Onomastics Between Sacred and Profane

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Adoption of Non-Chinese Names As Identity Markers of Chinese International Students in Japan: a Case Study at a Japanese Comprehensive Research University

The Adoption of non-Chinese Names as Identity Markers of Chinese International Students in Japan: A Case Study at a Japanese Comprehensive Research University Jinyan Chen Kyushu University, Fukuoka, JAPAN ans-names.pitt.edu ISSN: 0027-7738 (print) 1756-2279 (web) Vol. 69, Issue 2, Spring 2021 DOI 10.5195/names.2021.2239 Articles in this journal are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. This journal is published by the University Library System of the University of Pittsburgh as part of its D-Scribe Digital Publishing Program and is cosponsored by the University of Pittsburgh Press. 12 NAMES: A JOURNAL OF ONOMASTICS Jinyan Chen Abstract This study explores naming practices among Chinese international students and their relation to personal identity during their sojourn in Japan. Although previous studies have reported that some Chinese international students in English-speaking countries adopt names of Western origin (Cotterill 2020; Diao 2014; Edwards 2006), participants in this study were found to exhibit different naming practices: either adopting names of Japanese or Western origin; or retaining both Western and Japanese names. Drawing on fifteen semi-structured interviews with Mainland Han Chinese students, this investigation examines their motivations for adopting non- Chinese names and determines how personal identities are presented through them. The qualitative analysis reveals that the practice of adopting non-Chinese names is influenced by teacher-student power relations, Chinese conventions for terms of address, pronunciation, and context-sensitivity of personal names. As will be shown in this article, through the respondents’ years of self- exploration, their self-adopted non-Chinese names gradually became internalized personal identity markers that allow the bearers to explore and exhibit personality traits, which might not have been as easily displayed via their Chinese given names. -

International Naming Conventions NAFSA TX State Mtg

1 2 3 4 1. Transcription is a more phonetic interpretation, while transliteration represents the letters exactly 2. Why transcription instead of transliteration? • Some English vowel sounds don’t exist in the other language and vice‐versa • Some English consonant sounds don’t exist in the other language and vice‐versa • Some languages are not written with letters 3. What issues are related to transcription and transliteration? • Lack of consistent rules from some languages or varying sets of rules • Country variation in choice of rules • Country/regional variations in pronunciation • Same name may be transcribed differently even within the same family • More confusing when common or religious names cross over several countries with different scripts (i.e., Mohammad et al) 5 Dark green countries represent those countries where Arabic is the official language. Lighter green represents those countries in which Arabic is either one of several official languages or is a language of everyday usage. Middle East and Central Asia: • Kurdish and Turkmen in Iraq • Farsi (Persian) and Baluchi in Iran • Dari, Pashto and Uzbek in Afghanistan • Uyghur, Kazakh and Kyrgyz in northwest China South Asia: • Urdu, Punjabi, Sindhi, Kashmiri, and Baluchi in Pakistan • Urdu and Kashmiri in India Southeast Asia: • Malay in Burma • Used for religious purposes in Malaysia, Indonesia, southern Thailand, Singapore, and the Philippines Africa: • Bedawi or Beja in Sudan • Hausa in Nigeria • Tamazight and other Berber languages 6 The name Mohamed is an excellent example. The name is literally written as M‐H‐M‐D. However, vowels and pronunciation depend on the region. D and T are interchangeable depending on the region, and the middle “M” is sometimes repeated when transcribed. -

The Ancient Mesopotamian Place Name “Meluḫḫa”

THE ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIAN PLACE NAME “meluḫḫa” Stephan Hillyer Levitt INTRODUCTION The location of the Ancient Mesopotamian place name “Meluḫḫa” has proved to be difficult to determine. Most modern scholars assume it to be the area we associate with Indus Valley Civilization, now including the so-called Kulli culture of mountainous southern Baluchistan. As far as a possible place at which Meluḫḫa might have begun with an approach from the west, Sutkagen-dor in the Dasht valley is probably as good a place as any to suggest (Possehl 1996: 136–138; for map see 134, fig. 1). Leemans argued that Meluḫḫa was an area beyond Magan, and was to be identified with the Sind and coastal regions of Western India, including probably Gujarat. Magan he identified first with southeast Arabia (Oman), but later with both the Arabian and Persian sides of the Gulf of Oman, thus including the southeast coast of Iran, the area now known as Makran (1960a: 9, 162, 164; 1960b: 29; 1968: 219, 224, 226). Hansman identifies Meluḫḫa, on the basis of references to products of Meluḫḫa being brought down from the mountains, as eastern Baluchistan in what is today Pakistan. There are no mountains in the Indus plain that in its southern extent is Sind. Eastern Baluchistan, on the other hand, is marked throughout its southern and central parts by trellised ridges that run parallel to the western edge of the Indus plain (1973: 559–560; see map [=fig. 1] facing 554). Thapar argues that it is unlikely that a single name would refer to the entire area of a civilization as varied and widespread as Indus Valley Civilization. -

Surnames in Europe

DOI: http://dx.doi.org./10.17651/ONOMAST.61.1.9 JUSTYNA B. WALKOWIAK Onomastica LXI/1, 2017 Uniwersytet im. Adama Mickiewicza w Poznaniu PL ISSN 0078-4648 [email protected] FUNCTION WORDS IN SURNAMES — “ALIEN BODIES” IN ANTHROPONYMY (WITH PARTICULAR REFERENCE TO POLAND) K e y w o r d s: multipart surnames, compound surnames, complex surnames, nobiliary particles, function words in surnames INTRODUCTION Surnames in Europe (and in those countries outside Europe whose surnaming patterns have been influenced by European traditions) are mostly conceptualised as single entities, genetically nominal or adjectival. Even if a person bears two or more surnames, they are treated on a par, which may be further emphasized by hyphenation, yielding the phenomenon known as double-barrelled (or even multi-barrelled) surnames. However, this single-entity approach, visible e.g. in official forms, is largely an oversimplification. This becomes more obvious when one remembers such household names as Ludwig van Beethoven, Alexander von Humboldt, Oscar de la Renta, or Olivia de Havilland. Contemporary surnames resulted from long and complicated historical processes. Consequently, certain surnames contain also function words — “alien bodies” in the realm of proper names, in a manner of speaking. Among these words one can distinguish: — prepositions, such as the Portuguese de; Swedish von, af; Dutch bij, onder, ten, ter, van; Italian d’, de, di; German von, zu, etc.; — articles, e.g. Dutch de, het, ’t; Italian l’, la, le, lo — they will interest us here only when used in combination with another category, such as prepositions; — combinations of prepositions and articles/conjunctions, or the contracted forms that evolved from such combinations, such as the Italian del, dello, del- la, dell’, dei, degli, delle; Dutch van de, van der, von der; German von und zu; Portuguese do, dos, da, das; — conjunctions, e.g. -

Introduction TOWARDS a THEORY of POLITICAL ONOMASTICS A

Introduction TOWARDS A THEORY OF POLITICAL ONOMASTICS A Personal Reflection Immigrants All those names mangled on Ellis Island … … … cut, stitched, and … remade as Mann … Carpenter or Leary. … Others, more secretive or radical, made up new names … (Carole Satyamurti in Satyamurti 2005: 25) June 30, 1992. (The morning after my mother died) They took away your name at the border Forsaking borders, You gave away your names. Rebecca Rivke not yours to give Bertha not yours to take Surnames middlenames Hungarianised Jewish names Yiddishised Hungarian names Unnamed renamed remained 2 • Names and Nunavut My mother who shall remain nameless would not name my children did not know her daughter’s name mis-naming me, un-named herself. Cruel and unusual punishment inflicted on daughters grandsons granddaughter … even the chosen ones injured by unreasoned distinction child after child after child abuses of body mind trust The cycle of trust begun again in sisters sisters’ children children’s hope. What was lost: mothering and motherlove acceptance and resolution kindness and peace What we have: names our own names our owned names love and hope and children. (Valerie Alia 1996: 77) Introduction: Towards a Theory of Political Onomastics • 3 As the child of European-Jewish (Ashkenazi) immigrants to North America, I grew up hearing naming stories. I knew I was named Valerie for a place called Valeria where my parents met, and Lee to commemorate a relative named Leah. I knew I was a giver as well as a receiver of names when, at age six, my parents invited me to help name my sister. -

Bramwell, Ellen S. (2012) Naming in Society: a Cross-Cultural Study of Five Communities in Scotland

Bramwell, Ellen S. (2012) Naming in society: a cross-cultural study of five communities in Scotland. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/3173/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ENGLISH LANGUAGE, COLLEGE OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW Naming in Society A cross-cultural study of five communities in Scotland Ellen Sage Bramwell September 2011 © Ellen S. Bramwell 2011 Abstract Personal names are a human universal, but systems of naming vary across cultures. While a person’s name identifies them immediately with a particular cultural background, this aspect of identity is rarely researched in a systematic way. This thesis examines naming patterns as a product of the society in which they are used. Personal names have been studied within separate disciplines, but to date there has been little intersection between them. This study marries approaches from anthropology and linguistic research to provide a more comprehensive approach to name-study. Specifically, this is a cross-cultural study of the naming practices of several diverse communities in Scotland, United Kingdom. -

Reference Guides for Registering Students with Non English Names

Getting It Right Reference Guides for Registering Students With Non-English Names Jason Greenberg Motamedi, Ph.D. Zafreen Jaffery, Ed.D. Allyson Hagen Education Northwest June 2016 U.S. Department of Education John B. King Jr., Secretary Institute of Education Sciences Ruth Neild, Deputy Director for Policy and Research Delegated Duties of the Director National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance Joy Lesnick, Acting Commissioner Amy Johnson, Action Editor OK-Choon Park, Project Officer REL 2016-158 The National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance (NCEE) conducts unbiased large-scale evaluations of education programs and practices supported by federal funds; provides research-based technical assistance to educators and policymakers; and supports the synthesis and the widespread dissemination of the results of research and evaluation throughout the United States. JUNE 2016 This project has been funded at least in part with federal funds from the U.S. Department of Education under contract number ED‐IES‐12‐C‐0003. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the U.S. Department of Education nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. REL Northwest, operated by Education Northwest, partners with practitioners and policymakers to strengthen data and research use. As one of 10 federally funded regional educational laboratories, we conduct research studies, provide training and technical assistance, and disseminate information. Our work focuses on regional challenges such as turning around low-performing schools, improving college and career readiness, and promoting equitable and excellent outcomes for all students. -

Last Name First Name/Middle Name Course Award Course 2 Award 2 Graduation

Last Name First Name/Middle Name Course Award Course 2 Award 2 Graduation A/L Krishnan Thiinash Bachelor of Information Technology March 2015 A/L Selvaraju Theeban Raju Bachelor of Commerce January 2015 A/P Balan Durgarani Bachelor of Commerce with Distinction March 2015 A/P Rajaram Koushalya Priya Bachelor of Commerce March 2015 Hiba Mohsin Mohammed Master of Health Leadership and Aal-Yaseen Hussein Management July 2015 Aamer Muhammad Master of Quality Management September 2015 Abbas Hanaa Safy Seyam Master of Business Administration with Distinction March 2015 Abbasi Muhammad Hamza Master of International Business March 2015 Abdallah AlMustafa Hussein Saad Elsayed Bachelor of Commerce March 2015 Abdallah Asma Samir Lutfi Master of Strategic Marketing September 2015 Abdallah Moh'd Jawdat Abdel Rahman Master of International Business July 2015 AbdelAaty Mosa Amany Abdelkader Saad Master of Media and Communications with Distinction March 2015 Abdel-Karim Mervat Graduate Diploma in TESOL July 2015 Abdelmalik Mark Maher Abdelmesseh Bachelor of Commerce March 2015 Master of Strategic Human Resource Abdelrahman Abdo Mohammed Talat Abdelziz Management September 2015 Graduate Certificate in Health and Abdel-Sayed Mario Physical Education July 2015 Sherif Ahmed Fathy AbdRabou Abdelmohsen Master of Strategic Marketing September 2015 Abdul Hakeem Siti Fatimah Binte Bachelor of Science January 2015 Abdul Haq Shaddad Yousef Ibrahim Master of Strategic Marketing March 2015 Abdul Rahman Al Jabier Bachelor of Engineering Honours Class II, Division 1 -

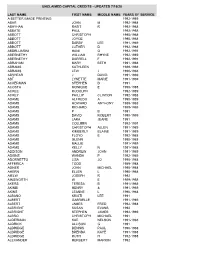

Last Name First Name Middle Name Years of Service A

UNCLAIMED CAPITAL CREDITS - UPDATED 7/16/20 LAST NAME FIRST NAME MIDDLE NAME YEARS OF SERVICE A BETTER IMAGE PRINTING 1992-1989 ABAR JOHN M 1992-1988 ABAYHAN RASIT R 1992-1988 ABBATE PAUL 1992-1988 ABBOTT CHRISTOPH 1990-1988 ABBOTT JOYCE 1990-1988 ABBOTT DARBY LEE 1991-1989 ABBOTT LUTHER D 1992-1988 ABDELUARIM HANI O 1992-1991 ABERNETHY WILLIAM RHYNE 1992-1989 ABERNETHY DARRELL F 1992-1991 ABRAHAM MARY BETH 1991-1988 ABRAMS KATHLEEN 1989-1988 ABRAMS LEW J 1990-1988 ABSHEAR J DAVID 1991-1989 ABT LYNETTE MARIE 1991-1989 ACKERMAN STEPHEN D 1991 ACOSTA MONIQUE E 1990-1988 ACREE RUDOLPH 1992-1989 ACREY PHILLIP CLINTON 1992-1988 ADAME ALFREDO A 1990-1989 ADAMS HOWARD ANTHONY 1989-1988 ADAMS RICHARD 1989-1988 ADAMS P B 1991 ADAMS DAVID ROBERT 1990-1989 ADAMS LARA JEANE 1991 ADAMS COLLEEN 1992-1991 ADAMS CHRISTOPH ALLEN 1991-1989 ADAMS KIMBERLY ELAINE 1991-1989 ADAMS FLOYD E 1992-1988 ADAMS GLENN 1990-1988 ADAMS MALLIE 1991-1989 ADAMS KELLY N 1991-1988 ADDISON ANDREW JOHN 1991-1989 ADKINS WANDA P 1992-1989 ADORNETTO LISA JO 1990-1988 AFFERICA TODD 1989-1988 AGNER JOHN MICHAEL 1990-1988 AHERN ELLEN L 1990-1988 AIELW JOSEPH R 1992 AINSWORTH W E 1989-1988 AKERS TERESA B 1991-1988 AKINBI HENRY & 1991-1989 AKINS LEANNE L 1990-1988 ALBANO KRISTI LEE 1991 ALBERT GABRIELLE 1991-1989 ALBERT JAMES FRED 1992-1988 ALBRIGHT SUSAN EVANS 1992 ALBRIGHT STEPHEN JAMES 1992-1989 ALBRO CHRISTOPH MICHAEL 1991 ALDERMAN KAE NELSON 1991-1988 ALDRICK ALLISON G 1991 ALDRIDGE DENNIS PAUL 1990-1988 ALDRIDGE BRENDA KAYE 1991-1988 ALDRIDGE RUTH H 1992-1988 ALEXANDER HERBERT -

Religious and Cultural Beliefs

Document Type: Unique Identifier: GUIDELINE CORP/GUID/027 Title: Version Number: Religious and Cultural Beliefs 4 Status: Ratified Target Audience: Divisional and Trust Wide Department: Patient Experience Author / Originator and Job Title: Risk Assessment: Rev Jonathan Sewell, Chaplaincy Team Leader in consultation Not Applicable with Chaplaincy colleagues and representatives of local faith communities Replaces: Description of amendments: Version 3 Religious and Cultural Beliefs Updated information CORP/GUID/027 Validated (Technical Approval) by: Validation Date: Which Principles Chaplaincy Department Meeting 26/05/2016 of the NHS Chaplaincy Team Meeting 23/06/16 Constitution Apply? 3 Ratified (Management Approval) by: Ratified Date: Issue Date: Patient and Carer Experience and 18/07/2016 18/07/2016 Involvement Committee Review dates and version numbers may alter if any significant Review Date: changes are made 01/06/2019 Blackpool Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust aims to design and implement services, policies and measures that meet the diverse needs of our service, population and workforce, ensuring that they are not placed at a disadvantage over others. The Equality Impact Assessment Tool is designed to help you consider the needs and assess the impact of your policy in the final Appendix. CONTENTS 1 Purpose ....................................................................................................................... 3 2 Target Audience ......................................................................................................... -

AACR2: Anglo-American Cataloguing Rules, 2Nd Ed. 2002 Revision

Cataloguing Code Comparison for the IFLA Meeting of Experts on an International Cataloguing Code July 2003 AACR2: Anglo-American Cataloguing Rules, 2nd ed. 2002 revision. - Ottawa : Canadian Library Association ; London : Chartered Institute of Library and Information Professionals ; Chicago : American Library Association, 2002. AAKP (Czech): Anglo-americká katalogizační pravidla. 1.české vydání. – Praha, Národní knihovna ČR, 2000-2002 (updates) [translated to Czech from Anglo-American Cataloguing Rules, 2nd ed. 2002 revision. - Ottawa : Canadian Library Association ; London : Chartered Institute of Library and Information Professionals ; Chicago : American Library Association, 2002. AFNOR: AFNOR cataloguing standards, 1986-1999 [When there is no answer under a question, the answer is yes] BAV: BIBLIOTECA APOSTOLICA VATICANA (BAV) Commissione per le catalogazioni AACR2 compliant cataloguing code KBARSM (Lithuania): Kompiuterinių bibliografinių ir autoritetinių įrašų sudarymo metodika = [Methods of Compilation of the Computer Bibliographic and Authority Records] / Lietuvos nacionalinė Martyno Mažvydo biblioteka. Bibliografijos ir knygotyros centras ; [parengė Liubovė Buckienė, Nijolė Marinskienė, Danutė Sipavičiūtė, Regina Varnienė]. – Vilnius : LNB BKC, 1998. – 132 p. – ISBN 9984 415 36 5 REMARK: The document presented above is not treated as a proper complex cataloguing code in Lithuania, but is used by all libraries of the country in their cataloguing practice as a substitute for Russian cataloguing rules that were replaced with IFLA documents for computerized cataloguing in 1991. KBSDB: Katalogiseringsregler og bibliografisk standard for danske biblioteker. – 2. udg.. – Ballerup: Dansk BiblioteksCenter, 1998 KSB (Sweden): Katalogiseringsregler för svenska bibliotek : svensk översättning och bearbetning av Anglo-American cataloguing rules, second edition, 1988 revision / utgiven av SAB:s kommitté för katalogisering och klassifikation. – 2nd ed. – Lund : Bibliotekstjänst, 1990. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/23/2021 09:14:00PM Via Free Access

russian history 44 (2017) 209-242 brill.com/ruhi What Do We Know about *Čьrnobogъ and *Bělъ Bogъ? Yaroslav Gorbachov Assistant Professor of Linguistics, Department of Linguistics, University of Chicago [email protected] Abstract As attested, the Slavic pantheon is rather well-populated. However, many of its nu- merous members are known only by their names mentioned in passing in one or two medieval documents. Among those barely attested Slavic deities, there are a few whose very existence may be doubted. This does not deter some scholars from articulating rather elaborate theories about Slavic mythology and cosmology. The article discusses two obscure Slavic deities, “Black God” and “White God,” and, in particular, reexamines the extant primary sources on them. It is argued that “Black God” worship was limited to the Slavic North-West, and “White God” never existed. Keywords Chernobog – Belbog – Belbuck – Tjarnaglófi – Vij – Slavic dualism Introduction A discussion of Slavic mythology and pantheons is always a difficult, risky, and thankless business. There is no dearth of gods to talk about. In the literature they are discussed with confidence and, at times, some bold conclusions about Slavic cosmology are made, based on the sheer fact of the existence of a par- ticular deity. In reality, however, many of the “known” Slavic gods are not much more than a bare theonym mentioned once or twice in what often is a late, un- reliable, or poorly interpretable document. The available evidence is undeni- ably scanty and the dots to be connected are spaced far apart. Naturally, many © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, 2017 | doi 10.1163/18763316-04402011Downloaded from Brill.com09/23/2021 09:14:00PM via free access <UN> 210 Gorbachov Slavic mythologists have succumbed to an understandable urge to supply the missing fragments by “reconstructing” them.