Plant Invasion As an Emerging Challenge for the Conservation of Heritage Sites: the Spread of Ornamental Trees on Ancient Monuments in Rome, Italy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ailanthus Excelsa Roxb

Ailanthus excelsa Roxb. Simaroubaceae maharukh LOCAL NAMES Arabic (ailanthus,neem hindi); English (ailanthus,coramandel ailanto,tree- of-heaven); Gujarati (aduso,ardusi,bhutrakho); Hindi (maharuk,ardu,ardusi,arua,horanim maruk,aduso,mahanim,mahrukh,maruf,pedu,Pee vepachettu,pir nim); Nepali (maharukh); Sanskrit (madala); Tamil (periamaram,peru,perumaran,pimaram,pinari); Trade name (maharukh) BOTANIC DESCRIPTION Ailanthus excelsa is a large deciduous tree, 18-25 m tall; trunk straight, 60-80 cm in diameter; bark light grey and smooth, becoming grey-brown and rough on large trees, aromatic, slightly bitter. Leaves alternate, pinnately compound, large, 30-60 cm or more in length; leaflets 8-14 or more pairs, long stalked, ovate or broadly lance shaped from very unequal base, 6-10 cm long, 3-5 cm wide, often curved, long pointed, hairy gland; edges coarsely toothed and often lobed. Flower clusters droop at leaf bases, shorter than leaves, much branched; flowers many, mostly male and female on different trees, short stalked, greenish-yellow; calyx 5 lobed; 5 narrow petals spreading 6 mm across; stamens 10; on other flowers, 2-5 separate pistils, each with elliptical ovary, 1 ovule, and slender style. Fruit a 1-seeded samara, lance shaped, flat, pointed at ends, 5 cm long, 1 cm wide, copper red, strongly veined, twisted at the base The generic name ‘Ailanthus’ comes from ‘ailanthos’ (tree of heaven), the Indonesian name for Ailanthus moluccana. BIOLOGY The flowers appear in large open clusters among the leaves towards the end of the cold season. Male, female and bisexual flowers are intermingled on the same tree. The fruits ripen just before the onset of the monsoon. -

Plant Conservation Alliance®S Alien Plant Working Group Tree of Heaven Ailanthus Altissima (Mill.) Swingle Quassia Family (Sima

FACT SHEET: TREE OF HEAVEN Tree of Heaven Ailanthus altissima (Mill.) Swingle Quassia family (Simaroubaceae) NATIVE RANGE Central China DESCRIPTION Tree-of-heaven, also known as ailanthus, Chinese sumac, and stinking shumac, is a rapidly growing, deciduous tree in the mostly tropical quassia family (Simaroubaceae). Mature trees can reach 80 feet or more in height. Ailanthus has smooth stems with pale gray bark, and twigs which are light chestnut brown, especially in the dormant season. Its large compound leaves, 1-4 feet in length, are composed of 11-25 smaller leaflets and alternate along the stems. Each leaflet has one to several glandular teeth near the base. In late spring, clusters of small, yellow-green flowers appear near the tips of branches. Seeds are produced on female trees in late summer to early fall, in flat, twisted, papery structures called samaras, which may remain on the trees for long periods of time. The wood of ailanthus is soft, weak, coarse-grained, and creamy white to light brown in color. All parts of the tree, especially the flowers, have a strong, offensive odor, which some have likened to peanuts or cashews. NOTE: Correct identification of ailanthus is essential. Several native shrubs, like sumacs, and trees, like ash, black walnut and pecan, can be confused with ailanthus. Staghorn sumac (Rhus typhina), native to the eastern U.S., is distinguished from ailanthus by its fuzzy, reddish-brown branches and leaf stems, erect, red, fuzzy fruits, and leaflets with toothed margins. ECOLOGICAL THREAT Tree-of-heaven is a prolific seed producer, grows rapidly, and can overrun native vegetation. -

Brisbane Native Plants by Suburb

INDEX - BRISBANE SUBURBS SPECIES LIST Acacia Ridge. ...........15 Chelmer ...................14 Hamilton. .................10 Mayne. .................25 Pullenvale............... 22 Toowong ....................46 Albion .......................25 Chermside West .11 Hawthorne................. 7 McDowall. ..............6 Torwood .....................47 Alderley ....................45 Clayfield ..................14 Heathwood.... 34. Meeandah.............. 2 Queensport ............32 Trinder Park ...............32 Algester.................... 15 Coopers Plains........32 Hemmant. .................32 Merthyr .................7 Annerley ...................32 Coorparoo ................3 Hendra. .................10 Middle Park .........19 Rainworth. ..............47 Underwood. ................41 Anstead ....................17 Corinda. ..................14 Herston ....................5 Milton ...................46 Ransome. ................32 Upper Brookfield .......23 Archerfield ...............32 Highgate Hill. ........43 Mitchelton ...........45 Red Hill.................... 43 Upper Mt gravatt. .......15 Ascot. .......................36 Darra .......................33 Hill End ..................45 Moggill. .................20 Richlands ................34 Ashgrove. ................26 Deagon ....................2 Holland Park........... 3 Moorooka. ............32 River Hills................ 19 Virginia ........................31 Aspley ......................31 Doboy ......................2 Morningside. .........3 Robertson ................42 Auchenflower -

Moths of Ohio Guide

MOTHS OF OHIO field guide DIVISION OF WILDLIFE This booklet is produced by the ODNR Division of Wildlife as a free publication. This booklet is not for resale. Any unauthorized INTRODUCTION reproduction is prohibited. All images within this booklet are copyrighted by the Division of Wildlife and it’s contributing artists and photographers. For additional information, please call 1-800-WILDLIFE. Text by: David J. Horn Ph.D Moths are one of the most diverse and plentiful HOW TO USE THIS GUIDE groups of insects in Ohio, and the world. An es- Scientific Name timated 160,000 species have thus far been cata- Common Name Group and Family Description: Featured Species logued worldwide, and about 13,000 species have Secondary images 1 Primary Image been found in North America north of Mexico. Secondary images 2 Occurrence We do not yet have a clear picture of the total Size: when at rest number of moth species in Ohio, as new species Visual Index Ohio Distribution are still added annually, but the number of species Current Page Description: Habitat & Host Plant is certainly over 3,000. Although not as popular Credit & Copyright as butterflies, moths are far more numerous than their better known kin. There is at least twenty Compared to many groups of animals, our knowledge of moth distribution is very times the number of species of moths in Ohio as incomplete. Many areas of the state have not been thoroughly surveyed and in some there are butterflies. counties hardly any species have been documented. Accordingly, the distribution maps in this booklet have three levels of shading: 1. -

Samia Cynthia in New Jersey Book Review, Market- Place, Metamorphosis, Announcements, Membership Updates

________________________________________________________________________________________ Volume 61, Number 4 Winter 2019 www.lepsoc.org ________________________________________________________________________________________ Inside: Butterflies of Papua Southern Pearly Eyes in exotic Louisiana venue Philippine butterflies and moths: a new website The Lepidopterists’ Society collecting statement updated Lep Soc, Southern Lep Soc, and Assoc of Trop Lep combined meeting Butterfly vicariance in southeast Asia Samia cynthia in New Jersey Book Review, Market- place, Metamorphosis, Announcements, Membership Updates ... and more! ________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________ Contents www.lepsoc.org ________________________________________________________ Digital Collecting -- Butterflies of Papua, Indonesia ____________________________________ Bill Berthet. .......................................................................................... 159 Volume 61, Number 4 Butterfly vicariance in Southeast Asia Winter 2019 John Grehan. ........................................................................................ 168 Metamorphosis. ....................................................................................... 171 The Lepidopterists’ Society is a non-profit ed- Membership Updates. ucational and scientific organization. The ob- Chris Grinter. ....................................................................................... 171 -

Ailanthus Altissima)

BEST MANAGEMENT PRACTICES LOWER HUDSON VALLEY PRISM HUDSONIA FOR INVASIVE PLANTS TREE-OF-HEAVEN (Ailanthus altissima) Bark of a medium-sized tree © E. Kiviat Kiviat Each leaflet has one or a few rounded teeth near its base, and a thickened, round gland on the underside of each tooth University of Tennessee Herbarium, Knoxville http://tenn.bio.utk.edu/ © E. Kiviat Kiviat A fast-growing tree to 20 m with large, odor (likened to stale peanut butter) when compound leaves composed of 10-40 leaflets. crushed. In summer and fall, large drooping Leaves and stems have a strong, unpleasant clusters of winged seeds are visible. Native to central China and Taiwan, tree-of-heaven is now invasive around the world. In the US, it became widely available to gardeners in the 1820s and is now most abundant in the East, Upper Midwest, Pacific Northwest, and California. Similar species: Several sumac (Rhus) species are most similar to tree-of-heaven. It can be distinguished from sumac as well as other trees with compound leaves by the presence of glands near the base of each leaflet. Also, tree-of-heaven has clear sap, while that of sumac is milky and sticky. Ashes (Fraxinus) have opposite leaves, and walnut and butternut (Juglans) leaflets are evenly toothed along the margins. Tree-of-heaven has a unique odor when bruised. BEST MANAGEMENT PRACTICES FOR INVASIVE PLANTS -- LOWER HUDSON VALLEY PRISM -- HUDSONIA Tree-of-heaven Where found: Tree-of-heaven is shade-intolerant, and usually found in open areas with disturbed, mineral soils.1 It can grow in a wide range of soil types and conditions, and is tolerant of drought and most industrial pollutants. -

Assessing Potential Biological Control of the Invasive Plant, Tree-Of-Heaven, Ailanthus Altissima

This article was downloaded by: [USDA National Agricultural Library] On: 11 August 2009 Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 741288003] Publisher Taylor & Francis Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Biocontrol Science and Technology Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713409232 Assessing potential biological control of the invasive plant, tree-of-heaven, Ailanthus altissima Jianqing Ding a; Yun Wu b; Hao Zheng a; Weidong Fu a; Richard Reardon b; Min Liu a a Institute of Biological Control, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Beijing, P.R. China b Forest Health Technology Enterprise Team, USDA Forest Service, Morgantown, USA Online Publication Date: 01 June 2006 To cite this Article Ding, Jianqing, Wu, Yun, Zheng, Hao, Fu, Weidong, Reardon, Richard and Liu, Min(2006)'Assessing potential biological control of the invasive plant, tree-of-heaven, Ailanthus altissima',Biocontrol Science and Technology,16:6,547 — 566 To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/09583150500531909 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09583150500531909 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. -

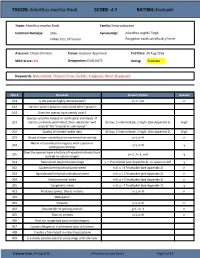

TAXON:Ailanthus Excelsa Roxb. SCORE:4.0 RATING:Evaluate

TAXON: Ailanthus excelsa Roxb. SCORE: 4.0 RATING: Evaluate Taxon: Ailanthus excelsa Roxb. Family: Simaroubaceae Common Name(s): ardu Synonym(s): Ailanthus wightii Tiegh. Indian tree of heaven Pongelion excelsum (Roxb.) Pierre Assessor: Chuck Chimera Status: Assessor Approved End Date: 24 Aug 2016 WRA Score: 4.0 Designation: EVALUATE Rating: Evaluate Keywords: Naturalized, Tropical Tree, Fodder, Coppices, Wind-Dispersed Qsn # Question Answer Option Answer 101 Is the species highly domesticated? y=-3, n=0 n 102 Has the species become naturalized where grown? 103 Does the species have weedy races? Species suited to tropical or subtropical climate(s) - If 201 island is primarily wet habitat, then substitute "wet (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2-high) (See Appendix 2) High tropical" for "tropical or subtropical" 202 Quality of climate match data (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2-high) (See Appendix 2) High 203 Broad climate suitability (environmental versatility) y=1, n=0 n Native or naturalized in regions with tropical or 204 y=1, n=0 y subtropical climates Does the species have a history of repeated introductions 205 y=-2, ?=-1, n=0 y outside its natural range? 301 Naturalized beyond native range y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2), n= question 205 y 302 Garden/amenity/disturbance weed n=0, y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2) n 303 Agricultural/forestry/horticultural weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see Appendix 2) n 304 Environmental weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see Appendix 2) n 305 Congeneric weed n=0, y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2) y 401 Produces spines, thorns or burrs y=1, n=0 n 402 Allelopathic 403 Parasitic y=1, n=0 n 404 Unpalatable to grazing animals y=1, n=-1 n 405 Toxic to animals y=1, n=0 n 406 Host for recognized pests and pathogens 407 Causes allergies or is otherwise toxic to humans 408 Creates a fire hazard in natural ecosystems 409 Is a shade tolerant plant at some stage of its life cycle Creation Date: 24 Aug 2016 (Ailanthus excelsa Roxb.) Page 1 of 17 TAXON: Ailanthus excelsa Roxb. -

Effectiveness of Ailanthus Altissima As a Bioindicator of Ozone Pollution

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School The Huck Institutes of the Life Sciences EFFECTIVENESS OF AILANTHUS ALTISSIMA AS A BIOINDICATOR OF OZONE POLLUTION A Thesis in Ecology by Lauren K. Seiler © 2012 Lauren K. Seiler Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science August 2012 The thesis of Lauren K Seiler was reviewed and approved* by the following: Dennis R. Decoteau Professor of Horticulture and Plant Ecosystem Health Thesis Adviser Donald D. Davis Professor of Plant Pathology Margot W. Kaye Assistant Professor of Forest Ecology David M. Eissenstat Professor of Woody Plant Physiology Chair of Intercollege Graduate Degree Program in Ecology *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School. ii Abstract Ground-level ozone is one of the most significant air pollutants in the US; it is harmful to human health, vegetation, and ecosystems. Concurrently, Ailanthus altissima (tree-of-heaven, Ailanthus) is one of the most invasive plant species in the US. A series of exposure experiments and field surveys were conducted during 2010 and 2011 to evaluate the effectiveness of Ailanthus as a bioindicator of ozone pollution. To explore the uniformity of Ailanthus’ reaction to ozone, Ailanthus seedlings from 6 locations (Reno, NV; Corvallis, OR; Bloomington, IN; Mineral, VA; State College, PA; and Far Rockaway, NY) were exposed to ozone using continuously stirred tank reactor chambers within a greenhouse. Seedlings from the Corvallis, OR seed source were planted in the field and monitored for ambient ozone-induced foliar injury along with staghorn sumac, black cherry, common milkweed, and dogbane to evaluate Ailanthus’ performance compared to other ozone bioindicators. -

Ailanthus SP.Indd

AILANTHUS Science Page DID YOU KNOW? THE AILANTHUS PLANT .usbg.gov Ailanthus trees grow rapidly, and can reach w Ailanthus can grow in places where 25 meters (80 ft) or more in height. ww almost nothing else All parts of the plant, but will grow. It can especially the flowers, have a strong smell. even grow out of cracks in sidewalks In spring, yellow flowers in polluted cities. appear at the tips of the branches. Male and female flowers are on different trees. male The roots flower UNITEDSTATES BOTANIC GARDEN ORIGINS exude a chemical that Ailanthus is a female hinders the flower native of China. growth of In the US, it was other plants. In summer first planted in and early fall, Philadelphia in The leaves are large clusters of red 1784. It was with pointed leaflets. fruits ripen a popular tree on the female trees. One tree among urban can produce gardeners because thousands of A cluster of its large, fruits each of fruit is year, which are beautiful leaves, rapid growth, and hardiness. Each fruit blown by the 15-30 cm Now the plant is considered a weedy pest 30-60 cm has one (6-12 in) (12-24 in) wind to new seed. long. because it quickly takes over new areas. growing places. CLASSIFYING AILANTHUS FAMILY GENUS SPECIES Simaroubaceae (Quassia family) Ailanthus altissima There are about 150 members in this family. There are about 10 species in “Altissima” is Latin for Most are tropical trees and shrubs. The common name for this genus, all native to Asia “tallest.” Ailanthus grows and Australia. -

Ailanthus Altissima Tree-Of-Heaven1 Edward F

Fact Sheet ST-67 November 1993 Ailanthus altissima Tree-of-Heaven1 Edward F. Gilman and Dennis G. Watson2 INTRODUCTION This non-native deciduous tree will rapidly grow to 70 to 100 feet in height and produces an open canopy of stout branches covered with one to three- foot-long, pinnately compound, dark green leaves (Fig. 1). Broken stems smell of rancid peanut butter, and males reportedly smell worse than female trees. The leaves turn only slightly yellow in fall before dropping. The small, green, male and female flowers are produced on separate trees and appear in dense, terminal clusters. The 1.5-inch-long, yellow to red/brown, winged fruits which follow the blossoms will persist on the tree in dense clusters throughout the fall and into the winter months, and are quite attractive. They can create a crunchy mess when they fall to the ground. Seeds sprout easily and seedlings usually invade surrounding land. Figure 1. Mature Tree-of-Heaven. GENERAL INFORMATION DESCRIPTION Scientific name: Ailanthus altissima Height: 60 to 75 feet Pronunciation: ay-LANTH-us al-TISS-sim-muh Spread: 35 to 50 feet Common name(s): Tree-of-Heaven Crown uniformity: irregular outline or silhouette Family: Simaroubaceae Crown shape: upright USDA hardiness zones: 5 through 8A (Fig. 2) Crown density: open Origin: not native to North America Growth rate: fast Uses: reclamation plant Texture: coarse Availability: grown in small quantities by a small number of nurseries Foliage Leaf arrangement: alternate (Fig. 3) Leaf type: even pinnately compound Leaflet margin: ciliate Leaflet shape: ovate 1. This document is adapted from Fact Sheet ST-67, a series of the Environmental Horticulture Department, Florida Cooperative Extension Service, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, University of Florida. -

Ailanthus Altissima (Simaroubaceae) Web Resources: Ailanthus: a Nonnative Urban Tree Fromforested and Non-Forested Sites

US FOREST SERVICE NORTHERN RESEARCH STATION Research Review NO. 22 | SPRING 2014 Mycorrhizal associations in Ailanthus altissima (Simaroubaceae) Web Resources: Ailanthus: A Nonnative Urban Tree fromforested and non-forested sites. Journal of the Torrey USDA National Invasive Species Information Center: Botanical Society 134(1): 27-33. www.invasivespeciesinfo.gov/ Is Causing Trouble in Our Forests Patterns shtml Nonnative Ailanthus, the so-called tree-of-heaven, is probably the most famous invasive tree in In: Laband the United States. It’s the title tree in Betty Smith’s classic 1943 novel A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, where it is used as a metaphor for persistence and toughness in the face of nnis/ adversity. However, that toughness makes this tree—Ailanthus altissima (aka ailanthus, tree-of-heaven, stink tree, and Chinese sumac)—a serious problem wherever it grows. It usually grows in urban settings, industrial wastelands, and mine spoils, and along railroad and highway corridors. It survives in hot, dry, and toxic soils, and sends down its roots around and through concrete and paving cracks. It sends out seeds in enormous htm numbers, smells bad, and is allelopathic (toxic to other plants). Ailanthus can create Verticillium nonalfalfae dense clonal thickets, almost monocultures. It grows very quickly, often displacing native and other hosts. plants, which may affect wildlife. It is extremely difficult to eradicate, and cutting down the trunk and/or pesticide treatment only result in new shoots growing up from the roots. pdf Botanists, ecologists, and foresters plus forest owners and managers have realized that ailanthus has now spread into eastern forests and is endangering regeneration and restoration efforts, especially in the mixed-oak forests of West Virginia, Ohio, and tree Pennsylvania.