Australian Acacia Species in South Africa As a Case Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Botanical Name: Acacia Common Name: Wattle Family: Fabaceae Origin: Australia and Africa Habit: Various Habitats Author: Diana Hughes, Mullumbimby

Botanical Name: Acacia Common Name: Wattle Family: Fabaceae Origin: Australia and Africa Habit: various habitats Author: Diana Hughes, Mullumbimby I like to turn to PlantNET-FloraOnline to learn more about plants. Here you will find a wealth of information about plants, their growing habits and distribution. Much can be learnt from Latin names given, plus the variety of common names attributed to each plant. A more familiar name for Acacia is Wattle - Australia's floral emblem, in this case Acacia pycantha, Golden Wattle, which is native to South Eastern Australia. We have beautiful wattles in our region, most of which are coming into flower now. Mullumbimby is famous for the rare Acacia bakeri, (Marblewood), a rainforest species. It is found on the banks of the Brunswick River, with insignificant white flowers, hidden in glossy leaves. Searches through several websites confirm my fears that many Acacias are considered as needing 'environmental management' - meaning they have weed potential. But who could find a field of beautiful Queensland Silver Wattle an unpleasant sight? Negatively they are 'seeders', and positively, they are nitrogen fixers. Managing the four species in my garden is a pleasure. My pride and joy is an Acacia macradenia, or Zig Zag wattle because its phyllodes (leaves) are arranged in that manner along weeping branches. It's about to flower for the 6th year. Motorists stop to photograph it as it is such a sight. I prune it hard each year. My rear raised garden bed holds 3 different species. The well-known Queensland Silver Wattle, or Mt Morgan wattle (Acacia podalyriifolia) is now flowering. -

Additional Information

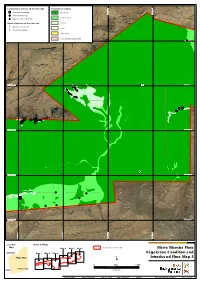

Current Survey Introduced Flora Records Vegetation Condition *Acetosa vesicaria Excellent 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 -

Wattles of the City of Whittlesea

Wattles of the City of Whittlesea PROTECTING BIODIVERSITY ON PRIVATE LAND SERIES Wattles of the City of Whittlesea Over a dozen species of wattle are indigenous to the City of Whittlesea and many other wattle species are commonly grown in gardens. Most of the indigenous species are commonly found in the forested hills and the native forests in the northern parts of the municipality, with some species persisting along country roadsides, in smaller reserves and along creeks. Wattles are truly amazing • Wattles have multiple uses for Australian plants indigenous peoples, with most species used for food, medicine • There are more wattle species than and/or tools. any other plant genus in Australia • Wattle seeds have very hard coats (over 1000 species and subspecies). which mean they can survive in the • Wattles, like peas, fix nitrogen in ground for decades, waiting for a the soil, making them excellent cool fire to stimulate germination. for developing gardens and in • Australia’s floral emblem is a wattle: revegetation projects. Golden Wattle (Acacia pycnantha) • Many species of insects (including and this is one of Whittlesea’s local some butterflies) breed only on species specific species of wattles, making • In Victoria there is at least one them a central focus of biodiversity. wattle species in flower at all times • Wattle seeds and the insects of the year. In the Whittlesea attracted to wattle flowers are an area, there is an indigenous wattle important food source for most bird in flower from February to early species including Black Cockatoos December. and honeyeaters. Caterpillars of the Imperial Blue Butterfly are only found on wattles RB 3 Basic terminology • ‘Wattle’ = Acacia Wattle is the common name and Acacia the scientific name for this well-known group of similar / related species. -

Supplementary Materialsupplementary Material

10.1071/BT13149_AC © CSIRO 2013 Australian Journal of Botany 2013, 61(6), 436–445 SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL Comparative dating of Acacia: combining fossils and multiple phylogenies to infer ages of clades with poor fossil records Joseph T. MillerA,E, Daniel J. MurphyB, Simon Y. W. HoC, David J. CantrillB and David SeiglerD ACentre for Australian National Biodiversity Research, CSIRO Plant Industry, GPO Box 1600 Canberra, ACT 2601, Australia. BRoyal Botanic Gardens Melbourne, Birdwood Avenue, South Yarra, Vic. 3141, Australia. CSchool of Biological Sciences, Edgeworth David Building, University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia. DDepartment of Plant Biology, University of Illinois, Urbana, IL 61801, USA. ECorresponding author. Email: [email protected] Table S1 Materials used in the study Taxon Dataset Genbank Acacia abbreviata Maslin 2 3 JF420287 JF420065 JF420395 KC421289 KC796176 JF420499 Acacia adoxa Pedley 2 3 JF420044 AF523076 AF195716 AF195684; AF195703 Acacia ampliceps Maslin 1 KC421930 EU439994 EU811845 Acacia anceps DC. 2 3 JF420244 JF420350 JF419919 JF420130 JF420456 Acacia aneura F.Muell. ex Benth 2 3 JF420259 JF420036 JF420366 JF419935 JF420146 KF048140 Acacia aneura F.Muell. ex Benth. 1 2 3 JF420293 JF420402 KC421323 JQ248740 JF420505 Acacia baeuerlenii Maiden & R.T.Baker 2 3 JF420229 JQ248866 JF420336 JF419909 JF420115 JF420448 Acacia beckleri Tindale 2 3 JF420260 JF420037 JF420367 JF419936 JF420147 JF420473 Acacia cochlearis (Labill.) H.L.Wendl. 2 3 KC283897 KC200719 JQ943314 AF523156 KC284140 KC957934 Acacia cognata Domin 2 3 JF420246 JF420022 JF420352 JF419921 JF420132 JF420458 Acacia cultriformis A.Cunn. ex G.Don 2 3 JF420278 JF420056 JF420387 KC421263 KC796172 JF420494 Acacia cupularis Domin 2 3 JF420247 JF420023 JF420353 JF419922 JF420133 JF420459 Acacia dealbata Link 2 3 JF420269 JF420378 KC421251 KC955787 JF420485 Acacia dealbata Link 2 3 KC283375 KC200761 JQ942686 KC421315 KC284195 Acacia deanei (R.T.Baker) M.B.Welch, Coombs 2 3 JF420294 JF420403 KC421329 KC955795 & McGlynn JF420506 Acacia dempsteri F.Muell. -

Acacia Saligna RA

Risk Assessment: ………….. ACACIA SALIGNA Prepared by: Etienne Branquart (1), Vanessa Lozano (2) and Giuseppe Brundu (2) (1) [[email protected]] (2) Department of Agriculture, University of Sassari, Italy [[email protected]] Date: first draft 01 st November 2017 Subsequently Reviewed by 2 independent external Peer Reviewers: Dr Rob Tanner, chosen for his expertise in Risk Assessments, and Dr Jean-Marc Dufor-Dror chosen for his expertise on Acacia saligna . Date: first revised version 04 th January 2018, revised in light of comments from independent expert Peer Reviewers. Approved by the IAS Scientific Forum on 26/10/2018 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 Branquart, Lozano & Brundu PRA Acacia saligna 8 9 10 Contents 11 Summary of the Express Pest Risk Assessment for Acacia saligna 4 12 Stage 1. Initiation 6 13 1.1 - Reason for performing the Pest Risk Assessment (PRA) 6 14 1.2 - PRA area 6 15 1.3 - PRA scheme 6 16 Stage 2. Pest risk assessment 7 17 2.1 - Taxonomy and identification 7 18 2.1.1 - Taxonomy 7 19 2.1.2 - Main synonyms 8 20 2.1.3 - Common names 8 21 2.1.4 - Main related or look-alike species 8 22 2.1.5 - Terminology used in the present PRA for taxa names 9 23 2.1.6 - Identification (brief description) 9 24 2.2 - Pest overview 9 25 2.2.2 - Habitat and environmental requirements 10 26 2.2.3 Resource acquisition mechanisms 12 27 2.2.4 - Symptoms 12 28 2.2.5 - Existing PRAs 12 29 Socio-economic benefits 13 30 2.3 - Is the pest a vector? 14 31 2.4 - Is a vector needed for pest entry or spread? 15 32 2.5 - Regulatory status of the pest 15 33 2.6 - Distribution -

Human-Mediated Introductions of Australian Acacias

Diversity and Distributions, (Diversity Distrib.) (2011) 17, 771–787 S EDITORIAL Human-mediated introductions of PECIAL ISSUE Australian acacias – a global experiment in biogeography 1 2 1 3,4 David M. Richardson *, Jane Carruthers , Cang Hui , Fiona A. C. Impson , :H Joseph T. Miller5, Mark P. Robertson1,6, Mathieu Rouget7, Johannes J. Le Roux1 and John R. U. Wilson1,8 UMAN 1 Centre for Invasion Biology, Department of ABSTRACT - Botany and Zoology, Stellenbosch University, MEDIATED INTRODUCTIONS OF Aim Australian acacias (1012 recognized species native to Australia, which were Matieland 7602, South Africa, 2Department of History, University of South Africa, PO Box previously grouped in Acacia subgenus Phyllodineae) have been moved extensively 392, Unisa 0003, South Africa, 3Department around the world by humans over the past 250 years. This has created the of Zoology, University of Cape Town, opportunity to explore how evolutionary, ecological, historical and sociological Rondebosch 7701, South Africa, 4Plant factors interact to affect the distribution, usage, invasiveness and perceptions of a Protection Research Institute, Private Bag globally important group of plants. This editorial provides the background for the X5017, Stellenbosch 7599, South Africa, 20 papers in this special issue of Diversity and Distributions that focusses on the 5Centre for Australian National Biodiversity global cross-disciplinary experiment of introduced Australian acacias. A Journal of Conservation Biogeography Research, CSIRO Plant Industry, GPO Box Location Australia and global. 1600, Canberra, ACT, Australia, 6Department of Zoology and Entomology, University of Methods The papers of the special issue are discussed in the context of a unified Pretoria, Pretoria 0002, South Africa, framework for biological invasions. -

Rail Development Vegetation and Flora Survey

JANUARY 2012 BROCKMAN RESOURCES LIMITED RAIL DEVELOPMENT VEGETATION AND FLORA SURVEY This page has been left blank intentionally BROCKMAN RESOURCES LIMITED RAIL DEVELOPMENT VEGETATION AND FLORA SURVEY Brockman Resources Limited Vegetation and Flora Survey Rail Corridor Document Status Approved for Issue Rev Author Reviewer Date Name Distributed To Date A Rochelle Renee 02/12/2011 Carol Macpherson Glenn Firth 02/12/2011 Haycock Tuckett Carol Macpherson B Carol 21.12.11 Carol Macpherson Glen Firth 23.12.11 Macpherson ecologia Environment (2011). Reproduction of this report in whole or in part by electronic, mechanical or chemical means including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, in any language, is strictly prohibited without the express approval of Brockman Resources Limited and/or ecologia Environment. Restrictions on Use This report has been prepared specifically for Brockman Resources Limited. Neither the report nor its contents may be referred to or quoted in any statement, study, report, application, prospectus, loan, or other agreement document, without the express approval of Brockman Resources Limited and/or ecologia Environment. ecologia Environment 1025 Wellington Street WEST PERTH WA 6005 Phone: 08 9322 1944 Fax: 08 9322 1599 Email: [email protected] December 2011 i Brockman Resources Limited Vegetation and Flora Survey Rail Corridor TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................ 1 -

The Invasion Ecology of Acacia Elata (A

The invasion ecology of Acacia elata (A. Cunn. Ex Benth.) with implications for the management of ornamental wattles by Jason Ernest Donaldson Thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Masters in the Faculty of Science at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Prof. David M. Richardson Co-supervisor: Dr. John R. Wilson December 2013 Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights, and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. September 2013 Copyright © 2013 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved i Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za Abstract This thesis explores how human dictated methods of introduction and species-specific traits interact to define spatial patterns in invasive plant populations using Acacia elata as a model species. I initially asked whether the relatively small invasive extent (when compared to congeners introduced for forestry or dune stabilization) of a species used widely for ornamental purposes (A. elata) is due to low rates of reproduction in South Africa. Results indicate that A. elata has similar traits to other invasive Australia Acacia species: annual seed input into the leaf litter was high (up to 5000 seeds m-2); large seedbanks develop (>20 000 seeds m-2) in established stands; seed germinability is very high (>90%); seeds accumulate mostly in the top soil layers but can infiltrate to depths of 40cm; and seed germination appears to be stimulated by fire. -

Native Plants Sixth Edition Sixth Edition AUSTRALIAN Native Plants Cultivation, Use in Landscaping and Propagation

AUSTRALIAN NATIVE PLANTS SIXTH EDITION SIXTH EDITION AUSTRALIAN NATIVE PLANTS Cultivation, Use in Landscaping and Propagation John W. Wrigley Murray Fagg Sixth Edition published in Australia in 2013 by ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Reed New Holland an imprint of New Holland Publishers (Australia) Pty Ltd Sydney • Auckland • London • Cape Town Many people have helped us since 1977 when we began writing the first edition of Garfield House 86–88 Edgware Road London W2 2EA United Kingdom Australian Native Plants. Some of these folk have regrettably passed on, others have moved 1/66 Gibbes Street Chatswood NSW 2067 Australia to different areas. We endeavour here to acknowledge their assistance, without which the 218 Lake Road Northcote Auckland New Zealand Wembley Square First Floor Solan Road Gardens Cape Town 8001 South Africa various editions of this book would not have been as useful to so many gardeners and lovers of Australian plants. www.newhollandpublishers.com To the following people, our sincere thanks: Steve Adams, Ralph Bailey, Natalie Barnett, www.newholland.com.au Tony Bean, Lloyd Bird, John Birks, Mr and Mrs Blacklock, Don Blaxell, Jim Bourner, John Copyright © 2013 in text: John Wrigley Briggs, Colin Broadfoot, Dot Brown, the late George Brown, Ray Brown, Leslie Conway, Copyright © 2013 in map: Ian Faulkner Copyright © 2013 in photographs and illustrations: Murray Fagg Russell and Sharon Costin, Kirsten Cowley, Lyn Craven (Petraeomyrtus punicea photograph) Copyright © 2013 New Holland Publishers (Australia) Pty Ltd Richard Cummings, Bert -

Evolution of Angiosperm Pollen. 7. Nitrogen-Fixing Clade1

Evolution of Angiosperm Pollen. 7. Nitrogen-Fixing Clade1 Authors: Jiang, Wei, He, Hua-Jie, Lu, Lu, Burgess, Kevin S., Wang, Hong, et. al. Source: Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden, 104(2) : 171-229 Published By: Missouri Botanical Garden Press URL: https://doi.org/10.3417/2019337 BioOne Complete (complete.BioOne.org) is a full-text database of 200 subscribed and open-access titles in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Complete website, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/terms-of-use. Usage of BioOne Complete content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non - commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Downloaded From: https://bioone.org/journals/Annals-of-the-Missouri-Botanical-Garden on 01 Apr 2020 Terms of Use: https://bioone.org/terms-of-use Access provided by Kunming Institute of Botany, CAS Volume 104 Annals Number 2 of the R 2019 Missouri Botanical Garden EVOLUTION OF ANGIOSPERM Wei Jiang,2,3,7 Hua-Jie He,4,7 Lu Lu,2,5 POLLEN. 7. NITROGEN-FIXING Kevin S. Burgess,6 Hong Wang,2* and 2,4 CLADE1 De-Zhu Li * ABSTRACT Nitrogen-fixing symbiosis in root nodules is known in only 10 families, which are distributed among a clade of four orders and delimited as the nitrogen-fixing clade. -

Indigenous Plants of Bendigo

Produced by Indigenous Plants of Bendigo Indigenous Plants of Bendigo PMS 1807 RED PMS 432 GREY PMS 142 GOLD A Gardener’s Guide to Growing and Protecting Local Plants 3rd Edition 9 © Copyright City of Greater Bendigo and Bendigo Native Plant Group Inc. This work is Copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the City of Greater Bendigo. First Published 2004 Second Edition 2007 Third Edition 2013 Printed by Bendigo Modern Press: www.bmp.com.au This book is also available on the City of Greater Bendigo website: www.bendigo.vic.gov.au Printed on 100% recycled paper. Disclaimer “The information contained in this publication is of a general nature only. This publication is not intended to provide a definitive analysis, or discussion, on each issue canvassed. While the Committee/Council believes the information contained herein is correct, it does not accept any liability whatsoever/howsoever arising from reliance on this publication. Therefore, readers should make their own enquiries, and conduct their own investigations, concerning every issue canvassed herein.” Front cover - Clockwise from centre top: Bendigo Wax-flower (Pam Sheean), Hoary Sunray (Marilyn Sprague), Red Ironbark (Pam Sheean), Green Mallee (Anthony Sheean), Whirrakee Wattle (Anthony Sheean). Table of contents Acknowledgements ...............................................2 Foreword..........................................................3 Introduction.......................................................4 -

The Vegetation of Granitic Outcrop Communities on the New England Batholith of Eastern Australia

547 The vegetation of granitic outcrop communities on the New England Batholith of eastern Australia John T. Hunter and Peter J. Clarke Hunter, John T. and Clarke, Peter J. (Division of Botany, University of New England, Armidale, NSW 2350) 1998. The vegetation of granitic outcrop communities on the New England Batholith of eastern Australia. Cunninghamia 5 (3): 547–618. The vegetation of 22 areas of granitic outcrops on the New England Batholith has been surveyed using semi-quantitative quadrat sampling. In total 399 0.1 ha quadrats were placed on 216 outcrops. Twenty-eight plant communities in nine major groups and an additional unsurveyed community are circumscribed. A high number of nationally rare or threatened taxa, many of which are restricted to outcrop areas, have been found in these communities along with many taxa of special note. Previous studies have over-emphasised structure which can vary considerably with negligible floristic change. Suggestions are made on potential areas for reservation. Introduction Studies concentrating on the vegetation of granitic outcrops have been undertaken throughout the world (e.g. Whitehouse 1933; Oosting & Anderson 1937; McVaugh 1943; Keever et al. 1951; Keever 1957; Hambler 1964; Murdy et al. 1970; Sharitz & McCormick 1973; Rundel 1975; Shure & Fagsdale 1977; Wyatt 1977; Phillips 1981; Phillips 1982; Wyatt 1981; Baskin & Baskin 1982; Walters 1982; Burbanck & Phillips 1983; Wyatt 1984a, b; Uno & Collins 1987; Baskin & Baskin 1988; Houle & Phillips 1988; Houle & Phillips 1989a, b; Houle 1990; Porembski et al. 1994; Ibisch et al. 1995; Porembski 1995; Porembski et al. 1996). Research into outcrops, and in particular granitic outcrops, has culminated in the formation of the ‘Inselberg-Projeckt’ supported by the Deutsche Forschungsge-meinschaft (Porembski et al.