Double Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chassidus on the Eh're Chassidus on the Parsha +

LIGHTS OF OUR RIGHTEOUS TZADDIKIM בעזרת ה ' יתבר A Tzaddik, or righteous person , makes everyone else appear righteous before Hashem by advocating for them and finding their merits. Kedushas Levi, Parshas Noach (Bereishis 7:1) RE ’EH _ CHASSIDUS ON THE PARSHA + Dvar Torah The Merit of Charity Compound forms of verbs usually indicate thoroughness. Yet when the Torah tells us (14:22), “You shall fully tithe ( aser te’aser ) all the produce of your field,” our Sages derive another concept. “ Aser bishvil shetis’asher ,” they say. “Tithe in order that you shall become wealthy.” Why is this so? When the charity a person gives, explains Rav Levi Yitzchak, comes up to Heaven, its provenance is scrutinized. Why was this particular amount giv en to charity? Then the relationship to the full amount of the harvest is discovered. There is a ration of ten to one, and the amount given is one tenth of the total. In this way the entire harvest participates in the mitzvah but only in a secondary role. Therefore, if the charity was given with a full heart, the person giving the charity merits that the quality of his donation is elevated. The following year, the entire harvest is elevated from a secondary role to a primary role in the giving of the charit y. The amount of the previous year’s harvest then becomes only one tenth of the new harvest, and the giver becomes wealthy. n Story Unfortunately, there were all too many poor people who circulated among the towns and 1 Re ’eh / [email protected] villages begging for assistance in staving off starvation. -

Rov in a Time of Cholera - Jewish Review of Books

3/19/2020 Rov in a Time of Cholera - Jewish Review of Books Rov in a Time of Cholera By Elli Fischer March 19, 2020 Rabbi Eliyahu Guttmacher was about 35 years old, serving the community of Pleschen (today Pleszew, Poland) in his rst rabbinic appointment when cholera hit. This was the summer of 1831, and the second of ve cholera pandemics to strike during the 19th century. After its appearance in India, the disease spread west eventually from Russia to Poland and then to Prussia. It soon moved on to the British Isles and North America, killing hundreds of thousands of people. As the disease tore through his community, Rabbi Guttmacher wrote to his teacher, Rabbi Akiva Eger, the rabbi of Posen (Poznan). It is hard to overestimate the esteem in which the rabbinic world holds Rabbi Eger to this day. His glosses adorn every page of the standard editions of the Talmud and Shulchan Arukh, and his Talmudic discussions and halakhic rulings are masterpieces of analysis. Yet, when his disciple in Pleschen asked how to address the new scourge of cholera, Rabbi Akiva Eger answered with simple, practical advice. His letter, of course, reects 19th-century medical information, but it has rightly been making the rounds on Israeli social media and #FrumTwitter during the COVID-19 pandemic as an example of rabbinic leadership during a crisis: With the help of God, may He be blessed. Monday of the Torah reading of “Nitzavim,” 5531, Posen. To Rabbi Eliyahu . the Rabbi Guttmacher’s head of the rabbinical court . of the holy amulet. -

JO2004-V37-N04.Pdf

Now everyone can participate in the Seder, even if you or ycnu guests can't read Hebrew This user-friendly, handy, economical Haggadah includes the complete translation, detailed instructions, short comments and a transliteration that enables those who cannot read Hebrew to recite the Hebrew text. Every word of the traditional Hagaddah is transliterated in easy-to-follow English characters, enabling everybody at your table to say, sing, and celebrate each part of the Seder. No one will be left behind. Everyone's participation an enjoyment is enhanced with the all-new, user-friendly, TRANSLITERATED Hagaddah. Economically priced for bulk purchases. Rabbi Yechiel Spero's first book, Touched by a Story, took the world by storm and became an instant best-seller. Readers asked, "When is the next one coming out?" Ask no more. Here it is! Rabbi Spero has good taste, enthusiasm, passion, and talent - the per fect blend for a master storyteller, which he is. See for yourself with this magnificent new collection. If you read volume 1, you'll run, not walk, to get your copy of Volume 2. If not, stop denying yourself. JEWISH PARABLES The parable has long been a favorite and very effective tool of some of our leaders and teachers. Think of the Maggid of Dubno, the Chafetz Chaim, the Ben lsh Chai, Rabbi Shalom Schwadron - these great men were Mashal Masters, with the blessed knack of creating just the right story to make an essential point. Rabbi Yisroel Bronstein has learned their lessons well. In this valuable book, he has collected hundreds of parables from classic sources and arranged them by topic. -

The Facts About the Shimon Hatzaddik A/Ka “Sheikh Jarrah” Property Dispute

The Facts About the Shimon HaTzaddik a/ka “Sheikh Jarrah” Property Dispute Summary: The private (Jewish) owner of property brought eviction proceedings against Arab squatters and holdover tenants who failed to pay rent for decades. The current owner has a chain of title of voluntary purchases/sales that goes back to 1875, when two Jewish community trusts first bought the then-empty land. These ordinary eviction proceedings between private parties regarding 28 homes became a pretext to demonize Israel, perpetrate violent riots against Jews, and make bigoted demands that Israel override and ignore private property rights and discriminate against property owners simply because they are Jewish. In 1875, Two Jewish Religious Trusts Purchased the Shimon HaTzaddik Tomb and Surrounding Land: For centuries, Jews made pilgrimages to pray at the tomb of beloved 4th century BCE Kohen Gadol (high priest) Shimon HaTzadik (Simeon the Just), in Jerusalem, northeast of the Old City. In 1875, two Jewish trusts, the Sephardi Community Council and the (Ashkenazi) General Council of the Congregation of Israel (a.k.a the “General Committee of the Knesset of Israel”), purchased the tomb and nearby lands forming the “Shimon HaTzadik” and “Nahalat [Inheritance of] Shimon” neighborhoods. Palestine Chief Rabbi Avraham Ashkenazi and Jerusalem Chief Rabbi Meir Auerbach registered the property in the Ottoman land registry in 1875 and 1876. Dozens of poor Jewish families moved there and continued to live there. The Tomb of Simeon the Righteous ... chabad.org In the late 1800s, wealthy Arabs (including the al-Husseinis) created a nearby neighborhood that the Arabs called “Sheikh Jarrah,” centered around the tomb of Hussam al-Din al-Jarrahi, a 12th century Muslim physician to Saladin. -

[email protected]

טל: 03-5780130 (+972) נייד: 53-7127469 (+972) 53-4813234 (+972) [email protected] המכירה והתצוגה יתקיימו ב׳פנינת חמד׳ רח' שמגר 21 ירושלים התצוגה בימים: יום שני א' חשון 19-10-2020 16:00-20:00 יום שלישי ב' חשון 20-10-2020 12:00-18:00 אנגלית: הגב' מ. בלום המכירה ביום רביעי ג׳ חשון 21/10/20 עימוד ועיצוב גרפי: אביעד בן סימון בשעה: 19:00 כריכה קידמית: פריטים מס׳ 61, 62, 68, 77 כריכה אחורית: פריט מס׳ 124 Viewing will take place on Monday, 1 Cheshvan מחיר הקטלוג: ₪100. למנויים )4 קטלוגים(: Oct. 2020) and Tuesday, 2 Cheshvan (20 Oct. 2020) .₪350 19) בחו"ל: $150 )כולל משלוח( Monday, 18 Cheshvan / 19 October, 2019 4:00 PM – 8:00 PM Tuesday, 19 Cheshvan / 20 October, 2019 12:00 PM – 6:00 PM Catalogue Price: $30 Prices for a subscription include 4 The auction will take place on Wednesday, 3 Cheshvan catalogues plus air mail fees: $150 5781 (21 Oct. 2010)at 7:00 PM כל הזכויות שמורות © * הקטלוג טעון גניזה עקב המצב הבריאותי הלא ידוע יתכנו שינויים בנוגע לתצוגה ולמכירה באולם תוכן עניינים ספרי תורה וכתבי יד 5 ........................ Torah Scrolls and Manuscripts ספרי יסוד ודפוסים ראשונים Fundamental Books 11 ........................................ and First Editions גדולי ומאורי החסידות 27 ....................Chassidic Giants and Luminaries חכמי הקבלה וגאוני מזרח 47 ...................... Kabbalist Sages Torah Geniuses גדולי האחרונים וחכמי אשכנז 61 .............. Great Achronim and Ashkenazi Sages גדולי הונגריה וחכמיה 69 ....................Hungarian Luminaries and Sages גדולי הדורות וראשי הישיבות ספרי תורה וכתבי יד Leaders of the Generations Torah Scrolls and Manuscripts 83 ....................................... and Yeshiva Heads חפצי קודש מצדיקי הדורות 101 ............ -

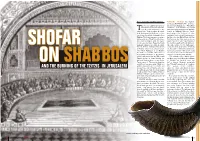

Blowing Shofar on Shabbos Is Forbidden Started Looking Around the Shul

Ari Z. Zivotofsky and Ari Greenspan Talmudic History Two enigmatic mishnayos (Rosh HaShanah 4:1–2) discuss his year it is unlikely that any of us the issue. The Mishnah says: “When Rosh will fulfill the mitzvah of shofar the HaShanah fell on Shabbos, they would Tway the Torah commands it. The blow in the Mikdash but not in the medinah mitzvah in the Torah is to blow the shofar [outside the Mikdash]. When the Temple on the first day of Rosh HaShanah, and this was destroyed, Rav Yochanan ben Zakai year the first day of Rosh HaShanah falls on established that they should blow anywhere Shabbos. This timing may not seem so rare, that has a beis din. Rabbi Elazar said that having occurred in five of the last ten years, Rav Yochanan ben Zakai made his decree but it will not happen again for another only in Yavneh; the other Sages responded eleven years, until 2020. Though the Torah that it applied equally to Yavneh and to any apparently obligates us to blow the shofar other place with a beis din. Furthermore, SHOFAR when the first day of Rosh HaShanah falls Jerusalem had one up on Yavneh in that any on Shabbos, Chazal decreed that in general, city that could see Jerusalem, could hear it, when Rosh HaShanah is on Shabbos was near it, and from which people could the shofar is not blown. Hence there is come to it on Yom Tov also blew, while in no d’Oraysa fulfillment of the mitzvah, Yavneh they blew only in the beis din.” which is only on the first day. -

מכירה מס' 21 שני י"ח כסלו התשע"ט 26/11/2018

מכירה מס' 21 שני י"ח כסלו התשע"ט 26/11/2018 1 פריטפריט: ItemItem: 040422 פריטפריט : ItemItem: 242400 פריט: Item: 234 פריט:פריט IteItemm: 224242 פריט: פריט ItItemem: 043043 פריט: Item: 222 פריט: Item: 278 פריט Item 278 פריט: פריט ItItemem: 228989 פריט: פריט ItItemem: 118686 פריט: Item: 236 פריט: Item: 209 פריט: Item: 179 2 בס"ד מכירה מס' 21 יודאיקה. כתבי יד. ספרי קודש. מכתבים. מכתבי רבנים חפצי יודאיקה. אמנות. פרטי ארץ ישראל. כרזות וניירת תתקיים אי"ה ביום שני יח' כסלו התשע"ט 26.11.2018, בשעה 18:00 המכירה והתצוגה המקדימה בבית מורשת רח' המלך ג'ורג' 43 ירושלים בימים: ג-ה 20-22.11.2018 א 25.11.2018 בין השעות 12:00-20:00 נשמח לראותכם ניתן לראות תמונות נוספות באתר מורשת www.moreshet-auctions.com טל: 02-5029020 פקס: 02-5029021 [email protected] אסף: 054-3053055 ניסים: 052-8861994 ניתן להשתתף בזמן המכירה אונליין דרך אתר בידספיריט )ההרשמה מראש חובה( https://moreshet.bidspirit.com בס"ד כסלו התשע"ט אל החברים היקרים והאהובים בשבח והודיה לה' יתברך על כל הטוב אשר גמלנו, הננו מתכבדים להציג בפניכם את קטלוג מכירה מס' 21. בקטלוג שלפניכם פריטי יודאיקה נדירים וחשובים: כתב יד מפואר על קלף. סדר קדוש לשבת לר' השנה ולשלוש רגלים. מקהילת אובן ישן. תר"ע | 1910. פריט היסטורי.. )פריט מס' 241(. כתב-יד חשוב 'זרע קדושים' חיבור שלם על התורה, אוטוגרף חתום - אירופה, ראשית המאה ה18-. תגלית היסטורית )פריט מס' 240(. כתב יד חיבור לא ידוע " יד יוסף" כתב היד היה בבעלותו של זקן המקובלים הרב מרדכי שרעבי זיע"א. )פריט מס' 242(. -

Download PDF Catalogue

F i n e Ju d a i C a . he b r e w pr i n t e d bo o K s , ma n u s C r i p t s , Gr a p h i C & Ce r e m o n i a l ar t in C l u d i n G : th e al F o n s o Ca s s u t o Co l l e C t i o n o F ib e r i a n -Ju d a i C a K e s t e n b a u m & Co m p a n y th u r s d a y , Fe b r u a r y 24t h , 2011 K e s t e n b a u m & Co m p a n y . Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art A Lot 264 Catalogue of F i n e Ju d a i C a . PRINTED BOOKS , MANUSCRI P TS , AUTOGRA P H LETTERS , GRA P HIC & CERE M ONIA L ART Featuring: Iberian Judaica The Distinguished Collection of the late Alfonso Cassuto of Lisbon, Portugal ——— To be Offered for Sale by Auction, Thursday, 24th February, 2011 at 3:00 pm precisely ——— Viewing Beforehand: Sunday, 20th February - 12:00 pm - 6:00 pm Monday, 21st February - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm Tuesday, 22nd February - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm Wednesday 23rd February - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm No viewing on the day of sale. -

A Reach Which Exceeds Its Grasp Lives of Israel's Rabbis: Rabbi

בס“ד Parshat Bereishit 27 Tishrei, 5777/October 29, 2016 Vol. 8 Num. 8 This issue of Toronto Torah is sponsored by Esther and Craig Guttmann in honour of the Bar Mitzvah of their son, Gilad Gomolin A Reach Which Exceeds its Grasp Adam Friedmann In Guide for the Perplexed (3:13) the our intellectual gifts. Greatness is also “very good” (1:31). Why the change? Rambam discusses the question of felt regarding man’s spiritual capacity. One possibility, explains this midrash Man’s place in the cosmos. Is man the We are geared for endless growth, and (Lekach Tov, Yalkut Shimoni), is that central purpose of creation, with in moments of forward momentum we the world cannot be “very good” without everything else having value only can become aware of the intimate bond Man. The crown of creation is insofar as it supports him? Or is man to G-d that He has afforded us. incomplete without its jewel. But a creature among others, playing a However, there are also moments of another explanation is that “very” refers particular role, however lofty, in a failure when we are forced to confront to death, suffering, and the yetzer hara. much larger system? Perhaps G-d’s the extent of our shortcomings. If the world is incomplete without man, other creations have independent Moments when it becomes clear just he, in turn, is incomplete without a reasons for existence unrelated and how tenuous a grip on our physical capacity to fail both physically and unbound to man’s. Rambam takes the surroundings we really have, and how spiritually. -

Chassidus on the Eh're Chassidus on the Parsha +

LIGHTS OF OUR RIGHTEOUS TZADDIKIM בעזרת ה יתבר ' ב עז רת ה A Tzaddik, or righteous person, makes everyone else appear righteous before Hashem by advocating for them and finding their merits. Kedushas Levi, Parshas Noach (Bereishis 7:1) EH’RE _ CHASSIDUS ON THE PARSHA + Dvar Torah The Merit of Charity Compound forms of verbs usually indicate thoroughness. Yet when the Torah tells us (14:22), “You shall fully tithe (aser te’aser) all the produce of your field,” our Sages derive another concept. “Aser bishvil shetis’asher,” they say. “Tithe in order that you shall become wealthy.” Why is this so? When the charity a person gives, explains Rav Levi Yitzchak, comes up to Heaven, its provenance is scrutinized. Why was this particular amount given to charity? Then the relationship to the full amount of the harvest is discovered. There is a ration of ten to one, and the amount given is one tenth of the total. In this way the entire harvest participates in the mitzvah but only in a secondary role. Therefore, if the charity was given with a full heart, the person giving the charity merits that the quality of his donation is elevated. The following year, the entire harvest is elevated from a secondary role to a primary role in the giving of the charity. The amount of the previous year’s harvest then becomes only one tenth of the new harvest, and the giver becomes wealthy. n Story Unfortunately, there were all too many poor people who circulated among the towns and 1 Re’eh / [email protected] villages begging for assistance in staving off starvation. -

Shaykh Jarrah

JERUSALEM Abstract NEIGHBORHOODS Tens of Palestinian refugee families face eviction from their homes Shaykh Jarrah in Jerusalem’s Shaykh Jarrah neighborhood after the claim that the A Struggle for Survival land on which their house was built in 1956 belonged to Jewish owners Nazmi Jubeh prior to 1948. Israeli law allows Jews to reclaim their properties within the 1967 occupied territories, but denies Palestinians the same right, despite the fact that, according to Israeli law, both Palestinians and Israelis in Jerusalem live under Israeli jurisdiction. By clearly exposing Israel’s apartheid policies, the struggle waged by this small Shaykh Jarrah neighborhood of twenty-eight houses could begin a new era in the Jerusalem front line of the Palestinian-Israel conflict. Keywords Shaykh Jarrah; Jewish settlements in East Jerusalem; Shimon HaTzadik; Holy Basin; displacement of Palestinians; Mufti of Jerusalem. The threatened evictions in Shaykh Jarrah are part of a larger plan to transform the main area of conflict, Jerusalem and its vicinity, into a Jewish Israeli city. The Israeli projects in the area known as the “Holy Basin” – encompassing the Old City and the surrounding area, including the holy sites and Jerusalem’s historical landscape – aim to change the demographic reality and urban landscape in Jerusalem in favor of the occupation and its religious and “nationalistic” symbols. The Shaykh Jarrah neighborhood cannot be separated from what is happening in al- Jerusalem Quarterly 86 [ 129 ] Aqsa Mosque, as was evident in the spring 2021 al-Aqsa uprising, since that holy site is the central part of this plan. In order to understand the Holy Basin’s importance and the ferociousness of the attack on it, it is enough to say that after fifty-four years of occupation of east Jerusalem, 90 percent of the population in the Old City and the “Holy Basin” is still Palestinian, despite the numerous mechanisms Israel has employed to change its composition in favor of the colonialist project. -

Kárpáti Judit, Ph.D. a Halukka. Néhány Gondolat Egy

Kárpáti Judit, Ph.D. A halukka. Néhány gondolat egy ellentmondásosnak vélt segélyezési rendszer kapcsán. The Halukkah. Various Thoughts about a Debatable Aid System ABSZTRAKT A 19. század végén a Szentföldön (akkori politikai nevén Palesztinában) gyakorlatilag háromféle zsidó csoport létezett: a Közel-Kelet térségének túlnyomó részben szefárd rítust követő zsidósága, akik közül számosan mondhatók palesztinai őshonosnak. A másik csoport, az akkorra már többségében Európából érkezett, mélyen vallásos közösségek számára Jeruzsálem és a szent városok mindenekfelett szellemi teret jelentenek: az Örökkévaló közelségének valósága itt a legkézzelfoghatóbb a számukra. A zsidó miszticizmus tanítása szerint a Szentföldön élni és imádkozni micva, s így, aki ezt vállalja, azt támogatni kell. Az ő jelenlétük a többi, Európában maradt zsidó jelenlétét is képviseli, így az otthon maradottaknak erkölcsi kötelessége támogatásuk. Az európai közösségek által a szentföldi közösségek számára összegyűjtött adományok elosztási rendszerét nevezik halukkának. Egy újabb, dinamikusan fejlődő csoport tagjai túlnyomórészt fiatalok, akik legfőbb célja egy önálló, független zsidó haza létrehozása Izrael földjén. A cionizmus ezen előfutárai, a galuti lét nagy tagadói számára a halukka – rendszer mélyen lealacsonyító, a zsidósághoz méltatlan intézmény. A cikk rövid áttekintést nyújt erről a vitatott támogatási rendszerről, a teljesség igénye nélkül, a fent említett zsidó csoportok álláspontjait is bemutatva. ABSTRACT It is a well-known fact that there are no dogmas in Judaism, however there are quite a few well- established ideas that cannot be questioned easily. One of these basic religious traditions has an utmost importance: the focal point of the Jewish religion is the Holy City of Jerusalem and the Land of the Holy One. This idea follows the Jews in their everyday religious practices from the womb to the grave.