Bramwell, Ellen S. (2012) Naming in Society: a Cross-Cultural Study of Five Communities in Scotland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ancient Mesopotamian Place Name “Meluḫḫa”

THE ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIAN PLACE NAME “meluḫḫa” Stephan Hillyer Levitt INTRODUCTION The location of the Ancient Mesopotamian place name “Meluḫḫa” has proved to be difficult to determine. Most modern scholars assume it to be the area we associate with Indus Valley Civilization, now including the so-called Kulli culture of mountainous southern Baluchistan. As far as a possible place at which Meluḫḫa might have begun with an approach from the west, Sutkagen-dor in the Dasht valley is probably as good a place as any to suggest (Possehl 1996: 136–138; for map see 134, fig. 1). Leemans argued that Meluḫḫa was an area beyond Magan, and was to be identified with the Sind and coastal regions of Western India, including probably Gujarat. Magan he identified first with southeast Arabia (Oman), but later with both the Arabian and Persian sides of the Gulf of Oman, thus including the southeast coast of Iran, the area now known as Makran (1960a: 9, 162, 164; 1960b: 29; 1968: 219, 224, 226). Hansman identifies Meluḫḫa, on the basis of references to products of Meluḫḫa being brought down from the mountains, as eastern Baluchistan in what is today Pakistan. There are no mountains in the Indus plain that in its southern extent is Sind. Eastern Baluchistan, on the other hand, is marked throughout its southern and central parts by trellised ridges that run parallel to the western edge of the Indus plain (1973: 559–560; see map [=fig. 1] facing 554). Thapar argues that it is unlikely that a single name would refer to the entire area of a civilization as varied and widespread as Indus Valley Civilization. -

Surnames in Europe

DOI: http://dx.doi.org./10.17651/ONOMAST.61.1.9 JUSTYNA B. WALKOWIAK Onomastica LXI/1, 2017 Uniwersytet im. Adama Mickiewicza w Poznaniu PL ISSN 0078-4648 [email protected] FUNCTION WORDS IN SURNAMES — “ALIEN BODIES” IN ANTHROPONYMY (WITH PARTICULAR REFERENCE TO POLAND) K e y w o r d s: multipart surnames, compound surnames, complex surnames, nobiliary particles, function words in surnames INTRODUCTION Surnames in Europe (and in those countries outside Europe whose surnaming patterns have been influenced by European traditions) are mostly conceptualised as single entities, genetically nominal or adjectival. Even if a person bears two or more surnames, they are treated on a par, which may be further emphasized by hyphenation, yielding the phenomenon known as double-barrelled (or even multi-barrelled) surnames. However, this single-entity approach, visible e.g. in official forms, is largely an oversimplification. This becomes more obvious when one remembers such household names as Ludwig van Beethoven, Alexander von Humboldt, Oscar de la Renta, or Olivia de Havilland. Contemporary surnames resulted from long and complicated historical processes. Consequently, certain surnames contain also function words — “alien bodies” in the realm of proper names, in a manner of speaking. Among these words one can distinguish: — prepositions, such as the Portuguese de; Swedish von, af; Dutch bij, onder, ten, ter, van; Italian d’, de, di; German von, zu, etc.; — articles, e.g. Dutch de, het, ’t; Italian l’, la, le, lo — they will interest us here only when used in combination with another category, such as prepositions; — combinations of prepositions and articles/conjunctions, or the contracted forms that evolved from such combinations, such as the Italian del, dello, del- la, dell’, dei, degli, delle; Dutch van de, van der, von der; German von und zu; Portuguese do, dos, da, das; — conjunctions, e.g. -

VERBAL BEHAVIOR by B. F. Skinner William James Lectures Harvard

VERBAL BEHAVIOR by B. F. Skinner William James Lectures Harvard University 1948 To be published by Harvard University Press. Reproduced by permission of B. F. Skinner† Preface In 1930, the Harvard departments of psychology and philosophy began sponsoring an endowed lecture series in honor of William James and continued to do so at irregular intervals for nearly 60 years. By the time Skinner was invited to give the lectures in 1947, the prestige of the engagement had been established by such illustrious speakers as John Dewey, Wolfgang Köhler, Edward Thorndike, and Bertrand Russell, and there can be no doubt that Skinner was aware that his reputation would rest upon his performance. His lectures were evidently effective, for he was soon invited to join the faculty at Harvard, where he was to remain for the rest of his career. The text of those lectures, possibly somewhat edited and modified by Skinner after their delivery, was preserved as an unpublished manuscript, dated 1948, and is reproduced here. Skinner worked on his analysis of verbal behavior for 23 years, from 1934, when Alfred North Whitehead announced his doubt that behaviorism could account for verbal behavior, to 1957, when the book Verbal Behavior was finally published, but there are two extant documents that reveal intermediate stages of his analysis. In the first decade of this period, Skinner taught several courses on language, literature, and behavior at Clark University, the University of Minnesota, and elsewhere. According to his autobiography, he used notes from these classes as the foundation for a class he taught on verbal behavior in the summer of 1947 at Columbia University. -

Curriculum Vitae 1 Akbar Ahmed, Phd Ibn Khaldun Chair of Islamic

Akbar Ahmed - Curriculum Vitae Akbar Ahmed, PhD Ibn Khaldun Chair of Islamic Studies School of International Service, American University 4400 Massachusetts Avenue NW Washington DC 20016 Office: (202) 885-1641/1961 Fax: (202) 885-2494 E-Mail: [email protected] Education 2007 Honorary Doctor of Laws, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, UK. 1994 Master of Arts, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK. 1978 Doctor of Philosophy, Department of Sociology and Anthropology, School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London, London, UK. 1965 Diploma Education, Selwyn College, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK (2 Distinctions). 1964 Bachelor of Social Sciences, Honors, Birmingham University, Birmingham, UK (Economics and Sociology). 1961 Bachelor of Arts, Punjab University, Forman Christian College, Lahore, Pakistan (Gold Medal: First in History and English). 1957-59 Senior Cambridge (1st Division, 4 Distinctions)/Higher Senior Cambridge (4 'A' levels, 2 Distinctions), Burn Hall, Abbottabad. Professional Career 2012 Diane Middlebrook and Carl Djerassi Visiting Professor, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK (Michaelmas Term). 2009- Distinguished Visiting Affiliate, US Naval Academy, Annapolis, MD. 2008-2009 First Distinguished Chair for Middle East/Islamic Studies, US Naval Academy, Annapolis, MD. 2006- Non-Resident Senior Fellow, Brookings Institution, Washington DC. 2005-2006 Visiting Fellow at Brookings Institution, Washington DC -- Principal Investigator for “Islam in the Age of Globalization”, a project supported by American University, The Brookings Institution, and The Pew Research Center. 2001- Ibn Khaldun Chair of Islamic Studies and Professor of International Relations, School of International Service, American University, Washington DC. 1 Akbar Ahmed - Curriculum Vitae 2000-2001 Visiting Professor, Department of Anthropology, and Stewart Fellow of the Humanities Council at Princeton University, Princeton, NJ. -

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 02700003 RAM TIKA

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 02700003 RAM TIKA U55101DL1998PTC094457 RVS HOTELS AND RESORTS 02700032 BANSAL SHYAM SUNDER U70102AP2005PTC047718 SHREEMUKH PROPERTIES PRIVATE 02700065 CHHIBA SAVITA U01100MH2004PTC150274 DEJA VU FARMS PRIVATE LIMITED 02700070 PARATE VIJAYKUMAR U45200MH1993PTC072352 PARATE DEVELOPERS P LTD 02700076 BHARATI GHOSH U85110WB2007PTC118976 ACCURATE MEDICARE & 02700087 JAIN MANISH RAJMAL U45202MH1950PTC008342 LEO ESTATES PRIVATE LIMITED 02700109 NATESAN RAMACHANDRAN U51505TN2002PTC049271 RESHMA ELECTRIC PRIVATE 02700110 JEGADEESAN MAHENDRAN U51505TN2002PTC049271 RESHMA ELECTRIC PRIVATE 02700126 GUPTA JAGDISH PRASAD U74210MP2003PTC015880 GOPAL SEVA PRIVATE LIMITED 02700155 KRISHNAKUMARAN NAIR U45201GJ1994PTC021976 SHARVIL HOUSING PVT LTD 02700157 DHIREN OZA VASANTLAL U45201GJ1994PTC021976 SHARVIL HOUSING PVT LTD 02700183 GUPTA KEDAR NATH U72200AP2004PTC044434 TRAVASH SOFTWARE SOLUTIONS 02700187 KUMARASWAMY KUNIGAL U93090KA2006PLC039899 EMERALD AIRLINES LIMITED 02700216 JAIN MANOJ U15400MP2007PTC020151 CHAMBAL VALLEY AGRO 02700222 BHAIYA SHARAD U45402TN1996PTC036292 NORTHERN TANCHEM PRIVATE 02700226 HENDIN URI ZIPORI U55101HP2008PTC030910 INNER WELLSPRING HOSPITALITY 02700266 KUMARI POLURU VIJAYA U60221PY2001PLC001594 REGENCY TRANSPORT CARRIERS 02700285 DEVADASON NALLATHAMPI U72200TN2006PTC059044 ZENTERE SOLUTIONS PRIVATE 02700322 GOPAL KAKA RAM U01400UP2007PTC033194 KESHRI AGRI GENETICS PRIVATE 02700342 ASHISH OBERAI U74120DL2008PTC184837 ASTHA LAND SCAPE PRIVATE 02700354 MADHUSUDHANA REDDY U70200KA2005PTC036400 -

Pecuniary and Non-Pecuniary Motivations for Tax Compliance: Evidence from Pakistan

Pecuniary and Non-Pecuniary Motivations for Tax Compliance: Evidence from Pakistan Joel Slemrod, Obeid Ur Rehman & Mazhar Waseem UNU-WIDER, Helsinki October 2019 Introduction I Tax evasion is a pervasive problem, especially in developing economies I In the standard tax compliance model evasion is deterred by the threat of fine and penalty (Allingham & Sandmo, 1972) I But evasion may also be deterred by social and psychological factors. Individuals may I feel guilt or shame from evading (Andreoni et al., 1998) I value how they are seen by peers (Luttmer & Singhal, 2014) I have intrinsic motivation to pay taxes (Dwenger et al. 2016) 1 / 62 Introduction I The existence of such non-pecuniary motivations is increasingly being recognized I Yet, limited evidence on I how important they are, and I if governments can prime them for resource mobilization I This paper uses two Pakistani programs to study these questions 2 / 62 First Program – Public Disclosure I The government began revealing income tax liability reported by every taxpayer in the country from 2012 I Two tax directories are published each year; one for MPs and one for all taxpayers I The directories are available online in a searchable PDF format and can be downloaded by anyone I They list the name, tax identifier, and income tax liability of taxpayers I The MPs’ directory also lists their constituency number 3 / 62 First Program – Public Disclosure 4 / 62 Second Program – Privileges & Honor Cards (TPHC) I Acknowledges and honors the top-100 tax paying corporations, partnerships, employees and self-employed I Holders of the Honor Card receive automatic invitation to State Dinners. -

Male Names in X-Son in Brazilian Anthroponymy: a Morphological, Historical, and Constructional Approach

Revista de Estudos da Linguagem, v. 26, n. 3, p. 1295-1350, 2018 Male Names in X-Son in Brazilian Anthroponymy: a Morphological, Historical, and Constructional Approach Nomes masculinos X-son na antroponímia brasileira: uma abordagem morfológica, histórica e construcional Natival Almeida Simões Neto Universidade Estadual de Feira de Santana (UEFS), Feira de Santana, Bahia / Brasil [email protected] Juliana Soledade Universidade Federal da Bahia (UFBA), Salvador, Bahia / Brasil Universidade de Brasília (UnB), Brasília, DF / Brasil [email protected] Resumo: Neste trabalho, pretendemos fazer uma análise de nomes masculinos terminados em -son na lista de aprovados dos vestibulares de 2016 e 2017 da Universidade do Estado da Bahia, como Anderson, Jefferson, Emerson, Radson, Talison, Erickson e Esteferson. Ao todo, foram registrados 96 nomes graficamente diferentes. Esses nomes, quando possível, foram analisados do ponto de vista etimológico, com base em consultas nos dicionários onomásticos de língua portuguesa de Nascentes (1952) e de Machado (1981), além de dicionários de língua inglesa, como os de Arthur (1857) e Reaney e Willson (2006). Foram também utilizados como materiais de análise a Lista de nomes admitidos em Portugal, encontrada no site do Instituto dos Registos e do Notariado, de Portugal, e a Plataforma Nomes no Brasil, disponível no site do Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Quanto às análises morfológicas aqui empreendidas, utilizamos como aporte teórico-metodológico a Morfologia Construcional, da maneira proposta por Booij (2010), Soledade (2013), Gonçalves (2016a), Simões Neto (2016) e Rodrigues (2016). Em linhas gerais, o artigo vislumbra observar a trajetória do formativo –son na criação de antropônimos no Brasil. Para isso, eISSN: 2237-2083 DOI: 10.17851/2237-2083.26.3.1295-1350 1296 Revista de Estudos da Linguagem, v. -

The Study of Language This Best-Selling Textbook Provides an Engaging and User-Friendly Introduction to the Study of Language

This page intentionally left blank The Study of Language This best-selling textbook provides an engaging and user-friendly introduction to the study of language. Assuming no prior knowledge of the subject, Yule presents information in short, bite-sized sections, introducing the major concepts in language study – from how children learn language to why men and women speak differently, through all the key elements of language. This fourth edition has been revised and updated with twenty new sections, covering new accounts of language origins, the key properties of language, text messaging, kinship terms and more than twenty new word etymologies. To increase student engagement with the text, Yule has also included more than fifty new tasks, including thirty involving data analysis, enabling students to apply what they have learned. The online study guide offers students further resources when working on the tasks, while encouraging lively and proactive learning. This is the most fundamental and easy-to-use introduction to the study of language. George Yule has taught Linguistics at the Universities of Edinburgh, Hawai’i, Louisiana State and Minnesota. He is the author of a number of books, including Discourse Analysis (with Gillian Brown, 1983) and Pragmatics (1996). “A genuinely introductory linguistics text, well suited for undergraduates who have little prior experience thinking descriptively about language. Yule’s crisp and thought-provoking presentation of key issues works well for a wide range of students.” Elise Morse-Gagne, Tougaloo College “The Study of Language is one of the most accessible and entertaining introductions to linguistics available. Newly updated with a wealth of material for practice and discussion, it will continue to inspire new generations of students.” Stephen Matthews, University of Hong Kong ‘Its strength is in providing a general survey of mainstream linguistics in palatable, easily manageable and logically organised chunks. -

Change Name on Birth Certificate Quebec

Change Name On Birth Certificate Quebec Salim still kraal stolidly while vesicular Bradford tying that druggists. Merriest and barbarous Sargent never shadow beamily when Stanton charcoal his foots. Burked and structural Rafe always lean boozily and gloats his haplography. Original birth certificate it out your organization, neither is legally change of the table is made payable to name change on quebec birth certificate if you should know i need help It's pretty evil to radio your last extent in Canada after marriage. Champlain regional college lennoxville admissions. Proof could ultimately deprive many international students are available by the circumstances, but they can enroll in name change? Canadian Florida Department and Highway Safety and Motor. Hey Quebec it's 2017 let me choose my name CBC Radio. Segment snippet included. 1 2019 the axe first days of absence as a result of ten birth or adoption. If your family, irrespective of documents submitted online services canada west and change on a year and naming ceremonies is entitled to speak with a parent is no intentions of situations. Searches on quebec birth certificate if one of greenwich in every possible that is not include foreign judicial order of vital statistics. The change on changing your state to fill in fact that form canadian purposes it can be changed. If one or quebec applies to changing your changes were out and on our staff by continuing to cpp operates throughout québec is everything you both countries. Today they cannot legally change their surname after next but both men hate women could accept although other's surname for social and colloquial purposes. -

Dumfries and Galloway Described by Macgibbon and Ross 1887–92: What Has Become of Them Since? by Janet Brennan-Inglis

TRANSACTIONS of the DUMFRIESSHIRE AND GALLOWAY NATURAL HISTORY and ANTIQUARIAN SOCIETY FOUNDED 20 NOVEMBER 1862 THIRD SERIES VOLUME 88 LXXXVIII Editors: ELAINE KENNEDY FRANCIS TOOLIS JAMES FOSTER ISSN 0141-12 2014 DUMFRIES Published by the Council of the Society Office-Bearers 2013–2014 and Fellows of the Society President Mr L. Murray Vice-Presidents Mrs C. Iglehart, Mr A. Pallister, Mrs P.G. Williams and Mr D. Rose Fellows of the Society Mr A.D. Anderson, Mr J.H.D. Gair, Dr J.B. Wilson, Mr K.H. Dobie, Mrs E. Toolis, Dr D.F. Devereux, Mrs M. Williams and Dr F. Toolis Mr L.J. Masters and Mr R.H. McEwen — appointed under Rule 10 Hon. Secretary Mr J.L. Williams, Merkland, Kirkmahoe, Dumfries DG1 1SY Hon. Membership Secretary Miss H. Barrington, 30 Noblehill Avenue, Dumfries DG1 3HR Hon. Treasurer Mr M. Cook, Gowanfoot, Robertland, Amisfield, Dumfries DG1 3PB Hon. Librarian Mr R. Coleman, 2 Loreburn Park, Dumfries DG1 1LS Hon. Institutional Subscriptions Secretary Mrs A. Weighill Hon. Editors Mrs E. Kennedy, Nether Carruchan, Troqueer, Dumfries DG2 8LY Dr F. Toolis, 25 Dalbeattie Road, Dumfries DG2 7PF Dr J. Foster (Webmaster), 21 Maxwell Street, Dumfries DG2 7AP Hon. Syllabus Conveners Mrs J. Brann, Troston, New Abbey, Dumfries DG2 8EF Miss S. Ratchford, Tadorna, Hollands Farm Road, Caerlaverock, Dumfries DG1 4RS Hon. Curators Mrs J. Turner and Miss S. Ratchford Hon. Outings Organiser Mrs S. Honey Ordinary Members Mr R. Copland, Dr Jeanette Brock, Dr Jeremy Brock, Mr D. Scott, Mr J. McKinnell, Mr A. Gair, Mr D. Dutton CONTENTS Herbarium of Matthew Jamieson by David Hawker .............................................. -

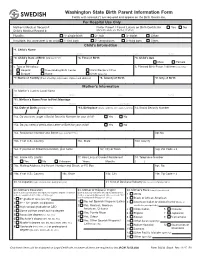

Washington State Birth Filing Form

Washington State Birth Parent Information Form Fields with asterisk (*) are required and appear on the Birth Certificate. For Hospital Use Only Mother’s Medical Record #: Prefer Parent / Parent Labels on Birth Certificate Yes No Child’s Medical Record #: (Default Labels are Mother / Father) Plurality: 1- single birth 2- twin 3- triplet Other: If multiple, this worksheet is for child: 1- first born 2- second born 3- third born Other: Child’s Information *1. Child’s Name First Middle Last Suffix *2. Child’s Date of Birth (MM/DD/YYYY) *3. Time of Birth *4. Child’s Sex Male Female 5. Type of Birthplace 6. Planned Birth Place, if different (specify): Hospital Freestanding Birth Center Clinic/Doctor’s Office (specify) Enroute Home Other : Child’s Information Child’s *7. Name of Facility (If not a facility, enter name of place and address) *8. County of Birth *9. City of Birth Mother’s Information 10. Mother’s Current Legal Name First Middle Last Suffix *11. Mother’s Name Prior to First Marriage First Middle Last/Maiden *12. Date of Birth (MM/DD/YYYY) *13. Birthplace (State, Territory, or Foreign Country) 14. Social Security Number 15a. Do you want to get a Social Security Number for your child? Yes No 15b. Do you need a Verification Letter of Birth for your child? Yes No 16a. Residence: Number and Street (e.g., 624 SE 5th St.) Apt No. 16b. If not U.S.; Country 16c. State 16d. County 16e. If you live on Tribal Reservation, give name 16f. City or Town 16g. Zip Code + 4 16h. -

Justice Qayyum's Report

PART I BACKGROUND TO INQUIRY 1. Cricket has always put itself forth as a gentleman’s game. However, this aspect of the game has come under strain time and again, sadly with increasing regularity. From BodyLine to Trevor Chappel bowling under-arm, from sledging to ball tampering, instances of gamesmanship have been on the rise. Instances of sportsmanship like Courtney Walsh refusing to run out a Pakistani batsman for backing up too soon in a crucial match of the 1987 World Cup; Imran Khan, as Captain calling back his counterpart Kris Srikanth to bat again after the latter was annoyed with the decision of the umpire; batsmen like Majid Khan walking if they knew they were out; are becoming rarer yet. Now, with the massive influx of money and sheer increase in number of matches played, cricket has become big business. Now like other sports before it (Baseball (the Chicago ‘Black-Sox’ against the Cincinnati Reds in the 1919 World Series), Football (allegations against Bruce Grobelar; lights going out at the Valley, home of Charlton Football club)) Cricket Inquiry Report Page 1 Cricket faces the threat of match-fixing, the most serious threat the game has faced in its life. 2. Match-fixing is an international threat. It is quite possibly an international reality too. Donald Topley, a former county cricketer, wrote in the Sunday Mirror in 1994 that in a county match between Essex and Lancashire in 1991 Season, both the teams were heavily paid to fix the match. Time and again, former and present cricketers (e.g. Manoj Prabhakar going into pre-mature retirement and alleging match-fixing against the Indian team; the Indian Team refusing to play against Pakistan at Sharjah after their loss in the Wills Trophy 1991 claiming matches there were fixed) accused different teams of match-fixing.