The Story of the Begin Highway in Beit Safafa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jerusalem Chronology 2015 January Jan. 1: the Israeli Supreme Court

Jerusalem Chronology 2015 January Jan. 1: The Israeli Supreme Court rejects an appeal to prevent the demolition of the homes of four Palestinians from East Jerusalem who attacked Israelis in West Jerusalem in recent months. - Marabouts at Al-Aqsa Mosque confront a group of settlers touring Al-Aqsa compound. Jan. 3: Palestinian MK Ahmad Tibi joins hundreds of Palestinians marching toward the Al-Aqsa Mosque in the Old City of Jerusalem to mark the Prophet Muhammad's birthday. Jan. 5: Settlers tour Al-Aqsa Mosque compound while Israeli forces confiscate the IDs of Muslims trying to enter. - Around 50 Israeli forces along with 18 settlers tour Al-Aqsa compound. Jan. 8: A Jewish Israeli man is stabbed and injured by an unknown assailant while walking near the Old City’s Damascus Gate. Jan. 9: Israeli police detain at least seven Palestinians in a series of raids in the Old City over the stabbing a day earlier. - Yedioth Ahronoth reports that the Israeli Intelligence (Shabak) frustrated an operation that was intended to blow the Dome of the Rock by an American immigrant. Jan. 11: Israeli police forces detain seven Palestinians from Silwan after a settler vehicle was torched in the area. Jan. 12: A Jerusalem magistrate court has ruled that Israeli settlers who occupied Palestinian homes in East Jerusalem may not make substantial changes to the properties. - Settlers tour Al-Aqsa Mosque compound. Jan. 13: Israeli forces detained three 14-year old youth during a raid on Issawiyya and two women while leaving Al-Aqsa Mosque. Jan. 14: Jewish extremists morning punctured the tires of 11 vehicles in Beit Safafa. -

4.Employment Education Hebrew Arnona Culture and Leisure

Did you know? Jerusalem has... STARTUPS OVER OPERATING IN THE CITY OVER SITES AND 500 SYNAGOGUES 1200 39 MUSEUMS ALTITUDE OF 630M CULTURAL INSTITUTIONS COMMUNITY 51 AND ARTS CENTERS 27 MANAGERS ( ) Aliyah2Jerusalem ( ) Aliyah2Jerusalem JERUSALEM IS ISRAEL’S STUDENTS LARGEST CITY 126,000 DUNAM Graphic design by OVER 40,000 STUDYING IN THE CITY 50,000 VOLUNTEERS Illustration by www.rinatgilboa.com • Learning centers are available throughout the city at the local Provide assistance for olim to help facilitate a smooth absorption facilities. The centers offer enrichment and study and successful integration into Jerusalem. programs for school age children. • Jerusalem offers a large selection of public and private schools Pre - Aliyah Services 2 within a broad religious spectrum. Also available are a broad range of learning methods offered by specialized schools. Assistance in registration for municipal educational frameworks. Special in Jerusalem! Assistance in finding residence, and organizing community needs. • Tuition subsidies for Olim who come to study in higher education and 16 Community Absorption Coordinators fit certain criteria. Work as a part of the community administrations throughout the • Jerusalem is home to more than 30 institutions of higher education city; these coordinators offer services in educational, cultural, sports, that are recognized by the Student Authority of the Ministry of administrative and social needs for Olim at the various community Immigration & Absorption. Among these schools is Hebrew University – centers. -

General Plan for East Jerusalem: the State of Public Spaces and Future Needs

General Plan for East Jerusalem: the state of public spaces and future needs (DRAFT) International Peace and Cooperation Center (IPCC) UNDP CRDP project February 2016 East Jerusalem General Plan International Peace and Cooperation Center East Jerusalem General Plan International Peace and Cooperation Center List of Appendices Appendix A Population Data ........................................................................................................... A-1 Appendix B Education Additional Information .............................................................................. B-1 Appendix C Health Additional Information .................................................................................... C-1 Appendix D Open Spaces Additional Information .......................................................................... D-1 Appendix E Community/Cultural Additional Information ............................................................. E-1 Appendix F IPCC Existing Work Additional Information ............................................................. F-1 Appendix G Schedule of Existing Public Facilities......................................................................... G-1 Appendix H Schedule of Potential Land for Development ............................................................. H-1 Appendix I Priority Projects............................................................................................................ I-1 List of Figures Figure 1 East Jerusalem Neighbourhoods and Zones ......................................................................... -

Greater Jerusalem” Has Jerusalem (Including the 1967 Rehavia Occupied and Annexed East Jerusalem) As Its Centre

4 B?63 B?466 ! np ! 4 B?43 m D"D" np Migron Beituniya B?457 Modi'in Bei!r Im'in Beit Sira IsraelRei'ut-proclaimed “GKharbrathae al Miasbah ter JerusaBeitl 'Uer al Famuqa ” D" Kochav Ya'akov West 'Ein as Sultan Mitzpe Danny Maccabim D" Kochav Ya'akov np Ma'ale Mikhmas A System of Settler-Colonialism and Apartheid Deir Quruntul Kochav Ya'akov East ! Kafr 'Aqab Kh. Bwerah Mikhmas ! Beit Horon Duyuk at Tahta B?443 'Ein ad D" Rafat Jericho 'Ajanjul ya At Tira np ya ! Beit Liq Qalandi Kochav Ya'akov South ! Lebanon Neve Erez ¥ ! Qalandiya Giv'at Ze'ev D" a i r Jaba' y 60 Beit Duqqu Al Judeira 60 B? a S Beit Nuba D" B? e Atarot Ind. Zone S Ar Ram Ma'ale Hagit Bir Nabala Geva Binyamin n Al Jib a Beit Nuba Beit 'Anan e ! Giv'on Hahadasha n a r Mevo Horon r Beit Ijza e t B?4 i 3 Dahiyat al Bareed np 6 Jaber d Aqbat e Neve Ya'akov 4 M Yalu B?2 Nitaf 4 !< ! ! Kharayib Umm al Lahim Qatanna Hizma Al Qubeiba ! An Nabi Samwil Ein Prat Biddu el Almon Har Shmu !< Beit Hanina al Balad Kfar Adummim ! Beit Hanina D" 436 Vered Jericho Nataf B? 20 B? gat Ze'ev D" Dayr! Ayyub Pis A 4 1 Tra Beit Surik B?37 !< in Beit Tuul dar ! Har A JLR Beit Iksa Mizpe Jericho !< kfar Adummim !< 21 Ma'ale HaHamisha B? 'Anata !< !< Jordan Shu'fat !< !< A1 Train Ramat Shlomo np Ramot Allon D" Shu'fat !< !< Neve Ilan E1 !< Egypt Abu Ghosh !< B?1 French Hill Mishor Adumim ! B?1 Beit Naqquba !< !< !< ! Beit Nekofa Mevaseret Zion Ramat Eshkol 1 Israeli Police HQ Mesilat Zion B? Al 'Isawiya Lifta a Qulunyia ! Ma'alot Dafna Sho'eva ! !< Motza Sheikh Jarrah !< Motza Illit Mishor Adummim Ind. -

Jerusalem: Facts and Trends 2009 / 2010

Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies Founded by the Charles H. Revson Foundation Jerusalem: Facts and Trends 2009 / 2010 Maya Choshen, Michal Korach 2010 Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies Publication No. 402 Jerusalem: Facts and Trends 2009/2010 Maya Choshen, Michal Korach This publication was published with the assistance of the Charles H. Revson Foundation, New York The authors alone are responsible for the contents of the publication Translation from Hebrew: Sagir International Translation, Ltd. © 2010, Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies The Hay Elyachar House 20 Radak St., 92186 Jerusalem [email protected] http://www.jiis.org Table of Contents About the Authors ............................................................................................. 7 Preface ................................................................................................................ 8 Area .................................................................................................................... 9 Population ......................................................................................................... 9 Population size ........................................................................................... 9 Geographical distribution of the population .............................................11 Population growth .................................................................................... 12 Sources of population growth .................................................................. 12 Birth -

O Occupied East Jerusalem

Occupied East Jerusalem “De-Palestinization” and Forcible Transfer of Palestinians A situation of systematic breaches of State obligations under the ICCPR JOINT NGO REPORT to the UN Human Rights Committee For the Committee’s Review of the Fourth Periodic Report of ISRAEL Submitted by: The Civic Coalition for Palestinian Rights in Jerusalem (CCPRJ) Contact: Zakaria Odeh, executive director Email: [email protected] Tel: +972 2 2343929 www.civiccoalition-jerusalem.org The Coalition for Jerusalem (CFJ) Contact: Aminah Abdelhaq, coordinator Email: [email protected] Tel: +972 2 6562272 url: www.coalitionforjerusalem.org The Society of St. Yves, Catholic Center for Human Rights (St. Yves) Contact: Dalia Qumsieh, head of advocacy Email: [email protected] Tel: +972 2 6264662 url: www.saintyves.org 1 Content Introduction Paragraph RECOMMENDATIONS A. Constitutional and legal framework within which the Covenant is implemented by Israel in occupied East Jerusalem (Art. 1, 2) Question 4: Application of the Covenant in the Occupied Palestinian Territory (OPT) 4 – 11 Question 5: Equality and non-discrimination in Israeli law, courts; other measures 12 – 22 Recommended Questions to the State party (Art. 1 and 2) B. State of Emergency (Art. 4); derogations from international standards Questions 12, 19: Progress in review of Israel’s state of emergency; derogations 23 – 25 from international standards (complementary issues) Recommended Questions to State party (Article 4) C. Freedom of movement and residence (Art. 12, 2; also 14, 17, 23, 24, 26) Questions 20, 21: Complementary information on Palestinians in East Jerusalem 26 – 34 D. Protection of the Family, Protection of the Child (Art.23, 24, 2; 12, 14, 17, 24, 26) Question 25: Measures taken by the State party to revoke the Citizenship and 35 – 45 Entry Into Israel Law; right to marriage E. -

Gaza Strip West Bank

Afula MAP 3: Land Swap Option 3 Zububa Umm Rummana Al-Fahm Mt. Gilboa Land Swap: Israeli to Palestinian At-Tayba Silat Al-Harithiya Al Jalama Anin Arrana Beit Shean Land Swap: Palestinian to Israeli Faqqu’a Al-Yamun Umm Hinanit Kafr Dan Israeli settlements Shaked Al-Qutuf Barta’a Rechan Al-Araqa Ash-Sharqiya Jenin Jalbun Deir Abu Da’if Palestinian communities Birqin 6 Ya’bad Kufeirit East Jerusalem Qaffin Al-Mughayyir A Chermesh Mevo No Man’s Land Nazlat Isa Dotan Qabatiya Baqa Arraba Ash-Sharqiya 1967 Green Line Raba Misiliya Az-Zababida Zeita Seida Fahma Kafr Ra’i Illar Mechola Barrier completed Attil Ajja Sanur Aqqaba Shadmot Barrier under construction B Deir Meithalun Mechola Al-Ghusun Tayasir Al-Judeida Bal’a Siris Israeli tunnel/Palestinian Jaba Tubas Nur Shams Silat overland route Camp Adh-Dhahr Al-Fandaqumiya Dhinnaba Anabta Bizzariya Tulkarem Burqa El-Far’a Kafr Yasid Camp Highway al-Labad Beit Imrin Far’un Avne Enav Ramin Wadi Al-Far’a Tammun Chefetz Primary road Sabastiya Talluza Beit Lid Shavei Shomron Al-Badhan Tayibe Asira Chemdat Deir Sharaf Roi Sources: See copyright page. Ash-Shamaliya Bekaot Salit Beit Iba Elon Moreh Tire Ein Beit El-Ma Azmut Kafr Camp Kafr Qaddum Deir Al-Hatab Jammal Kedumim Nablus Jit Sarra Askar Salim Camp Chamra Hajja Tell Balata Tzufim Jayyus Bracha Camp Beit Dajan Immatin Kafr Qallil Rujeib 2 Burin Qalqiliya Jinsafut Asira Al Qibliya Beit Furik Argaman Alfe Azzun Karne Shomron Yitzhar Itamar Mechora Menashe Awarta Habla Maale Shomron Immanuel Urif Al-Jiftlik Nofim Kafr Thulth Huwwara 3 Yakir Einabus -

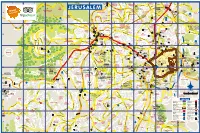

Jerusalem-Map.Pdf

H B S A H H A R ARAN H A E K A O RAMOT S K R SQ. G H 1 H A Q T V V HI TEC D A E N BEN G GOLDA MEIR I U V TO E R T A N U H M HA’ADMOR ESHKOL E 1 2 3 R 4 5 Y 6 DI ZAHA 7 MA H 8 E Z K A 9 INTCH. T A A MEGUR A E AR I INDUSTRY M SANHEDRIYYA GIV’AT Z L LOH T O O T ’A N Y A O H E PARA A M R N R T E A O 9 R (HAR HOZVIM) A Y V M EZEL H A A AM M AR HAMITLE A R D A A MURHEVET SUF I HAMIVTAR A G P N M A H M ET T O V E MISHMAR HAGEVUL G A’O A A N . D 1 O F A (SHAPIRA) H E ’ O IRA S T A A R A I S . D P A P A M AVE. Lev LEHI D KOL 417 i E V G O SH sh E k Y HAR O R VI ol L O I Sanhedrin E Tu DA M L AMMUNITION n n N M e E’IR L Tombs & Garden HILL l AV 436 E REFIDIM TAMIR JERUSALEM E. H I EZRAT T N K O EZRAT E E AV S M VE. R ORO R R L HAR HAMENUHOT A A A T E N A Z ’ Ammunition I H KI QIRYAT N M G TORA O 60 British Military (JEWISH CEMETERY) E HASANHEDRIN A N Hill H M I B I H A ZANS IV’AT MOSH H SANHEDRIYYA Cemetery QIRYAT SHEVA E L A M D Y G U TO MEV U S ’ L C E O Y M A H N H QIRYAT A IKH E . -

Imagining the Border

A WAshington institute str Ategic r eport Imagining the Border Options for Resolving the Israeli-Palestinian Territorial Issue z David Makovsky with Sheli Chabon and Jennifer Logan A WAshington institute str Ategic r eport Imagining the Border Options for Resolving the Israeli-Palestinian Territorial Issue z David Makovsky with Sheli Chabon and Jennifer Logan All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. © 2011 The Washington Institute for Near East Policy Published in 2011 in the United States of America by the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, 1828 L Street NW, Suite 1050, Washington, DC 20036. Design by Daniel Kohan, Sensical Design and Communication Front cover: President Barack Obama watches as Israeli prime minister Binyamin Netanyahu and Palestinian president Mahmoud Abbas shake hands in New York, September 2009. (AP Photo/Charles Dharapak) Map CREDITS Israeli settlements in the Triangle Area and the West Bank: Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics, 2007, 2008, and 2009 data Palestinian communities in the West Bank: Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, 2007 data Jerusalem neighborhoods: Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies, 2008 data Various map elements (Green Line, No Man’s Land, Old City, Jerusalem municipal bounds, fences, roads): Dan Rothem, S. Daniel Abraham Center for Middle East Peace Cartography: International Mapping Associates, Ellicott City, MD Contents About the Authors / v Acknowledgments / vii Settlements and Swaps: Envisioning an Israeli-Palestinian Border / 1 Three Land Swap Scenarios / 7 Maps 1. -

East Jerusalem

?B463 Kafr Ni'ma Dolev Mu'arrajaat - caravan side Deir Ibzi' P! Al Bireh Deir Dibwan !P P! 'Ein 'Arik P! Qaddura DG !# Wadi As Seeq P! Camp T P! "J!P Khirbet kafr Sheiyhan Pesagot Burqa # Ramallah P! Khalet al Maghara P! P! 450 F G P! H I D " " " " " " " " " B D " " "" ?" " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " Beituniya " " " " " " "" " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " "" "" " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " "" " "" " " " " " " " " " " # " " " " " "" " " " " " " " " " " " " " " """ " " " " " " " " " " "" " " " " " " " " Beit 'Ur " " " " "" " " "" " " " "" " " " "" " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " "" " " " " " " "" " " " " Migron " " " " " " !P " " " " " """ " " " United" " "" " Nations" " " " Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs " " " " " "" " " " " " " "" " " " """ " " " " " " " " " " " " " "" "" "" Beituniya " " " " " " "" " " " "" " " " " " " " " " "" " " " " " " " " Maghayer Al Dir " " " " 457 " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " GF al Fauqa " " " " " " " "" " " " "" " " " " " "" " " " "" " " " " " " ! " B P " " " " "" " ? " " " " " " " "" " " " "" " " " " "" " " " " " " " " " "" "" " " " " " " " "" " " "" " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " "" " " "" " " " " " "" WEST" " BANK ACCESS " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " "" "" "" " " " " "" " """" " " " " " " "" """" " " "" " "" " " " " " " " " "" " " " " " """ " " " " "" " " " " "" " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " "" "" " " " " "" " " " """ " " " " " " " " " " " "" " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " "" "" " "" " " " " " " " " " RESTRICTIONS -

Economic Consequences

Shir Hever The Economy of the Occupation A Socioeconomic Bulletin The Separation Wall in East Jerusalem Economic Consequences № 11-12 * January-February 2007 Shir Hever Economy of the Occupation ___________________________________________Socioeconomic Bulletin № 10-12 The Separation Wall in East Jerusalem ___________________________________________Economic Consequences January-February 2007 Published by the Alternative Information Center (AIC) http://www.alternativenews.org/ Jerusalem Beit Sahour 4 Queen Shlomzion Street Building 111 Main Street PO Box 31417 PO Box 201 Jerusalem, Israel 91313 Beit Sahour, Palestine Phone: 972-(0)2-624-1159; 624-1424 Phone: 972-(0)2-277-5444 Fax: 972-(0)2-625-3151 Fax: 972-(0)2-277-5445 Graphic Designer: Tal Hever Printer: Latin Patriarchate Printing Press Photograph on the Cover: Niv Hachlili, September 2004 The AIC wishes to acknowledge the generous support for its activities by: Associazione Comunita Papa Giovanni XXIII, Broederlijk Delen, the Catalan Government through the help of Sodepau, Comite Catholique Contre La Faim Et Pour Le Developemment (CCFD), Diakonia, Inter-Church Organisation for Development Cooperation (ICCO), the Irish Government through the help Christian Aid, Junta Castilla-La Mancha through the help of ACSUR Las Segovias. Table of Contents: ___________________________________________ 1.) Introduction 4 2.) The Situation in East Jerusalem before the Wall 5 3.) The Wall 8 4.) The Recent Shifts in the Labor Movements in Israel and the OPT 10 5.) Labor Movements in Jerusalem and the Quality of Life 12 6.) The Seeds of Discontent 15 7.) Conclusion 19 25 Bibliography 30 ___________________________________________ Special thanks to Rami Adut for his many contributions to this research from its very beginning and especially for his help in compiling the data for the study, for Yael Berda for sharing her expertise and for OCHA for allowing the use of their maps. -

2.6 Ash-Sheikh Jarrah About the Neighborhood Ventured out of the Fortified Old City

2.6 Ash-Sheikh Jarrah About the Neighborhood ventured out of the fortified Old City. Jews and Arabs settled around the small historical village called Jarrah Ash-Sheikh Jarrah, part of the East Jerusalem city (surgeon, in Arabic), named after Salah ad-Din’s doctor, center, is bordered by the pre-1967 Israeli neighborhood to whom the parcel of land was granted as a sign Survey of Palestinian Neighborhoods in East Jerusalem of Shmuel Hanavi, to the southwest, and by three of appreciation following the Muslim conquest of Jerusalem Center Israeli neighborhoods that were built beyond the Jerusalem. Homes and estates, built by the Palestinian Green Line after 1967: Givat Shapira (aka French Hill) aristocracy (Husseini, Nashashibi, Khalidi) during the and Ramot Eshkol to the north, and Ma’alot Dafna to first half of the 20th century, serve today as tourist the west. Between 1949 and 1967, ash-Sheikh Jarrah sites, cultural centers, and foreign consulates. These was included within the municipal boundary of the structures are an important symbol of Palestinian- Jordanian city, and the “no man’s land” buffer zone Jerusalemite identity. was the de-facto western border of the neighborhood. Ash-Sheikh Jarrah has been in the headlines in recent Today, the neighborhood is mostly located to the east years due to the vocal struggle of the Solidarity • of Haim Bar Lev Boulevard (known as Road 1) and movement against aggressive Jewish-Israeli settlement City Center Zone can be divided into two distinctive socio-economic activity in the heart of the neighborhood. The aim of the sections.