Abingdon St Helens F4604 Abingdon St Michael (Use from 2019) F4605 Abingdon St Nicolas F4610 Adderbury w Milton F4622 Akeman Benefice F4624 Albury F4627 Aldermaston & Woolhampton Benefice F4642 Amersham on the Hill F4645 Amersham w Coleshill F4651 Appleton F4654 Arborfield F4663 Ascot Heath F4672 Ashbury F4684 Aston Abbotts F4687 Aston Clinton F4698 Aylesbury Benefice F4703 Badbury Group F4705 Bampton w Clanfield F4709 Banbury St Francis F4710 Banbury St Hugh F4711 Banbury St Leonard F4712 Banbury St Mary F4713 Banbury St Paul F4714 Barford SS Michael & John F4717 Barkham F4724 Basildon w Aldworth & Ashampstead Benefice F4726 Baulking F4735 Beaconsfield F4742 Beckley F4745 Bedgrove F4757 Begbroke F4760 Benson F4763 Berinsfield F4764 Bernwode Benefice F4773 Bicester (Edburg) w Caversfield F4774 Bicester Emmanuel F4775 Bierton & Hulcott F4782 Binfield F4794 Blackbird Leys F4797 Bladon F4803 Bledlow w Saunderton & Horsenden F4809 Bletchley F4815 Bloxham Benefice F4821 Bodicote F4836 Bracknell Team Ministry F4843 Bradfield & Stanford Dingley F4845 Bray w Braywood F6479 Britwell F4866 Brize Norton F4872 Broughton F4875 Broughton w North Newington F4881 Buckingham Benefice F4885 Buckland F4888 Bucklebury F4891 Bucknell F4893 Burchetts Green Benefice F4894 Burford Benefice F4897 Burghfield F4900 Burnham F4915 Carterton F4934 Caversham Park F4931 Caversham St Andrew F4928 Caversham Thameside & Mapledurham Benefice F4936 Chalfont St Giles F4939 Chalfont St Peter F4945 Chalgrove w Berrick Salome F4947 Charlbury -

Long Crendon Conservation Area Document

Long Crendon Long Long Crendon Conservation Areas Long Crendon Aerial Photograph by UK Perspectives Designated by the Council 25th February 2009 following public consultation Long Crendon Conservation Areas Long Crendon Conservation Areas Long Crendon Conservation Areas St Mary’s Church page CHAPTER 1 - INTRODUCTION Introduction ................................................................................................................................................ 1 CHAPTER 2 - PLANNING POLICY Planning Policy .......................................................................................................................................... 2 CHAPTER 3 - SUMMARY Summary ...................................................................................................................................................... 4 CHAPTER 4 - LOCATION AND CONTEXT Location ........................................................................................................................................................ 5 Landscape setting ..................................................................................................................................... 6 CHAPTER 5 - GENERAL CHARACTER AND PLAN FORM General character and plan form ....................................................................................................... 8 CHAPTER 6 - HISTORIC DEVELOPMENT AND FORMER USES Origins .......................................................................................................................................................... -

Full Version of AVDLP

AYLESBURY VALE DISTRICT COUNCIL AAyylleessbbuurryy VVaallee DDiissttrriicctt LLooccaall PPllaann WWrriitttteenn SStatatteemmeenntt Part AVJJAANNUUAARRYYD 22000044 LPaPrtII The Aylesbury Vale District Local Plan is published in two parts: Part I - the Written Statement and Conservation Area map insets - and Part II which comprises the Proposals Map. The Written Statement and Proposals Map should be read in conjunction with each other. Part II contains 33 sheets to a scale of 1:20,000 covering the whole District - where necessary insets to a larger scale are included to show details clearly. It includes insets for Aylesbury, Buckingham, Haddenham, Wendover & Winslow on two loose sheets. Norman Skedge Director Department of Environment and Planning Friars Square Offices 4 Great Western Street Aylesbury Bucks HP20 2TW JANUARY 2004 Tel: 01296 585439 Fax: 01296 398665 Minicom: 01296 585055 DX: 4130 Aylesbury E-mail: [email protected] AVDLPForeword FOREWORD We live in times of constant change. This Development Plan, the most important yet produced for our District, reflects - even anticipates - change in a way that earlier plans did not come close to doing. Yet the Council's corporate mission - to make Aylesbury Vale the best possible place for people to live and work - remains a timeless guiding principle. So comprehensive is this District Local Plan for Aylesbury Vale that it will affect the lives of people over the next seven years to 2011. There are two main themes: sustainability and accessibility. Sustainability, in its purest sense, requires us to take no more from the environment than we put back. The Council has striven to minimise consumption of natural resources by looking carefully at the demands development makes on land, air and water, and its impact on the natural and historical environment. -

Archive Catalogue

Buckinghamshire Archaeological Society CATALOGUE OF THE SOCIETY'S COLLECTION OF ARCHIVES HELD IN THE MUNIMENT ROOM Compiled by Lorna M. Head With additional material by Diana Gulland Buckinghamshire Papers No.1 2002 additions and amendments 2007 HOW TO USE THE CATALOGUE These archives may be consulted, on application to Mrs. Diana Gulland, the Hon. LibrarianIArchivist, on Wednesdays from 10.00am to 4.00pm. When requesting material please quote the call mark, found on the left-hand side of the page, together with the full description of the item. General e nquiries about the archives, or requests for more details of those collections which are listed as having been entered on to the Library's database, are welcomed either by letter or telephone. This Catalogue describes the archives in the Muniment Room at the time of printing in 2002. Details of additions to the stock and of progress in entering all stock on to the Society's computer database will be posted on our proposed website and published in our Newsletters. Buckinghamshire Archaeological Society Library County Museum Church Street Aylesbury Bucks HP20 2QP Telephone No. 01296 678114 (Wednesdays only) CONTENTS Call mark Page Introduction 3 Antiquarian collections Warren R. DAWSON DAW Gerald and Elizabeth ELVEY ELVEY Henry GOUGH and W. P. Storer GOU F. G. GURNEY GUR R. W. HOLT HOL Rev. H. E. RUDDY RUD A. V. WOODMAN WOO Dr Gordon H. WYATT WYA Other collections ELECTION MATERIAL ELECT George LIPSCOMB'S notes for The History and Antiquities of the County of Buckingham L1 P Copies of MANUSCRIPTS MSS MAPS MAPS MISCELLANEOUS COLLECTION MISC POLL BOOKS and ELECTION REGISTERS POLL Topographical PRINTS PRINTS Parish REGISTER transcripts REG SALE CATALOGUES SAL INTRODUCTION, by Lorna Head For many years after its foundation in 1847, the Buckinghamshire Archaeological Society was the only repository for archives in the county and a collection was gradually built up through deposits and gifts. -

MIDSOMER MURDERS TRAIL Follow Filming Locations in and Around the Historic Market Town of Thame

THAME TRAIL INSIDE GUIDED TOURS AVAILABLE THAME OXFORDSHIRE MIDSOMER MURDERS TRAIL Follow filming locations in and around the historic market town of Thame visitmidsomer.com thametowncouncil.gov.uk THAME AND ITS MIDSOMER MURDERS FILMING LOCATIONS MIDSOMER WALKING TRAIL There have now been well over 100 episodes. John Nettles played DCI Barnaby for the first 81 episodes, stepping down in OF THAME TOWN CENTRE 2011 at the end of series 13. Neil Dudgeon has played Barnaby Midsomer Murders is based on the novels of Caroline ever since. Thame has featured in 16 episodes, in some briefly Graham. The original pilot programme, The Killings at Badgers but in others, such as Picture of Innocence and Vixen’s Run, it Drift, was aired on 23rd March 1997 and the four episodes of features heavily. Episode 1, series 20, screened in 2019, features the first full series in 1998, Written in Blood, Death of a Hollow the gatehouse of Thame’s Prebendal and nearby cricket ground. Man, Faithful Unto Death and Death in Disguise, were based on her books. Elizabeth Spriggs was a leading actor in the first The walking trail takes just over an hour and features all the episode and is buried in St Mary’s Churchyard, Thame. locations used in the town centre. The suggested starting point is Thame Museum. THAME MUSEUM THAME TOWN HALL BUTTERMARKET THE COFFEE HOUSE MARKET HOUSE RUMSEY’S CHOCOLATERIE THE SWAN HOTEL 1 THAME MUSEUM 4 TIM RUSS & COMPANY 7 PRETTY LIKE PICTURES The Museum was used for the interior scenes at Causton In The House in the Woods Tim Russ & Company, Estate Agents, At the top of Buttermarket, Pretty Like Pictures appears in Museum in Secrets and Spies. -

Records Buckinghamshire

VOL. XI.—No. 7. RECORDS OF BUCKINGHAMSHIRE BEING THE JOURNAL OF THE Architectural and Archaeological Society FOR THE County of Buckingham (Founded Nov. 16, 1847.) Contents. Excavation at Danesborough Camp. The Building of Winslow Hall. By By SIB JAHES BERRY. THE EDITOR. Reviews of Books. The Royal Arms in Churches. By Notes WILLIAM BRADBROOKE. j obituary Extents of the Royal Manors of ! Excersion and Annual Meeting. Aylesbury and Brill, CIRCA 1155. ; Additions to Museum. By G. HERBERT FOWLER. ! Index to VOL. XI. PUBLISHED FOR THE SOCIETY. AYLESBURY: G. T. DE FRAINE & CO., LTD., " BUCKS HERALD" OFFICE. 1926. PRICES of "RECORDS OF BUCKS" Obtainable from The Curator, Bucks County Museum, Aylesbury Vol. Out of Print. Odd Parts. Complete Volume. I. 2,3, 4, 6, 7,8. 1,5 4/- each None ib o offer II. 1 •2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7,8 ... 4/- „ Not sold separately III. 1 to 8 4/- „ £1 1 0 IV. ! 1 to 8 4/- „ £1 1 0 V. 5,6,8. 1,2,3,4,7 4/- „ Not sold separately VI. , 2 1, 3,4, 5 ... 4/- „ £1 1 0 VII. 1 to 6 3/- „ 15 0 VIII. 1 to 6 3/- „ 15 0 IX. 1 to 6 3/- „ 15 0 X. ... 1 to 7 3/- „ 15 0 XI. 2 ... | 1,3,4,5,6 4/- „ i A Set from Vol, II. to Vol. X. complete £8 5s. 25 per Gent. reduction to Members of the Society. In all cases Postage extra. PARISH REGISTERS. Most of the Registers which have been printed can be obtained of the Curator. -

Stained Glass from Notley Abbeyl

Stained Glass from Notley Abbeyl By ST. J. o. GAMLEN N the summer of 1937 the Oxford University Archaeological Society carried I out excavations on the site of Notley Abbey on the borders of Buckingham shire and Oxfordshire two or three miles NW. of Thame, in the parish of Long Crendon, Bucks. The main objective of the Society was to ascertain the plan ofthe abbey church. The abbot's house and part ofthe claustral buildings were the only structures above ground. The plan of the cloister itself and the entrance from it into the church were known. In 1932-3 the site of the chapter-house and slype had been excavated by Mr. C. Hohler. There was ' no further information on the site and practically no documentary evidence apart from the foundation charter. The work was restricted by shortage of time and workers. There was, however, a still greater handicap in the fact that about fifty years before, the farmer who then owned the site dug up nearly all the ashlar on the site to make foundations for a new road which he wished to construct. Instead, therefore, of a complete uncovering of the whole area, it was only possible to dig trenches at likely points at right angles to the expected line of wall or arcade in order to cut across the trenches which had been made to grub up the foundations for the road and then been filled in with material sufficiently different from the adjoining soil for the robber trench to be detected. In spite of these difficulties, the plan of the church was ascertained and the chief aim of the work achieved. -

MEDIEVAL PA VINGTILES in BUCKINGHAM SHIRE LTS'l's F J

99 MEDIEVAL PAVINGTILES IN BUCKINGHAM SHIRE By CHRISTOPHER HOHLE.R ( c ncluded). LT S'l'S F J ESI NS. (Where illuslratio ns of the designs were given m the last issue of the R rt•ord.t, Lit e umnlJ er o f the page where they will LJc found is give11 in tl te margi n). LIST I. TILES FROM ELSEWHERE, NOW PRESERVED IN BUCKINGHAM SHIRE S/1 Circular tile representing Duke Morgan (fragment). Shurlock no. 10. Little Kimble church. S/2 Circular tile representing Tnstan slaying Morhaut. Shurlock no. 13. Little Kimble church. S/3 Circular tile representing Tristan attacking (a dragon). Shurlock no. 17. Little Kimble church. S/4 Circular tile representing Garmon accepting the gage. Shurlock no. 21. Little Kimble church. S/5 Circular tile representing Tristan's father receiving a message. Shurlock no. 32. Little Kimble church. S/6 Border tile with grotesques. Shurlock no. 39. Little Kimble church. S/7 Border tile with inscription: + E :SAS :GOVERNAIL. Little Kimble church (fragment also from "The Vine," Little Kimble). S/8 Wall-tiles (fragmentary) representing an archbishop, a queen, S/9 and a king trampling on their foes. S/10 Shurlock frontispiece. Little Kimble church (fragment of S/10 from "The Vine"). Nos. S/1-10 all from Ohertsey Abbey, Surrey ( ?). S/11 Border tile representing a squirrel. Wilts. Arch. Mag. vol. XXXVIII. Bucks Museum, Aylesbury, as from Bletchley. No. S/11 is presumably from Malmesbury Abbey. LIST II. "LATE WESSEX" TILES in BUCKINGHAMSHIRE p. 43 W /1 The Royal. arms in a circle. Bucks.