THE Official Magazine of the OCEANOGRAPHY SOCIETY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report Resumes

REPORT RESUMES ED 019 218 88 SE 004 494 A RESOURCE BOOK OF AEROSPACE ACTIVITIES, K-6. LINCOLN PUBLIC SCHOOLS, NEBR. PUB DATE 67 EDRS PRICEMF.41.00 HC-S10.48 260P. DESCRIPTORS- *ELEMENTARY SCHOOL SCIENCE, *PHYSICAL SCIENCES, *TEACHING GUIDES, *SECONDARY SCHOOL SCIENCE, *SCIENCE ACTIVITIES, ASTRONOMY, BIOGRAPHIES, BIBLIOGRAPHIES, FILMS, FILMSTRIPS, FIELD TRIPS, SCIENCE HISTORY, VOCABULARY, THIS RESOURCE BOOK OF ACTIVITIES WAS WRITTEN FOR TEACHERS OF GRADES K-6, TO HELP THEM INTEGRATE AEROSPACE SCIENCE WITH THE REGULAR LEARNING EXPERIENCES OF THE CLASSROOM. SUGGESTIONS ARE MADE FOR INTRODUCING AEROSPACE CONCEPTS INTO THE VARIOUS SUBJECT FIELDS SUCH AS LANGUAGE ARTS, MATHEMATICS, PHYSICAL EDUCATION, SOCIAL STUDIES, AND OTHERS. SUBJECT CATEGORIES ARE (1) DEVELOPMENT OF FLIGHT, (2) PIONEERS OF THE AIR (BIOGRAPHY),(3) ARTIFICIAL SATELLITES AND SPACE PROBES,(4) MANNED SPACE FLIGHT,(5) THE VASTNESS OF SPACE, AND (6) FUTURE SPACE VENTURES. SUGGESTIONS ARE MADE THROUGHOUT FOR USING THE MATERIAL AND THEMES FOR DEVELOPING INTEREST IN THE REGULAR LEARNING EXPERIENCES BY INVOLVING STUDENTS IN AEROSPACE ACTIVITIES. INCLUDED ARE LISTS OF SOURCES OF INFORMATION SUCH AS (1) BOOKS,(2) PAMPHLETS, (3) FILMS,(4) FILMSTRIPS,(5) MAGAZINE ARTICLES,(6) CHARTS, AND (7) MODELS. GRADE LEVEL APPROPRIATENESS OF THESE MATERIALSIS INDICATED. (DH) 4:14.1,-) 1783 1490 ,r- 6e tt*.___.Vhf 1842 1869 LINCOLN PUBLICSCHOOLS A RESOURCEBOOK OF AEROSPACEACTIVITIES U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION K-6) THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRODUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIGINATING IT.POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OF EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY. 1919 O O Vj A PROJECT FUNDED UNDER TITLE HIELEMENTARY AND SECONDARY EDUCATION ACT A RESOURCE BOOK OF AEROSPACE ACTIVITIES (K-6) The work presentedor reported herein was performed pursuant to a Grant from the U. -

Volatiles in the Moon: a Sulfur and Chlorine Perspective

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Volatiles in the Moon: A sulfur and chlorine perspective Thesis How to cite: Faircloth, Samantha Jane (2020). Volatiles in the Moon: A sulfur and chlorine perspective. PhD thesis The Open University. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2020 The Author https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Version: Version of Record Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21954/ou.ro.00011603 Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk Volatiles in the Moon: A sulfur and chlorine perspective Samantha Jane Faircloth MSc, BSc (Hons), BA (Hons) This thesis was submitted to The Open University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Physical Sciences February 2020 ii Abstract Sulfur is a key volatile element in magmatic systems that exists in many phases (e.g. melt or gas), in multiple-oxidation states (S2-, S4+ and S6+), and has more than one stable isotope (e.g. 32S and 34S). Therefore, by measuring S, information regarding the conditions of a magma can be acquired. The aim of this work is to investigate what S can tell us about the behaviour of late-stage lunar basaltic magmas. An analytical protocol was developed to simultaneously measure S and Cl abundances and isotopes of lunar apatite in eleven lunar basalts with nano-scale secondary ion mass spectrometry (NanoSIMS). -

(1) a Directory to Sources Of

DOCUMENT' RESUME ED 027 211 SE006 281 By-McIntyre, Kenneth M. Space ScienCe Educational Media Resources, A Guide for Junior High SchoolTeachers. NatiOnal Aeronautics and Space Administration, Washington, D.C. Pub Date Jun 66 Note-108p. Available from-National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Washington, D.C.($3.50) EDRS Price MF -$0.50 HC Not Available from EDRS. Descriptors-*Aerospace Technology, Earth Science, Films, Filmstrips, Grade 8,*Instructional Media, *Resource Guides, *Science Activities, *Secondary School Science, Teaching Guides,Transparencies Identifiers-National Aeronautics and Space AdMinistration This guide, developed bya panel of teacher consultants, is a correlation of educational mediaresources with the "North Carolina Curricular Bulletin for Eighth Grade Earth and Space Science" and thestate adopted textbook, pModern Earth Science." The three maior divisionsare (1) the Earth in Space (Astronomy), (2) Space Exploration, and (3) Meterology. Included. for theprimary topics under each division are (1) statements of concepts, (2) student activities, and (3) annotated listings of films, filmstrips, film-loops, transparencies, slides,and other forms of instructional media. Appendixesare (1) a directory to sources of instructional media, (2) a title index to the films and filmstrips cited, (3)a listing of bibliographies, guides, and printed materials related to aerospace edUcation. (RS) DOCUMENT. RESUM.E. ED 027 211 SE 006 281 By-McIntyre, Kenneth M. Space ScienCe Educational Media Resources, A Guide for JuniorHigh School Teachers. National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Washington, D.C. Pub Date Jun 66 Note-108p. Available from-National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Washington, D.C.($3.50) EDRS Price MF -$0.50 HC Not Available from EDRS. -

Bert Megquier, Wes Strasser Open New Store Her

' <» *t< - . i • .K» '» W Z Montana StateHistorical Library (comp' «(STORICA^ SO0IÊ1-» OF MONTANA ^ HfiifNA BERT MEGQUIER, Floyd Vandegrift Hurt In Accident WES STRASSER Floyd Vandegrift is confined to his home with injuries as the re OPEN NEW STORE sult of an automobile accident which occurred Saturday.. He was Largest Paid Circulation oi Any Newspaper in Beaverhead County taking seven members of the Col legian basketball team to Butte VOLUME NO. 73 DILLON, MONTANA, TUESDAY, APRIL 6, 1954 No. 166 to play in a tournament when his car and a truck driven by Garth Taylor collided on highway 91 north of Bond spur. The other JUNIOR PLAY CARL DAVIS AND members of the team and Mr. Taylor were uninjured. TONIGHT AND jo h n McDo n ald Big Hole Parish WEDNESDAY FILE FOR OFFICE The junior class of Beaverhead Filing for county offices in the Meeting Wednesday County High School is presenting July 20 primary election Monday The Big Hole Parish Council the annual play this evening and were Carl Davis for re-election as I will meet Wednesday evening at Wednesday evening at the school county attorney on the Democratic 8 o’clock at the Fishtrap school, auditorium starting at 8:15. ticket and John B. McDonald for j Several important subjects will be The cast includes Charles Mur sheriff on the Democratic ticket. .discussed including Easter and ray, Mickey Magee, Mary Me- ! Mr. Davis resumed his duties as i Good Friday services, vacation Laughlin, Barbara King, George county attorney April 1, after re I Bible school plans and the reor Slanger, Donna Krause, Carolyn turning from a second hitch in the ganization of the Parish. -

Frogpond 38.1 • Winter 2015 (Pdf)

F rogpond T he Journal o F T he h aiku SocieT y o F a merica V olume 38:1 W inT er 2015 About HSA & Frogpond Subscription / HSA Membership: For adults in the USA, $35; in Canada/Mexico, $37; for seniors and students in North America, $30; for everyone elsewhere, $47. Pay by check on a USA bank, by International Postal Money Or- der, or PayPal. All subscriptions/memberships are annual, expiring on December 31, and include three issues of Frogpond as well as three online newsletters, the members’ anthology, and voting rights. All correspondence regarding new and renewed memberships, changes of address, and requests for information should be directed to the HSA secretary (see the list of offcers, p. 146). Make checks and money orders payable to Haiku Society of America, Inc. Single Copies of Back Issues: For USA & Canada, $14; for elsewhere, $15 by surface and $20 by airmail. Older issues might cost more, depending on how many are left. Please inquire frst. Make checks payable to Haiku Society of America, Inc. Send single copy and back issue orders to the Frogpond editor (see p. 3). Contributor Copyright and Acknowledgments: All prior copyrights are retained by contributors. Full rights revert to contributors upon publication in Frogpond. Neither the Haiku Society of America, its offcers, nor the editor assume responsibility for views of contributors (including its own offcers) whose work is printed in Frogpond, research errors, infringement of copyrights, or failure to make proper acknowledgments. Frogpond Listing and Copyright Information: ISSN 8755-156X Listed in the MLA International Bibliography, Humanities Interna- tional Complete, Poets and Writers. -

The CHARIOTEER an Annual Review of Modern Greek Culture

The CHARIOTEER An Annual Review of Modern Greek Culture NUMBERS 33/34 1991-1992 SPECIAL DOUBLE ISSUE NIKIFOROS VRETT AKOS , C. Capri-Karka and R. M. Newton Y UNDER THE ACROPOLIS Tral'M:l~tterl by C. Capri-Karka and I. Karka CHORUS Translated by M. Chambers SELECTIONS FROM: COLLECTED POEMS VOL. 1 \ COLLECTED POEMS VOL. 2 PROTEST SUN LAMP GIFT IN ABEYANCE ENCOUNTER WITH THE SEA Tunslated by A. Michopoulos, G. Pilit9is, D. Connolly R. M. Newton, M. Chambers, I. Karka and M. Polis INTERVIEWS WITH NIKIFOROS VRETTAKOS Translated by A. Michopoulos and M. C. Pantelia A SELECTION OF CRITICAL ESSAYS by A. Argyriou, S. Geranis, K. Haralambides T. Patrikios and Vinzenzo Rotolo T<ranslated by M. C. Pantelia, R. M. Newton A. Michopoulos and C. Capri-Karka $15.00 THE CHARIOTEER AN ANNUAL REVIEW OF MODERN GREEK CULTURE Formerly published by P ARNASSOS Greek Cultural Society of New York NUMBERS 33/34 1991-1992 Publisher: LEANDROS PAPATHANASIOU Editor: c. CAPRI-KARKA Managing Editor: SOPHIA A. PAPPAS THE CHARIOTEER is published by PELLA PUBLISHING COMPANY, INC. Editorial and subscription address: Pella Publishing Company, 337 West 36th Street, New York, NY 10018. One year subscription $15; Two-year subscription $28; Three-year subscription $40. Copyright 1992 by Pella Publishing Company, Inc. All rights reserved. Printed in U.S.A. by Athens Printing Co., 337 West 36th Street, New York, NY 10018-6401-The CHARIOTEER solicits essays on and English translations from works of modern Greek writers. Translations should be accompanied by a copy of the original Greek text. Manuscripts will not be returned unless accompanied by a stamped self-addressed envelope. -

The Moon at the Bottom of the Well Ebook

THE MOON AT THE BOTTOM OF THE WELL PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Justin Stares | 172 pages | 30 Jun 2010 | Revel Barker | 9780956368652 | English | Brighton, United Kingdom From The Bottom Of The Well | KHD Many describe this as when the 'horns' of the Moon point upward. This can happen once or twice a year, again depending on the latitude of your location. This change in the appearance of the Moon has been observed for a very long time. And many conflicting definitions have been given to these lunar appearances. Some ancient skywatchers spoke of the crescent Moon when the bottom seems to be lit as the "wet moon". They thought it looked like a bowl which could fill up with the rain and snow of the winter season. However, many other cultures have defined the Moon when lit on the bottom as the "dry moon" since in that configuration, the Moon is "holding in the water". As winter passes into spring and summer, the crescent shape slowly shifts toward the south and begins to "stand on its end". To some ancients, this represented the Moon assuming a pouring position in which it will lose its water and result in the great summer rains. The result was the creation of a "dry moon", one which held no water because it all poured out. On the other hand, other cultures said that such a moon is a wet moon because it allowed the water to pour out! Expand the sub menu TV. Expand the sub menu What To Watch. Expand the sub menu Music. -

Els2016.Arc.Nasa.Gov

els2016.arc.nasa.gov Wim van Westrenen, VU University, Amsterdam, NL (Chair) Mahesh Anand, Open University, UK (Co-Chair) Jessica Barnes, Open University, UK Maxim Litvak, RAS, Russia James Carpenter, ESA Patrick Pinet, IRAP, France Doris Daou, NASA, USA Katie Robinson, Open University, UK Simone Dell’Agnello, INFN, Italy Greg Schmidt, SSERVI, USA Ralf Jaumann, DLR, Germany 1 Updated: 5th May 2016 (v. 1.8) Program for ELS 2016, the Fourth European Lunar Symposium http://els2016.arc.nasa.gov/ Venue Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences (KNAW) The Trippenhuis Kloveniersburgwal 29 1011 JV Amsterdam, the Netherlands Science Organizing Committee • Wim van Westrenen - VU Univ. Amsterdam, NL (Chair) • Mahesh Anand - Open University, UK (Co-Chair) • Jessica Barnes - Open University, UK • James Carpenter - ESA • Doris Daou - NASA, PSD • Simone Dell'Agnello - INFN, Italy • Ralf Jaumann - DLR, Germany • Maxim Litvak - Space Research Institute, RAS, Moscow • Patrick Pinet - IRAP, France • Katharine Robinson - Open University, UK • Greg Schmidt - SSERVI, USA Tuesday 17th May 2016 ELS 2016 Onsite Registration 18:00 - 19:00 Registration (Tea/Coffee/refreshments) 19:00 – 20:00 Inaugural lecture (Prof. Harry Hiesinger, University of Muenster and Prof. Mark Robinson, University of Arizona) – Seven Years Exploring the Moon: Highlights from Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) Mission; Chair – Prof. Ralf Jaumann 20:00 – 21:00 Welcome Reception with drinks and snacks Note: Names in bold are invited speakers. 2 Updated: 5th May 2016 (v. 1.8) Wednesday 18th May 2016 08:15 Registration (Tea/Coffee/Refreshments) 08:45 Welcome/Housekeeping All talks: 10 mins (10 minutes for Q&A at the end of each session for all speakers in that session) Session 1: Exploration and Future Missions 1 Chair: Wim van Westrenen SN Time Abstract Author Title # 1 09:00 017 Messina, P. -

Earth's Wet Moon, an Icy Mars

Jet OCTOBER Propulsion 2009 Laboratory VOLUME 39 NUMBER 10 Lab discoveries find Earth’s wet moon, an icy Mars Data from three spacecraft confirm water Reconnaissance orbiter sees frozen water molecules on lunar surface exposed by meteor impacts Three JPL instruments have played our understanding of the moon. This a central role in the discovery of wa- exceptional accomplishment rests on ter molecules in the polar regions of the state-of-the-art M3 spectrometer the moon—a possibility long imagined developed at JPL and is a tribute to the by scientists that could help provide Laboratory’s commitment to the suc- resources for future humans living on cess of such a complex international Earth’s natural satellite. collaboration.” The JPL-managed Moon Mineralogy “These intriguing results,” added JPL Mapper, or M3, instrument reported the Planetary Science Instruments Manager observations. M3 was launched Oct. 22, Chris Webster, “remind us of the great 2008, aboard the Indian Space Research richness in science discovery that ac- Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter‘s HIRISE camera took these images of a fresh, 6-meter-wide crater on Oct. 18, 2008 (left) and on Organization’s Chandrayaan-1 space- companies every planetary mission Jan. 14, 2009. Each image is 35 meters across. This crater’s depth is estimated to be 1.33 meters. The impact exposed water ice—the bright material visible in this pair of images—from below the surface. craft. Data from the Visual and Infrared that we conduct; even to our nearest Mapping Spectrometer on JPL’s Cassini neighbor that we thought was well In a fortuitous and unexpected discov- beneath Mars’ surface halfway between spacecraft and the High-Resolution understood.” ery, JPL’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter the north pole and the equator, a lower Infrared Imaging Spectrometer on the M3’s spectrometer measured light re- has revealed frozen water hiding just latitude than expected in the Martian JPL-managed Epoxi spacecraft contrib- flecting off the moon’s surface at infra- below the surface of the Red Planet’s climate. -

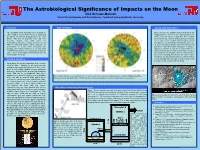

Dirk Schulze-Makuch Center for Astronomy and Astrophysics, Technical University Berlin, Germany

The Astrobiological Significance of Impacts on the Moon Dirk Schulze-Makuch Center for Astronomy and Astrophysics, Technical University Berlin, Germany Introduction Water on the Moon An Early Lunar Hydrosphere? The possibility for the formation of ice deposits or Water seems to be more abundant in lunar rocks than previously other volatiles on the Moon has been suggested thought (6) and some of the rocks also contain phyllosilicates (7), previously, not only by degassing form the early evidence of an early exposure to liquid water. This observation Moon, but also by deposition from water-rich may be linked to vapor transport during degassing of a magmatic meteorite impacts near lunar poles (1). source region, or from a hybrid endogenic-exogenic process Temperatures have been estimated to not exceed when gases were released during an impacting asteroid or comet 40K in shadowed Moon craters allowing the (8). A more speculative suggestion would be the existence of an preservation of frozen water molecules over early Moon or Earth-Moon system hydrosphere, or perhaps a geologic time scales. Presence of ice has been significant accumulation of water after an impact. Evidence for verified based on data from various space missions larger-scale hydrological processes would be hard to find since (e.g., Figure 1) and radar measurements with the any resulting surface topography would be long erased by 4 Arecibo radio telescope. billion years of pounding with solar wind and cosmic radiation. Nevertheless, the idea should be tested as it would be beneficial Importance of Lunar Ice to know what happened to the water on the Moon early on, how much water the Moon retained, and for how long. -

Akhtar Jawad - Poems

Poetry Series Akhtar Jawad - poems - Publication Date: 2015 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Akhtar Jawad(8-2-1945) I was born on 8th of February,1945 at 8 AM www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive 1 3d Computer Program A great scientist on his flying horse, Orbiting in a very big elliptical orbit, Once upon a time came very close, To my insignificant too small orbit, My small path he almost touched, Remained for quiet some times, In touch and in love as well, Took samples of my soil, Took samples of my air, Took samples of my fire, Took samples of my water, And finally samples of my light. He is a great artist, Painted a picture of mine, On a white canvas of love, And when I delivered a child, He took my child, To a beautiful garden, A garden of flowers, And the fruits, But my son was alone, All praise to the cloning, His mate was created. My son tasted the pleasant fruit, Pre-matured and before the time, And they were sent back, To me once again! With pains and blood, And undesired death! And when ugliness blackened my face, He sent his robots, At my thoughtful soil, The autumn was changed, In a spring for some time, His voice messages, Were played on flutes, www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive 2 In the bells that ring, At dawn and dusk, And in the loud human voices, All the tunes inspire to love, And paint the beauty, Of the great scientist! Now he is too far, In a path out of reach, The robots don't come, But the loving scientist, Expects from the two, Now matured enough, To keep my face, Neat and clean, Green and fertile, And let evolution, To travel on a path, That leads to a land, Where death is dead, I am aware of success, I am aware of failures, I am a mother, I know my children. -

Wet Moon, Lucky Moon

Home / Space/ Specials Wet moon, lucky moon On Monday 26 October 2020, NASA revealed a sensational discovery about our Moon: there is definitely water, also on its sunlit surface. The announcement was made with a press conference streamed at 5 p.m. Italian time. The notion that there is water on the Moon was more than just a suspicion, but the SOFIA airborne observatory has now spotted it at the bottom of a crater, where the temperature is -200°C because it is never exposed to sunlight. But don’t imagine lakes and rivers: the water is formed of tiny crystals mixed with regolith, lunar sand. SOFIA (Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy) is equipped with a 2.5-metre diameter telescope installed on a Boeing 747, a large airliner with no passenger seats and a big opening in the fuselage: the window through which the telescope overlooks the sky. The plane flies at an altitude of 12,000 metres: here, the rarefied, transparent air makes it possible to record extraordinarily high-quality observations. The presence of water on the Moon is encouraging for the scientists of the Artemis project, which will take a pair of astronauts, a woman and a man, to walk on the satellite by 2024 and, perhaps, the first crew on Mars in 2030. Indeed, the Moon could become an intermediate stage on the great journey from Earth to the Red Planet: the lunar water could quench the astronauts’ thirst and irrigate the space gardens. The NASA website contains wonderful detailed descriptions of all the equipment and technologies that will bring humanity back to the Moon 50 years after the last walk.