Universi^ Miootlms International 300 N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Miles Poindexter Papers, 1897-1940

Miles Poindexter papers, 1897-1940 Overview of the Collection Creator Poindexter, Miles, 1868-1946 Title Miles Poindexter papers Dates 1897-1940 (inclusive) 1897 1940 Quantity 189.79 cubic feet (442 boxes ) Collection Number 3828 (Accession No. 3828-001) Summary Papers of a Superior Court Judge in Washington State, a Congressman, a United States Senator, and a United States Ambassador to Peru Repository University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections. Special Collections University of Washington Libraries Box 352900 Seattle, WA 98195-2900 Telephone: 206-543-1929 Fax: 206-543-1931 [email protected] Access Restrictions Open to all users. Languages English. Sponsor Funding for encoding this finding aid was partially provided through a grant awarded by the National Endowment for the Humanities Biographical Note Miles Poindexter, attorney, member of Congress from Washington State, and diplomat, was born in 1868 in Tennessee and grew up in Virginia. He attended Washington and Lee University (undergraduate and law school), receiving his law degree in 1891. He moved to Walla Walla, Washington, was admitted to the bar and began his law practice. He entered politics soon after his arrival and ran successfully for County Prosecutor as a Democrat in 1892. Poindexter moved to Spokane in 1897 where he continued the practice of law. He switched to the Republican Party in Spokane, where he received an appointment as deputy prosecuting attorney (1898-1904). In 1904 he was elected Superior Court Judge. Poindexter became identified with progressive causes and it was as a progressive Republican and a supporter of Theodore Roosevelt that he was elected to the House of Representatives in 1908 and to the Senate in 1910. -

Tax Reform in Oregon

Portland State University PDXScholar City Club of Portland Oregon Sustainable Community Digital Library 4-19-2002 Tax Reform in Oregon City Club of Portland (Portland, Or.) Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/oscdl_cityclub Part of the Urban Studies Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation City Club of Portland (Portland, Or.), "Tax Reform in Oregon" (2002). City Club of Portland. 507. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/oscdl_cityclub/507 This Report is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in City Club of Portland by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. The City Club of Portland Tax Reform Task Force Presents Its Report : TAX REFORM IN OREGON The City Club membership will vote on this report on Friday, April 19, 2002. Until the membership vote, the City Club of Portland does not have an official position on this report. The outcome of this vote will be reported in the City Club Bulletin dated May 3, 2002. The City Club of Portland Mission To inform its members and the community in public matters and to arouse in them a realization of the obligations of citizenship. Layout and design: Stephanie D. Stephens Printing: Ron Laster, Print Results Copyright (c) City Club of Portland, 2002. TAX REFORM IN OREGON EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Oregon's state and local tax system is precariously unbalanced, not well structured to assure sufficient revenue to meet costs of public services approved by law. -

Entering Theprogressive Fold

Chapter 20 Entering the Progressive Fold of a EMERGING as a national figure in 1910, Norris presented a picture stockily built man of medium stature with a mass of black hair flecked with grey and a closely clipped reddish brown mustache. His appear and to ance literally bespoke action. He walked briskly, talked tersely in a the point. His chin projected aggressively and his mouth shut the thin fine line. His left eyebrow drooped deceptively, a result of old hunting accident, but the sharpness of his eyes belied any impli cation of listlessness. He dressed simply, if not carelessly, usually in brown or black, and his coat generally fitted badly over a pair of muscular shoulders. a Norris gave the impression of energy personified. He had queer make. trick of pursing up his mouth to emphasize points he wished to However, in personal appearance he still looked like a country lawyer. him out Simple in tastes, quiet in dress, he had little to distinguish men. His wardly from other small-town business and professional favorite exercise was mowing the lawn and his favorite diversion was reading Dickens' novels. Whatever fame he had achieved was primarily the result of play almost odds. As a ing the parliamentary game against impossible to undermine boss rule in the House. master strategist, he had helped Since believers in good government were engaged in similar struggles served throughout the country, Norris and the insurgents conveniently could To a as a symbol of what a small intrepid group accomplish. believed that the generation of Americans most of whom problems and evils in American life were not of a fundamental nature, Norris cure in the and his fellow insurgents showed that the lay readjustment of the mechanisms. -

Student's Name

California State & Local Government In Crisis, 6th ed., by Walt Huber CHAPTER 6 QUIZ - © January 2006, Educational Textbook Company 1. Which of the following is NOT an official of California's plural executive? (p. 78) a. Attorney General b. Speaker of the Assembly c. Superintendent of Public Instruction d. Governor 2. Which of the following are requirements for a person seeking the office of governor? (p. 78) a. Qualified to vote b. California resident for 5 years c. Citizen of the United States d. All of the above 3. Which of the following is NOT a gubernatorial power? (p. 79) a. Real estate commissioner b. Legislative leader c. Commander-in-chief of state militia d. Cerimonial and political leader 4. What is the most important legislative weapon the governor has? (p. 81) a. Line item veto b. Full veto c. Pocket veto d. Final veto 5. What is required to override a governor's veto? (p. 81) a. Simple majority (51%). b. Simple majority in house, two-thirds vote in senate. c. Two-thirds vote in both houses. d. None of the above. 6. Who is considered the most important executive officer in California after the governor? (p. 83) a. Lieutenant Governor b. Attorney General c. Secretary of State d. State Controller 1 7. Who determines the policies of the Department of Education? (p. 84) a. Governor b. Superintendent of Public Instruction c. State Board of Education d. State Legislature 8. What is the five-member body that is responsible for the equal assessment of all property in California? (p. -

A Geophysical Study of the North Scappoose Creek, Alder Creek, Clatskanie River Lineament, Along the Trend of the Portland Hills Fault, Columbia County, Oregon

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1982 A geophysical study of the North Scappoose Creek, Alder Creek, Clatskanie River lineament, along the trend of the Portland Hills fault, Columbia County, Oregon Nina Haas Portland State University Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: http://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Geology Commons, and the Tectonics and Structure Commons Recommended Citation Haas, Nina, "A geophysical study of the North Scappoose Creek, Alder Creek, Clatskanie River lineament, along the trend of the Portland Hills fault, Columbia County, Oregon" (1982). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 3254. 10.15760/etd.3244 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Nina Haas for the Master of Science in Geology presented December 15, 1982. Title: A Geophysical Study of the North Scappoose Creek - Alder Creek - Clatskanie River Lineament, Along the Trend of the Portland Hills Fault, Columbia County, Oregon. APPROVED BY MEMBERS OF THE THESIS COMMITTEE: Chairman Giibett • Benson The Portland Hills fault forms a strong northwest trending lineament along the east side of the Tualatin Mountains. An en echelon lineament follows North Scappoose Creek, Alder Creek, and the Clatskanie River along the same trend, through Columbia County, Oregon. The possibility that this lineament follows a fault or fault zone was investigated in this study. Geophysical methods were used, with seismic 2 refraction, magnetic and gravity lines run perpendicular to the lineament. -

SUI JURIS - the TRUTH in the RECORD - Gaston

SUI JURIS - THE TRUTH IN THE RECORD - Gaston SUI JURIS THE TRUTH IN THE RECORD A PROCESS FOR THE PEOPLE TO ACCESS THE COURTS By Pamela and Will Gaston Especially see the Back Cover SUI JURIS TABLE OF CONTENTS A Process for The People to Access the Courts Chapter 1 Opening the Book ........................................................ Page 2 Chapter 2 Sui Juris = Sovereignty ................................................ Page 4 Chapter 3 As Any Reasonable Person Would Understand.......... Page 8 Chapter 4 Time to Claim Personal Sovereignty in Court ............ Page 9 Chapter 5 Already Heard It .......................................................... Page 13 Chapter 6 Introduction by Will Gaston ........................................ Page 15 Chapter 7 What Is Happening To You In The Courtroom.......... Page 18 Chapter 8 "Child Abuse Industry"; Non Constitutional Courts.. Page 19 Chapter 9 The Public Record - only Real thing happening .......... Page 23 Chapter 10 All Judges and Attorneys are Bar Members ............ Page 24 Chapter 11 Undisputed Testimony Becomes Fact ....................... Page 27 Chapter 12 Prosecute Your Own Case; Make the Record ......... Page 28 Chapter 13 File for Discovery - Freedom of Information Act ..... Page 29 Chapter 14 The Process for the People to Access the Courts ..... Page 30 Chapter 15 Make the Record - Insist on Speaking ..................... Page 37 Chapter 16 Going Into Court ......................................................... Page 38 Chapter 17 Filing Your Own Motions .......................................... -

BROKEN PROMISES: Continuing Federal Funding Shortfall for Native Americans

U.S. COMMISSION ON CIVIL RIGHTS BROKEN PROMISES: Continuing Federal Funding Shortfall for Native Americans BRIEFING REPORT U.S. COMMISSION ON CIVIL RIGHTS Washington, DC 20425 Official Business DECEMBER 2018 Penalty for Private Use $300 Visit us on the Web: www.usccr.gov U.S. COMMISSION ON CIVIL RIGHTS MEMBERS OF THE COMMISSION The U.S. Commission on Civil Rights is an independent, Catherine E. Lhamon, Chairperson bipartisan agency established by Congress in 1957. It is Patricia Timmons-Goodson, Vice Chairperson directed to: Debo P. Adegbile Gail L. Heriot • Investigate complaints alleging that citizens are Peter N. Kirsanow being deprived of their right to vote by reason of their David Kladney race, color, religion, sex, age, disability, or national Karen Narasaki origin, or by reason of fraudulent practices. Michael Yaki • Study and collect information relating to discrimination or a denial of equal protection of the laws under the Constitution Mauro Morales, Staff Director because of race, color, religion, sex, age, disability, or national origin, or in the administration of justice. • Appraise federal laws and policies with respect to U.S. Commission on Civil Rights discrimination or denial of equal protection of the laws 1331 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW because of race, color, religion, sex, age, disability, or Washington, DC 20425 national origin, or in the administration of justice. (202) 376-8128 voice • Serve as a national clearinghouse for information TTY Relay: 711 in respect to discrimination or denial of equal protection of the laws because of race, color, www.usccr.gov religion, sex, age, disability, or national origin. • Submit reports, findings, and recommendations to the President and Congress. -

Oregon's Civil

STACEY L. SMITH Oregon’s Civil War The Troubled Legacy of Emancipation in the Pacific Northwest WHERE DOES OREGON fit into the history of the U.S. Civil War? This is the question I struggled to answer as project historian for the Oregon Historical Society’s new exhibit — 2 Years, Month: Lincoln’s Legacy. The exhibit, which opened on April 2, 2014, brings together rare documents and artifacts from the Mark Family Collection, the Shapell Manuscript Founda- tion, and the collections of the Oregon Historical Society (OHS). Starting with Lincoln’s enactment of the final Emancipation Proclamation on January , 863, and ending with the U.S. House of Representatives’ approval of the Thirteenth Amendment abolishing slavery on January 3, 86, the exhibit recreates twenty-five critical months in the lives of Abraham Lincoln and the American nation. From the moment we began crafting the exhibit in the fall of 203, OHS Museum Director Brian J. Carter and I decided to highlight two intertwined themes: Lincoln’s controversial decision to emancipate southern slaves, and the efforts of African Americans (free and enslaved) to achieve freedom, equality, and justice. As we constructed an exhibit focused on the national crisis over slavery and African Americans’ freedom struggle, we also strove to stay true to OHS’s mission to preserve and interpret Oregon’s his- tory. Our challenge was to make Lincoln’s presidency, the abolition of slavery, and African Americans’ quest for citizenship rights relevant to Oregon and, in turn, to explore Oregon’s role in these cataclysmic national processes. This was at first a perplexing task. -

1 Chapter 1 California's People, Economy, and Politics

CHAPTER 1 CALIFORNIA'S PEOPLE, ECONOMY, AND POLITICS: YESTERDAY, TODAY, AND TOMORROW Like so much else about California, our state's politics appears to change constantly, unpredictably, and even inexplicably. Politicians seem to rise and fall more because of their personalities and campaign treasuries than because of their policies or political party ties. The governor and the legislature appear to be competing with one another rather than solving our problems. Multibillion-dollar campaigns ask voters to make decisions about issues that seem to emerge from nowhere only to see many overturned by the courts. Some Californians are confused or dis- illusioned by all of this and disdain politics and political participation. But however unpredictable or even disgusting California politics may appear, it is serious business that affects us all. And despite its volatility, California can be understood by examining its history and its present characteristics, especially its changing population and economy. Wave after wave of immigrants has made California a diverse, multicultural society , while new technologies have repeatedly transformed the state's economy. The resulting disparate ethnic and economic interests compete for the benefits and protections conferred by government thus shape the state's politics. But to understand California today-and tomorrow- we need to know a little about its past and about the development of these competing interests. COLONIZATION, REBELLION, AND STATEHOOD The first Californians were probably immigrants like the rest of us. Archaeologists believe that the ancestors of American Indians crossed 1 over the Bering Strait from Asia thousands of years ago and then headed south. By 1769, about three hundred thousand Native Americans were living mostly near the coast of what is now California, while the Spaniards were colonizing the area with missions and military outposts. -

Curtana: Sword of Mercy 7.1 (Summer 2020)

A Journal for the Study of the Military Chaplaincy Volume 7 Issue 1 (Summer 2020) Curtana † Sword of Mercy is published semiannually by Mere Inkling Press Seabeck, Washington Curtana † Sword of Mercy | i Introductory Comments An Introduction to the New Issue ......................................iii Principle Essays A Spiritual Journey of Life and Ministry .......................... 1 by Raul Sanchez War, Disfigurement and Christ .......................................... 9 by Mark Schreiber Chaplaincy Ministry During a Pandemic ........................ 27 by Naomi Paget The Art of Sharpening the Tool of Chaplaincy ............... 35 by Jim Browning Army Chaplains Serving in WWI A.E.F. Hospitals ........ 39 by Robert C. Stroud Editorials On Lessons Taught by Plagues ...................................... 117 by Diogenes the Cynic Martial Poetry Military Poetry from the Past to the Present ................ 121 ii | Curtana † Sword of Mercy Civil War Chaplain Biographies Recovered from a Variety of Historic Publications ...... 143 Eclectic Citations Passing References to Chaplains ................................... 167 Curtana † Sword of Mercy is published semiannually by Scriptorium Novum Press, LLC, ISSN 2150-5853. The purpose of the journal is to provide an independent forum for the preservation of military chaplaincy history and the discussion of issues of interest to those who care about military chaplaincy. Submissions and letters to the editor are welcome. Submissions are best preceded by an electronic query. The editorial office can be reached at [email protected]. All articles, editorials and other content of Curtana are copyrighted by their authors. Written permission is required for reproduction of any the contents except in the journal’s entirety (including this copyright notice). Curtana is not connected, in any way, to the United States Department of Defense, or any other governmental agency. -

![CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8733/chairmen-of-senate-standing-committees-table-5-3-1789-present-978733.webp)

CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present

CHAIRMEN OF SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–present INTRODUCTION The following is a list of chairmen of all standing Senate committees, as well as the chairmen of select and joint committees that were precursors to Senate committees. (Other special and select committees of the twentieth century appear in Table 5-4.) Current standing committees are highlighted in yellow. The names of chairmen were taken from the Congressional Directory from 1816–1991. Four standing committees were founded before 1816. They were the Joint Committee on ENROLLED BILLS (established 1789), the joint Committee on the LIBRARY (established 1806), the Committee to AUDIT AND CONTROL THE CONTINGENT EXPENSES OF THE SENATE (established 1807), and the Committee on ENGROSSED BILLS (established 1810). The names of the chairmen of these committees for the years before 1816 were taken from the Annals of Congress. This list also enumerates the dates of establishment and termination of each committee. These dates were taken from Walter Stubbs, Congressional Committees, 1789–1982: A Checklist (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1985). There were eleven committees for which the dates of existence listed in Congressional Committees, 1789–1982 did not match the dates the committees were listed in the Congressional Directory. The committees are: ENGROSSED BILLS, ENROLLED BILLS, EXAMINE THE SEVERAL BRANCHES OF THE CIVIL SERVICE, Joint Committee on the LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, LIBRARY, PENSIONS, PUBLIC BUILDINGS AND GROUNDS, RETRENCHMENT, REVOLUTIONARY CLAIMS, ROADS AND CANALS, and the Select Committee to Revise the RULES of the Senate. For these committees, the dates are listed according to Congressional Committees, 1789– 1982, with a note next to the dates detailing the discrepancy. -

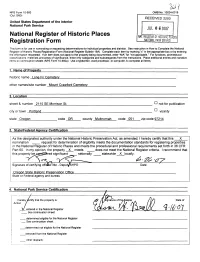

Vv Signature of Certifying Offidfel/Title - Deput/SHPO Date

NPSForm 10-900 OMBNo. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) RECEIVED 2280 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service JUL 0 6 2007 National Register of Historic Places m . REG!STi:ffililSfGRicTLA SES Registration Form NATIONAL PARK SERVICE — This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instruction in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classifications, materials and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name Lone Fir Cemetery other names/site number Mount Crawford Cemetery 2. Location street & number 2115 SE Morrison St. not for publication city or town Portland vicinity state Oregon code OR county Multnomah code 051 zip code 97214 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties | in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR [Part 60. In my opinion, the property _X_ meets __does not meet the National Register criteria.