CONFESSIONS of an APOSTATE This Is a Volume in the Arno Press Collection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

First Sunday of Advent November 29, 2020

First Sunday of Advent November 29, 2020 ADVENT EVENING OF REFLECTION Sunday, December 6 7 pm @ St. Francis- St. Maximilian Advent comes from the Lan word meaning "coming." Jesus is coming, and Advent is intended to be a season of preparaon for His arrival. While we typically regard Advent as a joyous sea- son, it is also intended to be a period of preparaon. Feast of the Immaculate Concepon of Mary Tuesday, December 8 Holy Day of Obligaon Masses at St. FrancisRSt. Maximilian 9:00 am and 7:00 pm (Bilingual) Mass at St. Mary Myscal Rose 7:00 pm La Inmaculada Concepción Martes 8 de diciembre Our food pantry is need of a working upright freezer. If you have one that you are no longer using and would like to donate please call the office 586.598.3314. Advent Wreaths & Candles Stewardship Thought WHY DO WE DO THAT? R CATHOLIC LIFE EXPLAINED Advent wreaths for families to place in In our First Reading today, the prophet their homes are available in the gather- Ezekiel uses the imagery of a shepherd Queson: When we say the Penitenal ing space. They are on the glass cabinet rescuing his sheep to illustrate how our Act at Mass, why do we strike our across from the bathrooms. A complete Lord God reaches out to those in need. chest three mes? set of a wreath and box of candles is In St. Mahew’s Gospel, Jesus clearly $15. A box of candles is $5. teaches that His followers must serve Answer: others with acts of Chrisan mercy and Our rituals and liturgical celebraons Advent means “coming”, we prepare love to enter the Kingdom of God. -

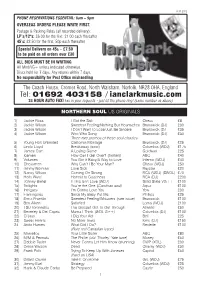

Clarky List 50 31/07/2012 13:06 Page 1

Clarky List 51_Clarky List 50 31/07/2012 13:06 Page 1 JULY 2012 PHONE RESERVATIONS ESSENTIAL : 8am – 9pm OVERSEAS ORDERS PLEASE WRITE FIRST. Postage & Packing Rates (all recorded delivery): LP’s/12"s: £6.00 for the first, £1.00 each thereafter 45’s: £2.50 for the first, 50p each thereafter Special Delivery on 45s – £7.50 to be paid on all orders over £30 ALL BIDS MUST BE IN WRITING All Mint/VG+ unless indicated otherwise. Discs held for 7 days. Any returns within 7 days. No responsibility for Post Office mis han dling The Coach House, Cromer Road, North Walsham, Norfolk, NR28 0HA, England Tel: 01692 403158 / ianclarkmusic.com 24 HOUR AUTO FAX! Fax in your requests - just let the phone ring! (same number as above) NORTHERN SOUL US ORIGINALS 1) Jackie Ross I Got the Skill Chess £8 2) Jackie Wilson Sweetest Feeling/Nothing But Heartaches Brunswick (DJ) £30 3) Jackie Wilson I Don’t Want to Lose/Just Be Sincere Brunswick (DJ £35 4) Jackie Wilson Who Who Song Brunswick (DJ) £30 Three rare promos of these soul classics 5) Young Holt Unlimited California Montage Brunswick (DJ) £25 6) Linda Lloyd Breakaway (swol) Columbia (WDJ) £175 7) James Carr A Losing Game Goldwax £25 8) Icemen How Can I Get Over? (brilliant) ABC £40 9) Volumes You Got it Baby/A Way to Love Inferno (WDJ) £40 10) Chessmen Why Can’t I Be Your Man? Chess (WDJ) £50 11) Jimmy Norman Love Sick Raystar £20 12) Nancy Wilcox Coming On Strong RCA (WDJ) (SWOL) £70 13) Herb Ward Honest to Goodness RCA (DJ) £200 14) Johnny Bartel If This Isn’t Love (WDJ) Solid State VG++ £100 15) Twilights -

Why Am I Doing This?

LISTEN TO ME, BABY BOB DYLAN 2008 by Olof Björner A SUMMARY OF RECORDING & CONCERT ACTIVITIES, NEW RELEASES, RECORDINGS & BOOKS. © 2011 by Olof Björner All Rights Reserved. This text may be reproduced, re-transmitted, redistributed and otherwise propagated at will, provided that this notice remains intact and in place. Listen To Me, Baby — Bob Dylan 2008 page 2 of 133 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................................................. 4 2 2008 AT A GLANCE ............................................................................................................................................................. 4 3 THE 2008 CALENDAR ......................................................................................................................................................... 5 4 NEW RELEASES AND RECORDINGS ............................................................................................................................. 7 4.1 BOB DYLAN TRANSMISSIONS ............................................................................................................................................... 7 4.2 BOB DYLAN RE-TRANSMISSIONS ......................................................................................................................................... 7 4.3 BOB DYLAN LIVE TRANSMISSIONS ..................................................................................................................................... -

Confirmation

CONFIRMATION December 1, 2020 Dear Parents and Students, You have elected to register your son/daughter for the St. Agnes Christian Formation program this year. When registering your son/daughter it is stated that our Confirmation program is a two-year program. This program challenges him or her to grow in his or her understanding of the Catholic faith and his or her personal relationship with God. There are several points to make you aware of in preparation for Confirmation (which starts in 8th grade with the student receiving the Sacrament with the completion of 9th grade studies) (due to pandemic this school year completion of 10th grade)). Successful completion of the curriculum includes once a month catechesis, service to others, and spending time with God in prayer. The greatest form of prayer is the celebration of the Mass. As Catholics, we are encouraged to attend weekly Mass in order to recognize God’s love more fully in the Word and Sacrament of the Holy Eucharist. While the pandemic poses a particular challenge at this time, students and their families are highly encouraged to either attend weekly Mass in person (Precautions are in place to ensure everyone’s safety) or to seek out an online Mass to encourage growth in love for Christ in preparation for Confirmation. Below is a list of other expectations. Remember, these “assignments” are designed to support our students in their desire to know, love, and serve our wonderful God while helping to prepare them for the reception of the Sacrament. This process for being Confirmed in the Spirit is a commitment from the parish, support from parents, and a commitment from the student that wishes to be Confirmed. -

The Women of the Confederacy, in Which Is Presented the Heroism Of

THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS ^' '^ Una vv Return this book on or before the Latest Date stamped below. A charge is made on all overdue books. U. of I. Library 14 M '3? JO/VS^ ioUTH R£S£HV£ m^ 16 1944 lA 13k FtB2^1975 /, InSS -5 1353 JflN i K' (1)815 MSR 1.2 i3S ftUG 3 1 1989 , nri!) ^jiij MAY 17 m sse ^c^ 130 DEC 6 l:iCb ocr I1148-S y,^ •^ '-^^^^ ^^ ^^ ' w ^ ^ Gerard C. Berthold University of Illinois Library at Urbana-Champaign ^4A^yo "o^. ^k^c^^/a^r^^--"^^'^'^ THE WOMEN OF THE CONFEDERACY In which is presented the heroism of the women of the Con- federacy with accounts of their trials during the War and the period of Reconstruction, with their ultimate triumph over adversity. Their motives and their achievements as told by writers and orators now preserved in permanent form. BY REV. J. L. UNDERWOOD Master of Aris, Mercer University, Captain and Chaplain in the Confederate Army New York and Washington THE NEALE PUBLISHING COMPANY 1906 Copyright, 1906 By J. L. UNDERWOOD DEDICATION To the memory of Mrs. EivIzabeith Thomas Curry, whose remains rest under the live oaks at Bainbridge, Ga., who cheerfully gave every available member of her family to the Confederate Cause, and with her own hands made their gray jackets, and who gave to the author her Christian patriot daughter, who has been the companion, the joy and the crown of his long and happy life, this volume is most affectionately dedicated. If . CONTENTS Chapter Page I. Symposium of Tributes to Coneederatd Women, 19 Tribute of President Jefferson Davis, 20 Tribute of a Wounded Soldier, 21 Tribute of a Federal Private Soldier, 21 Joseph E. -

St. Martins Knights of Columbus Council #7194 CURRENT OFFICERS

St. Martins Knights of Columbus Council #7194 News of the Knights June 2019 www.stmartinskofc.org 537 Route T, Jefferson City, MO 65109 (573) 584-3200 Our next meetings will be Thursday, June 13, 2019. The Rosary will begin at 6:45 p.m. and the Council Meeting at 7:00 p.m. The Home Association will begin immediately after the Council Meeting, if needed. CURRENT OFFICERS Chaplain - Fr. Stephen Jones Financial Secretary – Steve Scheulen Grand Knight – Andy Distler Treasurer – Bob Angerer Deputy Grand Knight – Mac Gaono Recorder – Chancellor – Don Carel Advocate – Brian Francka Inside Guard – Terry Boeckman Warden – Jason Cooper Outside Guard – Kevin Boeckman District Deputy- Jeff Brondel Cell # 573-893-5045 Trustee 3rd yr – Richard Clarkston Home Association President – Joe Lueckenotte Trustee 2nd yr – Ambrose Buechter Insurance Agent – Dustin Dolce Cell # 573-230-6902 Trustee 1st year – Dave Amos E-mail – [email protected] Lecturer– Bruce Brondel Ordination Brad Berhorst ordination as Priest will be held June 29, 2019 at the Cathedral of St Joseph. He will perform his first mass on Sunday June 30 @ 3:00 at St. Martins. The Knights will be hosting a dinner after the mass at the Hall. Help will be needed that day. A sign-up sheet will be posted in the Kitchen. Safe Kids Training All officers and anybody that will be working with kids needs to be trained for the Safe Kids program. The training can be done on the Knights of Columbus web site. There is two different modules. One module is for the officers and the other module is for anybody else. -

Bulletin Irlandejun06porpdf

The Priestly Society of Saint Pius X in Ireland Saint Pius X House 12 Tivoli Terrace South Dún Laoghaire, County Dublin The Society of Saint Pius X Telephone: (01) 284 2206 Very Rev. Ramón Anglés, Superior Rev. Régis Babinet Bulletin for Ireland Saint John’s Presbytery Corpus Christi Priory 1 Upper Mounttown Road Connaught Gardens Dún Laoghaire, Co. Dublin Athlone, Co. Roscommon Telephone: (01) 280 9407 Telephone: (090) 649 2439 Resident Priest: Resident Priests: Rev. Paul Biérer Rev. Craig Bufé Rev. Adam Portugal CONTACT Saint Pius V Chapel 78 Andersonstown Road Dún Laoghaire or Belfast, Co. Antrim Mr. McKeown (048) 9445 3654 Our Lady of the Rosary Church Shanakiel Road Athlone or Sunday’s Well, Co. Cork Mr. O’Connor (021) 437 1196 Our Lady of Knock and St Patrick Chapel Unit 5 Richbrook Business Park, Dún Laoghaire or Mill Rd, Newry, Co. Down Mr. McArdle (048) 3082 5730 Our Lady of Fatima Chapel Athlone or Kesh, Co. Fermanagh Dr. Bastian (048) 6863 1169 Saint Joseph’s Mass Centre Athlone or Tralee, Co. Kerry Mrs. Dennehy (068) 43123 Cashel Mass Center Athlone or Co. Tipperary Mr. Walsh (062) 61028 June 2006 Galway Mass Centre Athlone Chapel of new Clinic by N6 Co. Galway Website : www.ireland.sspx.net Devotions & Activities at St John’s Congregation of "mixed life", that is, a blend of the active and contemplative lives. Rosary daily at 6 pm While the Sisters are not a totally active Order like teaching Orders, neither are they totally cloistered like the Carmelites. Our Lord Himself lived a mixed life, Every Sunday: Exposition and Benediction of the Blessed Sacrament at 10.30 am preaching and working miracles, then retiring to places of solitude where He could Every Thursday: Benediction of the Blessed Sacrament and Miraculous Medal spend many hours in prayer. -

On John Lennon's Music

“She Said She Said” – The Influence of "Feminine Voices" on John Lennon’s Music (1) John Lennon’s songs show the recurrent influence of female voices, and this can be shown by musicological comparisons of Lennon compositions with earlier songs sung by women, which he was familiar with. Some of these resemblances have already been pointed out; others are discussed here for the first time. Although these influences featured throughout Lennon’s work, we will focus on the early Beatles (1958-1963), and how specific songs, mostly US R&B, influenced Lennon’s songwriting (he wrote in partnership with Paul McCartney, but it is possible to establish the balance of their contributions by reference to secondary literature, eg Miles 1997, Sheff and Golson 1982, MacDonald 2005). (2) In the period 1958-1963 the Beatles developed from a covers band into the most famous popular music group in the world. The group were constantly listening for new material (they had a huge repertoire of covers), and were absorbing and experimenting with different musical styles in response to increasingly feminised audiences. They initially saw their songwriting as addressing a primarily female audience (Lewisohn 2013). Moreover, almost all the works featuring woman’s voices identified in Lennon’s work come from this period. (3) Lennon, by most accounts, was the “macho” Beatle and was occasionally violent towards women, so it seems surprising that he led the way in covering and borrowing from songs sung by women, most particularly, early 60s US girl-groups such as The Shirelles, the Marvelettes and The Cookies. (4) Most accounts of the Beatles' influences emphasise male artists such as Elvis Presley, Little Richard, Buddy Holly and Chuck Berry (Dafydd, Crampton 1996, 4; Gould 2007, 58–68). -

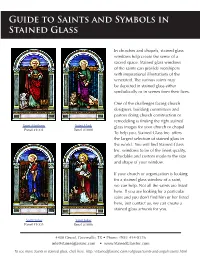

Guide to Saints and Symbols in Stained Glass

Guide to Saints and Symbols in Stained Glass In churches and chapels, stained glass windows help create the sense of a sacred space. Stained glass windows of the saints can provide worshipers with inspirational illustrations of the venerated. The various saints may be depicted in stained glass either symbolically or in scenes from their lives. One of the challenges facing church designers, building committees and pastors doing church construction or remodeling is finding the right stained Saint Matthew Saint Mark glass images for your church or chapel. Panel #1001 Panel #1000 To help you, Stained Glass Inc. offers the largest selection of stained glass in the world. You will find Stained Glass Inc. windows to be of the finest quality, affordable and custom made to the size and shape of your window. If your church or organization is looking for a stained glass window of a saint, we can help. Not all the saints are listed here. If you are looking for a particular saint and you don’t find him or her listed here, just contact us, we can create a stained glass artwork for you. Saint Luke Saint John Panel #1005 Panel #1006 4400 Oneal, Greenville, TX • Phone: (903) 454-8376 [email protected] • www.StainedGlassInc.com To see more Saints in stained glass, click here: http://stainedglassinc.com/religious/saints-and-angels/saints.html The following is a list of the saints and their symbols in stained glass: Saint Symbol in Stained Glass and Art About the Saint St. Acathius may be illustrated in Bishop of Melitene in the third century. -

Faces-Around-The-Cross.Pdf

This Lenten devotional guide comes from Keep Believing Ministries. You can find us on the Internet at www.KeepBelieving.com. Questions or Comments? We love getting your feedback. Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/KeepBelievingMinistries Twitter: https://twitter.com/raypritchard Email: [email protected] 2 Were You There? That’s the question asked by a beloved spiritual: “Were you there when they crucified my Lord?” No, we weren’t there, but we have the next best thing. We have the stories of those who were there when Jesus entered Jerusalem for the final time. We know who they were, what they said, what they did, and in many cases, we know why they did it. In this Lenten series we will meet the men and women who were the “faces around the cross.” Our journey begins with a blind man who found the miracle he needed, and it ends with a man who could see but couldn’t recognize Jesus on the road to Emmaus. In between, we’ll meet a woman who poured perfume on Jesus’ feet and then wiped his feet with her hair. Herod thought Jesus was a joke, while Pilate’s wife couldn’t keep him out of her dreams. We’ll meet a thief who didn’t believe and one who did. We’ll spend several days thinking together about Judas. We know what he did, but after two thousand years, we still wonder why he did it. Many other men and women will cross our path as we walk with Christ on the road to the cross and the empty tomb: Caiaphas who came so close to the truth. -

Celtic Spirituality Study Tour

Course Syllabus SPRING SUMMER 2017 CELTIC CHRISTIANITY STUDY TOUR HIST / SPIR 0639 MAY 29 – JUNE 9, 2017 INSTRUCTOR: DR. DAVID SHERBINO Email: [email protected] Tel: 416 226 6620 x 6741 To access your course material, please go to http://classes.tyndale.ca. Course emails will be sent to your @MyTyndale.ca e-mail account. For information how to access and forward emails to your personal account, see http://www.tyndale.ca/it/live-at-edu. I. COURSE DESCRIPTION This course is an introduction to Celtic Spirituality. It will focus upon the work of St. Patrick and St. Columba, two noted individuals in the Celtic tradition. The course will explore various themes such as creation, redemption and the Trinity as expressed through a people with a holistic view of the world. The course will include an eleven-day trip to Ireland where will trace the footsteps of St. Patrick and then to Scotland to visit Iona and the community started by St. Columba and then to Holy Island Lindisfarne. In addition to the trip there will be lectures, two personal pilgrimages, as well as daily worship in the Celtic tradition. II. LEARNING OUTCOMES At the end of the course, students should be able to: have a better appreciation and understanding of the Celtic tradition. The lessons learned and the principles incorporated into the student's spiritual discipline and worldview will have a beneficial effect with respect to their personal spiritual formation. III. COURSE REQUIREMENTS A. REQUIRED READING: Bradley, Ian. Colonies of Heaven. London: Darton Longman and Todd Ltd, 2000. De Waal, Esther. -

Rubber Souls: Rock and Roll and the Racial Imagination

Rubber Souls: Rock and Roll and the Racial Imagination The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Hamilton, John C. 2013. Rubber Souls: Rock and Roll and the Racial Imagination. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:11125122 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Rubber Souls: Rock and Roll and the Racial Imagination A dissertation presented by Jack Hamilton to The Committee on Higher Degrees in American Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of American Studies Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts April 2013 © 2013 Jack Hamilton All rights reserved. Professor Werner Sollors Jack Hamilton Professor Carol J. Oja Rubber Souls: Rock and Roll and the Racial Imagination Abstract This dissertation explores the interplay of popular music and racial thought in the 1960s, and asks how, when, and why rock and roll music “became white.” By Jimi Hendrix’s death in 1970 the idea of a black man playing electric lead guitar was considered literally remarkable in ways it had not been for Chuck Berry only ten years earlier: employing an interdisciplinary combination of archival research, musical analysis, and critical race theory, this project explains how this happened, and in doing so tells two stories simultaneously.