Diversity Outreach in Major League Baseball: a Stakeholder Approach

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Checklist 19TCUB VERSION1.Xls

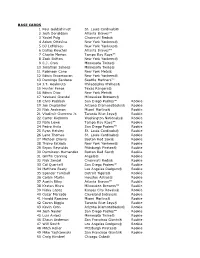

BASE CARDS 1 Paul Goldschmidt St. Louis Cardinals® 2 Josh Donaldson Atlanta Braves™ 3 Yasiel Puig Cincinnati Reds® 4 Adam Ottavino New York Yankees® 5 DJ LeMahieu New York Yankees® 6 Dallas Keuchel Atlanta Braves™ 7 Charlie Morton Tampa Bay Rays™ 8 Zack Britton New York Yankees® 9 C.J. Cron Minnesota Twins® 10 Jonathan Schoop Minnesota Twins® 11 Robinson Cano New York Mets® 12 Edwin Encarnacion New York Yankees® 13 Domingo Santana Seattle Mariners™ 14 J.T. Realmuto Philadelphia Phillies® 15 Hunter Pence Texas Rangers® 16 Edwin Diaz New York Mets® 17 Yasmani Grandal Milwaukee Brewers® 18 Chris Paddack San Diego Padres™ Rookie 19 Jon Duplantier Arizona Diamondbacks® Rookie 20 Nick Anderson Miami Marlins® Rookie 21 Vladimir Guerrero Jr. Toronto Blue Jays® Rookie 22 Carter Kieboom Washington Nationals® Rookie 23 Nate Lowe Tampa Bay Rays™ Rookie 24 Pedro Avila San Diego Padres™ Rookie 25 Ryan Helsley St. Louis Cardinals® Rookie 26 Lane Thomas St. Louis Cardinals® Rookie 27 Michael Chavis Boston Red Sox® Rookie 28 Thairo Estrada New York Yankees® Rookie 29 Bryan Reynolds Pittsburgh Pirates® Rookie 30 Darwinzon Hernandez Boston Red Sox® Rookie 31 Griffin Canning Angels® Rookie 32 Nick Senzel Cincinnati Reds® Rookie 33 Cal Quantrill San Diego Padres™ Rookie 34 Matthew Beaty Los Angeles Dodgers® Rookie 35 Spencer Turnbull Detroit Tigers® Rookie 36 Corbin Martin Houston Astros® Rookie 37 Austin Riley Atlanta Braves™ Rookie 38 Keston Hiura Milwaukee Brewers™ Rookie 39 Nicky Lopez Kansas City Royals® Rookie 40 Oscar Mercado Cleveland Indians® Rookie -

UPCOMING GAMES and PROBABLE STARTERS Richmond Flying Squirrels

Richmond Flying Squirrels (SFG) (12-7) vs. Hartford Yard Goats (COL) (9-10) LHP Garrett Williams (1-0, 5.56 ERA) vs RHP Peter Lambert (1-1, 1.69 ERA) Friday, April 27th- 7:05 P.M. The Diamond, Richmond VA Game # 20 : (12-7) Home Game #8 : (6-1) Radio: Fox Sports 910 (6:35 P.M.) Internet: FoxSportsRichmond.com UPCOMING GAMES AND PROBABLE STARTERS Saturday, April 28th vs Hartford Yard Goats: RHP Cory Taylor (2-1, 4.96 ERA) vs RHP Parker French (0-2, 8.59 ERA) First Pitch 6:00 P.M. Sunday, April 29th vs Hartford Yard Goats: RHP Shaun Anderson (3-1, 2.86 ERA) vs LHP Jack Wynkoop (0-1, 4.20 ERA) First Pitch 1:05 P.M. Monday, April 30th vs Altoona Curve: TBD vs RHP J.T. Brubaker (1-1, 1.57 ERA) First Pitch 6:35 P.M. Squirrels Drop First Series of 2018: + The Flying Squirrels lost their first series of the 2018 season on Wednesday against the Bowie Baysox. Until the Baysox series, the Squirrels had won their past four series in a row (Hartford, Reading Bowie, Altoona). In an abbreviated two game 2018 SQUIRRELS AT A GLANCE series, the Squirrels lost game one against Bowie, were rained out in game two, and lost game three. Richmond did not win four series’ in a row all 2017. Richmond enters the series against the Yard Goats with a 0.5 game lead for first place in the Regular Season Record ..........................12-7 vs. Western Division .................................5-4 Western Division. -

National League News in Short Metre No Longer a Joke

RAP ran PHILADELPHIA, JANUARY 11, 1913 CHARLES L. HERZOG Third Baseman of the New York National League Club SPORTING LIFE JANUARY n, 1913 Ibe Official Directory of National Agreement Leagues GIVING FOR READY KEFEBENCE ALL LEAGUES. CLUBS, AND MANAGERS, UNDER THE NATIONAL AGREEMENT, WITH CLASSIFICATION i WESTERN LEAGUE. PACIFIC COAST LEAGUE. UNION ASSOCIATION. NATIONAL ASSOCIATION (CLASS A.) (CLASS A A.) (CLASS D.) OF PROFESSIONAL BASE BALL . President ALLAN T. BAUM, Season ended September 8, 1912. CREATED BY THE NATIONAL President NORRIS O©NEILL, 370 Valencia St., San Francisco, Cal. (Salary limit, $1200.) AGREEMENT FOR THE GOVERN LEAGUES. Shields Ave. and 35th St., Chicago, 1913 season April 1-October 26. rj.REAT FALLS CLUB, G. F., Mont. MENT OR PROFESSIONAL BASE Ills. CLUB MEMBERS SAN FRANCIS ^-* Dan Tracy, President. President MICHAEL H. SEXTON, Season ended September 29, 1912. CO, Cal., Frank M. Ish, President; Geo. M. Reed, Manager. BALL. William Reidy, Manager. OAKLAND, ALT LAKE CLUB, S. L. City, Utah. Rock Island, Ills. (Salary limit, $3600.) Members: August Herrmann, of Frank W. Leavitt, President; Carl S D. G. Cooley, President. Secretary J. H. FARRELL, Box 214, "DENVER CLUB, Denver, Colo. Mitze, Manager. LOS ANGELES A. C. Weaver, Manager. Cincinnati; Ban B. Johnson, of Chi Auburn, N. Y. J-© James McGill, President. W. H. Berry, President; F. E. Dlllon, r>UTTE CLUB, Butte, Mont. cago; Thomas J. Lynch, of New York. Jack Hendricks, Manager.. Manager. PORTLAND, Ore., W. W. *-* Edward F. Murphy, President. T. JOSEPH CLUB, St. Joseph, Mo. McCredie, President; W. H. McCredie, Jesse Stovall, Manager. BOARD OF ARBITRATION: S John Holland, President. -

TODAY's HEADLINES AGAINST the OPPOSITION Home

ST. PAUL SAINTS (10-11) vs IOWA CUBS (CHC) (9-10) RHP GRIFFIN JAX (2-1, 4.29) vs RHP ALEC MILLS (MLR) (0-1, 27.00) Friday, May 28th, 2021 - 7:08 pm (CT) - Des Moines, IA - Principle Park Game #22 - Road Game #10 TV: MiLB.TV RADIO: KFAN+ 2021 At A Glance TODAY'S HEADLINES AGAINST THE OPPOSITION Home .....................................................5-7 That Was Yesterday - The Saints winning streak marched on to four SAINTS VS IOWA Road ......................................................5-4 games with a 4-2 come-from-behind win over Iowa last night. Jhoan vs. LHP .............................................1-0 Duran again lived up to the expectations, striking out eight in four .209 ------------- BA ------------ .246 innings. St. Paul trailed 2-1 entering the ninth inning, and used two vs. RHP ..........................................9-11 singles, two hit by pitches and an error to plate three runs, scoring them .221 -------- BA W/2O ----------.173 Current Streak ....................................W4 their first comeback win in the ninth this season. .297 ------ BA W/RISP ---------.255 Most Games > .500 ..........................0 44 --------------RUNS ------------- 42 - Today the Saints strive for five in a row and secure their Most Games < .500 ..........................5 Today’s Game 12 ---------------- HR ---------------- 2 first series win of the year. RHP Griffin Jax heads out to the hill looking 8 ------------- STEALS ------------- 7 Overall Series ..................................0-2-1 to build on a six-inning, eight-strikeout performance in his last start. The 4.44 ------------- ERA ----------- 4.27 Saints are 6-3 against Iowa this season. Home Series ...............................0-1-1 87 --------------- K's -------------- 91 Away Series ................................0-1-0 Starters Strength - In the last full run through the Saints starting Extra Innings ........................................0-2 pitching rotation (May 21st), the St. -

Baseball in Japan and the US History, Culture, and Future Prospects by Daniel A

Sports, Culture, and Asia Baseball in Japan and the US History, Culture, and Future Prospects By Daniel A. Métraux A 1927 photo of Kenichi Zenimura, the father of Japanese-American baseball, standing between Lou Gehrig and Babe Ruth. Source: Japanese BallPlayers.com at http://tinyurl.com/zzydv3v. he essay that follows, with a primary focus on professional baseball, is intended as an in- troductory comparative overview of a game long played in the US and Japan. I hope it will provide readers with some context to learn more about a complex, evolving, and, most of all, Tfascinating topic, especially for lovers of baseball on both sides of the Pacific. Baseball, although seriously challenged by the popularity of other sports, has traditionally been considered America’s pastime and was for a long time the nation’s most popular sport. The game is an original American sport, but has sunk deep roots into other regions, including Latin America and East Asia. Baseball was introduced to Japan in the late nineteenth century and became the national sport there during the early post-World War II period. The game as it is played and organized in both countries, however, is considerably different. The basic rules are mostly the same, but cultural differences between Americans and Japanese are clearly reflected in how both nations approach their versions of baseball. Although players from both countries have flourished in both American and Japanese leagues, at times the cultural differences are substantial, and some attempts to bridge the gaps have ended in failure. Still, while doubtful the Japanese version has changed the American game, there is some evidence that the American version has exerted some changes in the Japanese game. -

Volume 10 Issue 2 April 22, 2019

Volume 10 Issue 2 April 22, 2019 VOLUME 10 | ISSUE 2 | 2019 THE OFFICIAL GAME PROGRAM OF THE SACRAMENTO RIVER CATS 4 2019 Schedule 7 Excerpt from Sacramento Baseball 9 Prospect Report: Heliot Ramos 11 River Cats Roster 23 River Cats Field Staff 26 Game Day Information 29 River Cats Foundation 30 San Francisco Giants Affiliates 31 Map of the Pacific Coast League 32 Top MLB/PCL Prospects 34 Scorecard 40 Raley Field Storefronts Menu 44 Raley Field Food Cart Map 49 Visiting Team 50 One-on-One with Shaun Anderson 56 Social Media Highlights 61 A-Z Guide CEO, MAJORITY OWNER DESIGN Susan Savage Aaron Davis & Mike Villarreal PRESIDENT PHOTOGRAPHERS Jeff Savage Kaylee Creevan & Ralph Thompson GENERAL MANAGER Chip Maxson CORPORATE PARTNERSHIPS Greg Coletti, Ellese Iliff, DIRECTOR, MARKETING Emily Williams Krystal Jones, & Ryan Maddox CONTRIBUTORS PRINTING Daniel Emmons, Conner Penfold Commerce Printing & Bill McPoil APRIL MAY SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT 1 2 3 4 TAC 5 TAC 6 TAC 1 abq 2 abq 3 rno 4 rno 7:05 7:05 7:05 5:35 10:05 7:05 7:05 7 TAC 8 TAC 9 lv 10 lv 11 lv 12 sl 13 sl 5 rno 6 rno 7 fre 8 fre 9 fre 10 fre 11 elp 1:05 12:05 7:05 7:05 7:05 5:35 5:35 1:05 6:35 6:35 12:05 7:05 7:05 7:05 14 sl 15 sl 16 lv 17 lv 18 lv 19 sl 20 sl 12 elp 13 elp 14 elp 15 16 fre 17 fre 18 fre 12:05 11:05 6:35 6:35 7:05 7:05 7:05 1:05 6:35 12:05 7:05 7:05 7:05 21 sl 22 sl 23 24 tac 25 tac 26 tac 27 tac 19 fre 20 fre 21 sl 22 sl 23 sl 24 sl 25 abq 1:05 12:05 6:00 7:00 7:00 5:00 1:05 6:35 6:35 12:05 7:05 7:05 5:35 28 tac 29 abq 30 abq 26 abq -

Base Ball and Trap Shooting

DEVOTED TO BASE BALL AND TRAP SHOOTING VOL. 63. NO. 5 PHILADELPHIA, APRIL A, 1914 PRICE 5 CENTS BALL! The Killifer Injunction Case and the Camnitz Damage Suit Not Permitted to Monopolize Entirely the Lime Light, Thanks to Many League, Club, and Individual Squabbles and Contentions from the training camp with an injured knee, according to word last night from Strife is still the order of the day Manager Birmingham, who ordered him in professional base ball, in keeping home. With shortstop Chapman©s leg icith the general unrest all over the broken and the pitching staff cut into civilized icorld. Supplementary to by the jumping of Falkenberg, the crip the Killifer and Camnitz law suits pling of Leibold means that the Naps we hear of friction in the Federal will start the season in a bad way. League over the Seaton case and the Schedule, and arc compelled to chronicle the season©s first row on Dreyfuss on War Path a ball field. Manager McGraw. of PITTSBURGH, Pa., April 1. Presi the Giants, being the victim of an dent Dreyfuss, of the Pittsburgh National irate Texas League player. The lat Club, "started for Hot Springs Monday est news of a day in the wide field of Base Ball is herewith giv night, taking with him the original con en: tracts of the Pittsburgh players for exhi bition to Judge Henderson in the Cam nitz damage suit at Hot Springs. On the way President Dreyfuss will be joined at Cincinnati by Lawyer Ellis G. Kinkead, © To Settle Seaton Dispute who has prepared a brief of several hun . -

Spalding's Official Base Ball Guide, 1910

Library of Congress Spalding's official base ball guide, 1910 SPALDING'S OFFICIAL BASE BALL GUIDE 1910 ,3I ^, Spalding's Athletic Library - FREDERICK R. TOOMBS A well known authority on skating, rowing. boxing, racquets, and other athletic sports; was sporting editor of American Press Asso- ciation, New York; dramatic editor; is a law- yer and has served several terms as a member of Assembly of the Legislature of the State of New York; has written several novels and historical works. R. L. WELCH A resident of Chicago; the popularity of indoor base ball is chiefly due to his efforts; a player himself of no mean ability; a first- class organizer; he has followed the game of indoor base ball from its inception. DR. HENRY S. ANDERSON Has been connected with Yale University for years and is a recognized authority on gymnastics; is admitted to be one of the lead- ing authorities in America on gymnastic sub- jects; is the author of many books on physical training. CHARLES M. DANIELS Just the man to write an authoritative book on swimming; the fastest swimmer the world has ever known; member New York Athletic Club swimming team and an Olym- pic champion at Athens in 1906 and London, 1908. In his book on Swimming, Champion Daniels describes just the methods one must use to become an expert swimmer. GUSTAVE BOJUS Mr. Bojus is most thoroughly qualified to write intelligently on all subjects pertaining to gymnastics and athletics; in his day one of America's most famous amateur athletes; has competed Spalding's official base ball guide, 1910 http://www.loc.gov/resource/spalding.00155 Library of Congress successfully in gymnastics and many other sports for the New York Turn Verein; for twenty years he has been prom- inent in teaching gymnastics and athletics; was responsible for the famous gymnastic championship teams of Columbia University; now with the Jersey City high schools. -

Spring / Summer 2020 Contents Support the Press

Spring / Summer 2020 Contents Support the Press General Interest 1 Help the University of Nebraska Press continue its New in Paperback/Trade 46 vibrant program of publishing scholarly and regional Scholarly Books 64 books by becoming a Friend of the Press. Distribution 95 To join, visit nebraskapress.unl.edu or contact New in Paperback/Scholarly 96 Erika Kuebler Rippeteau, grants and development Selected Backlist 100 specialist, at 402-472-1660 or [email protected]. Journals 102 To find out how you can help support a particular Index 103 book or series, contact Donna Shear, Press director, at Ordering Information 104 402-472-2861 or [email protected]. Ebooks available for each title unless otherwise indicated. Subject Guide Africa 14, 30–32, 66, 78 History/American 2, 9, 13, 17–18, 20, Native American & Indigenous Studies 34–38, 48–50, 55–58, 63, 65, 68, 70, 15, 39, 52–55, 71, 80, 82–84, 86–87, African American Studies 14, 16, 50, 80–81, 84–87, 96–99 95–98 78, 99 History/American West 11–12, 25, 38, Natural History 37, 54 American Studies 73–75 54, 57, 59, 73, 95 Philosophy 40, 88 Anthropology 79, 83, 85–87 History/World 7, 18, 61, 68–70, 88, Poetry 14, 29–33, 41, 54, 56 Art & Photograph 7, 83 92–94 Political Science 4, 8, 11, 13, 24, 66, 85, Jewish History & Culture 35, 40–44 Asia 6–7, 17, 47 99 Bible Studies 43–44 Journalism 8, 20, 57, 65 Religion 39–41, 43–44, 88, 94 Biography 1, 8–9, 18, 23, 25, 36, 47, 56, Law/Legal Studies 4, 57, 70 Spain 90, 92–94 59, 62 Literature & Criticism 10, 32, 41, 44, Sports 1–3, 16–19, 34–35, 46–51, 65 -

Baseball and Beesuboru

AMERICAN BASEBALL IMPERIALISM, CLASHING NATIONAL CULTURES, AND THE FUTURE OF SAMURAI BESUBORU PETER C. BJARKMAN El béisbol is the Monroe Doctrine turned into a lineup card, a remembrance of past invasions. – John Krich from El Béisbol: Travels Through the Pan-American Pastime (1989) When baseball (the spectacle) is seen restrictively as American baseball, and then when American baseball is seen narrowly as Major League Baseball (MLB), two disparate views will tend to appear. In one case, fans happily accept league expansion, soaring attendance figures, even exciting home run races as evidence that all is well in this best of all possible baseball worlds. In the other case, the same evidence can be seen as mirroring the desperate last flailing of a dying institution – or at least one on the edge of losing any recognizable character as the great American national pastime. Big league baseball’s modern-era television spectacle – featuring overpaid celebrity athletes, rock-concert stadium atmosphere, and the recent plague of steroid abuse – has labored at attracting a new free-spending generation of fans enticed more by notoriety than aesthetics, and consequently it has also succeeded in driving out older generations of devotees once attracted by the sport’s unique pastoral simplicities. Anyone assessing the business health and pop-culture status of the North American version of professional baseball must pay careful attention to the fact that better than forty percent of today’s big league rosters are now filled with athletes who claim their birthright as well as their baseball training or heritage outside of the United States. -

From Ppēsŭppol to Yagu: the Evolution of Baseball and Its Terminology in Korea

FROM PPĒSŬPPOL TO YAGU: THE EVOLUTION OF BASEBALL AND ITS TERMINOLOGY IN KOREA by Natasha Rivera B.A., The University of Minnesota, 2010 M.A., SOAS, University of London, 2011 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in The Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies (Asian Studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) August 2015 © Natasha Rivera, 2015 Abstract Baseball has shaped not only the English language, but also American society. From the early development of professional sport, to spearheading integration with Jackie Robinson’s first appearance, to even deploying “baseball ambassadors” in Japan as wartime spies, baseball has been at the forefront of societal change even as its popularity declined in the United States. Nonetheless, the sport’s global presence remains strong, presenting us with an opportunity to examine how baseball has shaped language and society outside North America. Baseball has an extensive set of specialized terms. Whether these words are homonyms of other English terms, or idioms unique to the sport, each term is vital to the play of the game and must be accounted for when introducing baseball to a new country. There are various ways to contend with this problem: importing the terms wholesale as loanwords, or coining neologisms that correspond to each term. Contemporary Korean baseball terminology is the still-evolving product of a historically contingent competition between two sets of vocabulary: the English and the Japanese. Having been first introduced by American missionaries and the YMCA, baseball was effectively “brought up” by the already baseball-loving Japanese who occupied Korea as colonizers shortly after baseball’s first appearance there in 1905. -

2019 California League Record Book & Media Guide

2019_CALeague Record Book Cover copy.pdf 2/26/2019 3:21:27 PM C M Y CM MY CY CMY K 2019 California League Record Book & Media Guide California League Championship Rings Displayed on the Front Cover: Inland Empire 66ers (2013) Lake Elsinore Storm (2011) Lancaster JetHawks (2014) Modesto Nuts (2017) Rancho Cucamonga Quakes (2015) San Jose Giants (2010) Stockton Ports (2008) Visalia Oaks (1978) Record Book compiled and edited by Chris R. Lampe Cover by Leyton Lampe Printed by Pacific Printing (San Jose, California) This book has been produced to share the history and the tradition of the California League with the media, the fans and the teams. While the records belong to the California League and its teams, it is the hope of the league that the publication of this book will enrich the love of the game of baseball for fans everywhere. Bibliography: Baarns, Donny. Goshen & Giddings - 65 Years of Visalia Professional Baseball. Top of the Third Inc., 2011. Baseball America Almanac, 1984-2019, Durham: Baseball America, Inc. Baseball America Directory, 1983-2018, Durham: Baseball America, Inc. Official Baseball Guide, 1942-2006, St. Louis: The Sporting News. The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, 2007. Baseball America, Inc. Total Baseball, 7th Edition, 2001. Total Sports. Weiss, William J. ed., California League Record Book, 2004. Who's Who in Baseball, 1942-2016, Who's Who in Baseball Magazine, Co., Inc. For More Information on the California League: For information on California League records and questions please contact Chris R. Lampe, California League Historian. He can be reached by E-Mail at: [email protected] or on his cell phone at (408) 568-4441 For additional information on the California League, contact Michael Rinehart, Jr.