Rebbe Nachman and You

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Difference Between Blessing (Bracha) and Prayer (Tefilah)

1 The Difference between Blessing (bracha) and Prayer (tefilah) What is a Bracha? On the most basic level, a bracha is a means of recognizing the good that God has given to us. As the Talmud2 states, the entire world belongs to God, who created everything, and partaking in His creation without consent would be tantamount to stealing. When we acknowledge that our food comes from God – i.e. we say a bracha – God grants us permission to partake in the world's pleasures. This fulfills the purpose of existence: To recognize God and come close to Him. Once we have been satiated, we again bless God, expressing our appreciation for what He has given us.3 So, first and foremost, a bracha is a "please" and a "thank you" to the Creator for the sustenance and pleasure He has bestowed upon us. The Midrash4 relates that Abraham's tent was pitched in the middle of an intercity highway, and open on all four sides so that any traveler was welcome to a royal feast. Inevitably, at the end of the meal, the grateful guests would want to thank Abraham. "It's not me who you should be thanking," Abraham replied. "God provides our food and sustains us moment by moment. To Him we should give thanks!" Those who balked at the idea of thanking God were offered an alternative: Pay full price for the meal. Considering the high price for a fabulous meal in the desert, Abraham succeeded in inspiring even the skeptics to "give God a try." Source of All Blessing Yet the essence of a bracha goes beyond mere manners. -

Chassidus on the Chassidus on the Parsha +

LIGHTS OF OUR RIGHTEOUS TZADDIKIM בעזרת ה ' יתבר A Tzaddik, or righteous person , makes everyone else appear righteous before Hashem by advocating for them and finding their merits. Kedushas Levi, Parshas Noach (Bereishis 7:1) VA’ES CHA NAN _ CHASSIDUS ON THE PARSHA + Dvar Torah Deciphered Messages The Torah tells us ( Shemos 19:19) that when the Jewish people gathered at Mount Sinai to receive the Torah , “Moshe spoke and Hashem answered him with a voice.” The Gemora (Berochos 45a) der ives from this pasuk the principle that that an interpreter should not speak more loudly than the reader whose words he is translating. Tosafos immediately ask the obvious question: from that pasuk we see actually see the opposite: that the reader should n ot speak more loudly than the interpreter. We know, says Rav Levi Yitzchok, that Moshe’s nevua (prophecy) was different from that of the other nevi’im (prophets) in that “the Shechina was speaking through Moshe’s throat”. This means that the interpretation of the nevuos of the other nevi’im is not dependent on the comprehension of the people who hear it. The nevua arrives in this world in the mind of the novi and passes through the filter of his perspectives. The resulting message is the essence of the nevua. When Moshe prophesied, however, it was as if the Shechina spoke from his throat directly to all the people on their particular level of understanding. Consequently, his nevuos were directly accessible to all people. In this sense then, Moshe was the rea der of the nevua , and Hashem was the interpreter. -

Epic Tales by Rebbe Nachman of Breslev

Book of E p i c T a l e s (Sipurei Ma`asiyot) b y Rebbe Nachman of Breslev - Unabridged and With Appendices - hich we have been privileged to hear from the mouth of Rabbeinu W Hakadosh, the Hidden and Concealed Light, Nachal Nove`a Mekor Chokhmah/The Flowing Stream, The Wellspring of Wisdom [1] , HaRav Rabbi NACHMAN ztzuk"l of Breslev, grandson of the Ba`al Shem Tov Hakadosh and compiler of the books Likutei Moharan and several other compendiums. o out and see the might of your Master [2] Who has illuminated heavenly G Torah for us to enliven us as [sure as] it is this day[3 ] , for the everlasting world[4] ; and our God has not forsaken us in our servitude but has extended kindness to us[5] in each and every generation and has sent us deliverers and rabbis and tzadikei yesodei `olam/ righteous ones, foundation of the world [6] to teach us the way. His first [mercies] have come to pass[7] and yet His mercies have not ceased[8] at any period or any time. And He has performed kindness for us, drawing water from the wellsprings of salvation [9] , ancient things, words which are the secret of the world [10] , under wonderful and awesome clothings. See and understand and look at His wonderful and awesome way, which is an inheritance to us from our holy forefathers who were during ancient times in Yisrael. or such is the way of the upper holy ones [11] , harvesters of the field [12] , Fwho raised their hands and hearts to God, to clothe and conceal the King's treasure houses in story tales according to the generation and according to the times, -

Mattos Chassidus on the Massei ~ Mattos Chassidus on the Parsha +

LIGHTS OF OUR RIGHTEOUS TZADDIKIM בעזרת ה ' יתבר A Tzaddik, or righteous person , makes everyone else appear righteous before Hashem by advocating for them and finding their merits. Kedushas Levi, Parshas Noach (Bereishis 7:1) MATTOS ~ MASSEI _ CHASSIDUS ON THE PARSHA + Dvar Torah – Mattos Keep Your Word The Torah states (30:3), “If a man takes a vow or swears an oath to G -d to establish a prohibition upon himself, he shall not violate his word; he shall fulfill whatever comes out of his mouth.” In relation to this passuk , the Midrash quotes from Tehillim (144:4), “Our days are like a fleeting shadow.” What is the connection? This can be explained, says Rav Levi Yitzchok, according to a Gemara ( Nedarim 10b), which states, “It is forbidden to say, ‘ Lashem korban , for G-d − an offering.’ Instead a person must say, ‘ Korban Lashem , an offering for G -d.’ Why? Because he may die before he says the word korban , and then he will have said the holy Name in vain.” In this light, we can understand the Midrash. The Torah states that a person makes “a vow to G-d.” This i s the exact language that must be used, mentioning the vow first. Why? Because “our days are like a fleeting shadow,” and there is always the possibility that he may die before he finishes his vow and he will have uttered the Name in vain. n Story The wood chopper had come to Ryczywohl from the nearby village in which he lived, hoping to find some kind of employment. -

Rabbi Nachman of Breslev and Cognitive Therapy: a Short

2020-3882-AJSS Rabbi 1 Nachman of Breslev and Cognitive Therapy: A Short Comparison 2 of Conceptual and Psycho-Educational Similarities 3 4 The 5teachings of Rabbi Nachman of Breslev (1772-1810) focused on a number of key concepts 6 . He taught his followers that deviant past actions result from perceiving illusions 7 which contorted reality. In addition, these illusions which led in the past to transgressions 8 and deviant religious and social behavior, need to be rationally understood 9 in order to erase them. The individual needs to focus on the rational present 10 in order to improve his or her perceptions and actions and to live according to god 's11 will. Unlike classical depth psychology which dwells on problematic key personality 12 issues linked to the individual's past and are usually embedded in the subconscious 13 or the unconscious, cognitive therapy suggests that problematic issues affecting 14 the individual can be dealt with by helping the individual to rationally overcome 15 difficulties by identifying and changing dysfunctional thinking, beliefs, behavior, 16 and emotional responses. The conceptual definitions used by Rabbi Nachman 17 in his theological model expounded in the latter part of the eighteenth century 18 and by those espousing the model underlying cognitive therapy in the 20th and 21st 19centuries are remarkably similar and seem to have evolved from the same psychological 20 assumptions. The similarities between the principles underlying two theories 21 are analyzed and discussed in the present paper. 22 Keywords: 23 Chassidic (Piety) movement; Likutey Moharan; Tzaddik, (holy man); Rabbi 24 Nachman's guiding principles; Guiding principles of cognitive therapy 25 26 Introduction 27 28 29The Chassidic (Piety) movement was founded in the early 18th-century Eastern 30 Europe as a reaction against traditional Orthodox Judaism that traditionally 31 focused almost solely on legalistic and intellectual aspects of the Jewish 32 religion till that time. -

The Exalted Rebbe הצדיק הנשגב

THE EXALTED REBBE הצדיק הנשגב YESHUA IN LIGHT OF THE CHASSIDIC CONCEPTS OF DEVEKUT AND TZADDIKISM הקדמה לרעיון הדבקות בחסידות ויחסו למשיחיות ישוע THE EXALTED REBBE AN INTRODUCTION TO THE CONCEPT OF DEVEKUT AND TZADDIKISM IN CHASIDIC THOUGHT TOBY JANICKI Jewish critics of Messianic Judaism and the New Testament will often raise the argument that the Hebrew Scriptures do not set a precedent for the concept of an intercessor who stands between God and man. In other words, the idea that we need Messiah Yeshua to be the one to lead us to the Father and intercede on our behalf is not biblical. These critics state that we can approach God on our own faith and merit with no need for anyone to be a go-between. In their minds such an idea is idolatrous and completely foreign to Judaism. However, the talmudic sages of Israel developed the idea of the need for an intercessor in the con- cept of the tzaddik (“righteous one”). They, along with the later Chasidic movement, found proof for the need for an intermediary in the Torah and the rest of the Scriptures. By examining the tzaddik within Judaism we can not only defend our faith in the Master but we can also better understand His role from a Torah perspective. THE TZADDIK A true .(צדק ,is derived from the Hebrew word for “righteousness” (tzedek (צדיק) The word tzaddik tzaddik is a sinless person. Tzaddik has the sense of “one whose conduct is found to be beyond re- proach by the divine Judge.”1 According to the New Testament, there is no such person, “for all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God,”2 the only exception being Yeshua of Nazareth, who was “tempted in all things as we are, yet without sin.”3 From apostolic reckoning and the perspective of Messianic faith, Yeshua is the only true tzaddik. -

9 Sivan 1807.Dwd

SIVAN Life's splendor forever lies in wait 1 Sivan about each one of us in all its fullness, but veiled from view, deep down, Day Forty-five, making six weeks and three days, of the invisible, far off. It is there, though, Omer not hostile, not reluctant, not deaf. If Rosh Hodesh Sivan Hillula of Bohemian-born Austrian writer Franz Kafka, you summon it by the right word, by its pictured at right. Kafka was an admirer of right name, it will come. –Franz Kafka anarcho-communist theoretician Pyotr Kropotkin. As an elementary and secondary school student, Kafka wore a red carnation in his lapel to show his support for socialism. (1 Sivan 5684, 3 June 1924) Hillula of Polish-born U.S. labor lawyer Jack Zucker. When Senator Joseph McCarthy impugned Zucker’s patriotism, Zucker retorted, “I have more patriotism in my little finger than you have in your entire body!” (1 Sivan 5761, 23 May 2001) Hillula of Samaritan High Priest Levi ben Abisha ben Pinhas ben Yitzhaq, the first Samaritan High Priest to visit the United States (1 Sivan 5761, 23 May 2001) Hillula of U.S. labor leader Gus Tyler, pictured at right. Born Augustus Tilove, he adopted the sur- name Tyler as a way of honoring Wat Tyler, the leader of a 14th-century English peasant rebellion. (1 Sivan 5771, 3 June 2011) Hillula of Annette Dreyfus Benacerraf, niece of 1965 Nobel laureate in Physiology or Medicine Jacques Monod and wife of 1980 Nobel laureate in Physiology or Medicine Baruj Benacerraf (1 Sivan 5771, 3 June 2011) 2 Sivan Day Forty-six, making six weeks and four days, of the Omer Hillula of Rebbe Israel Hager of Vizhnitz, pictured at near right. -

THE TRUE TZADDIK Selected Thoughts from Rebbe Nachman of Breslov

HH cover: THE TRUE TZADDIK title page: THE TRUE TZADDIK Selected Thoughts from Rebbe Nachman of Breslov Published by Rabbi Yisroel Ber Odesser Jerusalem the Holy City 18 Tammuz 5752 TABLE OF CONTENTS Prologue....5 Introduction...7 1. The Concept of the Tzaddik...9 2. Who is the Tzaddik?.....23 3. Rosh Hashana with the Tzaddik....29 4. The Letter from the Tzaddik...35 5. The Gift from the Tzaddik -THE HOLY COVENANT...47 -THE TIKKUN HAKLALI...53 -PRAYER OF RABBI NATHAN...87 -PRAYERS TO GO TO UMAN....103 -THE TIKKUN CHATZOT....111 5 Prologue This book has been published through the collective effort of any individuals, in order to help the reader become acquainted with the concept of the Tzaddik. The price of this book is considered Tzeddakah (charity). In the merit of purchasing this book, may the owner be considered to have give a Pidyon (redemption money) to the True Tzaddik on behalf of the entire Jewish People. May it be Your will, O L-rd our G-d and G-d of our Fathers, to sweeten all the harsh and strict judgements against the entire Jewish People, through the supreme wonder, who acts with great loving- kindness and complete and simple mercy, without any trace of harsh judgment at all, Amen. 7 “And they [the children of Israel] believed in the L-rd and in Moses, His servant.” (Shemot 14:31) Rabbi Nathan of Nemirov, Rebbe Nachman's closest disciple, explains: “It's impossible to believe in G-d without the help of the Tzaddik of on one's generation.” [Four-fifth of the Hebrew people died in Egypt because they didn't believe in Moses' words. -

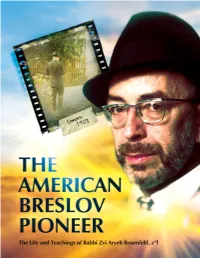

Rabbi-Rosenfeld-Bio-1.Pdf

The American Breslov Pioneer The Life and Teachings of Rabbi Zvi Aryeh Rosenfeld z”l (1922-1978) A modern-day pioneer who brought Breslov Chassidus to America and nurtured its growth for more than thirty years Published by BRESLOV RESEARCH INSTITUTE JERUSALEM/NY 2 / The American Breslov Pioneer COPYRIGHT ©2020 BRESLOV RESEARCH INSTITUTE ISBN: No part of this book may be translated, reproduced, stored in any retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. For further information: Breslov Research Institute POB 5370, Jerusalem, Israel 91053 or Breslov Research Institute POB 587, Monsey, NY 10952-0587 or Breslov Research Institute POB 11, Lakewood, NJ 08701 www.breslov.org e-mail: [email protected] PUBLISHER’S FOREWORD / 3 MAIN DEDICATION $10,000 YOUR DEDICATION TEXT HERE 4 / The American Breslov Pioneer FRONT PAGE BOOK DEDICATION $5,000 YOUR DEDICATION TEXT HERE PUBLISHER’S FOREWORD / 5 TABLE OF CONTENTS PUBLISHER’S FOREWORD .............................................................................................................. 4 PREFACE ....................................................................................................................................... 6 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................. 9 PROLOGUE ................................................................................................................................... -

Work at Not Needing Approval from Anyone and You Will

CHESHVAN “Work at not needing THEMES OF CHESVAN approval from anyone • Sifting through “the muck” • Putting faith in your efforts, and you will be free to believing they’ll blossom be who you really are.” • Following through on our intentions – Rebbe Nachman of Breslov1 • Grounding and breakthroughs 1. The homegirls At The Well would not put a teaching from a dude in our newsletter unless we knew he was a total righteous brother. Rebbe Nachman of Breslov is this guy. Known for merging the Jewish mystical elements with the ancient traditions in the Torah, the Rebbe invited us to speak to God as if we were talking to our best friend. So, in the spirit of this teaching, imagine if God really was just “one of us, on a bus, trying to make her way home.” 1 SPIRITUAL ENERGY OF CHESHVAN The cooler air and changing leaves inspire a natural turning ancestors returning from spiritual pilgrimages to visit their inwards right about now; the spirit of the Hebrew calendar Rebbes. Tishrei created the ultimate high, the moment of is in sync with this energy of introspection, but also some being closest to the Divine. When the pilgrimage was over spiritual hustle as well. The month of Cheshvan has a rolling and the people journeyed home, it was most likely a time up your sleeves and making good on all of last month’s hard of mourning and shock, a time of depression, or at least a spiritual work flavor to it. We just left Tishrei, the holiest little slumping, as they waded back into the “muck” of life. -

Succession in Contemporary Hasidism

1 Succession in Contemporary Hasidism Who Will Lead Us? ZADDIKIM OR REBBES When the modern Hasidic movement fi rst emerged in the late eight- eenth century, it was led mostly by charismatic men, commonly called zaddikim (loosely translated as the saintly or pious), who were them- selves the successors of ba’aley shem (wonder masters of the name of God or healers) and their counterparts, the maggidim (itinerant preach- ers).1 While the ba’aley shem were said to possess the mystical knowl- edge of Kabbalah that enabled them to invoke and in shaman-like fash- ion manipulate powerful, esoteric names of God in order to heal people, do battle with their demons, or liberate the human soul to unify itself with God, powers they used on behalf of those who believed in them, and while the maggidim were powerful preachers and magnetic orators who told tales and off ered parables or sermons that inspired their listen- ers, zaddikim had a combination of these qualities and more. With ba’aley shem they shared a knowledge of how to apply Kabbalah to the practical needs of their followers and to perform “miracles,” using their mystical powers ultimately to help their Hasidim (as these followers became known), and from the maggidim they took the power to inspire and attract with stories and teaching while inserting into these what their devotees took to be personal messages tailored just to them. With both, they shared the authority of charisma. Charisma, Max Weber explained, should be “applied to a certain quality of an individual personality by virtue of which he is set apart 1 HHeilmaneilman - WWhoho WillWill LeadLead Us.inddUs.indd 1 223/03/173/03/17 22:32:32 PPMM 2 | Succession in Contemporary Hasidism from ordinary men and treated as endowed with supernatural, superhu- man, or at least specifi cally exceptional powers or qualities.” 2 Whether the supernatural was an essential aspect of early Hasidism has been debated, but what is almost universally accepted is the idea that the men who became its leaders were viewed by their followers as extraordinary and exceptional. -

Tzadik Righteous One", Pl

Tzadik righteous one", pl. tzadikim [tsadi" , צדיק :Tzadik/Zadik/Sadiq [tsaˈdik] (Hebrew ,ṣadiqim) is a title in Judaism given to people considered righteous צדיקים [kimˈ such as Biblical figures and later spiritual masters. The root of the word ṣadiq, is ṣ-d- tzedek), which means "justice" or "righteousness". The feminine term for a צדק) q righteous person is tzadeikes/tzaddeket. Tzadik is also the root of the word tzedakah ('charity', literally 'righteousness'). The term tzadik "righteous", and its associated meanings, developed in Rabbinic thought from its Talmudic contrast with hasid ("pious" honorific), to its exploration in Ethical literature, and its esoteric spiritualisation in Kabbalah. Since the late 17th century, in Hasidic Judaism, the institution of the mystical tzadik as a divine channel assumed central importance, combining popularization of (hands- on) Jewish mysticism with social movement for the first time.[1] Adapting former Kabbalistic theosophical terminology, Hasidic thought internalised mystical Joseph interprets Pharaoh's Dream experience, emphasising deveikut attachment to its Rebbe leadership, who embody (Genesis 41:15–41). Of the Biblical and channel the Divine flow of blessing to the world.[2] figures in Judaism, Yosef is customarily called the Tzadik. Where the Patriarchs lived supernally as shepherds, the quality of righteousness contrasts most in Contents Joseph's holiness amidst foreign worldliness. In Kabbalah, Joseph Etymology embodies the Sephirah of Yesod, The nature of the Tzadik the lower descending