1. Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

198J. M. Thornton Phd.Pdf

Kent Academic Repository Full text document (pdf) Citation for published version Thornton, Joanna Margaret (2015) Government Media Policy during the Falklands War. Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) thesis, University of Kent. DOI Link to record in KAR https://kar.kent.ac.uk/50411/ Document Version UNSPECIFIED Copyright & reuse Content in the Kent Academic Repository is made available for research purposes. Unless otherwise stated all content is protected by copyright and in the absence of an open licence (eg Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher, author or other copyright holder. Versions of research The version in the Kent Academic Repository may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check http://kar.kent.ac.uk for the status of the paper. Users should always cite the published version of record. Enquiries For any further enquiries regarding the licence status of this document, please contact: [email protected] If you believe this document infringes copyright then please contact the KAR admin team with the take-down information provided at http://kar.kent.ac.uk/contact.html Government Media Policy during the Falklands War A thesis presented by Joanna Margaret Thornton to the School of History, University of Kent In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History University of Kent Canterbury, Kent January 2015 ©Joanna Thornton All rights reserved 2015 Abstract This study addresses Government media policy throughout the Falklands War of 1982. It considers the effectiveness, and charts the development of, Falklands-related public relations’ policy by departments including, but not limited to, the Ministry of Defence (MoD). -

BBC MAG Spring 2018 32P A5 FC DS 90Gsm W + 4P 250Gsm Gloss

SOIRÉES MUSICALES Spring 2018 ~ Edition 58 Bramwell Tovey The Magazine of the BBC Concert Orchestra’s Supporters Club President: Richard Baker OBE Vice Presidents: Nigel Blomiley, Cynthia Fleming & Martin Loveday Editor / Chairman: Brian Crouch 57A Chilvers Bank, Baldock Herts. SG7 6HT Tel : 01462 892 670 Other Ed and Photos: Jenny Thomas Treasurer: James McLauchlan Accounts: Jenny Thomas Minute Secretary: James Connelly Membership Secretary: Jenny Thomas Tours & Visits: John Harding Website: Stephen Greenhalgh Constitution: Jan Mentha Orchestra Representative: Marcus Broome Soirées Musicales is the Magazine of the BBC Concert Orchestra's Supporters Club, which is an independent body set up in 1983 for the purpose of promoting and supporting the Members of the BBC Concert Orchestra. We are not affiliated to the BBC, neither do we receive any financial support from them. Disclaimer: The views expressed by the contributors to this Magazine are not necessarily the views of the Chairman, the Orchestra or the BBC. All material © 2018 BBC Concert Orchestra's Supporters Club ED LINES. The old saying tells us that absence makes the heart grow fonder but when absence is prolonged perhaps the fondness becomes somewhat diminished. I write this as a consequence of many phone calls in recent years regarding the scant appearances on Radio2 of the BBC Concert Orchestra. A few years ago, we had 2 or3 regular broadcasts every week by our favourite orchestra, but now it is just usually one a week and sometimes not even that. I know that they appear from time to time on Radio3, but not in my opinion playing the type of music which they do best or indeed the music for which they were originally intended. -

John's S John's John's

S John’s United Reformed Church Mar – Apr 2017 S John’s United Reformed ChurchRecord Somerset & Mowbray Roads, New Barnet, Herts, EN5 1RH From the Minister Contents S Faith Alone 2 Three New Church Members John‘Faith ’salone’, we trustU younited only Reformed 3 Easter Festival Church Jesus Christ, Emmanuel. Revised Common Lectionary One with us in our believing, you who know our natures well. 4 Chillin’ in Barbados When we’re tested, when we fail, 5 Fellowship Tea Dance by your faith we will prevail. 6 Calendar – March If people know only a little about the Reformation they may be familiar with the phrase: ‘Justification by faith’. But what does it mean and why did it come Time for Jesus to encapsulate the driving force of reform that convulsed Europe? The phrase is 7 Calendar – April taken from the Letter to the Romans 1:17, in which the Apostle Paul writes: “The righteousness of God is revealed in the gospel, beginning and ending in faith, as 8 Fellowship Talks the Scripture says: ‘Whoever is justified through faith shall gain life.’” The latter is a quotation from the Prophet Habakkuk (2:4). 9 Betty McKie Obituary The Saxon Augustinian Monk and Doctor of Sacred Theology, Martin Luther, 10 Charity Walk had in 1517 presented 95 Theses for debate and had, as a result, provoked a number of vigorous disputations about theology and the Church. In 1519 he continued to 11 Vienna Reformation Ball lecture on biblical books at the University of Wittenberg. When reflecting on the Letter to the Romans he was deeply troubled by one particular phrase: ‘the justice/ 12 Thank You righteousness of God’ (Justitia Dei). -

Cc Mr Whitmore NOTE for the RECORD Miss Stephens

• cc Mr Whitmore Miss Stephens----- NOTE FOR THE RECORD MEDIA I had a short meeting this afternoon with the Prime Minister on media activities (see attached minutes). The outcome is set out below. The Prime Minister: agreed in principle to sit for Mrs June Mendoza, of the Royal Society of Portrait Painters (but during the Summer Recess); - believes she should take a chance with requests from Peter Gill, Thames TV Eye, and Jane Corbin, the new Channel 4, for film profiles, subject to satisfactory control; the Gill programme is the more urgent but the Prime Minister is not prepared to consider making herself available for filming over a fortnight before the Budget; she would like me to minute her later on a suitable period including, Ouestions preparation, a regional visit, an international engagement - eg European Council - a constituency engagement and other events involving women, children, industrialists/entrepreneurs and the promotion of British enterprise and manufacturers; in relation to the last the Prime Minister mentioned Salts and Saltaire,manufacturers of woollen fabric; aims, so far as radio/tv is concerned, to appear or be heard being interviewed roughly every 3 weeks, taking account of the Budget; she agrees we should not enter into commitments until we know which way the land lies with the miners; agrees, in the light of the above, to give Thames TV Eye an interview at an early convenient date; and, to offer Brian Connell an interview for the Sunday Telegraph for early February, subject to confirmation and events; declines to give Roger Carroll, The Sun, an interview; would like to do a Panorama interview with Robin Day fairly soon but after Thames TV Eye; -2- has reservations about LWT Weekend World (Brian Walden) though this should be considered for September (if it is operating then) and Granada "World in Action"; asked me to prepare a presentional strategy paper for her early consideration; wants me to maintain the series of off the ITcord chats with editors; here we must consider Derek Jameson, News of the World; and Chris Ward, Daily Express. -

IWPR Training Manual SP.Qxp

reporting for change: a handbook for local journalists in crisis areas institute for war & peace reporting reporting for change: a handbook for local journalists in crisis areas institute for war & peace reporting THE INSTITUTE FOR WAR &PEACE REPORTING supports local media in areas of crisis and conflict. Programmes include reporting, training and institutional capacity-building projects. IWPR is an international network of non-profit organisations. IWPR - Europe, 48 Gray’s Inn Road, London WC1X 8LT IWPR (US), 1616 H Street, Washington, DC 20006 IWPR - Africa, P.O. Box 3317, Johannesburg 2121 www.iwpr.net Editing and contributions: Colin Bickler, Anthony Borden, Yigal Chazan, Alan Davis, Stephen Jukes, John MacLeod, Andrew Stroehlein, Stacy Sullivan, John Vultee, John West. Layout and design: Kate Smith. Cover photo: Panos. Inside photos: IWPR. 2004 © Institute for War & Peace Reporting ISBN Number: 1-902811-09-7 IWPR gratefully acknowledges the UK Department for International Development and other donors for support for this publication and for the many training and other media development programmes through which it was developed, including: Canadian International Development Agency Community Fund/National Lottery European Commisssion - EuropeAid Cooperation Office Ford Foundation Foreign and Commonwealth Office, UK McArthur Foundation Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Denmark Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Finland Ministry of Foreign Affairs, The Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Norway National Endowment for Democracy Open Society Institute The Sigrid Rausing Trust Swedish International Development Agency US Agency for International Development US State Department Dedicated to the thousands of local journalists around the world working in challenging and often dangerous situations to report freely from the frontlines of crisis and change Institute for War & Peace Reporting Contents Introduction 6 1. -

Annual Rental Rates Guide Look Back at 2012 Heavy Lift Cranes Large Truck Mounts December/January 2013Vol

C&A 14.9 P1-33:Layout 1 1/11/13 4:03 PM Page 1 www.vertikal.net www.vertikal.net December/January 2013 Vol. 14 issue 9 Annual rental rates guide Look back at 2012 Heavy lift cranes Large truck mounts ....TVH takes Mateco....Records broken in China....Genie’s big boom.... C&A 14.9 P1-33:Layout 1 1/11/13 4:03 PM Page 2 C&A 14.9 P1-33:Layout 1 1/11/13 4:04 PM Page 3 On the cover: A closer look at the 1,000 tonne Terex AC1000 which finally appeared at Bauma China after its initial announcement more than six years ago. & ccontentsa 17 Heavy lift cranes Comment 5 A Look Back News 6 at 2012 43 2012 has been another mixed year with the TVH acquires Mateco, Change of ownership for economic situation remaining fragile. However Ainscough, Big Genie on the way, Odewald buys in spite of this it seems most companies in our stake in Scholpp, Dick Schalekamp leaves Riwal, sector fared better than in 2011. Our annual Sky Aces announces the Fanlift, Huisman installs review looks back at the industry highlights record quayside crane, Sennebogen launches as well as the major news and events crawler crane, Dingli announces new UK from the world at large. distribution, New Bronto 60 metre truck mount, 25 Annual Rental Rate Guide Hiab launches loader crane, Ejar orders 10 Bauma China 53 Liebherr cranes, With interest growing in the Chinese market for Access Link joins construction equipment and more buyers in the Partnerlift, Big Effer West at least showing an interest in for Cuadrilla. -

British Journalism Review Tạp Chí Báo Chí Anh

British Journalism Review Tạp chí Báo chí Anh 2008 – 19:1 2008 – 19:1 Articles Các bài viết Investigative journalism Báo chí Điều tra David Leigh David Leigh Time to climb out of the sewer Thời điểm thoát khỏi nắp cống 5 5 Ivor Gaber Ivor Gaber The myth about Panorama Sự huyền bí về bức toàn cảnh 10 10 Roy Greenslade Roy Greenslade People power Sức mạnh con người 15 15 Joseph Harker Joseph Harker Ethnic balance: race against the tide Cân bằng sắc tộc: chủng tộc chống lại thủy triều 23 23 Chris Moss Chris Moss Travel journalism: the road to nowhere Báo chí du lịch: co đường tới hư vô 33 33 Bill Hagerty Bill Hagerty Tony Hall: fighter pilot, enter stage left Tony Hall: phi công chiến đấu, bước vào bên 41 trái sân khấu 41 Kevin Sutcliffe Kevin Sutcliffe Not guilty - but who�s to know? Không phạm tội – nhưng ai biết đây? 48 48 Tom Whitwell Tom Whitwell Con voi độc: sửa lại không gian ảo 57 Rogue elephant: editing in cyberspace 57 Lauren Bravo Lauren Bravo Qũy mặc áo cà sa The devil wears Primark 63 63 John Knight John Knight Sự kết thúc của những lời tạm biệt dài Last of the long goodbyes 69 69 The Cudlipp Award Giải thưởng Cudlipp 74 74 BOOK REVIEWS CÁC PHÊ BÌNH SÁCH Gus Macdonald on World in Action Gus Macdonald về Thế giới hành động 81 81 Joy Johnson on Reporting Iraq Joy Johnson về Báo cáo Iraq 77 77 Don Berry on Guardian Style Don Berry về Phong cách người bảo trợ 79 79 Julia Langdon on Katharine Whitehorn Julia Langdon về Katharine Whitehorn 81 81 Jon Snow on Channel 4 Jon Snow về Kênh 14 83 83 Michael Leapman on Christina Lamb Michael Leapman về Christina Lamb 85 85 Anthony Delano on media moguls Anthony Delano về những người có thể lực 87 truyền thông. -

Part Iii: Television Ne\Vswortiiiness and Proi)Tjction Cultuire

I PART III: TELEVISION NE\VSWORTIIINESS AND PROI)TJCTION CULTUIRE: NEWS ORGAMSATION AND NEWS PROGRAMME SIMILARITIES AND DIFFERENCES Part ifi of this thesis comprises three parts. Chapter 6 provides a detailed analysis of the similarities in news content and news production exhibited by different television programmes and Chapter 7 provides an analysis of the differences in content and production shown by those same news programmes. Chapter 8 is a detailed case study of television news coverage of the ending and aftermath of the Waco siege in Texas, USA in April 1993. The analysis in Part 111 draws upon the research data from Part II and the theoretical insights in Part I A central concern of Part ifi of this thesis is the role of the mass media in their potential public interest capacity. I have argued earlier that television news should make a contribution to the welfare of society and has a social responsibility to provide news which has useful informational content. Such a role is vital if the television news organisations are to fulfil their remit as institutions which embody citizenship and which aim to empower citizens to act more competently in the public sphere. In Chapters 6, 7 and 8 and in the Concluding chapter, I closely examine and assess whether the television news media can fulfil such a role in Britain in the 1990s. 36? First, in Chapter 6 we turn to the similarities inherent in television news production, selection and content output which also helps us to assess the broad cultural and professional values and norms present in all teleyision newsrooms. -

(E.Jameson) 16;10 1995 Garden Party, the 27

240 Years Of Bliss 21;5-7 Alberti, Leon Battista 40;3 American Maverick Architecture I Arch, Gothick, Dogmersfield Park, 1000 Curiosities of Britain (E.Jameson) Albury Park SR 40;3 55;3 Odiham HA 17;10 16;10 Albury SR, Indian summerhouse 24;16 American Maverick Architecture II Arch, Gubbins (Gobions), Brookman’s 1995 Garden Party, The 27;10 25;13 56,10 Park HE 12;15 Alcester HW, Cookhill Priory, gazebo Amersfoort (NL) 4;2 Arch, Hunmanby, Rudston HU 57;12 A 17;17 Amesbury WI, Chinese House 5;15 Arch, Lydford DV 18;4 Alcock, Dr Nat 9;6 13;5 14;15 33;15 Arch, Meath Gardens LO E2 41;4 A272: An Ode to a Road (P.Boogaart) Alcove Seat, Croome Court HW 2;6 Amherst, Alicia 2;8 Arch, Middleton SU 13;13 45;15 Alcove seat, Dogmersfield Park, Odiham Amherst, Sir Jeffery 58;4 Arch, rusticated, Hartwell House BU A La Ronde, Exmouth DV 7;15 11;7 HA 17;10 Amir al-Ghazzi, Abdul 14;13 11;9 22;10-11 Alcove, The, Brympton d’Evercy, Yeovil Ammanati, Bartolomeo 59;13 Arch, Thurso Castle YHI 5;14 A La Ronde: Of Myths And Men 22;10- SO 14;13 Ammerdown Park, Kilmersdon SO 16;15 Arch, Torpoint CO 55;11 11 Alcove, The, Hagley Park HW, 17;20 Ammersdown Park AV 32;20 Arch, triumphal, Werrington Park CO A.A.A.A.A.A.A. 16;17 Alden Biesen (B), folly group 4;3 Amnesty International 21;8 55;9 Aall, Sally, Port Royal Foundation 10;12 Alderley Edge CH, beacon 30;3,4 Amphitheatre, Werrington Park CO Arch, Valletta (M) 18;8 Abberley Clock Tower HW 47;11 Alderley GL, Banqueting House 45;16 55;9 Arch, Westwick House NF 57,7 Abbey Craig YCE 3;11 Alderley GL, summerhouse 35;4 36;6 -

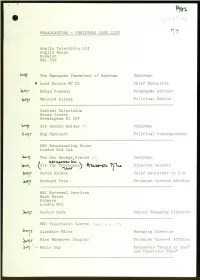

Kuoci-In Director General David Holmes� Chief Assistant to D/G

BROADCAS ING - CHRISTMAS CARD LIST Anglia Television Ltd Anglia House Norwich NR1 3JG The Marquess Townshend of Raynham Chairman * Lord Buxton MC DL Chief Executive -64-r- Brian Connell Programme Adviser Malcolm Allsop Political Editor Central Television Broad Street Birmingham Bl 2JP 1,11 Sir Gordon Hobday Chairman Reg Harcourt Political Correspondent BBC Broadcasting House London W1A IAA The Hon George Howard Chairman 10'r tanrtaVu.t (Sir Ian Trethowar) kuoci-iN Director General David Holmes Chief Assistant to D/G Bernard Tate Producer Current Affairs BBC External Services Bush House Aldwych London WC2 Austen Kark De,outy Managing Director BBC Television Contre Alasdair Milne M,,,,-nging Director ;:iss Margaret Dougla'.= Producer Current Affairs 4-1") Robin Day Presenter "World at One" aud "Question Time" • Border Television Television Centre Carlisle CA1 3NT 4.117 Professor Esmond Wright Chairman 1411 Sir John Burgess OBE TD DL JP Vice Chairman 1 James Bredin Managing Director Grampian Television Queen's Cross Aberdeen AB9 2XJ TT Cabtain lain Tennant JP Chairman Granada Television 36 Golden Square London W1R 4AH )3411 Alex Bernstein Deputy Chairman 104-41-1Sir Denis Forman OBE Chairman 14-r\1David Plowright Joint M/D 1411 Donald Harker Director of Public Affairs 1 Barrie Heads M/D Granada Intn'l HTV Wales Television Centre Cardiff CF1 9XL The Rt Hon Lord Harlech KCMG Chairman IBA 70 Brombton Road London SW3 lEY Lord Thomson of Monifieth Chalrman Sir Brian Yours,' Director General 1)7 David Glencross ITN News Ltd ITN House 48 Wells -

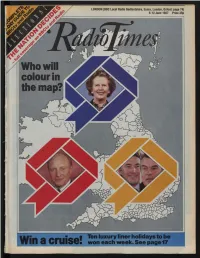

1987-Pages.Pdf

oimes 35 Marylebone High Street. London W1M 4AA Tel 01-580 5577 Published by Journals Division of BBC Enterprises Ltd Vol 253 No 3315 BBC Enterprises Ltd 1987 Editor Brian Gearing Deputy � Art Editor Brian Thomas Programme Editor Hugo Martin Features Editor Veronica Hitchcock Planning Editor Francesca Serpell ELECTION87 4 TheBattleground PeterSnow's 102 vital seats 6 First Results Who'llbe first past the polls? 8 HungParliaments AnthonyKing asks if they 're good for'What matters is the night' the constitution Anthony King, P 8 SHORTLY BEFORE 8.0 one Thursday evening have hitches: what matters is the night.' Tait is 10 Out of the House in April, some 150 employees put their clocks enthusiastic about the technology at his team's MPs ^gst who'IImiss forward by three hours and pretended it was 11 disposal: 'We're introducing some of the most tne jt^^^t^ Commonstouch June. BBCtv and Radio's full-scale General advanced equipment available - elections are 11 Carrott Election rehearsal was under way. ideally suited for computer animation.' ^^^^H� Jasper plays party games Of course, the results being processed by The names of every single candidate have ^^^H massed ranks of VDU weren't been in the General Election since 12 Grand Prix operators real; computer ^^^^Hf when returning officers read out voting figures, nominations closed on 27 May, and every result, ^^^^^m competition and successful candidates made grateful once declared, will be instantly available not 13 The Secret File speeches or gave triumphant interviews, all only to BBCtv and Radio studios but also to on Citizen K parts were in fact played by BBC reporters and everyone with a teletext set. -

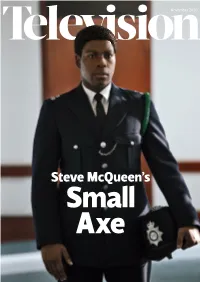

Steve Mcqueen's

November 2020 Steve McQueen’s Small Axe The world is made up of Innovators and Storytellers, Change-makers, Healers and Wanderers. Our artists create music that is as unique as they are, to soundtrack a world of stories and content. MAKE A MARK THROUGH MUSIC AND USE IT TO TELL YOUR STORY AUDIONETWORK.COM/DISCOVER/ART-OF-THE-ARTIST SEND US YOUR BRIEF [email protected] Journal of The Royal Television Society November 2020 l Volume 57/10 From the CEO The nights are drawing even the most inhospitable places We report on two excellent events in and opportunities look tempting and his empathy in the ongoing RTS Digital Convention for socialising are, to towards those he meets shines 2020. The first featured ITV’s CEO, put it mildly, limited. through the screen. Matthew Bell’s Carolyn McCall. The second saw two What better time to Comfort Classic celebrates his epic leading surgeons, Dr Alan Karthikesa watch some standout Pole to Pole trek, first shown in 1992. lingam and Professor Lord Darzi, dis shows? Few figures in lockdown have been cuss the potential impact of artificial This month’s cover story is Small as inspirational as Captain Tom Moore, intelligence in healthcare. Axe, Steve McQueen’s series of films now Captain Sir Tom Moore. We share Finally, I’m proud to announce looking at the experience of London’s how ITV News Anglia reporter Rebecca 40 new RTS bursary scholars. We aim West Indian community in the second Haworth broke the story of his heroic to widen participation in, and access half of the 20th century.