Cousins Across the Pond: Crises in Westminster and the Parliamentary Model's Usefulness for Reform of the U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Amendment) Bill

Holocaust (Return of Cultural Objects) (Amendment) Bill EXPLANATORY NOTES Explanatory notes to the Bill, prepared by the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport with the agreement of Theresa Villiers, are published separately as Bill 182—EN. Bill 182 57/1 Holocaust (Return of Cultural Objects) (Amendment) Bill CONTENTS 1 Holocaust (Return of Cultural Objects) Act 2009: repeal of sunset provision 2 Extent, commencement and short title Bill 182 57/1 Holocaust (Return of Cultural Objects) (Amendment) Bill 1 A BILL TO Prevent the Holocaust (Return of Cultural Objects) Act 2009 from expiring on 11 November 2019. E IT ENACTED by the Queen’s most Excellent Majesty, by and with the advice and consent of the Lords Spiritual and Temporal, and Commons, in this present BParliament assembled, and by the authority of the same, as follows:— 1 Holocaust (Return of Cultural Objects) Act 2009: repeal of sunset provision In section 4 of the Holocaust (Return of Cultural Objects) Act 2009— (a) in the heading, for “, commencement and sunset” substitute “and commencement”, and (b) omit subsection (7) (which provides for the Act to expire after 10 years). 5 2 Extent, commencement and short title (1) This Act extends to— (a) England and Wales, and (b) Scotland. (2) This Act comes into force on the day on which it is passed. 10 (3) This Act may be cited as the Holocaust (Return of Cultural Objects) (Amendment) Act 2018. Bill 182 57/1 Holocaust (Return of Cultural Objects) (Amendment) Bill A BILL To prevent the Holocaust (Return of Cultural Objects) Act 2009 from expiring on 11 November 2019. -

The Sovereignty of the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories in the Brexit Era

Island Studies Journal, 15(1), 2020, 151-168 The sovereignty of the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories in the Brexit era Maria Mut Bosque School of Law, Universitat Internacional de Catalunya, Spain MINECO DER 2017-86138, Ministry of Economic Affairs & Digital Transformation, Spain Institute of Commonwealth Studies, University of London, UK [email protected] (corresponding author) Abstract: This paper focuses on an analysis of the sovereignty of two territorial entities that have unique relations with the United Kingdom: the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories (BOTs). Each of these entities includes very different territories, with different legal statuses and varying forms of self-administration and constitutional linkages with the UK. However, they also share similarities and challenges that enable an analysis of these territories as a complete set. The incomplete sovereignty of the Crown Dependencies and BOTs has entailed that all these territories (except Gibraltar) have not been allowed to participate in the 2016 Brexit referendum or in the withdrawal negotiations with the EU. Moreover, it is reasonable to assume that Brexit is not an exceptional situation. In the future there will be more and more relevant international issues for these territories which will remain outside of their direct control, but will have a direct impact on them. Thus, if no adjustments are made to their statuses, these territories will have to keep trusting that the UK will be able to represent their interests at the same level as its own interests. Keywords: Brexit, British Overseas Territories (BOTs), constitutional status, Crown Dependencies, sovereignty https://doi.org/10.24043/isj.114 • Received June 2019, accepted March 2020 © 2020—Institute of Island Studies, University of Prince Edward Island, Canada. -

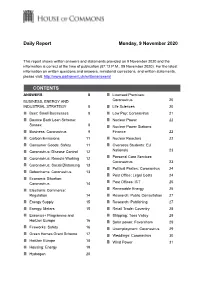

Daily Report Monday, 9 November 2020 CONTENTS

Daily Report Monday, 9 November 2020 This report shows written answers and statements provided on 9 November 2020 and the information is correct at the time of publication (07:12 P.M., 09 November 2020). For the latest information on written questions and answers, ministerial corrections, and written statements, please visit: http://www.parliament.uk/writtenanswers/ CONTENTS ANSWERS 8 Licensed Premises: BUSINESS, ENERGY AND Coronavirus 20 INDUSTRIAL STRATEGY 8 Life Sciences 20 Beer: Small Businesses 8 Low Pay: Coronavirus 21 Bounce Back Loan Scheme: Nuclear Power 22 Sussex 8 Nuclear Power Stations: Business: Coronavirus 9 Finance 22 Carbon Emissions 11 Nuclear Reactors 22 Consumer Goods: Safety 11 Overseas Students: EU Coronavirus: Disease Control 12 Nationals 23 Coronavirus: Remote Working 12 Personal Care Services: Coronavirus 23 Coronavirus: Social Distancing 13 Political Parties: Coronavirus 24 Debenhams: Coronavirus 13 Post Office: Legal Costs 24 Economic Situation: Coronavirus 14 Post Offices: ICT 25 Electronic Commerce: Renewable Energy 25 Regulation 14 Research: Public Consultation 27 Energy Supply 15 Research: Publishing 27 Energy: Meters 15 Retail Trade: Coventry 28 Erasmus+ Programme and Shipping: Tees Valley 28 Horizon Europe 16 Solar power: Faversham 29 Fireworks: Safety 16 Unemployment: Coronavirus 29 Green Homes Grant Scheme 17 Weddings: Coronavirus 30 Horizon Europe 18 Wind Power 31 Housing: Energy 19 Hydrogen 20 CABINET OFFICE 31 Musicians: Coronavirus 44 Ballot Papers: Visual Skateboarding: Coronavirus 44 Impairment 31 -

Draft Recommendations on the New Electoral Arrangements for Havering Council

Draft recommendations on the new electoral arrangements for Havering Council Electoral review July 2020 Translations and other formats: To get this report in another language or in a large-print or Braille version, please contact the Local Government Boundary Commission for England at: Tel: 0330 500 1525 Email: [email protected] Licensing: The mapping in this report is based upon Ordnance Survey material with the permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of the Keeper of Public Records © Crown copyright and database right. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown copyright and database right. Licence Number: GD 100049926 2020 A note on our mapping: The maps shown in this report are for illustrative purposes only. Whilst best efforts have been made by our staff to ensure that the maps included in this report are representative of the boundaries described by the text, there may be slight variations between these maps and the large PDF map that accompanies this report, or the digital mapping supplied on our consultation portal. This is due to the way in which the final mapped products are produced. The reader should therefore refer to either the large PDF supplied with this report or the digital mapping for the true likeness of the boundaries intended. The boundaries as shown on either the large PDF map or the digital mapping should always appear identical. Contents Introduction 1 Who we are and what we do 1 What is an electoral review? 1 Why Havering? 2 Our proposals for Havering 2 How will the recommendations affect you? 2 Have your -

Report on the Affairs of Phoenix Venture Holdings Limited, Mg Rover Group Limited and 33 Other Companies Volume I

REPORT ON THE AFFAIRS OF PHOENIX VENTURE HOLDINGS LIMITED, MG ROVER GROUP LIMITED AND 33 OTHER COMPANIES VOLUME I Gervase MacGregor FCA Guy Newey QC (Inspectors appointed by the Secretary of State for Trade and Industry under section 432(2) of the Companies Act 1985) Report on the affairs of Phoenix Venture Holdings Limited, MG Rover Group Limited and 33 other companies by Gervase MacGregor FCA and Guy Newey QC (Inspectors appointed by the Secretary of State for Trade and Industry under section 432(2) of the Companies Act 1985) Volume I Published by TSO (The Stationery Office) and available from: Online www.tsoshop.co.uk Mail, Telephone, Fax & E-mail TSO PO Box 29, Norwich, NR3 1GN Telephone orders/General enquiries: 0870 600 5522 Fax orders: 0870 600 5533 E-mail: [email protected] Textphone 0870 240 3701 TSO@Blackwell and other Accredited Agents Customers can also order publications from: TSO Ireland 16 Arthur Street, Belfast BT1 4GD Tel 028 9023 8451 Fax 028 9023 5401 Published with the permission of the Department for Business Innovation and Skills on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. © Crown Copyright 2009 All rights reserved. Copyright in the typographical arrangement and design is vested in the Crown. Applications for reproduction should be made in writing to the Office of Public Sector Information, Information Policy Team, Kew, Richmond, Surrey, TW9 4DU. First published 2009 ISBN 9780 115155239 Printed in the United Kingdom by the Stationery Office N6187351 C3 07/09 Contents Chapter Page VOLUME -

THE 422 Mps WHO BACKED the MOTION Conservative 1. Bim

THE 422 MPs WHO BACKED THE MOTION Conservative 1. Bim Afolami 2. Peter Aldous 3. Edward Argar 4. Victoria Atkins 5. Harriett Baldwin 6. Steve Barclay 7. Henry Bellingham 8. Guto Bebb 9. Richard Benyon 10. Paul Beresford 11. Peter Bottomley 12. Andrew Bowie 13. Karen Bradley 14. Steve Brine 15. James Brokenshire 16. Robert Buckland 17. Alex Burghart 18. Alistair Burt 19. Alun Cairns 20. James Cartlidge 21. Alex Chalk 22. Jo Churchill 23. Greg Clark 24. Colin Clark 25. Ken Clarke 26. James Cleverly 27. Thérèse Coffey 28. Alberto Costa 29. Glyn Davies 30. Jonathan Djanogly 31. Leo Docherty 32. Oliver Dowden 33. David Duguid 34. Alan Duncan 35. Philip Dunne 36. Michael Ellis 37. Tobias Ellwood 38. Mark Field 39. Vicky Ford 40. Kevin Foster 41. Lucy Frazer 42. George Freeman 43. Mike Freer 44. Mark Garnier 45. David Gauke 46. Nick Gibb 47. John Glen 48. Robert Goodwill 49. Michael Gove 50. Luke Graham 51. Richard Graham 52. Bill Grant 53. Helen Grant 54. Damian Green 55. Justine Greening 56. Dominic Grieve 57. Sam Gyimah 58. Kirstene Hair 59. Luke Hall 60. Philip Hammond 61. Stephen Hammond 62. Matt Hancock 63. Richard Harrington 64. Simon Hart 65. Oliver Heald 66. Peter Heaton-Jones 67. Damian Hinds 68. Simon Hoare 69. George Hollingbery 70. Kevin Hollinrake 71. Nigel Huddleston 72. Jeremy Hunt 73. Nick Hurd 74. Alister Jack (Teller) 75. Margot James 76. Sajid Javid 77. Robert Jenrick 78. Jo Johnson 79. Andrew Jones 80. Gillian Keegan 81. Seema Kennedy 82. Stephen Kerr 83. Mark Lancaster 84. -

Brexit: Initial Reflections

Brexit: initial reflections ANAND MENON AND JOHN-PAUL SALTER* At around four-thirty on the morning of 24 June 2016, the media began to announce that the British people had voted to leave the European Union. As the final results came in, it emerged that the pro-Brexit campaign had garnered 51.9 per cent of the votes cast and prevailed by a margin of 1,269,501 votes. For the first time in its history, a member state had voted to quit the EU. The outcome of the referendum reflected the confluence of several long- term and more contingent factors. In part, it represented the culmination of a longstanding tension in British politics between, on the one hand, London’s relative effectiveness in shaping European integration to match its own prefer- ences and, on the other, political diffidence when it came to trumpeting such success. This paradox, in turn, resulted from longstanding intraparty divisions over Britain’s relationship with the EU, which have hamstrung such attempts as there have been to make a positive case for British EU membership. The media found it more worthwhile to pour a stream of anti-EU invective into the resulting vacuum rather than critically engage with the issue, let alone highlight the benefits of membership. Consequently, public opinion remained lukewarm at best, treated to a diet of more or less combative and Eurosceptic political rhetoric, much of which disguised a far different reality. The result was also a consequence of the referendum campaign itself. The strategy pursued by Prime Minister David Cameron—of adopting a critical stance towards the EU, promising a referendum, and ultimately campaigning for continued membership—failed. -

Directions for Britain Outside the Eu Ralph Buckle • Tim Hewish • John C

BREXIT DIRECTIONS FOR BRITAIN OUTSIDE THE EU RALPH BUCKLE • TIM HEWISH • JOHN C. HULSMAN IAIN MANSFIELD • ROBERT OULDS BREXIT: Directions for Britain Outside the EU BREXIT: DIRECTIONS FOR BRITAIN OUTSIDE THE EU RALPH BUCKLE TIM HEWISH JOHN C. HULSMAN IAIN MANSFIELD ROBERT OULDS First published in Great Britain in 2015 by The Institute of Economic Affairs 2 Lord North Street Westminster London SW1P 3LB in association with London Publishing Partnership Ltd www.londonpublishingpartnership.co.uk The mission of the Institute of Economic Affairs is to improve understanding of the fundamental institutions of a free society by analysing and expounding the role of markets in solving economic and social problems. Copyright © The Institute of Economic Affairs 2015 The moral right of the author has been asserted. All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photo- copying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978-0-255-36682-3 (interactive PDF) Many IEA publications are translated into languages other than English or are reprinted. Permission to translate or to reprint should be sought from the Director General at the address above. Typeset in Kepler by T&T Productions Ltd www.tandtproductions.com -

Download (9MB)

A University of Sussex PhD thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details 2018 Behavioural Models for Identifying Authenticity in the Twitter Feeds of UK Members of Parliament A CONTENT ANALYSIS OF UK MPS’ TWEETS BETWEEN 2011 AND 2012; A LONGITUDINAL STUDY MARK MARGARETTEN Mark Stuart Margaretten Submitted for the degree of Doctor of PhilosoPhy at the University of Sussex June 2018 1 Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................................................................................................ 1 DECLARATION .................................................................................................................................. 4 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ...................................................................................................................... 5 FIGURES ........................................................................................................................................... 6 TABLES ............................................................................................................................................ -

New Ministerial Team at the Department of Health

New Ministerial Team at the Department of Health The Rt Hon Alan Johnson MP Secretary of State for Health Alan Johnson was first elected to Parliament in 1997 as the Member for Kingston upon Hull. A former postman, Alan Johnson served as a former General Secretary of the Communication Workers Union (CWU) and is one of the largest trade union names to have entered Parliament in recent decades. Often credited with the much coveted tag of being an "ordinary bloke", he is highly articulate and effective and is credited with the successful campaign that deterred the previous Conservative government from privatising the Post Office. Popular among his peers, Alan Johnson is generally regarded to be on the centre right of the Labour Party and is well regarded by the Labour leadership. As a union member of Labour's ruling NEC (up to 1996) he was seen as supportive of Tony Blair's attempts to modernise the Labour Party. He was the only senior union leader to back the abolition of Labour's clause IV. He becomes the first former union leader to become a cabinet minister in nearly 40 years when he is appointed to the Work and Pensions brief in 2004. After moving to Trade and Industry, he becomes Education and Skills Secretary in May 2006. After being tipped by many as the front-runner in the Labour deputy leadership contest of 2007, Alan Johnson was narrowly beaten by Harriet Harman. Commons Career PPS to Dawn Primarolo: as Financial Secretary, HM Treasury 1997-99, as Paymaster General, HM Treasury 1999; Department of Trade and Industry 1999-2003: -

Labour's Next Majority Means Winning Over Conservative Voters but They Are Not Likely to Be the Dominant Source of The

LABOUR’S NEXT MAJORITY THE 40% STRATEGY Marcus Roberts LABOUR’S The 40% There will be voters who go to the polls on 6th May 2015 who weren’t alive strategy when Tony and Cherie Blair posed outside 10 Downing Street on 1st May NEXT 1997. They will have no memory of an event which is a moment of history as distant from them as Margaret Thatcher’s 1979 election victory was for the voters of 1997. If Ed Miliband seeks to emulate what Blair did in 1997, he too must build his own political majority for the era in which he seeks to govern. MAJORITY This report sets out a plausible strategy for Labour’s next majority, one that is secured through winning 40 per cent of the popular vote in May 2015, despite the challenges of a fragmenting electorate. It also challenges the Marcus Roberts party at all levels to recognise that the 40 per cent strategy for a clear majority in 2015 will require a different winning formula to that which served New Labour so well a generation ago, but which is past its sell-by date in a different political and economic era. A FABIAN REPORT ISBN 978 0 7163 7004 8 ABOUT THE FABIAN SOCIETY The Fabian Society is Britain’s oldest political think tank. Since 1884 the society has played a central role in developing political ideas and public policy on the left. It aims to promote greater equality of wealth, power and opportunity; the value of collective public action; a vibrant, tolerant and accountable democracy; citizenship, liberty and human rights; sustainable development; and multilateral international cooperation. -

Daily Report Thursday, 29 April 2021 CONTENTS

Daily Report Thursday, 29 April 2021 This report shows written answers and statements provided on 29 April 2021 and the information is correct at the time of publication (04:42 P.M., 29 April 2021). For the latest information on written questions and answers, ministerial corrections, and written statements, please visit: http://www.parliament.uk/writtenanswers/ CONTENTS ANSWERS 11 Energy Intensive Industries: ATTORNEY GENERAL 11 Biofuels 18 Crown Prosecution Service: Environment Protection: Job Training 11 Creation 19 Sentencing: Appeals 11 EU Grants and Loans: Iron and Steel 19 BUSINESS, ENERGY AND INDUSTRIAL STRATEGY 12 Facebook: Advertising 20 Aviation and Shipping: Carbon Foreign Investment in UK: Budgets 12 National Security 20 Bereavement Leave 12 Help to Grow Scheme 20 Business Premises: Horizon Europe: Quantum Coronavirus 12 Technology and Space 21 Carbon Emissions 13 Horticulture: Job Creation 21 Clean Technology Fund 13 Housing: Natural Gas 21 Companies: West Midlands 13 Local Government Finance: Job Creation 22 Coronavirus: Vaccination 13 Members: Correspondence 22 Deep Sea Mining: Reviews 14 Modern Working Practices Economic Situation: Holiday Review 22 Leave 14 Overseas Aid: China 23 Electric Vehicles: Batteries 15 Park Homes: Energy Supply 23 Electricity: Billing 15 Ports: Scotland 24 Employment Agencies 16 Post Offices: ICT 24 Employment Agencies: Pay 16 Remote Working: Coronavirus 24 Employment Agency Standards Inspectorate and Renewable Energy: Finance 24 National Minimum Wage Research: Africa 25 Enforcement Unit 17 Summertime