EXPLORING ACCESS to CATHOLIC DIOCESAN ARCHIVES in CANADA by Tyyne Rae Petrowski

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The History of The

The History of the Œcumenical Canonical Orthodox Church Worldwide The Holy Eastern Orthodox Catholic and Apostolic Church in North America The American Orthodox Catholic Church Old Catholic Orthodox Church Archbishop Gregory Morra, OSB Archbishop Scholarios-Gennadius III, OSB Metropolitan Œcumenical Canonical Orthodox Church Worldwide Episcopal Imprimatur of the Holy Synod of the Œcumenical Canonical Orthodox Church Worldwide Old Catholic Orthodox Church This history of the church is hereby released under the authority of the Holy Synod of the Œcumenical Canonical Orthodox Church Worldwide which is a direct blood descendant of the American Orthodox Catholic Church chartered in 1927 by Metropolitan Platon and later led by Archbishop Aftimios Ofiesh of Brooklyn, New York and eventually recognized as The Holy Eastern Orthodox Catholic and Apostolic Church in North America. In its current form the Holy Synod of the Œcumenical Canonical Orthodox Church Worldwide and the Old Catholic Orthodox Church subsidiary recognizes the contributions of the early fathers of this historic church in the person of Metropolitan-Patriarch Denis M. Garrison (Emeritus) through the lineage of Archbishop Aftimios of blessed memory as the true spiritual father of the Church. Therefore, the Holy Synod hereby confers its official imprimatur on the history of the Œcumenical Canonical Orthodox Church Worldwide as a direct historical descendant of the American Orthodox Catholic Church as outlined in this document. Archbishop Scholarios-Gennadius III, OSB Metropolitan -

Valentine Schaaf, O.F.M

t This number of THE AMERICAS is respectfully dedicated to THE MOST REVEREND VALENTINE SCHAAF, O.F.M. MINISTER GENERAL of the ORDER OF FRIARS MINOR MOST REVEREND VALENTINE SCHAAF, O.F.M. MINISTER GENERAL of the FRANCISCAN ORDER 113th Successor Of Saint Francis The Academy of American Franciscan History and the editorial staff of THE AMEEICAS join with the many other Franciscan institutions and publications in rendering a filial homage of respect and devotion to the Most Reverend Valentine Schaaf, who was recently appointed Minister Gen eral Of the Order of Friars Minor by His Holiness, Pope Pius XII. Father Valentine well merits the singular honor of being the first American friar to hold the highest office in the Franciscan Order since its foundation seven centuries ago: Father Valentine was born in Cincinnati, Ohio, March' 18, 1883. He entered the Franciscan Order August 15, 1901. After completing his studies in the Franciscan seminaries at Cincinnati, Ohio, Louisville, Kentucky, and Oldenburg, Indiana, he was ordained to the priesthood June 29, 1909. He taught at Saint Francis College, Cincinnati from 1909 to 1918. He then pursued graduate studies in Canon Law at the Catholic University of America, Washington, D. C, where he received the following degrees: Bachelor of Sacred Theology and Bachelor of Canon Law in 1919; Licentiate of Canon Law, 1920; and Doctor of Canon Law, 1921. Father Schaaf served as Professor of Canon Law at the Franciscan Seminary, Oldenburg, Indiana, 1921-1923, in which year he accepted the Associate Professorship of Canon Law at the Catholic University of America (1923-1928), becoming full Professor in 1928. -

Pentecost Sunday Monday & Tuesday CLOSED May 23Rd, 2021 Wednesday & Thursday 9:00 A.M.A.M.---- 12:00 P.M

OUR LADY OF GOOD COUNSEL PARISH 114 MacDonald Avenue, Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario P6B 1H3 Phone: (705) 942-8546 Fax: (705) 942-8674 OFFICE HOURS : Pentecost Sunday Monday & Tuesday CLOSED May 23rd, 2021 Wednesday & Thursday 9:00 a.m.a.m.---- 12:00 p.m. & 1:00p.m.1:00p.m.---- 5:00 p.m. Friday CLOSED SUNDAY MASSES Sunday 10:00 a.m. Church Parking Lot WEEKDAY LITURGIES Tuesday to Friday 9:15 a.m. Church Parking Lot E-MAIL : [email protected] WEBSITE : olgoodcounselssm.com PARISH STAFF ECONCILIATION Pastor: Rev. Paul Conway RECONCILIATION Deacons: Rev. Mr. Walter Morrow (retired) (At this time by appointment only) Diocesan Order of Women: Raymonde Brant Secretary: Sue Solomon SACRAMENT OF INITIATION (Baptism) REGISTRATION FORMS are available PARISH PASTORAL COUNCIL for pick up in the foyer of the church. Dan Drazenovich Randy Johnson Vincent LaRue Finance Member MARRIAGE Outreach Member Liturgy Member Please contact the parish office. Christian Formation Member A MINIMUM OF SIX MONTHS NOTICE IS REQUIRED . ADORATION CHAPEL Closed until further notice ANOINTING OF THE SICK If you are sick and go to the hospital, PRAYER LINE REQUESTS please call the parish office 705-942-8546. This will allow us to arrange that you to place a prayer request, please phone: have the Sacrament of the Sick and a Pastoral Visit. Laverne……….... 942-7630 (answering machine) Also, Eucharist is brought once a week to those in the hospital by a Pastoral Team member. Betty……………...649-3611 (answering machine) “O N CALL ” P RIEST CHURCH ENVELOPES A priest is available in the city for emergencies 24/7. -

Against John Lane

Against John Lane R. J. M. I. By The Precious Blood of Jesus Christ, The Grace of the God of the Holy Catholic Church, The Mediation of the Blessed Virgin Mary, Our Lady of Good Counsel and Crusher of Heretics, The Protection of Saint Joseph, Patriarch of the Holy Family, The Intercession of Saint Michael the Archangel and the cooperation of Richard Joseph Michael Ibranyi To Jesus through Mary Judica me Deus, et discerne causam meaum de gente non sancta as homine iniquo et doloso erue me Ad Majorem Dei Gloriam Original version: 9/2001; Current version: 12/2009 Mary’s Little Remnant 302 East Joffre St. TorC, NM 87901-2878 Website: www.JohnTheBaptist.us (Send for a free catalog) 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS RJMI’ CONDEMNATION LETTER ............................................................................................................... 5 FALSE ECUMENISM ......................................................................................................................................... 5 IN COMMUNION WITH NON-CATHOLICS: DOES NOT PROFESS THE FAITH ................................................................... 7 CONCLUSION: TAKE SIDES ................................................................................................................................ 9 REFUTATION OF LANE’S ACCUSATIONS .................................................................................................. 10 NOTHING TRUE IN IBRANYI’S WRITINGS 9/28 ................................................................................................... -

Biography: Most Reverend William Francis Murphy, D.D., S.T.D

Biography: Most Reverend William Francis Murphy, D.D., S.T.D. Bishop-Emeritus, Diocese of Rockville Centre William Francis Murphy was born May 14, 1940 in West Roxbury, Massachusetts to Cornelius and Norma Murphy. He attended Boston Public Schools, including Boston Latin School for Harvard College, and pursued studies for the priesthood at St. John's (Major) Seminary in Boston and the Pontifical Gregorian University in Rome, where he earned a doctorate in Sacred Theology. He was ordained a priest of the Archdiocese of Boston at Saint Peter's Basilica, Vatican City, on December 16, 1964. Father Murphy returned to Boston after his ordination. Over the next ten years there he served as an assistant pastor in Groveland, Winchester and East Boston while also teaching at Emmanuel College and Pope John XXIII Seminary. In 1974, Father Murphy was called back to Rome where he became a member of the Pontifical Commission Jusititia et Pax. He was appointed Under Secretary in 1980, a position he would hold for seven years. He authored various publications for the commission, including Person, Nation and State in 1982 and True Dimensions of Development Today a year later. While in Rome, Father Murphy was also a lecturer in Theology at the Pontifical Gregorian University and the Pontifical University of Saint Thomas. Father Murphy returned to the Boston Archdiocese in 1987 to serve in several capacities, including Secretary of Community Relations, Director of the Office of Social Justice, Director of Pope John XXIII Seminary, and Administrator of Sacred Heart Parish, Lexington, Massachusetts. Father Murphy was named Chaplain of Honor to His Holiness in 1979, with the title of Monsignor and elevated to the rank of Prelate of Honor in 1987 by Pope John Paul II. -

1 Fr. Luke Dysinger, OSB the Story of the Benedictines of Szechwan

THE BENEDICTINE FOUNDATIONS IN XISHAN AND CHENGDU, 1929-1952 Fr. Luke Dysinger, OSB Mission and Monasticism, Studia Anselmiana 158, Analecta Monastica 13, (Sant’ Anselmo, Rome; EOS Verlag, Germany, 2013), pp. 185-195. The story of the Benedictines of Szechwan Province during the first half of the Twentieth Century can be divided into three epochs or phases encompassing two geographic locations. The three phases correspond to the first three superiors of the monastery, each of whom possessed a unique vision of how Benedictine monasticism could best serve the needs of the Catholic Church in China. The two geographic locations are: Xishan, near Shunqing, where the community was first established in 1929; and Chengdu, the capital of Szechwan Province where in 1942 the monks were compelled by the vicissitudes World War II to seek refuge 1: CONTEMPLATIVE ASPIRATIONS 1927-1933: Xihan, Prior Jehan Joliet In 1926 Dom Jehan Joliet, a monk of the Abbey of Solesmes, and Dom Pie de Cocqueau of the Abbey of St. André (now know as SintAndries, Zevenkerken), departed the port of Marseilles for Beijing. They were to establish a new monastic foundation that would be a canonical dependency of St. André.1 The Benedictine Abbey of St. André had been designated at its inception as a “Monastery for the Missions”. Since 1898 the community had been committed to monastic missionary work in Brazil by its founder, Abbot Gerard Van Caloen; and in 1910 his successor, Theodore Neve, pledged the community to work in Africa by accepting the Apostolic Prefecture of Katanga in the Congo. Through their publication of Les Bulletin des Missions the monks of St. -

The “Doctrine of Discovery” and Terra Nullius: a Catholic Response

1 The “Doctrine of Discovery” and Terra Nullius: A Catholic Response The following text considers and repudiates illegitimate concepts and principles used by Europeans to justify the seizure of land previously held by Indigenous Peoples and often identified by the terms Doctrine of Discovery and terra nullius. An appendix provides an historical overview of the development of these concepts vis-a-vis Catholic teaching and of their repudiation. The presuppositions behind these concepts also undergirded the deeply regrettable policy of the removal of Indigenous children from their families and cultures in order to place them in residential schools. The text includes commitments which are recommended as a better way of walking together with Indigenous Peoples. Preamble The Truth and Reconciliation process of recent years has helped us to recognize anew the historical abuses perpetrated against Indigenous peoples in our land. We have also listened to and been humbled by courageous testimonies detailing abuse, inhuman treatment, and cultural denigration committed through the residential school system. In this brief note, which is an expression of our determination to collaborate with First Nations, Inuit and Métis in moving forward, and also in part a response to the Calls to Action of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, we would like to reflect in particular on how land was often seized from its Indigenous inhabitants without their consent or any legal justification. The Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops (CCCB), the Canadian Catholic Aboriginal Council and other Catholic organizations have been reflecting on the concepts of the Doctrine of Discovery and terra nullius for some time (a more detailed historical analysis is included in the attached Appendix). -

Canon Law and Ecclesiology II the Ecclesiological Implications of the 1983 Code of Canon Law

302 THEOLOGICAL TRENDS Canon Law and Ecclesiology II The Ecclesiological Implications of the 1983 Code of Canon Law Introduction N A PREVIOUS article, published in The Way, January 1982, I gave an I outline of the highly centralized and clerical view of the Church that was common in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. This was the view of the Church that was expounded in most seminary text-books on the subject. It was this notion of the Church, too, that was reflected in the 1917 Code of Canon Law, and I indicated a number of examples of this centralized approach from the 1917 Code: local customs as such were considered undesirable (C.5); bishops were forbidden to grant dispensations from the general law of the Church, unless the faculty to do so had been expressly granted them by the Pope, or the case was particularly urgent. I also indicated that this same theological outlook was evident in the whole structure and content of Book II of the 1917 Code. I went on then to show how the second Vatican Council put forward a doctrine of the Church which puts greater emphasis on the importance of the local Church. The universal Church is now seen not primarily as a society of individuals, but as abody with different organs, each having its own proper characteristics, a communion of churches, together making up the Catholic Church. In this second article, I shall consider how this conciliar teaching has influenced the structure and contents of the new Code of Canon Law, promulgated by Pope John Paul II on 25 January of this year, 1983. -

Vancouver Priest Named Bishop Of

Dec. 16, 2013 Dear Editors and News Directors: A former Vancouver priest and head of the two Catholic colleges at UBC was ordained bishop of Canada's largest-area and northernmost diocese Sunday. Please see photo below. Most Reverend Mark Hagemoen is the new Bishop of the Diocese of Mackenzie-Fort Smith, based in Yellowknife. Principal consecrator was Archbishop Gerard Pettipas, CSSR, of the Diocese of Grouard-McLennan. Co-consecrators were Archbishop J. Michael Miller of Vancouver and Archbishop Richard Smith of Edmonton. One of the largest dioceses in the world, Mackenzie-Fort Smith includes most of the Northwest Territories and parts of Nunavut and Saskatchewan, covering 1.5 million square kilometres. It has a population of 49,150 and a Catholic population of about 27,000, almost equally divided between aboriginal and non-aboriginal. Mackenzie-Fort Smith is a mission diocese supported by the Pontifical Mission Societies, an agency under the jurisdiction of the Vatican Congregation for the Evangelization of Peoples. The diocese has been without a bishop since Bishop Murray Chatlain was appointed archbishop of the Archdiocese of Keewatin-Le Pas in Manitoba last year. -30- More information: Communications Director Paul Schratz [email protected] 604-505-9411 Backgrounder Msgr. Mark Hagemoen was born and raised in Vancouver and has served in parishes from Chilliwack to Vancouver for more than 20 years. He received his BA from UBC and his Master of Divinity at St. Peter's Seminary in London, Ont. He was ordained a priest in 1990. He also has a certificate in youth ministry studies, a diploma for advanced studies in ministry, and earned a doctorate in ministry from Trinity Western University in 2007. -

State of Indiana ) in the Marion Superior Court ) Ss: County of Marion ) Cause No

Filed: 5/11/2020 7:32 PM Clerk Marion County, Indiana STATE OF INDIANA ) IN THE MARION SUPERIOR COURT ) SS: COUNTY OF MARION ) CAUSE NO. 49D01-1907-PL-27728 JOSHUA PAYNE-ELLIOTT, ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) ROMAN CATHOLIC ARCHDIOCESE OF ) INDIANAPOLIS, INC., ) ) Defendant. ) ARCHDIOCESE’S MEMORANDUM OF LAW IN SUPPORT OF RECONSIDERATION OF MOTION TO DISMISS The Archdiocese respectfully submits this motion to offer clarification on the questions of canon law raised by the Court’s May 1 Order (“Order”)—namely, whether Cathedral could have appealed the Archdiocese’s directive, and whether the actions in this case proceeded from the highest ecclesiastical authority. Order 6-7. The Archdiocese recognizes that these questions were not fully explored in the parties’ briefing on the motion to dismiss and that, due to the coronavirus, the Court was unable to address these issues at oral argument. Accordingly, the Archdiocese respectfully asks the Court to reconsider the ruling with the benefit of additional clarity on the key canon-law matters it has identified. Taking the Complaint and exhibits as true, and taking judicial notice of undisputed canon law, the Archbishop’s directive to Cathedral could not be appealed within the Church, and the Archbishop is the “highest ecclesiastical authority”—as the Order uses that term—over Cathedral’s affiliation with the Catholic Church. Should the Court in considering this jurisdictional question under Rule 12(b)(1) wish to consider evidence on how canon law governs the relationships among Cathedral, the Archbishop, and the broader Church, the Archdiocese submits an affidavit from Fr. Joseph L. Newton, an expert in canon law, attached as Exhibit A. -

Products and Services Catalogue Digital Archive Services National Archives Service Organization

Products and Services Catalogue Digital archive services National Archives Service Organization Version 1.0 Date 11-1-2018 Status Final Disclaimer: this English version is a translation of the original in Dutch for information purposes only. In case of a discrepancy, the Dutch original will prevail. Final | PDC Digital archive services | 11-1-2018 Contents 1 PRODUCTS AND SERVICES CATALOGUE ................................................................................................................ 4 1.1 PURPOSE ..................................................................................................................................................................... 4 1.2 TARGET GROUP ............................................................................................................................................................ 4 1.3 POSITION OF THE PRODUCTS AND SERVICES CATALOGUE ................................................................................................. 4 1.4 STRUCTURE .................................................................................................................................................................. 5 2 OUTSOURCED RECORDS MANAGEMENT AND TRANSFERRED INFORMATION OBJECTS ................................... 6 2.1 OUTSOURCED RECORDS MANAGEMENT........................................................................................................................... 6 2.2 TRANSFERRED INFORMATION OBJECTS ........................................................................................................................... -

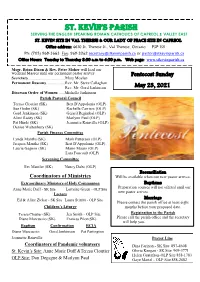

Pentecost Sunday, May 23, 2021

ST. Kevin’S PariSh SERVING THE ENGLISH SPEAKING ROMAN CATHOLICS OF CAPREOL & VALLEY EAST St. Kevin Site in Val Therese & Our Lady of Peace Site in Capreol Office address: 4610 St. Therese St., Val Therese, Ontario P3P 1S5 Ph: (705) 969-3663 Fax: 969-3262 [email protected] or [email protected] Office Hours: Tuesday to Thursday 8:30 a.m to 4:30 p.m. Web page: www.stkevinparish.ca Msgr. Brian Dixon & Rev. Peter Moher will lead our weekend Masses until our permanent pastor arrives Pentecost Sunday Secretary.................................................Mary Moylan Permanent Deacons...................Rev. Mr. Steve Callaghan Rev. Mr. Gord Jenkinson May 23, 2021 Diocesan Order of Women ......Michelle Jenkinson Parish Pastoral Council Teresa Cloutier (SK) Bert D'Appolonia (OLP) Sue Godin (SK) Rachelle Carriere (OLP) Gord Jenkinson (SK) Gerard Regimbal (OLP) Aline Radey (SK) Marlynn Paul (OLP) Pat Hinds (SK) Jeannette Rainville (OLP) Denise Waltenbury (SK) Parish Finance Committee Lynda Mantha (SK) Mark Patterson (OLP) Jacques Mantha (SK) Bert D'Appolonia (OLP) Laurie Gagnon (SK) Mario Mauro (OLP) Lara Foucault (OLP) Screening Committee Erv Mantler (SK) Nancy Dube (OLP) Reconciliation Coordinators of Ministries Will be available when our new pastor arrives. Extraordinary Ministers of Holy Communion Baptisms Preparation courses will not offered until our Anne Marie Duff - SK Site Lorraine Green - OLP Site new pastor arrives. Lectors Marriage Ed & Aline Zickar - SK Site Laura Stirritt - OLP Site Please contact the parish office at least eight Children’s Liturgy months before your proposed date. Teresa Cloutier (SK) Jen Smith - OLP Site Registration in the Parish Diane Marcuccio (SK) Frances Pilon(SK) Please call the parish office and the secretary will help you.