Title of Thesis Or Dissertation, Worded

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

©Copyright 2012 Sachi Schmidt-Hori

1 ©Copyright 2012 Sachi Schmidt-Hori 2 Hyperfemininities, Hypermasculinities, and Hypersexualities in Classical Japanese Literature Sachi Schmidt-Hori A Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2012 Reading Committee: Paul S. Atkins, Chair Davinder L. Bhowmik Tani E. Barlow Kyoko Tokuno Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Department of Asian Languages and Literature 3 University of Washington Abstract Hyperfemininities, Hypermasculinities, and Hypersexualities in Classical Japanese Literature Sachi Schmidt-Hori Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Associate Professor Paul S. Atkins Asian Languages and Literature This study is an attempt to elucidate the complex interrelationship between gender, sexuality, desire, and power by examining how premodern Japanese texts represent the gender-based ideals of women and men at the peak and margins of the social hierarchy. To do so, it will survey a wide range of premodern texts and contrast the literary depictions of two female groups (imperial priestesses and courtesans), two male groups (elite warriors and outlaws), and two groups of Buddhist priests (elite and “corrupt” monks). In my view, each of the pairs signifies hyperfemininities, hypermasculinities, and hypersexualities of elite and outcast classes, respectively. The ultimate goal of 4 this study is to contribute to the current body of research in classical Japanese literature by offering new readings of some of the well-known texts featuring the above-mentioned six groups. My interpretations of the previously studied texts will be based on an argument that, in a cultural/literary context wherein defiance merges with sexual attractiveness and/or sexual freedom, one’s outcast status transforms into a source of significant power. -

A World Like Ours: Gay Men in Japanese Novels and Films

A WORLD LIKE OURS: GAY MEN IN JAPANESE NOVELS AND FILMS, 1989-2007 by Nicholas James Hall A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Asian Studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) December 2013 © Nicholas James Hall, 2013 Abstract This dissertation examines representations of gay men in contemporary Japanese novels and films produced from around the beginning of the 1990s so-called gay boom era to the present day. Although these were produced in Japanese and for the Japanese market, and reflect contemporary Japan’s social, cultural and political milieu, I argue that they not only articulate the concerns and desires of gay men and (other queer people) in Japan, but also that they reflect a transnational global gay culture and identity. The study focuses on the work of current Japanese writers and directors while taking into account a broad, historical view of male-male eroticism in Japan from the Edo era to the present. It addresses such issues as whether there can be said to be a Japanese gay identity; the circulation of gay culture across international borders in the modern period; and issues of representation of gay men in mainstream popular culture products. As has been pointed out by various scholars, many mainstream Japanese representations of LGBT people are troubling, whether because they represent “tourism”—they are made for straight audiences whose pleasure comes from being titillated by watching the exotic Others portrayed in them—or because they are made by and for a female audience and have little connection with the lives and experiences of real gay men, or because they circulate outside Japan and are taken as realistic representations by non-Japanese audiences. -

Illustration and the Visual Imagination in Modern Japanese Literature By

Eyes of the Heart: Illustration and the Visual Imagination in Modern Japanese Literature By Pedro Thiago Ramos Bassoe A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy in Japanese Literature in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Daniel O’Neill, Chair Professor Alan Tansman Professor Beate Fricke Summer 2018 © 2018 Pedro Thiago Ramos Bassoe All Rights Reserved Abstract Eyes of the Heart: Illustration and the Visual Imagination in Modern Japanese Literature by Pedro Thiago Ramos Bassoe Doctor of Philosophy in Japanese Literature University of California, Berkeley Professor Daniel O’Neill, Chair My dissertation investigates the role of images in shaping literary production in Japan from the 1880’s to the 1930’s as writers negotiated shifting relationships of text and image in the literary and visual arts. Throughout the Edo period (1603-1868), works of fiction were liberally illustrated with woodblock printed images, which, especially towards the mid-19th century, had become an essential component of most popular literature in Japan. With the opening of Japan’s borders in the Meiji period (1868-1912), writers who had grown up reading illustrated fiction were exposed to foreign works of literature that largely eschewed the use of illustration as a medium for storytelling, in turn leading them to reevaluate the role of image in their own literary tradition. As authors endeavored to produce a purely text-based form of fiction, modeled in part on the European novel, they began to reject the inclusion of images in their own work. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Soteriology in the Female

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Soteriology in the Female-Spirit Noh Plays of Konparu Zenchiku DISSERTATION submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSPHY in East Asian Languages and Literatures by Matthew Chudnow Dissertation Committee: Associate Professor Susan Blakeley Klein, Chair Professor Emerita Anne Walthall Professor Michael Fuller 2017 © 2017 Matthew Chudnow DEDICATION To my Grandmother and my friend Kristen オンバサラダルマキリソワカ Windows rattle with contempt, Peeling back a ring of dead roses. Soon it will rain blue landscapes, Leading us to suffocation. The walls structured high in a circle of oiled brick And legs of tin- Stonehenge tumbles. Rozz Williams Electra Descending ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iv CURRICULUM VITAE v ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION vi INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: Soteriological Conflict and 14 Defining Female-Spirit Noh Plays CHAPTER 2: Combinatory Religious Systems and 32 Their Influence on Female-Spirit Noh CHAPTER 3: The Kōfukuji-Kasuga Complex- Institutional 61 History, the Daijōin Political Dispute and Its Impact on Zenchiku’s Patronage and Worldview CHAPTER 4: Stasis, Realization, and Ambiguity: The Dynamics 95 of Nyonin Jōbutsu in Yōkihi, Tamakazura, and Nonomiya CONCLUSION 155 BIBLIOGRAPHY 163 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation is the culmination of years of research supported by the department of East Asian Languages & Literatures at the University of California, Irvine. It would not have been possible without the support and dedication of a group of tireless individuals. I would like to acknowledge the University of California, Irvine’s School of Humanities support for my research through a Summer Dissertation Fellowship. I would also like to extend a special thanks to Professor Joan Piggot of the University of Southern California for facilitating my enrollment in sessions of her Summer Kanbun Workshop, which provided me with linguistic and research skills towards the completion of my dissertation. -

L2 Japanese Learners' Responses to Translation, Speed Reading

Reading in a Foreign Language April 2017, Volume 29, No. 1 ISSN 1539-0578 pp. 113–132 L2 Japanese learners’ responses to translation, speed reading, and ‘pleasure reading’ as a form of extensive reading Mitsue Tabata-Sandom Massey University New Zealand Abstract Fluency development instruction lacks in reading in Japanese as a foreign language instruction. This study examined how 34 upper-intermediate level learners of Japanese responded when they first experienced pleasure reading and speed reading. The participants also engaged in intensive reading, the main component of which was translation. Survey results indicated that the two novel approaches were more welcomed than translation. There was a positive correlation between the participants’ favorable ratings of pleasure reading and speed reading. The participants exhibited flexibility toward the two novel approaches in that they were willing to be meaningfully engaged in pleasure reading, whereas they put complete understanding before fluent reading when speed reading. The latter phenomenon may be explained by their predominantly- accuracy-oriented attitudes, fostered by long-term exposure to the grammar-translation method. The study’s results imply that key to successful fluency development is an early start that nurtures well-rounded attitudes toward the target language reading. Keywords: fluency development, learners of Japanese, pleasure reading, speed reading, translation Grabe (2009) maintained that fluency instruction is generally neglected in second and foreign language (L2) reading pedagogy. L2 reading classes have traditionally tended to employ an intensive reading approach (Sakurai, 2015), and L2 Japanese reading classes are no exception (Nishigoori, 1991; Tabata-Sandom, 2013, 2015). In such traditional approaches, learners are expected to perfectly understand a given text which is often above their current proficiency level even if they have to spend a tremendous amount of time on translating a given text. -

Introduction This Exhibition Celebrates the Spectacular Artistic Tradition

Introduction This exhibition celebrates the spectacular artistic tradition inspired by The Tale of Genji, a monument of world literature created in the early eleventh century, and traces the evolution and reception of its imagery through the following ten centuries. The author, the noblewoman Murasaki Shikibu, centered her narrative on the “radiant Genji” (hikaru Genji), the son of an emperor who is demoted to commoner status and is therefore disqualified from ever ascending the throne. With an insatiable desire to recover his lost standing, Genji seeks out countless amorous encounters with women who might help him revive his imperial lineage. Readers have long reveled in the amusing accounts of Genji’s romantic liaisons and in the dazzling descriptions of the courtly splendor of the Heian period (794–1185). The tale has been equally appreciated, however, as social and political commentary, aesthetic theory, Buddhist philosophy, a behavioral guide, and a source of insight into human nature. Offering much more than romance, The Tale of Genji proved meaningful not only for men and women of the aristocracy but also for Buddhist adherents and institutions, military leaders and their families, and merchants and townspeople. The galleries that follow present the full spectrum of Genji-related works of art created for diverse patrons by the most accomplished Japanese artists of the past millennium. The exhibition also sheds new light on the tale’s author and her female characters, and on the women readers, artists, calligraphers, and commentators who played a crucial role in ensuring the continued relevance of this classic text. The manuscripts, paintings, calligraphy, and decorative arts on display demonstrate sophisticated and surprising interpretations of the story that promise to enrich our understanding of Murasaki’s tale today. -

The Fascination of Japanese Traditional Books 大橋 正叔(Ôhashi Tadayoshi) Vice-President , Tenri University (1)Introduction Mr

The Fascination of Japanese Traditional Books 大橋 正叔(Ôhashi Tadayoshi) Vice-President , Tenri University (1)Introduction Mr. Chairman, Ladies and Gentlemen: My name is Tadayoshi Ohashi of Tenri University. It gives me great pleasure in presenting the SOAS Brunei Gallery exhibition of “ART OF JAPANESE BOOKS”. These are some of the Kotenseki 古典籍(Japanese Antiquarian materials) treasures from the Tenri Central Library 天理図書館.It is an honour to have the opportunity to speak before you at this joint cultural event of SOAS and Tenri University. Today I Wish to talk about the attractions of KotensekiI. Wherever they come from, antiquarian books are beautiful in their own styles and traditions. Japanese antiquarian books, however, are very unique in their diversities; namely, the binding-forms and paper-materials used, not to mention the wide range of calligraphic and multi-coloured printing techniques. For your reference I have enclosed a copy of bibliographical research sheet of the National Institute of Japanese Literature 国文学研究資料館. This is the sheet We use When We conduct research on Kotenseki. This sheet is dual-format applicable for both printed books and manuscripts. But there is single purpose format either for printed books or for manuscripts. The reason Why I am shoWing you this is, that I believe that this research sheet encapsulates the essence of Kotenseki(Japanese Antiquarian materials). I am going to discuss each style one by one. I am careful in using the word KOTENSEKI rather than the more usual Word HON. Kotenseki includes not only HON (books, manuscripts and records) but also the materials written on 短冊 Tanzaku(a strip of oblong paper mainly used for Writing Waka 和歌)or Shikishi 色紙(a square of high- quality paper). -

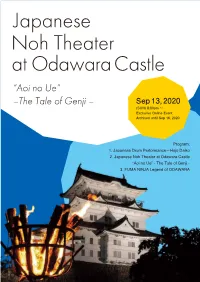

Aoi No Ue” –The Tale of Genji – Sep 13, 2020 (SUN) 8:00Pm ~ Exclusive Online Event Archived Until Sep 16, 2020

Japanese Noh Theater at Odawara Castle “Aoi no Ue” –The Tale of Genji – Sep 13, 2020 (SUN) 8:00pm ~ Exclusive Online Event Archived until Sep 16, 2020 Program: 1. Japanese Drum Performance—Hojo Daiko 2. Japanese Noh Theater at Odawara Castle “Aoi no Ue” - The Tale of Genji - 3. FUMA NINJA Legend of ODAWARA The Tale of Genji is a classic work of Japanese literature dating back to the 11th century and is considered one of the first novels ever written. It was written by Murasaki Shikibu, a poet, What is Noh? novelist, and lady-in-waiting in the imperial court of Japan. During the Heian period women were discouraged from furthering their education, but Murasaki Shikibu showed great aptitude Noh is a Japanese traditional performing art born in the 14th being raised in her father’s household that had more of a progressive attitude towards the century. Since then, Noh has been performed continuously until education of women. today. It is Japan’s oldest form of theatrical performance still in existence. The word“Noh” is derived from the Japanese word The overall story of The Tale of Genji follows different storylines in the imperial Heian court. for“skill” or“talent”. The Program The themes of love, lust, friendship, loyalty, and family bonds are all examined in the novel. The The use of Noh masks convey human emotions and historical and Highlights basic story follows Genji, who is the son of the emperor and is left out of succession talks for heroes and heroines. Noh plays typically last from 2-3 hours and political reasons. -

Catalogue 229 Japanese and Chinese Books, Manuscripts, and Scrolls Jonathan A. Hill, Bookseller New York City

JonathanCatalogue 229 A. Hill, Bookseller JapaneseJAPANESE & AND Chinese CHINESE Books, BOOKS, Manuscripts,MANUSCRIPTS, and AND ScrollsSCROLLS Jonathan A. Hill, Bookseller Catalogue 229 item 29 Catalogue 229 Japanese and Chinese Books, Manuscripts, and Scrolls Jonathan A. Hill, Bookseller New York City · 2019 JONATHAN A. HILL, BOOKSELLER 325 West End Avenue, Apt. 10 b New York, New York 10023-8143 telephone: 646-827-0724 home page: www.jonathanahill.com jonathan a. hill mobile: 917-294-2678 e-mail: [email protected] megumi k. hill mobile: 917-860-4862 e-mail: [email protected] yoshi hill mobile: 646-420-4652 e-mail: [email protected] member: International League of Antiquarian Booksellers, Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association of America & Verband Deutscher Antiquare terms are as usual: Any book returnable within five days of receipt, payment due within thirty days of receipt. Persons ordering for the first time are requested to remit with order, or supply suitable trade references. Residents of New York State should include appropriate sales tax. printed in china item 24 item 1 The Hot Springs of Atami 1. ATAMI HOT SPRINGS. Manuscript on paper, manuscript labels on upper covers entitled “Atami Onsen zuko” [“The Hot Springs of Atami, explained with illustrations”]. Written by Tsuki Shirai. 17 painted scenes, using brush and colors, on 63 pages. 34; 25; 22 folding leaves. Three vols. 8vo (270 x 187 mm.), orig. wrappers, modern stitch- ing. [ Japan]: late Edo. $12,500.00 This handsomely illustrated manuscript, written by Tsuki Shirai, describes and illustrates the famous hot springs of Atami (“hot ocean”), which have been known and appreciated since the 8th century. -

Japanese Children's Books 2020 JBBY's Recommendations for Young Readers Throughout the World

JAPANESE BOARD ON BOOKS FOR YOUNG PEOPLE Japanese 2020 Children's Books 2020 Cover illustration Japanese Children's Books Chiki KIKUCHI Born in 1975 in Hokkaido. After working at a design Contents firm, he decided at age 33 to become a picture book artist. His book Shironeko kuroneko (White ● Book Selection Team ................................................................................................2 Cat, Black Cat; Gakken Plus) won a Golden Apple ● About JBBY and this Catalog ................................................................................ 3 at the 2013 Biennial of Illustrations Bratislava (BIB), and his book Momiji no tegami (Maple Leaf Letter; ● Recent Japanese Children's Books Recommended by JBBY ......................4 Komine Shoten) won a plaque at the 2019 BIB. His ● The Hans Christian Andersen Award other works include Boku da yo, boku da yo (It’s Me, Five winners and 12 nominees from Japan It’s Me; Rironsha), Chikiban nyaa (Chiki Bang Meow; ........................................................20 Gakken Plus), Pa-o-po no uta (Pa-o-po Song; Kosei ● Japanese Books Selected for the IBBY Honour List ...................................22 Shuppan), Tora no ko Torata (Torata the Tiger Cub; Children’s Literature as a Part of Japan’s Publishing Statistics ....................... Shogakukan), and Shiro to kuro (White and Black; ● Essay: 24 Kodansha). ● Recent Translations into Japanese Recommended by JBBY ....................26 JBBY Book Selection and Review Team The JBBY Book Selection and Review Team collaboratively chose the titles listed in this publication. The name in parentheses after each book description is the last name of the team member who wrote the description. Yasuko DOI Director and senior researcher at the International Insti- Yukiko HIROMATSU tute for Children’s Literature (IICLO). Besides researching Picture book author, critic, and curator. -

Kuronet: Pre-Modern Japanese Kuzushiji Character Recognition with Deep Learning

KuroNet: Pre-Modern Japanese Kuzushiji Character Recognition with Deep Learning Tarin Clanuwat* Alex Lamb* Asanobu Kitamoto Center for Open Data in the Humanities MILA Center for Open Data in the Humanities National Institute of Informatics Universite´ de Montreal´ National Institute of Informatics Tokyo, Japan Montreal, Canada Tokyo, Japan [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Abstract—Kuzushiji, a cursive writing style, had been used in documents is even larger when one considers non-book his- Japan for over a thousand years starting from the 8th century. torical records, such as personal diaries. Despite ongoing Over 3 millions books on a diverse array of topics, such as efforts to create digital copies of these documents, most of the literature, science, mathematics and even cooking are preserved. However, following a change to the Japanese writing system knowledge, history, and culture contained within these texts in 1900, Kuzushiji has not been included in regular school remain inaccessible to the general public. One book can take curricula. Therefore, most Japanese natives nowadays cannot years to transcribe into modern Japanese characters. Even for read books written or printed just 150 years ago. Museums and researchers who are educated in reading Kuzushiji, the need libraries have invested a great deal of effort into creating digital to look up information (such as rare words) while transcribing copies of these historical documents as a safeguard against fires, earthquakes and tsunamis. The result has been datasets with as well as variations in writing styles can make the process hundreds of millions of photographs of historical documents of reading texts time consuming. -

Retrieval Chart: Woodblock Prints by Ando Hiroshige

www.colorado.edu/ptea-curriculum/imaging-japanese-history Handout T1 Page 1 of 2 Retrieval Chart: Woodblock Prints by Ando Hiroshige As your teacher shows each image, record what you observe in the center column of the table below. As you study the images, make notations about structures and technology, human activity, and trade and commerce. Image What Do I Observe in This Image? How Do These Observations Help Me Title Understand the Tokugawa Period? Nihonbashi Shinagawa Goyu Okazaki Seki Clearing Weather after Snow at Nihon Surugach The River Bank by Rygoku Bridge Fireworks at Rygoku Handout T1 Page 2 of 2 After you have studied all nine images, think about how your observations support and extend the ideas about the Tokugawa Period provided in Quotes 1 and 2. Write two or three sentences in the righthand column of the table explaining how evidence from the prints helps you better understand the Tokugawa Period. Quote 1 The flourishing of the Gokaid [five major highways] was largely supported by the alternate residence system (Sankin ktai) whereby feudal lords (daimy) were compelled to travel annually to Edo, where they kept their families and residences. The formal travelling procedure required many followers and a display of wealth demonstrating their high status. Various categories of inns . were built at each station to accommodate the daimy processions. Many local merchants and carriers were employed to serve them. Consequently, the regions close to the roads benefited economically from the flow of people and trade. The Gokaid, and especially the Tkaid, became sites of social diversity, where people from different classes and regions met.