Nanaimo Harbour: Past, Present, and Future John Dunham Address To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DROUGHT UPDATE >

DROUGHT UPDATE > PULLOUT INSIDE WATER REGION 6 StreamsState 2015 WATER QUALITY EDITION Haslam Creek This publication gives a snapshot of two streams in your local water region that have been monitored for the past three years as part of the Community Watershed Monitoring Network. Made possible with community partners including provincial and local government, private forest companies, environmental stewardship organizations and volunteers, this network is coordinated through the RDN’s Drinking Water and Watershed Protection (DWWP) Program to monitor water quality in 23 streams across the region. We are excited to share what we continue to learn about our local water as we work to achieve goals outlined in the DWWP Action Plan. For more information please visit: www.dwwp.ca The Community Watershed Program 2 under the Drinking Water and Watershed Protection Action Plan outlines the goal to improve information about the Monitoring region’s water resources in terms of quantity and quality. The Community Watershed Monitoring Network (CWMN) furthers this program action by collecting water quality data to track Network stream health. Partnership between local stewardship groups, BC Ministry of Environment, Island Timberlands and the RDN DWWP program enables the expansion of monitoring in our region. Volunteers sample water quality in 17 watersheds at 51 sites. Monitoring occurs: – 5 consecutive weeks Aug. to Sept. (summer low flow) – 5 consecutive weeks Oct. to Nov. (fall flush period) suspended particles in water; linked to higher levels of contaminants water quality indicators oxygen dissolved in water supports aquatic life affects processes in water and in aquatic life This DWWP program is linked to Indicator 5 of our Regional Growth Strategy (RGS) monitoring program which measures progress towards achieving Goal 2 of the RGS: to “protect and enhance the environment and minimize ecological damage related to growth and development”. -

Nanaimo Harbour & Gabriola Island Terminal Development Planning

Nanaimo Harbour & Gabriola Island Terminal Development Planning PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT SUMMARY JUNE 2018 YOUR INPUT IS IMPORTANT TO US AND WILL HELP SHAPE OUR FUTURE PLANS. ENGAGEMENT HIGHLIGHTS In January 2018, BC Ferries launched the Terminal The May engagement events focused on: Development planning process for the Nanaimo Harbour and Gabriola Island terminals – a HOW the community gets to and from the planning initiative that will result in the phased terminals implementation of strategies, actions and projects over a 25 year horizon. Terminal Development WHY the terminal is important to the Plans will help BC Ferries develop terminals in a Terminal Development community cost effective, organized, phased and efficient way. Plans will enable BC Ferries challenges does the community face to develop terminals in a WHAT cost effective, organized, today when using BC Ferries As community input is an essential part of phased and efficient way. the planning process, BC Ferries held public WHAT opportunities exist to improve the engagement events on May 15, 2018 at the terminal Vancouver Island Conference Centre and May 16, 2018 at the Gabriola Island Arts Council Hall. These events were designed to educate and start a conversation with the residents of both What will Gabriola communities. We want to share with you the and Nanaimo feedback we received. Harbour terminals look like in 2040? Nanaimo Harbour and Gabriola Terminal Development Plans Great terminals are the result of careful planning, financial investment and thoughtful design. We are seeking your feedback on the key issues and draft concepts for Nanaimo Harbour and Gabriola terminals. We want to hear from you about how we can improve them in the future. -

SNUNEYMUXW (First Nation)

Chapter 18 SNUNEYMUXW (First Nation) The single most dangerous action you can take on this tour is failing to pay attention while travelling on the route. Do NOT read the following chapter while actively moving by vehicle, car, foot, bike, or boat. SNUNEYMUXW (First Nation) Driving Tour David Bodaly is a cultural interpreter for the Snuneymuxw First Nation, working on Saysutshun Island. Simon Priest is a past academic and Nanaimo resident with a passion for history and interpretation. Totem Pole, carved by Snuneymuxw Chief Wilkes James, outside the Bank of Montreal, in 1922 (moved to Georgia Park in 1949). Originally called Colviletown, Nanaimo was renamed in 1860. The new name was a mispronunciation of Snuneymuxw (Snoo-nay-mowck), which means “gathering place of a great people.” The Snuneymuxw are Nanaimo’s First Nation and one indigenous Canadian member, among many, of the Coast Salish. Traditional territory of the Coast Salish people COAST SALISH The Coast Salish people occupy coastal lands of British Columbia in Canada, along with coastal lands of Oregon and Washington States in the USA. This map shows the traditional territory of the Coast Salish and identifies the location of the Snuneymuxw people on the Salish Sea within that traditional territory. Coast Salish typically trace lineage along the father’s line of kinship. However, the neighbouring groups outside of Salishan territory, such as the Nuu-chah-nulth (west coast of Vancouver Island) and Kwakiutl/ Kwakwaka’wakw (north island) typically trace inheritance and descent through the mother’s blood line. The latter two groups also speak different languages than the Coast Salish, but share cultural similarities. -

A Stylistic Analysis of the Petroglyphs of Gabriola

VISIONS CAST ON STONE: A STYLISTIC ANALYSIS OF THE PETROGLYPHS OF GABRIOLA ISLAND, B.C. By AMANDA SHEA ADAMS BA. University of California, Berkeley, 2001 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Department of Anthropology and Sociology) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required'standards. THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA DECEMBER 2003 © AMANDA SHEA ADAMS Library Authorization In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Name of Author (please print) Date / • • Title of Thesis: *1//£/CA/£ C/)£7~" &'7~OA*/££-~ S4— Degree: /HA~ Year: sZcTb 3> \ ABSTRACT This study explores the stylistic variability and underlying cohesion of the petroglyphs sites located on Gabriola Island, British Columbia, a southern Gulf Island in the Gulf of Georgia region of the Northwest Coast (North America). I view the petroglyphs as an inter-related body of ancient imagery and deliberately move away from (historical and widespread) attempts at large regional syntheses of 'rock art' and towards a study of smaller and more precise proportion. In this thesis, I propose that the majority of petroglyphs located on Gabriola Island were made in a short period of time, perhaps over the course of a single life (if a single, prolific specialist were responsible for most of the imagery) or, at most, over the course of a few generations (maybe a family of trained carvers). -

Download Download

Chapter 2 The Study Area glomerate blocks), forms an apron along its toe. Be Physical Setting hind False Narrows, a gently-rolling lowland of glacial till and marine sediments, underlain by relatively soft Gabriola Island is situated in the Gulf (Strait) and erodible shales and siltstone, extends from the es of Georgia, a distinct natural region bounded on the carpment westward to the ocean front (Muller 1977). west by the mountain ranges of Vancouver Island, on The area was ice-covered during the last Pleis the east by the Coast Mountains and the Fraser River tocene (Fraser) glaciation, from about 17,000-13,000 canyon, on the north by Seymour Passage, and on the BP (Clague et al. 1982), and since the direction of ice south by Puget Sound (Mitchell 1971). The region as a flow was generally parallel to the axis of the Gulf of whole is characterized by a temperate climate and Georgia, which is also parallel to the bedrock struc abundant and varied food resources, including fishes, tures of Gabriola Island, the lowland-escarpment con shellfish, waterfowl, land and sea mammals, roots, and trast may have been enhanced by selective glacial ero berries, making it an appealing setting for human habi sion of the softer rock. Between 12,000 and 11,500 tation. Of particular importance to the earlier inhabi years ago, when sea level was much higher than at tants were the many streams and rivers flowing into present, the False Narrows bluffs would have formed a Georgia Strait, which attracted the large populations of sea cliff; distinctive honeycomb weathering on some anadromous fish upon which traditional subsistence of the fallen sandstone blocks and rock outcrops sug was based. -

CAC8 Nanaimo Water Aerodrome

CAC8 Nanaimo Water Aerodrome USER GUIDE JULY 2018 v1.20 Contents Thank you! ...................................................................................................................................................... 3 Product requirements .................................................................................................................................. 5 Orbx FTX PACIFIC NORTHWEST IS REQUIRED. .................................................................................. 5 What else will you miss out on if you don’t have Orbx FTX PNW installed? ................................. 6 What’s new in Service Pack 2 (version 1.20) ...................................................................................... 6 What’s new in Service Pack 1 ............................................................................................................... 6 Additional Scenery Features ................................................................................................................ 7 Orbx Trees HD ........................................................................................................................................ 7 Optional ................................................................................................................................................... 9 Quick Installation Guide ............................................................................................................................. 10 Scenery Coverage Area .............................................................................................................................. -

BC Ferries Route Map

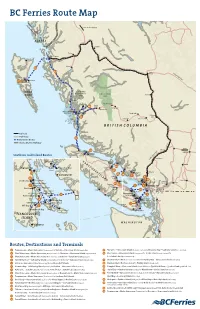

BC Ferries Route Map Alaska Marine Hwy To the Alaska Highway ALASKA Smithers Terrace Prince Rupert Masset Kitimat 11 10 Prince George Yellowhead Hwy Skidegate 26 Sandspit Alliford Bay HAIDA FIORDLAND RECREATION TWEEDSMUIR Quesnel GWAII AREA PARK Klemtu Anahim Lake Ocean Falls Bella 28A Coola Nimpo Lake Hagensborg McLoughlin Bay Shearwater Bella Bella Denny Island Puntzi Lake Williams 28 Lake HAKAI Tatla Lake Alexis Creek RECREATION AREA BRITISH COLUMBIA Railroad Highways 10 BC Ferries Routes Alaska Marine Highway Banff Lillooet Port Hardy Sointula 25 Kamloops Port Alert Bay Southern Gulf Island Routes McNeill Pemberton Duffy Lake Road Langdale VANCOUVER ISLAND Quadra Cortes Island Island Merritt 24 Bowen Horseshoe Bay Campbell Powell River Nanaimo Gabriola River Island 23 Saltery Bay Island Whistler 19 Earls Cove 17 18 Texada Vancouver Island 7 Comox 3 20 Denman Langdale 13 Chemainus Thetis Island Island Hornby Princeton Island Bowen Horseshoe Bay Harrison Penelakut Island 21 Island Hot Springs Hope 6 Vesuvius 22 2 8 Vancouver Long Harbour Port Crofton Alberni Departure Tsawwassen Tsawwassen Tofino Bay 30 CANADA Galiano Island Duke Point Salt Spring Island Sturdies Bay U.S.A. 9 Nanaimo 1 Ucluelet Chemainus Fulford Harbour Southern Gulf Islands 4 (see inset) Village Bay Mill Bay Bellingham Swartz Bay Mayne Island Swartz Bay Otter Bay Port 12 Mill Bay 5 Renfrew Brentwood Bay Pender Islands Brentwood Bay Saturna Island Sooke Victoria VANCOUVER ISLAND WASHINGTON Victoria Seattle Routes, Destinations and Terminals 1 Tsawwassen – Metro Vancouver -

2020 Community Profile

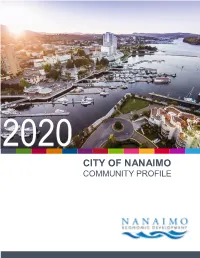

CITY OF NANAIMO COMMUNITY PROFILE 2020 Community Profile MAYOR’S WELCOME On behalf of City Council and the citizens of Nanaimo, it is my pleasure to welcome you to our beautiful city. As the economic hub of central Vancouver Island, Nanaimo boasts both a vibrant business community and an exceptional quality of life. Nanaimo has transitioned from a commodity- based economy that relied on an abundance of natural resources from the forests and ocean towards a service- based “knowledge” economy that relies on the skills, talent and innovation of the local workforce. The city is now a regional centre for health services, technology, retail, construction, manufacturing, education and government services. Nanaimo is a central transportation and distribution hub for Vancouver Island. Home to an excellent deep-sea port, this ocean-side city receives 4.6 million tons (2019) of cargo through its port facilities and deep-sea terminal at Duke Point each year. Air Canada offers direct flights to Vancouver, Calgary and Toronto from the Nanaimo Airport, an all-weather facility. Seaplanes and Helijet link downtown Nanaimo to downtown Vancouver in 20 minutes. BC Ferries provides vehicle and passenger service between Nanaimo and Vancouver as well as Richmond from two terminals located in Nanaimo. Businesses choose to locate in Nanaimo because of the cost efficiencies and a complete range of telecommunications services. Nanaimo offers a well-trained, stable and educated workforce. Vancouver Island University graduates, from various disciplines, provide a constant stream of new employees for area companies. Nanaimo City Council values our over 6,200 businesses and offers support programs through the Economic Development office. -

Five Easy Pieces on the Strait of Georgia – Reflections on the Historical Geography of the North Salish Sea

FIVE EASY PIECES ON THE STRAIT OF GEORGIA – REFLECTIONS ON THE HISTORICAL GEOGRAPHY OF THE NORTH SALISH SEA by HOWARD MACDONALD STEWART B.A., Simon Fraser University, 1975 M.Sc., York University, 1980 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Geography) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) October 2014 © Howard Macdonald Stewart, 2014 Abstract This study presents five parallel, interwoven histories of evolving relations between humans and the rest of nature around the Strait of Georgia or North Salish Sea between the 1850s and the 1980s. Together they comprise a complex but coherent portrait of Canada’s most heavily populated coastal zone. Home to about 10% of Canada’s contemporary population, the region defined by this inland sea has been greatly influenced by its relations with the Strait, which is itself the focus of a number of escalating struggles between stakeholders. This study was motivated by a conviction that understanding this region and the sea at the centre of it, the struggles and their stakeholders, requires understanding of at least these five key elements of the Strait’s modern history. Drawing on a range of archival and secondary sources, the study depicts the Strait in relation to human movement, the Strait as a locus for colonial dispossession of indigenous people, the Strait as a multi-faceted resource mine, the Strait as a valuable waste dump and the Strait as a place for recreation / re-creation. Each of these five dimensions of the Strait’s history was most prominent at a different point in the overall period considered and constantly changing relations among the five narratives are an important focus of the analysis. -

Route Overview

Coastal Ferry Services Contract Schedule A, Appendix 1 - Route Overview ROUTE OVERVIEW - TABLE OF CONTENTS ROUTE GROUP 1 ROUTE 1 – SWARTZ BAY TO TSAWWASSEN ........................................................................................... 2 ROUTE 2 – HORSESHOE BAY TO NANAIMO ............................................................................................. 4 ROUTE 30 – TSAWWASSEN TO DUKE POINT ........................................................................................... 6 ROUTE GROUP 2 ROUTE 3 – HORSESHOE BAY TO LANGDALE .......................................................................................... 8 ROUTE GROUP 3 ROUTE 10 – PORT HARDY TO PRINCE RUPERT......................................................................................10 ROUTE 11 – QUEEN CHARLOTTE ISLANDS TO PRINCE RUPERT.........................................................12 ROUTE 40 – DISCOVERY COAST PASSAGE (PORT HARDY TO MID-COAST) ......................................14 ROUTE GROUP 4 ROUTE 4 – SWARTZ BAY TO FULFORD HARBOUR ................................................................................17 ROUTE 5 – SWARTZ BAY TO GULF ISLANDS ..........................................................................................19 ROUTE 6 – CROFTON TO VESUVIUS BAY ................................................................................................21 ROUTE 7 – EARLS COVE TO SALTERY BAY ............................................................................................23 ROUTE 8 – HORSESHOE BAY -

Nanaimo Estuary Management Plan

NNAANNAAIIMMOO EESSTTUUAARRYY MMAANNAAGGEEMMEENNTT PPLLAANN CATHERINE BERRIS ASSOCIATES INC. February 2006 Canada A CKNOWLEDGEMENTS Steering Committee Department of Fisheries and Oceans: Scott Northrup, Chair Snuneymuxw First Nation: Kathleen Johnnie, (2002 - 2004), Andrew McNaughton (2005) Environment Canada: Ken Brock, Andrew Robinson, Alice Cheung Land and Water B.C. Inc.: Ron Creber (until 2004) Ministry of Environment – Judy Davis (until 2004), Drew Chapman (2005) Nanaimo Port Authority: Mike Davidson Regional District of Nanaimo: Pam Shaw Interest Group Participants in Steering Committee Meetings Nanaimo River Estuary Log Storage Association: Bob Colclough Tim Clermont, The Nature Trust of B.C. Nanaimo Community Estuary Support Coalition: Geoff Robins and Carey McAllister (2004-2005), previously Tony Dorling, Guy Monty, Jack Whitlam Consultants Catherine Berris Associates Inc., Prime Consultant, Planning and Facilitation Catherine Berris, Principal in Charge Bill Gushue, GIS Analysis and Mapping R.U. Kistritz Consultants Ltd., Aquatic Biology Ron Kistritz, Primary Aquatic Biologist Dana Haggarty, Assistant Aquatic Biologist (self employed) Gebauer & Associates Ltd., Terrestrial Biology Martin Gebauer, Terrestrial Biologist Coastal and Ocean Resources Inc., Oceanography Dr. John Harper, Marine Geologist, Project Advisor Snuneymuxw First Nation Technical Support Andrew McNaughton, Shellfish Project Coordinator Kelly Poulin, GIS Coordinator Photographs Andrew McNaughton, Tim Clermont, Scott Northrup and other Steering Committee members -

Regional District of Nanaimo Regional Parks and Trails

REGIONAL DISTRICT OF NANAIMO REGIONAL PARKS AND TRAILS SELECT COMMITTEE REGULAR MEETING TUESDAY, JUNE 16, 2015 12:00pm (RDN Committee Room, 6300 Hammond Bay Road, Nanaimo) A G E N D A PAGES CALL TO ORDER DELEGATIONS Motion to receive late delegation. MINUTES Minutes of the Regular Regional Parks and Trails Advisory Committee meeting held February 3, 2015. Motion to approve Minutes. BUSINESS ARISING FROM THE MINUTES COMMUNICATIONS/CORRESPONDENCE C. Simpson, Island Trust to T. Osborne, RDN, RE: Gabriola Parks Rezoning Bylaws R. O’Donnell, Benson View Rd Resident to W. Marshall, RDN, RE: Mt. Benson Regional Park Parking Issues Motion to receive Communications/Correspondence UNFINISHED BUSINESS REPORTS Monthly Update of Community and Regional Parks and Trails Projects -Jan-April 2015 Morden Colliery Historic Provincial Park – Land Tenure Review Regional Park Dedication Bylaw 1726 Report Mount Benson Regional Park Management Plan – 5 Year Review 1 Regional Parks and Trails Select Committee - Agenda June 16, 2015 Page 2 E&N Rail Trail Costing and Phasing Options Fairwinds Regional Park Management Plan Motion to receive Reports. BUSINESS ARISING FROM DELEGATIONS OR COMMUNICATIONS NEW BUSINESS Park staff – changes to work distribution (handout) IN CAMERA That pursuant to Section 90(1) (e) of the Community Charter the Committee proceed to an In Camera Committee meeting to consider items related to land and legal issues. ADJOURNMENT Motion to adjourn. NEXT MEETING October 20, 2015 Distribution: C. Haime (Chair), A. McPherson, M. Young, J. Fell,