Ailanthus Altissima)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interaction Between Ailanthus Altissima and Native Robinia Pseudoacacia in Early Succession: Implications for Forest Management

Article Interaction between Ailanthus altissima and Native Robinia pseudoacacia in Early Succession: Implications for Forest Management Erik T. Nilsen 1,* ID , Cynthia D. Huebner 2, David E. Carr 3 and Zhe Bao 1 1 Department of Biological Sciences, 3002 Derring Hall, 1405 Perry Street, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, VA 24061, USA; [email protected] 2 US Department of Agriculture Forest Service, Northern Research Station, Morgantown, WV 26505, USA; [email protected] 3 Department of Environmental Sciences, University of Virginia, Blandy Experimental Farm, 400 Blandy Farm Lane, Boyce, VA 22620, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-540-231-5674; Fax: +1-540-231-9307 Received: 12 March 2018; Accepted: 17 April 2018; Published: 20 April 2018 Abstract: The goal of this study was to discover the nature and intensity of the interaction between an exotic invader Ailanthus altissima (Mill.) Swingle and its coexisting native Robinia pseudoacacia L. and consider management implications. The study occurred in the Mid-Appalachian region of the eastern United States. Ailanthus altissima can have a strong negative influence on community diversity and succession due to its allelopathic nature while R. pseudoacacia can have a positive effect on community diversity and succession because of its ability to fix nitrogen. How these trees interact and the influence of the interaction on succession will have important implications for forests in many regions of the world. An additive-replacement series common garden experiment was established to identify the type and extent of interactions between these trees over a three-year period. Both A. altissima and R. -

Effects of Ailanthus Altissima Soil Leachates on Nodulation and Expression of Two Genes That Regulate Nodulation of Trifolium Pr

Grand Valley State University ScholarWorks@GVSU Masters Theses Graduate Research and Creative Practice 4-2012 Effects of Ailanthus altissima Soil Leachates on Nodulation and Expression of Two Genes that Regulate Nodulation of Trifolium pratense Jesse Michael Lincoln Grand Valley State University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/theses Part of the Biology Commons Recommended Citation Lincoln, Jesse Michael, "Effects of Ailanthus altissima Soil Leachates on Nodulation and Expression of Two Genes that Regulate Nodulation of Trifolium pratense" (2012). Masters Theses. 13. http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/theses/13 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research and Creative Practice at ScholarWorks@GVSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@GVSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Effects of Ailanthus altissima soil leachates on nodulation and expression of two genes that regulate nodulation of Trifolium pratense Jesse Michael Lincoln A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of GRAND VALLEY STATE UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Masters of Science Department of Biology April 2012 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my advisors Gary Greer, Ph.D. and Margaret Dietrich, Ph.D. for their guidance and assistance throughout my graduate experience. My third committee member, Ryan Thum, Ph.D., also provided valuable guidance in shaping this project. I received -

Ailanthus Excelsa Roxb

Ailanthus excelsa Roxb. Simaroubaceae maharukh LOCAL NAMES Arabic (ailanthus,neem hindi); English (ailanthus,coramandel ailanto,tree- of-heaven); Gujarati (aduso,ardusi,bhutrakho); Hindi (maharuk,ardu,ardusi,arua,horanim maruk,aduso,mahanim,mahrukh,maruf,pedu,Pee vepachettu,pir nim); Nepali (maharukh); Sanskrit (madala); Tamil (periamaram,peru,perumaran,pimaram,pinari); Trade name (maharukh) BOTANIC DESCRIPTION Ailanthus excelsa is a large deciduous tree, 18-25 m tall; trunk straight, 60-80 cm in diameter; bark light grey and smooth, becoming grey-brown and rough on large trees, aromatic, slightly bitter. Leaves alternate, pinnately compound, large, 30-60 cm or more in length; leaflets 8-14 or more pairs, long stalked, ovate or broadly lance shaped from very unequal base, 6-10 cm long, 3-5 cm wide, often curved, long pointed, hairy gland; edges coarsely toothed and often lobed. Flower clusters droop at leaf bases, shorter than leaves, much branched; flowers many, mostly male and female on different trees, short stalked, greenish-yellow; calyx 5 lobed; 5 narrow petals spreading 6 mm across; stamens 10; on other flowers, 2-5 separate pistils, each with elliptical ovary, 1 ovule, and slender style. Fruit a 1-seeded samara, lance shaped, flat, pointed at ends, 5 cm long, 1 cm wide, copper red, strongly veined, twisted at the base The generic name ‘Ailanthus’ comes from ‘ailanthos’ (tree of heaven), the Indonesian name for Ailanthus moluccana. BIOLOGY The flowers appear in large open clusters among the leaves towards the end of the cold season. Male, female and bisexual flowers are intermingled on the same tree. The fruits ripen just before the onset of the monsoon. -

Plant Conservation Alliance®S Alien Plant Working Group Tree of Heaven Ailanthus Altissima (Mill.) Swingle Quassia Family (Sima

FACT SHEET: TREE OF HEAVEN Tree of Heaven Ailanthus altissima (Mill.) Swingle Quassia family (Simaroubaceae) NATIVE RANGE Central China DESCRIPTION Tree-of-heaven, also known as ailanthus, Chinese sumac, and stinking shumac, is a rapidly growing, deciduous tree in the mostly tropical quassia family (Simaroubaceae). Mature trees can reach 80 feet or more in height. Ailanthus has smooth stems with pale gray bark, and twigs which are light chestnut brown, especially in the dormant season. Its large compound leaves, 1-4 feet in length, are composed of 11-25 smaller leaflets and alternate along the stems. Each leaflet has one to several glandular teeth near the base. In late spring, clusters of small, yellow-green flowers appear near the tips of branches. Seeds are produced on female trees in late summer to early fall, in flat, twisted, papery structures called samaras, which may remain on the trees for long periods of time. The wood of ailanthus is soft, weak, coarse-grained, and creamy white to light brown in color. All parts of the tree, especially the flowers, have a strong, offensive odor, which some have likened to peanuts or cashews. NOTE: Correct identification of ailanthus is essential. Several native shrubs, like sumacs, and trees, like ash, black walnut and pecan, can be confused with ailanthus. Staghorn sumac (Rhus typhina), native to the eastern U.S., is distinguished from ailanthus by its fuzzy, reddish-brown branches and leaf stems, erect, red, fuzzy fruits, and leaflets with toothed margins. ECOLOGICAL THREAT Tree-of-heaven is a prolific seed producer, grows rapidly, and can overrun native vegetation. -

12 Different Types of Pollination Agents And

Advances in Biology & Earth Sciences Vol.4, No.1, 2019, pp.12-25 DIFFERENT TYPES OF POLLINATION AGENTS AND INVASIVE PLANTS PHENOLOGY AS A VECTOR OF INVASIVENESS Senka Barudanović1,2, Emina Zečić1,2*, Mašić Ermin1,2 1University of Sarajevo, Faculty of Science, Department of Biology, Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina 2Centre for Ecology and Natural Resources - Academician Sulejman Redžić, Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina Abstract. The phenology patterns of invasive plants and other plants in weed communities were studied in the central part of Bosnia and Herzegovina, in the area of Zenica town which has been under the strong anthropogenic influence for decades. The phenology of invasive plant species was analyzed and compared with the phenology of other, non-invasive plants within the examined weed communities. The phytocoenological research was conducted on selected control points by means of standard Zurich- Montpellier school (Braun-Blanquet method, 1964). Biological attributes (Landolt et al., 2010) are assigned to phytocoenological relevé in which the processes of four types of biological behavior were analyzed: dispersal of diaspores (DA), vegetative dispersal (VA), flowering period (BZ) and pollination agents (BS). The phenology of invasive plant species was analyzed and compared with the phenology of other plants within the examined weed communities. The main aim of this research is to determine the basic differences between the phenology of invasive alien plants and weed species in the studied area. The results indicate that, when compared with other species of studied plant communities, the advantages of invasive plants are the following: dispersal by air currents over long distances, various ways of reproduction and higher intensity of flowering by the end of vegetation season. -

Ailanthus Altissima

Bulletin OEPP/EPPO Bulletin (2020) 50 (1), 148–155 ISSN 0250-8052. DOI: 10.1111/epp.12621 European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization Organisation Europe´enne et Me´diterrane´enne pour la Protection des Plantes PM 9/29 (1) National Regulatory Control Systems PM 9/29 (1) Ailanthus altissima Specific scope Specific approval and amendment This Standard describes the control procedures aiming to First approved in 2019–09. monitor, contain and eradicate Ailanthus altissima. species has been widely planted for ornamental and many 1. Introduction other uses (e.g. forestry and erosion control; Kowarik & Further information on the biology, distribution and eco- S€aumel, 2007) throughout the region and has become inva- nomic importance of Ailanthus altissima can be found in sive in many countries with the exception of the Nordic EPPO (2018) and CABI (2018). countries and Russia (EPPO, 2018). Ailanthus altissima can Ailanthus altissima (Mill.) Swingle (Simaroubaceae) is a have negative impacts on native biodiversity through direct broadleaved perennial early successional tree that is native competition and through allelopathic effects (Kowarik & to Asia (China and Vietnam). The species can grow up to S€aumel, 2007). The species can have negative impacts on 30 m in height and has alternately arranged compound ecosystem services as well as negative economic impacts leaves (Kowarik & S€aumel, 2007). The species is mainly by affecting infrastructure (Kowarik & S€aumel, 2007; Con- dioecious (male and female flowers occurring on different stan-Nava et al., 2014). The species can have human health trees). In the EPPO region flowering generally occurs dur- implications as contact with the leaves can cause severe ing July and August (Holec et al., 2014). -

Brisbane Native Plants by Suburb

INDEX - BRISBANE SUBURBS SPECIES LIST Acacia Ridge. ...........15 Chelmer ...................14 Hamilton. .................10 Mayne. .................25 Pullenvale............... 22 Toowong ....................46 Albion .......................25 Chermside West .11 Hawthorne................. 7 McDowall. ..............6 Torwood .....................47 Alderley ....................45 Clayfield ..................14 Heathwood.... 34. Meeandah.............. 2 Queensport ............32 Trinder Park ...............32 Algester.................... 15 Coopers Plains........32 Hemmant. .................32 Merthyr .................7 Annerley ...................32 Coorparoo ................3 Hendra. .................10 Middle Park .........19 Rainworth. ..............47 Underwood. ................41 Anstead ....................17 Corinda. ..................14 Herston ....................5 Milton ...................46 Ransome. ................32 Upper Brookfield .......23 Archerfield ...............32 Highgate Hill. ........43 Mitchelton ...........45 Red Hill.................... 43 Upper Mt gravatt. .......15 Ascot. .......................36 Darra .......................33 Hill End ..................45 Moggill. .................20 Richlands ................34 Ashgrove. ................26 Deagon ....................2 Holland Park........... 3 Moorooka. ............32 River Hills................ 19 Virginia ........................31 Aspley ......................31 Doboy ......................2 Morningside. .........3 Robertson ................42 Auchenflower -

Moths of Ohio Guide

MOTHS OF OHIO field guide DIVISION OF WILDLIFE This booklet is produced by the ODNR Division of Wildlife as a free publication. This booklet is not for resale. Any unauthorized INTRODUCTION reproduction is prohibited. All images within this booklet are copyrighted by the Division of Wildlife and it’s contributing artists and photographers. For additional information, please call 1-800-WILDLIFE. Text by: David J. Horn Ph.D Moths are one of the most diverse and plentiful HOW TO USE THIS GUIDE groups of insects in Ohio, and the world. An es- Scientific Name timated 160,000 species have thus far been cata- Common Name Group and Family Description: Featured Species logued worldwide, and about 13,000 species have Secondary images 1 Primary Image been found in North America north of Mexico. Secondary images 2 Occurrence We do not yet have a clear picture of the total Size: when at rest number of moth species in Ohio, as new species Visual Index Ohio Distribution are still added annually, but the number of species Current Page Description: Habitat & Host Plant is certainly over 3,000. Although not as popular Credit & Copyright as butterflies, moths are far more numerous than their better known kin. There is at least twenty Compared to many groups of animals, our knowledge of moth distribution is very times the number of species of moths in Ohio as incomplete. Many areas of the state have not been thoroughly surveyed and in some there are butterflies. counties hardly any species have been documented. Accordingly, the distribution maps in this booklet have three levels of shading: 1. -

Samia Cynthia in New Jersey Book Review, Market- Place, Metamorphosis, Announcements, Membership Updates

________________________________________________________________________________________ Volume 61, Number 4 Winter 2019 www.lepsoc.org ________________________________________________________________________________________ Inside: Butterflies of Papua Southern Pearly Eyes in exotic Louisiana venue Philippine butterflies and moths: a new website The Lepidopterists’ Society collecting statement updated Lep Soc, Southern Lep Soc, and Assoc of Trop Lep combined meeting Butterfly vicariance in southeast Asia Samia cynthia in New Jersey Book Review, Market- place, Metamorphosis, Announcements, Membership Updates ... and more! ________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________ Contents www.lepsoc.org ________________________________________________________ Digital Collecting -- Butterflies of Papua, Indonesia ____________________________________ Bill Berthet. .......................................................................................... 159 Volume 61, Number 4 Butterfly vicariance in Southeast Asia Winter 2019 John Grehan. ........................................................................................ 168 Metamorphosis. ....................................................................................... 171 The Lepidopterists’ Society is a non-profit ed- Membership Updates. ucational and scientific organization. The ob- Chris Grinter. ....................................................................................... 171 -

Plant Invasion As an Emerging Challenge for the Conservation of Heritage Sites: the Spread of Ornamental Trees on Ancient Monuments in Rome, Italy

Biol Invasions (2021) 23:1191–1206 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-020-02429-9 (0123456789().,-volV)( 0123456789().,-volV) ORIGINAL PAPER Plant invasion as an emerging challenge for the conservation of heritage sites: the spread of ornamental trees on ancient monuments in Rome, Italy Laura Celesti-Grapow . Carlo Ricotta Received: 30 June 2020 / Accepted: 23 November 2020 / Published online: 5 December 2020 Ó The Author(s) 2020 Abstract Cultural heritage sites such as historical or included among the invasive species of European sacred areas provide suitable habitats for plants and Union concern (EU Regulation 2019/1262). Our play an important role in nature conservation, partic- findings show that plant invasion is an emerging ularly in human-modified contexts such as urban challenge for the conservation of heritage sites and environments. However, such sites also provide needs to be prioritized for management to prevent opportunities for the spread of invasive species, whose future expansion. impact on monuments has been raising growing concerns. The aim of this study was to investigate Keywords Ailanthus altissima Á Biodeterioration Á the patterns of distribution and spread of invasive EU regulation on invasive alien species Á Impacts Á plants in heritage areas, taking the city of Rome as an Ornamental horticulture Á Urban flora example. We focused on woody species as they pose the greatest threat to the conservation of monuments, owing to the detrimental effects of their root system. We analysed changes in the diversity and traits of Introduction native and non-native flora growing on the walls of 26 ancient sites that have been surveyed repeatedly since Culturally protected sites, such as monumental or the 1940s. -

Assessing Potential Biological Control of the Invasive Plant, Tree-Of-Heaven, Ailanthus Altissima

This article was downloaded by: [USDA National Agricultural Library] On: 11 August 2009 Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 741288003] Publisher Taylor & Francis Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Biocontrol Science and Technology Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713409232 Assessing potential biological control of the invasive plant, tree-of-heaven, Ailanthus altissima Jianqing Ding a; Yun Wu b; Hao Zheng a; Weidong Fu a; Richard Reardon b; Min Liu a a Institute of Biological Control, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Beijing, P.R. China b Forest Health Technology Enterprise Team, USDA Forest Service, Morgantown, USA Online Publication Date: 01 June 2006 To cite this Article Ding, Jianqing, Wu, Yun, Zheng, Hao, Fu, Weidong, Reardon, Richard and Liu, Min(2006)'Assessing potential biological control of the invasive plant, tree-of-heaven, Ailanthus altissima',Biocontrol Science and Technology,16:6,547 — 566 To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/09583150500531909 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09583150500531909 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. -

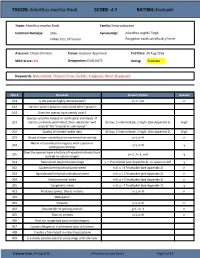

TAXON:Ailanthus Excelsa Roxb. SCORE:4.0 RATING:Evaluate

TAXON: Ailanthus excelsa Roxb. SCORE: 4.0 RATING: Evaluate Taxon: Ailanthus excelsa Roxb. Family: Simaroubaceae Common Name(s): ardu Synonym(s): Ailanthus wightii Tiegh. Indian tree of heaven Pongelion excelsum (Roxb.) Pierre Assessor: Chuck Chimera Status: Assessor Approved End Date: 24 Aug 2016 WRA Score: 4.0 Designation: EVALUATE Rating: Evaluate Keywords: Naturalized, Tropical Tree, Fodder, Coppices, Wind-Dispersed Qsn # Question Answer Option Answer 101 Is the species highly domesticated? y=-3, n=0 n 102 Has the species become naturalized where grown? 103 Does the species have weedy races? Species suited to tropical or subtropical climate(s) - If 201 island is primarily wet habitat, then substitute "wet (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2-high) (See Appendix 2) High tropical" for "tropical or subtropical" 202 Quality of climate match data (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2-high) (See Appendix 2) High 203 Broad climate suitability (environmental versatility) y=1, n=0 n Native or naturalized in regions with tropical or 204 y=1, n=0 y subtropical climates Does the species have a history of repeated introductions 205 y=-2, ?=-1, n=0 y outside its natural range? 301 Naturalized beyond native range y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2), n= question 205 y 302 Garden/amenity/disturbance weed n=0, y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2) n 303 Agricultural/forestry/horticultural weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see Appendix 2) n 304 Environmental weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see Appendix 2) n 305 Congeneric weed n=0, y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2) y 401 Produces spines, thorns or burrs y=1, n=0 n 402 Allelopathic 403 Parasitic y=1, n=0 n 404 Unpalatable to grazing animals y=1, n=-1 n 405 Toxic to animals y=1, n=0 n 406 Host for recognized pests and pathogens 407 Causes allergies or is otherwise toxic to humans 408 Creates a fire hazard in natural ecosystems 409 Is a shade tolerant plant at some stage of its life cycle Creation Date: 24 Aug 2016 (Ailanthus excelsa Roxb.) Page 1 of 17 TAXON: Ailanthus excelsa Roxb.