Katherina / Kate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shakespeare's Lost Playhouse

Shakespeare’s Lost Playhouse The playhouse at Newington Butts has long remained on the fringes of histories of Shakespeare’s career and of the golden age of the theatre with which his name is associated. A mile outside London, and relatively disused by the time Shakespeare began his career in the theatre, this playhouse has been easy to forget. Yet for eleven days in June, 1594, it was home to the two companies that would come to dominate the London theatres. Thanks to the ledgers of theatre entrepreneur Philip Henslowe, we have a record of this short venture. Shakespeare’s Lost Playhouse is an exploration of a brief moment in time when the focus of the theatrical world in England was on this small playhouse. To write this history, Laurie Johnson draws on archival studies, archaeology, en- vironmental studies, geography, social, political, and cultural studies, as well as methods developed within literary and theatre history to expand the scope of our understanding of the theatres, the rise of the playing business, and the formations of the playing companies. Laurie Johnson is Associate Professor of English and cultural studies at the University of Southern Queensland, current President of the Australian and New Zealand Shakespeare Association, and editorial board member with the journal Shakespeare. His publications include The Tain of Hamlet (2013), and the edited collections Embodied Cognition and Shakespeare’s Theatre: The Early Modern Body-Mind (with John Sutton and Evelyn Tribble, Routledge, 2014) and Rapt in Secret Studies: Emerging Shakespeares (with Darryl Chalk, 2010). Routledge Studies in Shakespeare For a full list of titles in this series, please visit www.routledge.com. -

Broadcasting the Arts: Opera on TV

Broadcasting the Arts: Opera on TV With onstage guests directors Brian Large and Jonathan Miller & former BBC Head of Music & Arts Humphrey Burton on Wednesday 30 April BFI Southbank’s annual Broadcasting the Arts strand will this year examine Opera on TV; featuring the talents of Maria Callas and Lesley Garrett, and titles such as Don Carlo at Covent Garden (BBC, 1985) and The Mikado (Thames/ENO, 1987), this season will show how television helped to democratise this art form, bringing Opera into homes across the UK and in the process increasing the public’s understanding and appreciation. In the past, television has covered opera in essentially four ways: the live and recorded outside broadcast of a pre-existing operatic production; the adaptation of well-known classical opera for remounting in the TV studio or on location; the very rare commission of operas specifically for television; and the immense contribution from a host of arts documentaries about the world of opera production and the operatic stars that are the motor of the industry. Examples of these different approaches which will be screened in the season range from the David Hockney-designed The Magic Flute (Southern TV/Glyndebourne, 1978) and Luchino Visconti’s stage direction of Don Carlo at Covent Garden (BBC, 1985) to Peter Brook’s critically acclaimed filmed version of The Tragedy of Carmen (Alby Films/CH4, 1983), Jonathan Miller’s The Mikado (Thames/ENO, 1987), starring Lesley Garret and Eric Idle, and ENO’s TV studio remounting of Handel’s Julius Caesar with Dame Janet Baker. Documentaries will round out the experience with a focus on the legendary Maria Callas, featuring rare archive material, and an episode of Monitor with John Schlesinger’s look at an Italian Opera Company (BBC, 1958). -

Actes Des Congrès De La Société Française Shakespeare, 30

Actes des congrès de la Société française Shakespeare 30 | 2013 Shakespeare et la mémoire Actes du congrès organisé par la Société Française Shakespeare les 22, 23 et 24 mars 2012 Christophe Hausermann (dir.) Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/shakespeare/1900 DOI : 10.4000/shakespeare.1900 ISSN : 2271-6424 Éditeur Société Française Shakespeare Édition imprimée Date de publication : 1 avril 2013 ISBN : 2-9521475-9-0 Référence électronique Christophe Hausermann (dir.), Actes des congrès de la Société française Shakespeare, 30 | 2013, « Shakespeare et la mémoire » [En ligne], mis en ligne le 13 avril 2013, consulté le 22 septembre 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/shakespeare/1900 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/shakespeare. 1900 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 22 septembre 2020. © SFS 1 SOMMAIRE Avant-Propos Gisèle Venet et Christophe Hausermann Christophe Hausermann (éd.) Foreword Gisèle Venet et Christophe Hausermann Christophe Hausermann (éd.) La mémoire et l’oubli dans les œuvres de Shakespeare Henri Suhamy Christophe Hausermann (éd.) Shakespeare and the fortunes of war and memory Andrew Hiscock Christophe Hausermann (éd.) Les enjeux de la mémoire dans The Conspiracy and Tragedy of Byron de George Chapman (1608) Gilles Bertheau Christophe Hausermann (éd.) The Memory of Hesione: Intertextuality and Social Amnesia in Troilus and Cressida Atsuhiko Hirota Christophe Hausermann (éd.) « The safe memorie of dead men » : réécriture nostalgique de l’héroïsme dans l’Angleterre de la première modernité -

J Ohn F. a Ndrews

J OHN F . A NDREWS OBE JOHN F. ANDREWS is an editor, educator, and cultural leader with wide experience as a writer, lecturer, consultant, and event producer. From 1974 to 1984 he enjoyed a decade as Director of Academic Programs at the FOLGER SHAKESPEARE LIBRARY. In that capacity he redesigned and augmented the scope and appeal of SHAKESPEARE QUARTERLY, supervised the Library’s book-publishing operation, and orchestrated a period of dynamic growth in the FOLGER INSTITUTE, a center for advanced studies in the Renaissance whose outreach he extended and whose consortium grew under his guidance from five co-sponsoring universities to twenty-two, with Duke, Georgetown, Johns Hopkins, North Carolina, North Carolina State, Penn, Penn State, Princeton, Rutgers, Virginia, and Yale among the additions. During his time at the Folger, Mr. Andrews also raised more than four million dollars in grant funds and helped organize and promote the library’s multifaceted eight- city touring exhibition, SHAKESPEARE: THE GLOBE AND THE WORLD, which opened in San Francisco in October 1979 and proceeded to popular engagements in Kansas City, Pittsburgh, Dallas, Atlanta, New York, Los Angeles, and Washington. Between 1979 and 1985 Mr. Andrews chaired America’s National Advisory Panel for THE SHAKESPEARE PLAYS, the BBC/TIME-LIFE TELEVISION canon. He then became one of the creative principals for THE SHAKESPEARE HOUR, a fifteen-week, five-play PBS recasting of the original series, with brief documentary segments in each installment to illuminate key themes; these one-hour programs aired in the spring of 1986 with Walter Matthau as host and Morgan Bank and NEH as primary sponsors. -

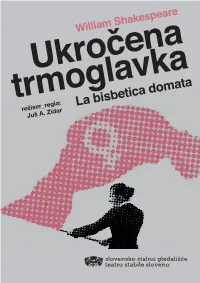

Gledališki List Uprizoritve

1 Na vest, da vam je boljše, so prišli z vedro komedijo vaši igralci; zdravniki so tako priporočili: preveč otožja rado skrkne kri, čemernost pa je pestunja blaznila. Zato da igra vam lahko le hasne; predajte se veselju; kratkočasje varje pred hudim in življenje daljša. William Shakespeare, UKROČENA TRMOGLAVKA 2 3 4 5 William Shakespeare Ukročena trmoglavka La bisbetica domata avtorji priredbe so ustvarjalci uprizoritve adattamento a cura della compagnia režiser/ regia: Juš A. Zidar prevajalec/ traduzione: Milan Jesih dramaturginja/ dramaturg: Eva Kraševec scenografinja/ scene:Petra Veber kostumografinja/ costumi:Mateja Fajt avtor glasbe/ musiche: Jurij Alič lektorica/ lettore: Tatjana Stanič asistent dramaturgije/ assistente dramaturg: Sandi Jesenik Igrajo/ Con: Iva Babić Tadej Pišek Zdravniki so tako priporočili: Vladimir Jurc Tina Gunzek preveč otožja rado skrkne kri, Jernej Čampelj Ilija Ota čemernost pa je pestunja blaznila. Andrej Rismondo Vodja predstave in rekviziterka/ Direttrice di scena e attrezzista Sonja Kerstein Lo raccomandano i medici: Tehnični vodja/ Direttore tecnico Peter Furlan Tonski mojster/ Fonico Diego Sedmak l’amarezza ha congelato Lučni mojster/ Elettricista Peter Korošic Odrski mojster/ Capo macchinista Giorgio Zahar il vostro sangue e la malinconia Odrski delavec/ Macchinista Marko Škabar, Dejan Mahne Kalin Garderoberka in šivilja/ Guardarobiera Silva Gregorčič è nutrice di follia. Prevajalka in prirejevalka nadnapisov/ Traduzione e adattamento sovratitoli Tanja Sternad Šepetalka in nadnapisi/ Suggeritrice e sovratitoli Neda Petrovič Premiera: 16. marca 2018/ Prima: 16 marzo 2018 Velika dvorana/ Sala principale 6 prvih del (okoli leta 1592) odločil, da bo obravnaval ravno t.i. žensko In živela sta srčno esej 01 vprašanje, odnos, ki so ga imeli moški do žensk v elizabetinski družbi, še posebno v pojmovanju inštitucije poroke. -

Shakespeare's

Shakespeare’s The Taming of the Shrew November 2014 These study materials are produced by Bob Jones University for use with the Classic Players production. AN EDUCATIONAL OUTREACH OF BOB JONES UNIVERSITY Philip Eoute as Petruchio and Annette Pait as Kate, Classic Players 2014 The Taming of the Shrew and Comic Tradition The Taming of the Shrew dates from the period of Shakespeare’s named Xantippa, who was Socrates’ wife and the traditional proto- early comedies, perhaps 1593 or 1594. In terms of the influences type of all literary shrews. The colloquy portrays her shrewishness as and sources that shaped the play, Shrew is a typical Elizabethan a defensive response to her husband’s bad character and behavior. comedy, a work that draws from multiple literary and folk traditions. Xantippa’s friend, an older wife named Eulalia, counsels her to Its lively, exuberant tone and expansive structure, for example, amend her own ways in an effort to reform her husband. In general, associate it with medieval English comedy like the mystery plays Shrew shows more kinship with such humanist works than with attributed to the Wakefield Master. the folktale tradition in which wives were, more often than not, beaten into submission. The main plot of Shrew—the story of a husband’s “taming” a shrewish wife—existed in many different oral and printed ver- Kate’s wit and facility with words also distinguish her from the sions in sixteenth-century England and Europe. Writings in the stock shrew from earlier literature. Shakespeare sketches her humanist tradition as well as hundreds of folktales about mastery character with a depth the typical shrew lacks. -

Partenope Director Biography

Partenope Director Biography Revival Director Roy Rallo began his career at Long Beach Opera, where he helped produce 15+ new productions, and directed Mozart’s Lucio Silla, Bartok’s Bluebeard’s Castle and Strauss’ Elektra. For San Francisco Opera Center, he directed La Finta Giardiniera, The Barber of Seville, Transformations and the Schwabacher Summer Concerts. For San Francisco Opera, he revived productions of The Barber of Seville and Pique Dame and has been a staff director for 23 seasons. Long-time collaboration with Christopher Alden includes co- directing Gluck’s rarely performed comedy L’Isle de Merlin for the Spoleto Festival USA, Verdi’s Aida for Deutsche Oper Berlin and Carmen for the National theater Mannheim. Rallo made his European directing debut with Der Rosenkavalier for Den Jyske Opera; a production that was nominated for Denmark’s prestigious Reumert Prize. In Germany, he directed a critically acclaimed production of Don Pasquale for the National theater and Staatskapelle Weimar; he returned to create an original music theater piece based on the lives of Germans who grew up in the rubble of WWII called Methusalem Projekt. In France, he directed a new production of Ariadne auf Naxos for Opéra National de Bordeaux. He recently directed a new production of Così fan tutte for Portland Opera, and is a founding member of Canada’s Le Chimera Project, whose debut production of Schubert’s Winterreise has toured Canada and France. A CD recording of the project, which arranged the piece for bass-baritone Philippe Sly and klezmer ensemble, will be released in March 2019 on Analekta. -

ANTA Theater and the Proposed Designation of the Related Landmark Site (Item No

Landmarks Preservation Commission August 6, 1985; Designation List 182 l.P-1309 ANTA THFATER (originally Guild Theater, noN Virginia Theater), 243-259 West 52nd Street, Manhattan. Built 1924-25; architects, Crane & Franzheim. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 1024, Lot 7. On June 14 and 15, 1982, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the ANTA Theater and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 5). The hearing was continued to October 19, 1982. Both hearings had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Eighty-three witnesses spoke in favor of designation. Two witnesses spoke in opposition to designation. The owner, with his representatives, appeared at the hearing, and indicated that he had not formulated an opinion regarding designation. The Commission has received many letters and other expressions of support in favor of this designation. DESCRIPTION AND ANALYSIS The ANTA Theater survives today as one of the historic theaters that symbolize American theater for both New York and the nation. Built in the 1924-25, the ANTA was constructed for the Theater Guild as a subscription playhouse, named the Guild Theater. The fourrling Guild members, including actors, playwrights, designers, attorneys and bankers, formed the Theater Guild to present high quality plays which they believed would be artistically superior to the current offerings of the commercial Broadway houses. More than just an auditorium, however, the Guild Theater was designed to be a theater resource center, with classrooms, studios, and a library. The theater also included the rrost up-to-date staging technology. -

American Music Research Center Journal

AMERICAN MUSIC RESEARCH CENTER JOURNAL Volume 19 2010 Paul Laird, Guest Co-editor Graham Wood, Guest Co-editor Thomas L. Riis, Editor-in-Chief American Music Research Center College of Music University of Colorado Boulder THE AMERICAN MUSIC RESEARCH CENTER Thomas L. Riis, Director Laurie J. Sampsel, Curator Eric J. Harbeson, Archivist Sister Mary Dominic Ray, O.P. (1913–1994), Founder Karl Kroeger, Archivist Emeritus William Kearns, Senior Fellow Daniel Sher, Dean, College of Music William S. Farley, Research Assistant, 2009–2010 K. Dawn Grapes, Research Assistant, 2009–2011 EDITORIAL BOARD C. F. Alan Cass Kip Lornell Susan Cook Portia Maultsby Robert R. Fink Tom C. Owens William Kearns Katherine Preston Karl Kroeger Jessica Sternfeld Paul Laird Joanne Swenson-Eldridge Victoria Lindsay Levine Graham Wood The American Music Research Center Journal is published annually. Subscription rate is $25.00 per issue ($28.00 outside the U.S. and Canada). Please address all inquiries to Lisa Bailey, American Music Research Center, 288 UCB, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO 80309-0288. E-mail: [email protected] The American Music Research Center website address is www.amrccolorado.org ISSN 1058-3572 © 2010 by the Board of Regents of the University of Colorado INFORMATION FOR AUTHORS The American Music Research Center Journal is dedicated to publishing articles of general interest about American music, particularly in subject areas relevant to its collections. We welcome submission of articles and pro- posals from the scholarly community, ranging from 3,000 to 10,000 words (excluding notes). All articles should be addressed to Thomas L. Riis, College of Music, University of Colorado Boulder, 301 UCB, Boulder, CO 80309-0301. -

"A Midsummer Night's Dream" at Eastman Thratre; Jan. 21

of the University of Rochester Walter Hendl, Director presents THE EASTMAN OPERA THEATRE's PRODUCTION of A MIDSUMMER NIGHT'S DREAM by Benjamin Britten Libretto adapted from William Shakespeare by Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears LEONARD TREASH, Director EDWIN McARTHUR, Conductor THOMAS STRUTHERS, Designer Friday Evening, January 21, 1972, at 8:15 Saturday Evening, January 22, 1972, at 8:15 CAST (in order of appearance) Friday, January 21 Saturday, January 22 Cobweb Robin Eaton Robin Eaton Pease blossom Candace Baranowski Candace Baranowski Mustardseed Janet Obermeyer Janet Obermeyer Moth Doreen DeFeis Doreen DeFeis Puck Larry Clark Larry Clark Oberon Letty Snethen Laura Angus Tytania Judith Dickison Sharon Harrison Lysander Booker T. Wilson Bruce Bell Hermia Mary Henderson Maria Floros Demetrius Ralph Griffin Joseph Bias Helena Cecile Saine Julianne Cross Quince James Courtney James Courtney Flute Carl Bickel David Bezona Snout Bruce Bell Edward Pierce Starveling Tonio DePaolo Tonie DePaolo Bottom Alexander Stephens Alexander Stephens Snug Dan Larson Dan Larson Theseus Fredric Griesinger Fredric Griesinger Hippolyta '"- Laura Angus Letty Snethen Fairy Chorus: Edwin Austin, Steven Bell, Mark Cohen, Thomas Johnson, William McNeice, Gregory Miller, John Miller, Swan Oey, Gary Pentiere, Jeffrey Regelman, James Singleton, Marc Slavny, Thomas Spittle, Jeffrey VanHall, Henry Warfield, Kevin Weston. (Members of the Eastman Childrens Chorus, Milford Fargo, Conductor) . ' ~ --· .. - THE STORY Midsummer Night's Dream, Its Sources, Its Construction, -

Contemporary Opera Studio Presents "Socrates", "Christopher Sly"

Contemporary Opera Studio presents "Socrates", "Christopher Sly" April 7, 1972 Contemporary Opera Studio, developed jointly by the San Diego Opera Company and the University of California, San Diego, will present a double-bill program of "Socrates" by Erik Satie and the comic "Christopher Sly" by Dominick Argento on Friday and Saturday, April 21 and 22. To be held in the recently opened UCSD Theatre, Bldg. 203 an the Matthews Campus, the two performances will begin at 8:30 p.m. Tickets are $2.00 for general admission and $1.00 for students. The Opera Studio was formed in the winter of 1971 to perform unusual works, and innovative productions of standard works, which, because of their unusual nature, could not be profitably performed by the main opera company. The developers of this experimental wing of the downtown opera company hope it will become a training school, emphasizing the theatrical aspects of opera, for young professional singers. The two operas to be performed make use of a wide range of acting techniques and musical effects demonstrated in acting and movement classes of the Opera Studio. "Socrates," written in 1918, is a "symphonic drama" based on texts translated from Plato's "Dialogues." The opera is unusual in that women take the roles of Socrates and his companions. Director of "Socrates" is Mary Fee. Double cast in the role of Socrates are Beverly Ogdon and Cathy Campbell. Erik Satie, composer of "Socrates", is was very much a part of the artistic life of Paris near the beginning of the 20th century. His friends included Debussy, Ravel, Cocteau, and Picasso. -

Braggart Courtship from Miles Gloriosus to the Taming of the Shrew

2707 Early Theatre 19.1 (2016), 81–112 http://dx.doi.org/10.12745/et.19.1.2707 Philip D. Collington ‘A Mad-Cap Ruffian and a Swearing Jack’: Braggart Courtship from Miles Gloriosus to The Taming of the Shrew There is a generic skeleton in Petruchio’s closet. By comparing his outlandish behav- iour in Shakespeare’s The Taming of the Shrew (ca 1592–94) to that of Pyrgopo- linices in Plautus’s Miles Gloriosus (ca 200 BC), as well to that of English variants of the type found in Udall, Lyly, and Peele, I re-situate Petruchio as a braggart soldier. I also reconstruct a largely forgotten comic subgenre, braggart courtship, with distinctive poetic styles, subsidiary characters, narrative events, and thematic func- tions. Katherina’s marriage to a stranger who boasts of his abilities and bullies social inferiors raises key questions: What were the comic contexts and cultural valences of a match between a braggart and a shrew? Is there a generic skeleton in Petruchio’s closet? When he arrives in Padua in The Taming of the Shrew (ca 1592–94), he introduces himself to locals as old Antonio’s heir — and those who remember the father instantly embrace the son. ‘I know him well’, declares Baptista, ‘You are welcome for his sake’ (2.1.67–9).1 But when Petruchio begins beating his servant and boasting of his abilities, he may also have struck playgoers as a character type they knew well: the braggart soldier. By comparing Petruchio to the type’s most storied ancestor, Pyrgopo- linices in Plautus’s Miles Gloriosus [The Braggard Captain] (ca 200 BC), as