Promenades of an Impressionist by James Huneker

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

16 Exhibition on Screen

Exhibition on Screen - The Impressionists – And the Man Who Made Them 2015, Run Time 97 minutes An eagerly anticipated exhibition travelling from the Musee d'Orsay Paris to the National Gallery London and on to the Philadelphia Museum of Art is the focus of the most comprehensive film ever made about the Impressionists. The exhibition brings together Impressionist art accumulated by Paul Durand-Ruel, the 19th century Parisian art collector. Degas, Manet, Monet, Pissarro, Renoir, and Sisley, are among the artists that he helped to establish through his galleries in London, New York and Paris. The exhibition, bringing together Durand-Ruel's treasures, is the focus of the film, which also interweaves the story of Impressionism and a look at highlights from Impressionist collections in several prominent American galleries. Paintings: Rosa Bonheur: Ploughing in Nevers, 1849 Constant Troyon: Oxen Ploughing, Morning Effect, 1855 Théodore Rousseau: An Avenue in the Forest of L’Isle-Adam, 1849 (Barbizon School) Jean-François Millet: The Gleaners, 1857 (Barbizon School) Jean-François Millet: The Angelus, c. 1857-1859 (Barbizon School) Charles-François Daubigny: The Grape Harvest in Burgundy, 1863 (Barbizon School) Jean-François Millet: Spring, 1868-1873 (Barbizon School) Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot: Ruins of the Château of Pierrefonds, c. 1830-1835 Théodore Rousseau: View of Mont Blanc, Seen from La Faucille, c. 1863-1867 Eugène Delecroix: Interior of a Dominican Convent in Madrid, 1831 Édouard Manet: Olympia, 1863 Pierre Auguste Renoir: The Swing, 1876 16 Alfred Sisley: Gateway to Argenteuil, 1872 Édouard Manet: Luncheon on the Grass, 1863 Edgar Degas: Ballet Rehearsal on Stage, 1874 Pierre Auguste Renoir: Ball at the Moulin de la Galette, 1876 Pierre Auguste Renoir: Portrait of Mademoiselle Legrand, 1875 Alexandre Cabanel: The Birth of Venus, 1863 Édouard Manet: The Fife Player, 1866 Édouard Manet: The Tragic Actor (Rouvière as Hamlet), 1866 Henri Fantin-Latour: A Studio in the Batingnolles, 1870 Claude Monet: The Thames below Westminster, c. -

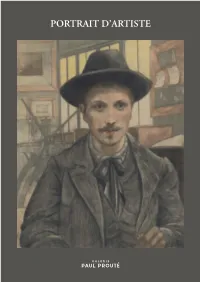

Portrait D'artiste

<--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 210 mm ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------><- 15 mm -><--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 210 mm ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------> 2020 PORTRAIT D’ARTISTE PORTRAIT D’ARTISTE 74, rue de Seine — 75006 Paris Tél. — + 33 (0)1 43 26 89 80 e-mail — [email protected] www.galeriepaulproute.com PAUL PROUTÉ GPP_Portaits_oct2020_CV.indd 1 30/10/2020 16:15:36 GPP_Portaits_oct2020_CV.indd 2 30/10/2020 16:15:37 1920 2020 GPP_Portaits_oct2020_CV.indd 2 30/10/2020 16:15:37 PORTRAIT D’ARTISTE 500 ESTAMPES 2020 SOMMAIRE AVANT-PROPOS .................................................................... 7 PRÉFACE ................................................................................ 9 ESTAMPES DES XVIe ET XVIIe SIÈCLES ............................. 15 ESTAMPES DU XVIIIe SIÈCLE ............................................. 61 ESTAMPES DU XIXe SIÈCLE ................................................ 105 ESTAMPES DU XXe SIÈCLE ................................................. 171 INDEX .................................................................................... 202 AVANT-PROPOS près avoir quitté la maison familiale du 12 de la rue de Seine, Paul Prouté s’instal- Alait au 74 de cette même rue le 15 janvier -

Masterpiece: Monet Painting in His Garden, 1913 by Pierre Auguste Renoir

Masterpiece: Monet Painting in His Garden, 1913 by Pierre Auguste Renoir Pronounced: REN WAUR Keywords: Impressionism, Open Air Painting Grade: 3rd Grade Month: November Activity: “Plein Air” Pastel Painting TIME: 1 - 1.25 hours Overview of the Impressionism Art Movement: Impressionism was a style of painting that became popular over 100 years ago mainly in France. Up to this point in the art world, artists painted people and scenery in a realistic manner. A famous 1872 painting by Claude Monet named “Impression: Sunrise ” was the inspiration for the name given to this new form of painting: “Impressionism” (See painting below) by an art critic. Originally the term was meant as an insult, but Monet embraced the name. The art institutes of the day thought that the paintings looked unfinished, or childlike. Characteristics of Impressionist paintings include: visible brush strokes, open composition, light depicting the effects of the passage of time, ordinary subject matter, movement, and unusual visual angles. As a technique, impressionists used dabs of paint (often straight out of a paint tube) to recreate the impression they saw of the light and the effects the light had on color. Due to this, most Impressionistic artists painted in the “plein-air”, French for open air. The important concept for 3 rd grade lessons is the Impressionism movement was short lived but inspired other artists from all over, including America, to begin using this new technique. Each of the artists throughout the lessons brought something new and a little different to advance the Impressionistic years. (i.e. Seurat with Neo-Impressionism and Toulouse-Lautrec with Post-Impressionism). -

The Library of Professor Eric G. Carlson

The Library of Professor Eric G. Carlson Part II: Rare Illustrated Books and Print Portfolios, ca. 1850-1930 405 titles, in ca. 585 physical volumes The Library of Professor Eric G. Carlson Part I: Art of France from the French Revolution to the End of the Third Republic, 1790-1940. General Reference Works and Monographs on Artists, with a special emphasis on prints and printmaking The art historian and art dealer Eric G. Carlson (1940-2016) was a noted specialist in French and American prints and drawings of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. A mediaevalist by training (Ph.D. Yale University), and professor at the State University of New York at Purchase from 1978 to 2006, Carlson brought a scholar's acumen to his exploration of lesser-known fields and figures of French art. His library reflects this, being exceptionally rich not just on the major artists of the era, but on the many painters and printmakers who remain to this day little known to the general public. Its coverage of the art of Romanticism, Realism, and Post-Impressionism, with very impressive concentrations on Géricault, Delacroix, Courbet, Degas and Gauguin, among others, is matched by a fascinating depth in the Symbolist and Nabi movements and the School of Pont-Aven, and the myriad Academic and Salon artists, illustrators and caricaturists who flourished between the start of the Second Empire and the end of the Third Republic. The library is unusually complete and sophisticated in the documentation and critical study of all aspects of the period, with rare exhibition and auction catalogues, and scarce early monographs, as well as the latest academic scholarship. -

Vincent Van Gogh the Starry Night

Richard Thomson Vincent van Gogh The Starry Night the museum of modern art, new york The Starry Night without doubt, vincent van gogh’s painting the starry night (fig. 1) is an iconic image of modern culture. One of the beacons of The Museum of Modern Art, every day it draws thousands of visitors who want to gaze at it, be instructed about it, or be photographed in front of it. The picture has a far-flung and flexible identity in our collective musée imaginaire, whether in material form decorating a tie or T-shirt, as a visual quotation in a book cover or caricature, or as a ubiquitously understood allusion to anguish in a sentimental popular song. Starry Night belongs in the front rank of the modern cultural vernacular. This is rather a surprising status to have been achieved by a painting that was executed with neither fanfare nor much explanation in Van Gogh’s own correspondence, that on reflection the artist found did not satisfy him, and that displeased his crucial supporter and primary critic, his brother Theo. Starry Night was painted in June 1889, at a period of great complexity in Vincent’s life. Living at the asylum of Saint-Rémy in the south of France, a Dutchman in Provence, he was cut off from his country, family, and fellow artists. His isolation was enhanced by his state of health, psychologically fragile and erratic. Yet for all these taxing disadvantages, Van Gogh was determined to fulfill himself as an artist, the road that he had taken in 1880. -

Claude Monet (1840-1926)

Caroline Mc Corriston Claude Monet (1840-1926) ● Monet was the leading figure of the impressionist group. ● As a teenager in Normandy he was brought to paint outdoors by the talented painter Eugéne Boudin. Boudin taught him how to use oil paints. ● Monet was constantly in financial difficulty. His paintings were rejected by the Salon and critics attacked his work. ● Monet went to Paris in 1859. He befriended the artists Cézanne and Pissarro at the Academie Suisse. (an open studio were models were supplied to draw from and artists paid a small fee).He also met Courbet and Manet who both encouraged him. ● He studied briefly in the teaching studio of the academic history painter Charles Gleyre. Here he met Renoir and Sisley and painted with them near Barbizon. ● Every evening after leaving their studies, the students went to the Cafe Guerbois, where they met other young artists like Cezanne and Degas and engaged in lively discussions on art. ● Monet liked Japanese woodblock prints and was influenced by their strong colours. He built a Japanese bridge at his home in Giverny. Monet and Impressionism ● In the late 1860s Monet and Renoir painted together along the Seine at Argenteuil and established what became known as the Impressionist style. ● Monet valued spontaneity in painting and rejected the academic Salon painters’ strict formulae for shading, geometrically balanced compositions and linear perspective. ● Monet remained true to the impressionist style but went beyond its focus on plein air painting and in the 1890s began to finish most of his work in the studio. Personal Style and Technique ● Use of pure primary colours (straight from the tube) where possible ● Avoidance of black ● Addition of unexpected touches of primary colours to shadows ● Capturing the effect of sunlight ● Loose brushstrokes Subject Matter ● Monet painted simple outdoor scenes in the city, along the coast, on the banks of the Seine and in the countryside. -

Prints and Their Production; a List of Works in the New York Public Library

N E UC-NRLF PRINTS AND THEIR PRODUCTION A LIST OF WORKS IN THE NEW YORK PUPUBLIC LIBRARY COMPILED BY FRANK WEITENKAMPF, L.H.D. CHIEF, ART AND PRINTS DIVISION NEW YORK PUBLIC LIB-RARY 19 l6 ^4^ NOTE to This list contains the titles of works relating owned the prints and their production, by Reference on Department of The New York Public Library in the Central Build- November 1, 1915. They are Street. ing, at Fifth Avenue and Forty-second Reprinted September 1916 FROM THE Bulletin of The New York Public Library November - December 1915 form p-02 [ix-20-lfl 25o] CONTENTS I. Prints as Art Products PAGE - - Bibliography 1 Individual Artists - - 2>7 - 2 General and Miscellaneous Works Special Processes - - _ . 79 Periodicals and Societies - - - 3 Etching - - - - - - 79 Processes: Line Engraving and Proc- Handbooks (Technical) - - 79 esses IN General - - - 4 History - 81 Regional - ----- 82 Handbooks for the Student and Col- (Subdivided lector ------ 6 by countries.) Stipple 84 Sales and Prices: General Works - 7 Mezzotint - 84 Extra-Illustration - - - - 8 Aquatint 86 Care of Prints ----- 8 Dotted Prints (Maniere Criblee; History (General) . - _ _ 9 Schrotblatter) - - - - 86 Nielli -_--__ H Wood Engraving - - - - 86 Paste Prints ("Teigdrucke") - - 12 Handbooks (Technical) - - 87 Reproductions of Prints - - - 12 History ------ 87 History (Regional) - - - - 13 Block-books ----- 89 (Subdivided by countries; includes History: Regional- - - - 90 Japanese prints.) (Subdivided by countries.) Dictionaries of Artists - - - 26 Lithography ----- 91 Exhibitions (General and Miscel- Handbooks (Technical) - - 91 laneous) 29 History ------ 94 Collections (Public) - - - - 31 Regional - 95 (Subdivided by countries.) (Subdivided by countries.) Collections (Private) - - - - 34 Color Prints ----- 96 II. -

A 'Physics of Thought': the Modernist Materialism of James Huneker

IAN F. A. B ELL A ‘Physics of Thought’: The Modernist Materialism of James Huneker Nature geometrizes, said Emerson, and it is interesting to note the imagery of transcendentalism through the ages. It is invariably geometrical. Spheres, planes, cones, circles, spirals, tetragrams, pentagrams, ellipses, and what-not. This is Huneker’s ‘Four Dimensional Vistas’ and thoroughly in line with the modernist scientism of figures such as Ezra Pound and Remy de Gourmont (the latter was pre-eminent in his pantheon of cosmopolitan thinkers). He shores up his argument by claiming these geometrical pat- terns as products of a discernable physiology: ‘The precise patterns in our brain, like those of the ant, bee and beaver, which enable us to perceive and build the universe (otherwise called innate ideas) are geo- metrical’ (206). His displacement of ‘ideas’ by the language of construction presents a challenge to the experienced world whereby matter itself is seen to be not solidly deterministic, but subject to flow and process, as he claimed in ‘Creative Involution’: ‘Matter in the light of recent experiment is become spirit, energy, anything but gross matter’.1 Huneker’s essay on ‘Remy de Gourmont: His Ideas. The Colour of His Mind’ asserted baldly that ‘[t]hought is a physiological product; intelli- gence the secretion of matter’ while Gourmont himself was equally as bald: ‘Thought is not only a product, but a material product, measur- able, ponderable’(27; 166). In short, a crucial aspect of Huneker’s modernism is his supplanting of a mechanistic understanding of matter by invoking a plasticity sanctioned by current scientific thinking. -

The Drawings of Cornelis Visscher (1628/9-1658) John Charleton

The Drawings of Cornelis Visscher (1628/9-1658) John Charleton Hawley III Jamaica Plain, MA M.A., History of Art, Institute of Fine Arts – New York University, 2010 B.A., Art History and History, College of William and Mary, 2008 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Art and Architectural History University of Virginia May, 2015 _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................................................. i Acknowledgements.......................................................................................................................... ii Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1: The Life of Cornelis Visscher .......................................................................................... 3 Early Life and Family .................................................................................................................... 4 Artistic Training and Guild Membership ...................................................................................... 9 Move to Amsterdam ................................................................................................................. -

On Art and Artists

A/ 'PI CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY FINE ARTS LIBRARY Cornell University Library N 7445.N82 1907 On art and artists, 3 1924 020 584 946 DATE DUE PRINTEDINU.S./I Cornell University Library The original of tiiis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924020584946 ON ART AND ARTISTS Photo : Elhott and Fry. On A H and A rtisls. ON ART AND ARTISTS BY MAX NORDAU AUTHOR OF " DEGBNBRATION " TRANSLATED BY W. F. HARVEY, M.A. PHILADELPHIA GEORGE W. JACOBS & CO. PUBUSHERS 11 n Printed in Great Britain. CONTENTS CHAF. PACE I. The Social Mission of Art. i II. Socialistic Art—Constantin Meunier . 30 in. The Question of Style .... 44 IV. The Old French Masters . .56 V. A Century of French Art .... 70 VI. The School of 1830 ..... 96 VII. The Triumph of a Revolution— The Realists . .107 Alfred Sisley ..... 123 Camille Pissarro . .133 Whistler's Psychology . .145 VIII. Gustave Moreau ..... 155 " IX. EUGilNE CARRlfeRE . l66 X. Puvis DE Chavannes ..... i8s XL Bright and Dark Painting—Charles Cottet . 201 XII. Physiognomies in Painting . .217 XIII. Augusts Rodin ..... 275 XIV. Resurrection—BARTHOLOMi . 294 XV. Jean CarriSis ...... 308 XVI. Works of Art and Art Criticisms . 320 XVII. Mt Own Opinion ..... 336 Index ....... 349 : ON ART AND ARTISTS I THE SOCIAL MISSION OF ART There exists a school of aestheticism which laughs contemptuously at the mere sight of this superscrip- tion. Art having a mission ! What utter nonsense. A person must be a rank Philistine to connect with the idea of art the conception of a non- artistic mission, be it social or otherwise. -

The ART of Wine

The ART of Wine VINUM VINE “ Drink wine and tomorrow we will wake, Drink love and we shall be drunk forever... ” T had my first taste of wine at 6 p.m. a couple years ago; during an Organic Chemistry II lecture (held in one of the largest University lecture halls in America (200 + seats)). I I sip wine, while knowing the consequence and taboos of in-class alcohol consumption. It was an Italian 187 mL imported Merlot Cavit Collection, screw capped; which was enjoyed with six French’s cinnamon raisin cookies. While enjoying, I was learning about aromatic compounds and carbon cation. On May 25, 2010: I have decided to publish my story. This book is not about wine; it’s about what you can do with the idea. Cheers, and enjoy! Nymphs offering Bacchus wine (1670-78) : Caesar Van Everdingen In the 1600s, the Benedictine monks invented bottle stompers out of wood and rags. 150 years later, Spain invented the first cork stopper. Then came the invention of a corkscrew Alison Brewster Tiffany & Co. Alessi Georg Jensen Alessi Alessandro M. Typography is emotional and complex. For the love of typography; we toast to a few great fonts. Ned Wright The Leasing Studio Sohne Stockholm Design Lab Gut Oggau Portrait Wines | Jung Von Matt Meeta Panesar Designs, with Op Art tradition of Joseph Albers Matsu Wine. “El Picaro”, “El Recio”, and “El Viejo” | Javier Euba of Moruba, an organic wine from Tor D.O. Click Wine Group | Bootleg Wine The colors represent Pinot Grigio, Sauvignon Blanc, Chianti, Southern Red, and Grand Tuscan. -

The Story of the Borgias (1913)

The Story of The Borgias John Fyvie L1BRARV OF UN ,VERSITV CALIFORNIA AN DIEGO THE STORY OF THE BORGIAS <Jt^- i//sn6Ut*4Ccn4<s flom fte&co-^-u, THE STORY OF THE BOEGIAS AUTHOR OF "TRAGEDY QUEENS OF THE GEORGIAN ERA" ETC NEW YORK G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS 1913 PRINTED AT THE BALLANTYNE PRESS TAVI STOCK STREET CoVENT GARDEN LONDON THE story of the Borgia family has always been of interest one strangely fascinating ; but a lurid legend grew up about their lives, which culminated in the creation of the fantastic monstrosities of Victor Hugo's play and Donizetti's opera. For three centuries their name was a byword for the vilest but in our there has been infamy ; own day an extraordinary swing of the pendulum, which is hard to account for. Quite a number of para- doxical writers have proclaimed to an astonished and mystified world that Pope Alexander VI was both a wise prince and a gentle priest whose motives and actions have been maliciously mis- noble- represented ; that Cesare Borgia was a minded and enlightened statesman, who, three centuries in advance of his time, endeavoured to form a united Italy by the only means then in Lucrezia anybody's power ; and that Borgia was a paragon of all the virtues. " " It seems to have been impossible to whitewash the Borgia without a good deal of juggling with the evidence, as well as a determined attack on the veracity and trustworthiness of the contemporary b v PREFACE historians and chroniclers to whom we are indebted for our knowledge of the time.