Book of Mormon Language, Names, and [Metonymic] Naming

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reference Guides for Registering Students with Non English Names

Getting It Right Reference Guides for Registering Students With Non-English Names Jason Greenberg Motamedi, Ph.D. Zafreen Jaffery, Ed.D. Allyson Hagen Education Northwest June 2016 U.S. Department of Education John B. King Jr., Secretary Institute of Education Sciences Ruth Neild, Deputy Director for Policy and Research Delegated Duties of the Director National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance Joy Lesnick, Acting Commissioner Amy Johnson, Action Editor OK-Choon Park, Project Officer REL 2016-158 The National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance (NCEE) conducts unbiased large-scale evaluations of education programs and practices supported by federal funds; provides research-based technical assistance to educators and policymakers; and supports the synthesis and the widespread dissemination of the results of research and evaluation throughout the United States. JUNE 2016 This project has been funded at least in part with federal funds from the U.S. Department of Education under contract number ED‐IES‐12‐C‐0003. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the U.S. Department of Education nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. REL Northwest, operated by Education Northwest, partners with practitioners and policymakers to strengthen data and research use. As one of 10 federally funded regional educational laboratories, we conduct research studies, provide training and technical assistance, and disseminate information. Our work focuses on regional challenges such as turning around low-performing schools, improving college and career readiness, and promoting equitable and excellent outcomes for all students. -

Last Name First Name/Middle Name Course Award Course 2 Award 2 Graduation

Last Name First Name/Middle Name Course Award Course 2 Award 2 Graduation A/L Krishnan Thiinash Bachelor of Information Technology March 2015 A/L Selvaraju Theeban Raju Bachelor of Commerce January 2015 A/P Balan Durgarani Bachelor of Commerce with Distinction March 2015 A/P Rajaram Koushalya Priya Bachelor of Commerce March 2015 Hiba Mohsin Mohammed Master of Health Leadership and Aal-Yaseen Hussein Management July 2015 Aamer Muhammad Master of Quality Management September 2015 Abbas Hanaa Safy Seyam Master of Business Administration with Distinction March 2015 Abbasi Muhammad Hamza Master of International Business March 2015 Abdallah AlMustafa Hussein Saad Elsayed Bachelor of Commerce March 2015 Abdallah Asma Samir Lutfi Master of Strategic Marketing September 2015 Abdallah Moh'd Jawdat Abdel Rahman Master of International Business July 2015 AbdelAaty Mosa Amany Abdelkader Saad Master of Media and Communications with Distinction March 2015 Abdel-Karim Mervat Graduate Diploma in TESOL July 2015 Abdelmalik Mark Maher Abdelmesseh Bachelor of Commerce March 2015 Master of Strategic Human Resource Abdelrahman Abdo Mohammed Talat Abdelziz Management September 2015 Graduate Certificate in Health and Abdel-Sayed Mario Physical Education July 2015 Sherif Ahmed Fathy AbdRabou Abdelmohsen Master of Strategic Marketing September 2015 Abdul Hakeem Siti Fatimah Binte Bachelor of Science January 2015 Abdul Haq Shaddad Yousef Ibrahim Master of Strategic Marketing March 2015 Abdul Rahman Al Jabier Bachelor of Engineering Honours Class II, Division 1 -

Last Name First Name Middle Name Years of Service A

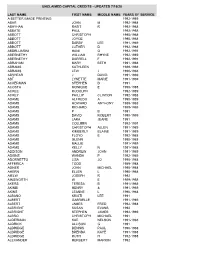

UNCLAIMED CAPITAL CREDITS - UPDATED 7/16/20 LAST NAME FIRST NAME MIDDLE NAME YEARS OF SERVICE A BETTER IMAGE PRINTING 1992-1989 ABAR JOHN M 1992-1988 ABAYHAN RASIT R 1992-1988 ABBATE PAUL 1992-1988 ABBOTT CHRISTOPH 1990-1988 ABBOTT JOYCE 1990-1988 ABBOTT DARBY LEE 1991-1989 ABBOTT LUTHER D 1992-1988 ABDELUARIM HANI O 1992-1991 ABERNETHY WILLIAM RHYNE 1992-1989 ABERNETHY DARRELL F 1992-1991 ABRAHAM MARY BETH 1991-1988 ABRAMS KATHLEEN 1989-1988 ABRAMS LEW J 1990-1988 ABSHEAR J DAVID 1991-1989 ABT LYNETTE MARIE 1991-1989 ACKERMAN STEPHEN D 1991 ACOSTA MONIQUE E 1990-1988 ACREE RUDOLPH 1992-1989 ACREY PHILLIP CLINTON 1992-1988 ADAME ALFREDO A 1990-1989 ADAMS HOWARD ANTHONY 1989-1988 ADAMS RICHARD 1989-1988 ADAMS P B 1991 ADAMS DAVID ROBERT 1990-1989 ADAMS LARA JEANE 1991 ADAMS COLLEEN 1992-1991 ADAMS CHRISTOPH ALLEN 1991-1989 ADAMS KIMBERLY ELAINE 1991-1989 ADAMS FLOYD E 1992-1988 ADAMS GLENN 1990-1988 ADAMS MALLIE 1991-1989 ADAMS KELLY N 1991-1988 ADDISON ANDREW JOHN 1991-1989 ADKINS WANDA P 1992-1989 ADORNETTO LISA JO 1990-1988 AFFERICA TODD 1989-1988 AGNER JOHN MICHAEL 1990-1988 AHERN ELLEN L 1990-1988 AIELW JOSEPH R 1992 AINSWORTH W E 1989-1988 AKERS TERESA B 1991-1988 AKINBI HENRY & 1991-1989 AKINS LEANNE L 1990-1988 ALBANO KRISTI LEE 1991 ALBERT GABRIELLE 1991-1989 ALBERT JAMES FRED 1992-1988 ALBRIGHT SUSAN EVANS 1992 ALBRIGHT STEPHEN JAMES 1992-1989 ALBRO CHRISTOPH MICHAEL 1991 ALDERMAN KAE NELSON 1991-1988 ALDRICK ALLISON G 1991 ALDRIDGE DENNIS PAUL 1990-1988 ALDRIDGE BRENDA KAYE 1991-1988 ALDRIDGE RUTH H 1992-1988 ALEXANDER HERBERT -

Metonymy and Multiple Naming in North American Indian Societies

Guy Lanoue Université de Montréal 1 Metonymy and Multiple Naming in North American Indian Societies Guy Lanoue Département d'anthropologie Université de Montréal In the Western tradition, names are everywhere iconic indicators of the autonomy of the persona, of the Self as a locus of emotional and existential resistance to the community. This has given rise to endless speculation about the manner in which proper names have signification even though most are deprived of lexical meanings (Wilson 1998:xi). Individual names therefore subvert the standard (largely Jakobsonian) theory of semantic codification (Marconi 2000) in which the relation of sign to signified is transmitted through the semantic content of the sign. To identify properly the subject of a simple sentence such as "John is at home" in order to gauge the truth of the assertion, a listener must know from the unspecified context to which "John" the speaker is referring, transforming "John" into a metonym of the category of proper names. Furthermore, for the sentence to be meaningful to the listener (which is not the same thing as its truth value, as Noam Chomsky has pointed out), the listener must invoke a second unspecified context, attaching to the name "John" visual and personality clues coded to that specific listener, i.e., the listener's memories of John. These clues in the listener's memory do not correspond to agreed-upon semantic conventions that constitute the referential pool that is determinative of the socially-'objective' knowledge beloved by Karl Popper's analytic approach and criticised (but in the end legitimated) by Wittgenstein. -

Male Names in X-Son in Brazilian Anthroponymy: a Morphological, Historical, and Constructional Approach

Revista de Estudos da Linguagem, v. 26, n. 3, p. 1295-1350, 2018 Male Names in X-Son in Brazilian Anthroponymy: a Morphological, Historical, and Constructional Approach Nomes masculinos X-son na antroponímia brasileira: uma abordagem morfológica, histórica e construcional Natival Almeida Simões Neto Universidade Estadual de Feira de Santana (UEFS), Feira de Santana, Bahia / Brasil [email protected] Juliana Soledade Universidade Federal da Bahia (UFBA), Salvador, Bahia / Brasil Universidade de Brasília (UnB), Brasília, DF / Brasil [email protected] Resumo: Neste trabalho, pretendemos fazer uma análise de nomes masculinos terminados em -son na lista de aprovados dos vestibulares de 2016 e 2017 da Universidade do Estado da Bahia, como Anderson, Jefferson, Emerson, Radson, Talison, Erickson e Esteferson. Ao todo, foram registrados 96 nomes graficamente diferentes. Esses nomes, quando possível, foram analisados do ponto de vista etimológico, com base em consultas nos dicionários onomásticos de língua portuguesa de Nascentes (1952) e de Machado (1981), além de dicionários de língua inglesa, como os de Arthur (1857) e Reaney e Willson (2006). Foram também utilizados como materiais de análise a Lista de nomes admitidos em Portugal, encontrada no site do Instituto dos Registos e do Notariado, de Portugal, e a Plataforma Nomes no Brasil, disponível no site do Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Quanto às análises morfológicas aqui empreendidas, utilizamos como aporte teórico-metodológico a Morfologia Construcional, da maneira proposta por Booij (2010), Soledade (2013), Gonçalves (2016a), Simões Neto (2016) e Rodrigues (2016). Em linhas gerais, o artigo vislumbra observar a trajetória do formativo –son na criação de antropônimos no Brasil. Para isso, eISSN: 2237-2083 DOI: 10.17851/2237-2083.26.3.1295-1350 1296 Revista de Estudos da Linguagem, v. -

7 Naming Customs from Around the World

7 Naming Customs From Around the World http://blog.tesol.org/7-naming-customs-from-around-the-world/ Posted on 30 July 2015 by Judie Haynes Immigrant students in the United States have already suffered the trauma of leaving behind their extended family, friends, teachers, and schools. They enter a U.S. school and can also lose their name. Their name may be deliberately changed by parents or school staff, or an error may be made in the order of the name or its spelling. These mistakes can have lasting effects on students. A person’s name is part of his or her cultural identity, and it is up to schools to get it right. In order for teachers, administrators, or office staff in your school to enroll students with the correct the name, they need to understand the naming conventions of different cultures. Here are seven naming customs from different cultures. Korean names are written with the family name first. If Yeon Suk has the family name “Lee,” his name will be written Lee Yeon Suk. The given name usually has two parts, and it follows the family name. Either part of the given name can be a generation marker: Two- part given names should not be shortened— that is, Lee Yeon Suk should be called Yeon Suk, not Yeon. Russian names have three parts: a given name, a patronymic (a middle name based on the father’s first name), and the father’s surname. If Viktor Aleksandrovich Rakhmaninov has two children, his daughter’s name would be Svetlana Viktorevna Rakhmaninova. -

Download Article (PDF)

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 447 Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference on Philosophy of Education, Law and Science in the Era of Globalization (PELSEG 2020) Stylistic Devices of Creating a Portrait of the Character Artistic Image (Based on the Work of Thomas Mayne Reid) V. Vishnevetskaya 1Novorossiysk Polytechnic Institute (branch) of Kuban State Technological University 20, ul. Karl Marx, Novorossiysk, 353900, Russia. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract —The article considers the stylistic devices used for II. MATERIALS AND METHODS the portrait description of the character of the artwork. It is necessary to emphasize that stylistic devices play quite an In our work, we use the methods of comparing and important role in creating the artistic image of the character. At contrasting which help the author to create special portrait of a the same time, stylistic devices mainly emphasize not only the character. Stylistic devices are important line elements of the specific features of the exterior, but also various aspects of the portrait description. The process of creating a character visual impression, while bringing to the forefront the features of portrait image uses all the existing stylistic devices that are the drawing image that seem important to the author for one used in the English language system. The most used stylistic reason or another. And, here, the emotional characteristic of the devices are metaphor, epithet, comparison, metonymy and portrait described is becoming significant, and the impression others. that the image formed by the author can make. Stylistic devices are an important line element of the portrait description. -

John Benjamins Publishing Company

John Benjamins Publishing Company This is a contribution from Conceptual Metonymy. Methodological, theoretical, and descriptive issues. Edited by Olga Blanco-Carrión, Antonio Barcelona, and Rossella Pannain. © 2018. John Benjamins Publishing Company This electronic file may not be altered in any way. The author(s) of this article is/are permitted to use this PDF file to generate printed copies to be used by way of offprints, for their personal use only. Permission is granted by the publishers to post this file on a closed server which is accessible to members (students and staff) only of the author’s/s’ institute, it is not permitted to post this PDF on the open internet. For any other use of this material prior written permission should be obtained from the publishers or through the Copyright Clearance Center (for USA: www.copyright.com). Please contact [email protected] or consult our website: www.benjamins.com Tables of Contents, abstracts and guidelines are available at www.benjamins.com Chapter 4 Some contrast effects in metonymy John Barnden University of Birmingham This chapter analyses important, variegated ways in which contrast arises in me- tonymy. It explores, for instance, the negative evaluation of the target achieved in de-roling, where the source chosen is a target feature that is largely irrele- vant to the target’s role in a described situation, therein contrasting with other target features that would have been more appropriate. This form of contrast, amongst others, can generate irony, so that the chapter elucidates some of the complex connections between metonymy and irony. It also explores the mul- tiple roles of contrast in transferred epithets, especially as transferred epithets can be simultaneously metonymic and metaphorical. -

Metonymy: the Way to Convey Information

ICOELT-6 Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on English Language and Teaching 2018 ȋ ǦȌ METONYMY: THE WAY TO CONVEY INFORMATION Yola Merina and Hevriani Sevrika Sekolah Tinggi Keguruan dan Ilmu Pendidikan (STKIP) PGRI Sumatera Barat e-mail: [email protected] 1) and [email protected] Abstract This research discussed about the use of metonymy in conveying information in college environment. The aim of this research is to find out the kinds of metonymy that used by speakers to another speaker in uttering, mentioning and delivering their thoughts. It is to understand the meaning of utterances that use metonymy which are spread out from speakers. This research was used qualitative approach. In obtaining the data, the researcher used non-participant observational technique with observational method. The following techniques in obtaining data were recording and note taking technique. The location sources of data were taken from utterances of students and lecturers. Based on theories provided, the data were analyzed one by one to know the type of metonymy used and the meaning of it. To focus on the study, the data were limited to be analyzed, only metonymy which were delivered by lecturers of English Department in STKIP PGRI were listened and recorded by researcher in college field during a month. From the analysis, this research found spatial, temporal and abstract as metonymy’s kinds which were used for conveying information. Keywords: contiguity, cognitive linguistics, entity, metonymy 1. INTRODUCTION In daily life, there are many ways of speaker use figure of speech in expressing and providing information through string of words that comes from someone’s thoughts and ideas. -

Metonymy, Metaphor, and Iconicity in Two Signed Languages

Jezikoslovlje █ 139 4.1 (2003): 139-156 UDC 81’221.24 81’373.612.2 Original scientific paper Received on 09. 06. 2004. Accepted for publication 23.06. 2004. 1 1 Sherman Wilcox, Phyllis Perrin Wilcox 2 & Maria Josep Jarque 1University of New Mexico Albuquerque 2Universitat de Barcelona Mappings in conceptual space: Metonymy, metaphor, and iconicity in two signed languages In this paper we present lexical data documenting the interaction of me- tonymy, metaphor, and iconicity in two signed languages, American Sign Language (ASL) and Catalan Sign Language (LSC). The basis of our analysis is the recognition that metonymy, metaphor, and iconicity all represent mappings across domains within a conceptual system. This framework also permits us to incorporate the form of signs, their pho- nological pole, as a region in conceptual space. The data examined ex- emplify several basic metonymies such as ACTION FOR INSTRUMENT and PROTOTYPICAL ACTION FOR ACTIVITY. We also examine cases in which gesture plays a role in metonymy. One area in which metonymy is quite extensively used in signed languages is in the creation of name signs. We explore various types of name signs and the metonymies involved in each. Finally, we examine two case studies of the complex interac- tion of metonymy, metaphor, and iconicity: the ASL epithet THINK- HEARING, and the LSC signs expressing the acquisition of ideas as IDEAS ARE LIQUID and knowledge as MIND IS A TORSO. We conclude that the deep interplay of metonymy, metaphor, and iconicity, as well as their cultural contextuality, requires that they be understood as con- ceptual space mappings. -

CM/ECF GUIDE for ENTERING PARTY NAMES United States

CM/ECF GUIDE FOR ENTERING PARTY NAMES United States District Court Northern District of Indiana Page i 1 Table of Contents 2 3 Section Page 4 No. No. 5 6 I. Party Name Entry 7 8 A. Entry of simple party names . 2 9 10 B. Abbreviations. 2 11 12 C. Agency/Business Names. 2 13 14 D. Estates as Parties. 4 15 16 E. Generations/Titles in Party/Attorney Name Entry.. 7 17 18 F. Money/Currency. 8 19 20 G. Party Text. 9 21 22 H. Punctuation.. 9 23 24 I. Real Estate/Property. 9 25 26 J. Social Security Cases (And Other Government Agency Cases). 10 27 28 K. Spanish Surnames. 10 29 30 L. State/Local Government Names.. 11 31 32 M. Street Address as a Party. 13 33 34 N. Telephone Number Entry. 14 35 36 O. Titles/Generations in Party/Attorney Name Entry.. 14 37 38 P. Union Names.. 14 39 40 Q. Unknown Heirs.. 15 Page ii 1 2 R. Unknown Spouses or Tenants.. 15 3 4 S. USA as a Party. 16 5 6 T. Vehicles. 16 7 8 U. Alias names.. 16 9 Page 1 1 2 3 I. Party Name Entry. 4 5 The three ultimate goals regarding the entry of party names into the system are: 1) To only 6 have one version of a particular name (a recurring name) in the system; 2) To make similar, 7 but slightly differing, names unique enough so that they are recognizable; and 3) To be able 8 to retrieve names in a logical way. -

1 Personal Data Position Desired Employment History **OFFICE USE

**OFFICE USE ONLY** o New Applicant o Transfer Applicant o Reemployment Applicant This council is an equal opportunity employer. All applications for employment will be considered without regard to race, religion, color, sex, age, national origin, citizenship, disability or marital status or any other protected class. Personal Data Last Name First Name Middle Name or Initial Date of Application Present Address (Number and Street) City State Zip Code Area Code & Telephone # Permanent Address (If different from above) City State Zip Code Area Code & Telephone # E-mail address Position Desired Position/Type of Work Desired o Regular oFull Time Date Available Salary Desired o Temporary o Part Time Source of referral: Agency (name) Own Initiative Publication (name) Employee (name) School/Organization Other Willing to Travel? Percentage of Time: Willing to Relocate? Geographic Preference Do you have relatives o Yes o No o Yes o No employed by GSUSA or a Girl Scout Council? o Yes o No Were you ever employed by GSUSA or a Girl Scout Council: Have you previously applied to GSUSA or a Girl Scout Council? o Yes o No When? Where? o Yes o No When? Where? If hired are you able to show proof that you are legally eligible to work in the United States? o Yes o No If it is a condition of employment will you be willing to submit to a credit and/or criminal background check? o Yes o No Employment History Present or Last Employer Name of Employer Title or Position Address City State Zip Code Area Code & Tel. # Employment Dates (Mo.