What Do Names Tell Us About Our Former Occupations?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ancient Mesopotamian Place Name “Meluḫḫa”

THE ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIAN PLACE NAME “meluḫḫa” Stephan Hillyer Levitt INTRODUCTION The location of the Ancient Mesopotamian place name “Meluḫḫa” has proved to be difficult to determine. Most modern scholars assume it to be the area we associate with Indus Valley Civilization, now including the so-called Kulli culture of mountainous southern Baluchistan. As far as a possible place at which Meluḫḫa might have begun with an approach from the west, Sutkagen-dor in the Dasht valley is probably as good a place as any to suggest (Possehl 1996: 136–138; for map see 134, fig. 1). Leemans argued that Meluḫḫa was an area beyond Magan, and was to be identified with the Sind and coastal regions of Western India, including probably Gujarat. Magan he identified first with southeast Arabia (Oman), but later with both the Arabian and Persian sides of the Gulf of Oman, thus including the southeast coast of Iran, the area now known as Makran (1960a: 9, 162, 164; 1960b: 29; 1968: 219, 224, 226). Hansman identifies Meluḫḫa, on the basis of references to products of Meluḫḫa being brought down from the mountains, as eastern Baluchistan in what is today Pakistan. There are no mountains in the Indus plain that in its southern extent is Sind. Eastern Baluchistan, on the other hand, is marked throughout its southern and central parts by trellised ridges that run parallel to the western edge of the Indus plain (1973: 559–560; see map [=fig. 1] facing 554). Thapar argues that it is unlikely that a single name would refer to the entire area of a civilization as varied and widespread as Indus Valley Civilization. -

Surnames in Europe

DOI: http://dx.doi.org./10.17651/ONOMAST.61.1.9 JUSTYNA B. WALKOWIAK Onomastica LXI/1, 2017 Uniwersytet im. Adama Mickiewicza w Poznaniu PL ISSN 0078-4648 [email protected] FUNCTION WORDS IN SURNAMES — “ALIEN BODIES” IN ANTHROPONYMY (WITH PARTICULAR REFERENCE TO POLAND) K e y w o r d s: multipart surnames, compound surnames, complex surnames, nobiliary particles, function words in surnames INTRODUCTION Surnames in Europe (and in those countries outside Europe whose surnaming patterns have been influenced by European traditions) are mostly conceptualised as single entities, genetically nominal or adjectival. Even if a person bears two or more surnames, they are treated on a par, which may be further emphasized by hyphenation, yielding the phenomenon known as double-barrelled (or even multi-barrelled) surnames. However, this single-entity approach, visible e.g. in official forms, is largely an oversimplification. This becomes more obvious when one remembers such household names as Ludwig van Beethoven, Alexander von Humboldt, Oscar de la Renta, or Olivia de Havilland. Contemporary surnames resulted from long and complicated historical processes. Consequently, certain surnames contain also function words — “alien bodies” in the realm of proper names, in a manner of speaking. Among these words one can distinguish: — prepositions, such as the Portuguese de; Swedish von, af; Dutch bij, onder, ten, ter, van; Italian d’, de, di; German von, zu, etc.; — articles, e.g. Dutch de, het, ’t; Italian l’, la, le, lo — they will interest us here only when used in combination with another category, such as prepositions; — combinations of prepositions and articles/conjunctions, or the contracted forms that evolved from such combinations, such as the Italian del, dello, del- la, dell’, dei, degli, delle; Dutch van de, van der, von der; German von und zu; Portuguese do, dos, da, das; — conjunctions, e.g. -

IN TAX LEADERS WOMEN in TAX LEADERS | 4 AMERICAS Latin America

WOMEN IN TAX LEADERS THECOMPREHENSIVEGUIDE TO THE WORLD’S LEADING FEMALE TAX ADVISERS SIXTH EDITION IN ASSOCIATION WITH PUBLISHED BY WWW.INTERNATIONALTAXREVIEW.COM Contents 2 Introduction and methodology 8 Bouverie Street, London EC4Y 8AX, UK AMERICAS Tel: +44 20 7779 8308 4 Latin America: 30 Costa Rica Fax: +44 20 7779 8500 regional interview 30 Curaçao 8 United States: 30 Guatemala Editor, World Tax and World TP regional interview 30 Honduras Jonathan Moore 19 Argentina 31 Mexico Researchers 20 Brazil 31 Panama Lovy Mazodila 24 Canada 31 Peru Annabelle Thorpe 29 Chile 32 United States Jason Howard 30 Colombia 41 Venezuela Production editor ASIA-PACIFIC João Fernandes 43 Asia-Pacific: regional 58 Malaysia interview 59 New Zealand Business development team 52 Australia 60 Philippines Margaret Varela-Christie 53 Cambodia 61 Singapore Raquel Ipo 54 China 61 South Korea Managing director, LMG Research 55 Hong Kong SAR 62 Taiwan Tom St. Denis 56 India 62 Thailand 58 Indonesia 62 Vietnam © Euromoney Trading Limited, 2020. The copyright of all 58 Japan editorial matter appearing in this Review is reserved by the publisher. EUROPE, MIDDLE EAST & AFRICA 64 Africa: regional 101 Lithuania No matter contained herein may be reproduced, duplicated interview 101 Luxembourg or copied by any means without the prior consent of the 68 Central Europe: 102 Malta: Q&A holder of the copyright, requests for which should be regional interview 105 Malta addressed to the publisher. Although Euromoney Trading 72 Northern & 107 Netherlands Limited has made every effort to ensure the accuracy of this Southern Europe: 110 Norway publication, neither it nor any contributor can accept any regional interview 111 Poland legal responsibility whatsoever for consequences that may 86 Austria 112 Portugal arise from errors or omissions, or any opinions or advice 87 Belgium 115 Qatar given. -

Bramwell, Ellen S. (2012) Naming in Society: a Cross-Cultural Study of Five Communities in Scotland

Bramwell, Ellen S. (2012) Naming in society: a cross-cultural study of five communities in Scotland. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/3173/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ENGLISH LANGUAGE, COLLEGE OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW Naming in Society A cross-cultural study of five communities in Scotland Ellen Sage Bramwell September 2011 © Ellen S. Bramwell 2011 Abstract Personal names are a human universal, but systems of naming vary across cultures. While a person’s name identifies them immediately with a particular cultural background, this aspect of identity is rarely researched in a systematic way. This thesis examines naming patterns as a product of the society in which they are used. Personal names have been studied within separate disciplines, but to date there has been little intersection between them. This study marries approaches from anthropology and linguistic research to provide a more comprehensive approach to name-study. Specifically, this is a cross-cultural study of the naming practices of several diverse communities in Scotland, United Kingdom. -

Role of Endolysosomes and Inter-Organellar Signaling in Brain Disease

University of North Dakota UND Scholarly Commons Biomedical Sciences Faculty Publications Department of Biomedical Sciences 2-2020 Role of endolysosomes and inter-organellar signaling in brain disease Zahra Afghah Xuesong Chen University of North Dakota, [email protected] Jonathan David Geiger University of North Dakota, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.und.edu/bms-fac Part of the Medicine and Health Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Afghah, Zahra; Chen, Xuesong; and Geiger, Jonathan David, "Role of endolysosomes and inter-organellar signaling in brain disease" (2020). Biomedical Sciences Faculty Publications. 1. https://commons.und.edu/bms-fac/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Biomedical Sciences at UND Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Biomedical Sciences Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UND Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Neurobiology of Disease 134 (2020) 104670 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Neurobiology of Disease journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ynbdi Review Role of endolysosomes and inter-organellar signaling in brain disease T ⁎ Zahra Afghah, Xuesong Chen, Jonathan D. Geiger Department of Biomedical Sciences, University of North Dakota School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Grand Forks, North Dakota 58201, United States of America ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Endosomes and lysosomes (endolysosomes) are membrane bounded organelles that play a key role in cell sur- Endolysosomes vival and cell death. These acidic intracellular organelles are the principal sites for intracellular hydrolytic Mitochondria activity required for the maintenance of cellular homeostasis. -

Influence of Pathogenic Bacterial Determinants on Genome

INFLUENCE OF PATHOGENIC BACTERIAL DETERMINANTS ON GENOME STABILITY OF EXPOSED INTESTINAL CELLS AND OF DISTAL LIVER AND SPLEEN CELLS Paul S. Walz B.Sc. Hons., University of Western Ontario, 2009 A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies of the University of Lethbridge in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTERS OF SCIENCE Department of Biology University of Lethbridge LETHBRIDGE, ALBERTA, CANADA © Paul S. Walz, 2011 INFLUENCE OF PATHOGENIC BACTERIAL DETERMINANTS ON GENOME STABILITY OF EXPOSED INTESTINAL CELLS AND OF DISTAL LIVER AND SPLEEN CELLS Paul S. Walz Approved Dr. Igor Kovalchuk, Co-Supervisor, Department of Biological Science, MD, PhD Date Dr. Olga Kovalchuk, Co-Supervisor, Department of Biological Science, MD, PhD Date Dr. Brent Selinger, Thesis Committee Member, Department of Biological Science, PhD Date Dr. James Thomas, Thesis Committee Member, Department of Biological Science, PhD Date Dr. Lesley Brown, Thesis Committee Member, Department of Kinesiology & Phys. Ed., PhD Date Dr. Elizabeth Schultz/Dr. Theresa Burg, Chair, Department of Biological Science, PhD Date ABSTRACT Most bacterial infections can be correlated to contamination of consumables such as food and water. Upon contamination, boil water advisories have been ordered to ensure water is safe to consume, despite the evidence that heat-killed bacteria can induce genomic instability of exposed (intestine) and distal cells (liver and spleen). We hypothesize that exposure to components of heat-killed Escherichia coli O157:H7 will induce genomic instability within animal cells directly and indirectly exposed to these determinants. Mice were exposed to various components of dead bacteria such as DNA, RNA, protein or LPS as well as to whole heat-killed bacteria via drinking water. -

Male Names in X-Son in Brazilian Anthroponymy: a Morphological, Historical, and Constructional Approach

Revista de Estudos da Linguagem, v. 26, n. 3, p. 1295-1350, 2018 Male Names in X-Son in Brazilian Anthroponymy: a Morphological, Historical, and Constructional Approach Nomes masculinos X-son na antroponímia brasileira: uma abordagem morfológica, histórica e construcional Natival Almeida Simões Neto Universidade Estadual de Feira de Santana (UEFS), Feira de Santana, Bahia / Brasil [email protected] Juliana Soledade Universidade Federal da Bahia (UFBA), Salvador, Bahia / Brasil Universidade de Brasília (UnB), Brasília, DF / Brasil [email protected] Resumo: Neste trabalho, pretendemos fazer uma análise de nomes masculinos terminados em -son na lista de aprovados dos vestibulares de 2016 e 2017 da Universidade do Estado da Bahia, como Anderson, Jefferson, Emerson, Radson, Talison, Erickson e Esteferson. Ao todo, foram registrados 96 nomes graficamente diferentes. Esses nomes, quando possível, foram analisados do ponto de vista etimológico, com base em consultas nos dicionários onomásticos de língua portuguesa de Nascentes (1952) e de Machado (1981), além de dicionários de língua inglesa, como os de Arthur (1857) e Reaney e Willson (2006). Foram também utilizados como materiais de análise a Lista de nomes admitidos em Portugal, encontrada no site do Instituto dos Registos e do Notariado, de Portugal, e a Plataforma Nomes no Brasil, disponível no site do Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Quanto às análises morfológicas aqui empreendidas, utilizamos como aporte teórico-metodológico a Morfologia Construcional, da maneira proposta por Booij (2010), Soledade (2013), Gonçalves (2016a), Simões Neto (2016) e Rodrigues (2016). Em linhas gerais, o artigo vislumbra observar a trajetória do formativo –son na criação de antropônimos no Brasil. Para isso, eISSN: 2237-2083 DOI: 10.17851/2237-2083.26.3.1295-1350 1296 Revista de Estudos da Linguagem, v. -

Family Group Sheets Surname Index

PASSAIC COUNTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY FAMILY GROUP SHEETS SURNAME INDEX This collection of 660 folders contains over 50,000 family group sheets of families that resided in Passaic and Bergen Counties. These sheets were prepared by volunteers using the Societies various collections of church, ceme tery and bible records as well as city directo ries, county history books, newspaper abstracts and the Mattie Bowman manuscript collection. Example of a typical Family Group Sheet from the collection. PASSAIC COUNTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY FAMILY GROUP SHEETS — SURNAME INDEX A Aldous Anderson Arndt Aartse Aldrich Anderton Arnot Abbott Alenson Andolina Aronsohn Abeel Alesbrook Andreasen Arquhart Abel Alesso Andrews Arrayo Aber Alexander Andriesse (see Anderson) Arrowsmith Abers Alexandra Andruss Arthur Abildgaard Alfano Angell Arthurs Abraham Alje (see Alyea) Anger Aruesman Abrams Aljea (see Alyea) Angland Asbell Abrash Alji (see Alyea) Angle Ash Ack Allabough Anglehart Ashbee Acker Allee Anglin Ashbey Ackerman Allen Angotti Ashe Ackerson Allenan Angus Ashfield Ackert Aller Annan Ashley Acton Allerman Anners Ashman Adair Allibone Anness Ashton Adams Alliegro Annin Ashworth Adamson Allington Anson Asper Adcroft Alliot Anthony Aspinwall Addy Allison Anton Astin Adelman Allman Antoniou Astley Adolf Allmen Apel Astwood Adrian Allyton Appel Atchison Aesben Almgren Apple Ateroft Agar Almond Applebee Atha Ager Alois Applegate Atherly Agnew Alpart Appleton Atherson Ahnert Alper Apsley Atherton Aiken Alsheimer Arbuthnot Atkins Aikman Alterman Archbold Atkinson Aimone -

Marriage Certificates

GROOM LAST NAME GROOM FIRST NAME BRIDE LAST NAME BRIDE FIRST NAME DATE PLACE Abbott Calvin Smerdon Dalkey Irene Mae Davies 8/22/1926 Batavia Abbott George William Winslow Genevieve M. 4/6/1920Alabama Abbotte Consalato Debale Angeline 10/01/192 Batavia Abell John P. Gilfillaus(?) Eleanor Rose 6/4/1928South Byron Abrahamson Henry Paul Fullerton Juanita Blanche 10/1/1931 Batavia Abrams Albert Skye Berusha 4/17/1916Akron, Erie Co. Acheson Harry Queal Margaret Laura 7/21/1933Batavia Acheson Herbert Robert Mcarthy Lydia Elizabeth 8/22/1934 Batavia Acker Clarence Merton Lathrop Fannie Irene 3/23/1929East Bethany Acker George Joseph Fulbrook Dorothy Elizabeth 5/4/1935 Batavia Ackerman Charles Marshall Brumsted Isabel Sara 9/7/1917 Batavia Ackerson Elmer Schwartz Elizabeth M. 2/26/1908Le Roy Ackerson Glen D. Mills Marjorie E. 02/06/1913 Oakfield Ackerson Raymond George Sherman Eleanora E. Amelia 10/25/1927 Batavia Ackert Daniel H. Fisher Catherine M. 08/08/1916 Oakfield Ackley Irving Amos Reid Elizabeth Helen 03/17/1926 Le Roy Acquisto Paul V. Happ Elsie L. 8/27/1925Niagara Falls, Niagara Co. Acton Robert Edward Derr Faith Emma 6/14/1913Brockport, Monroe Co. Adamowicz Ian Kizewicz Joseta 5/14/1917Batavia Adams Charles F. Morton Blanche C. 4/30/1908Le Roy Adams Edward Vice Jane 4/20/1908Batavia Adams Edward Albert Considine Mary 4/6/1920Batavia Adams Elmer Burrows Elsie M. 6/6/1911East Pembroke Adams Frank Leslie Miller Myrtle M. 02/22/1922 Brockport, Monroe Co. Adams George Lester Rebman Florence Evelyn 10/21/1926 Corfu Adams John Benjamin Ford Ada Edith 5/19/1920Batavia Adams Joseph Lawrence Fulton Mary Isabel 5/21/1927Batavia Adams Lawrence Leonard Boyd Amy Lillian 03/02/1918 Le Roy Adams Newton B. -

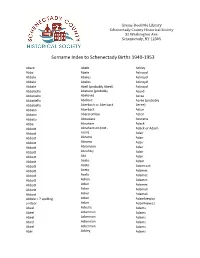

Surname Index to Schenectady Births 1940-1953

Grems-Doolittle Library Schenectady County Historical Society 32 Washington Ave. Schenectady, NY 12305 Surname Index to Schenectady Births 1940-1953 Abare Abele Ackley Abba Abele Ackroyd Abbale Abeles Ackroyd Abbale Abeles Ackroyd Abbale Abell (probably Abeel) Ackroyd Abbatiello Abelone (probably Acord Abbatiello Abelove) Acree Abbatiello Abelove Acree (probably Abbatiello Aberbach or Aberback Aeree) Abbato Aberback Acton Abbato Abercrombie Acton Abbato Aboudara Acucena Abbe Abraham Adack Abbott Abrahamson (not - Adack or Adach Abbott nson) Adair Abbott Abrams Adair Abbott Abrams Adair Abbott Abramson Adair Abbott Abrofsky Adair Abbott Abt Adair Abbott Aceto Adam Abbott Aceto Adamczak Abbott Aceto Adamec Abbott Aceto Adamec Abbott Acken Adamec Abbott Acker Adamec Abbott Acker Adamek Abbott Acker Adamek Abbzle = ? spelling Acker Adamkiewicz unclear Acker Adamkiewicz Abeel Ackerle Adams Abeel Ackerman Adams Abeel Ackerman Adams Abeel Ackerman Adams Abeel Ackerman Adams Abel Ackley Adams Grems-Doolittle Library Schenectady County Historical Society 32 Washington Ave. Schenectady, NY 12305 Surname Index to Schenectady Births 1940-1953 Adams Adamson Ahl Adams Adanti Ahles Adams Addis Ahman Adams Ademec or Adamec Ahnert Adams Adinolfi Ahren Adams Adinolfi Ahren Adams Adinolfi Ahrendtsen Adams Adinolfi Ahrendtsen Adams Adkins Ahrens Adams Adkins Ahrens Adams Adriance Ahrens Adams Adsit Aiken Adams Aeree Aiken Adams Aernecke Ailes = ? Adams Agans Ainsworth Adams Agans Aker (or Aeher = ?) Adams Aganz (Agans ?) Akers Adams Agare or Abare = ? Akerson Adams Agat Akin Adams Agat Akins Adams Agen Akins Adams Aggen Akland Adams Aggen Albanese Adams Aggen Alberding Adams Aggen Albert Adams Agnew Albert Adams Agnew Albert or Alberti Adams Agnew Alberti Adams Agostara Alberti Adams Agostara (not Agostra) Alberts Adamski Agree Albig Adamski Ahave ? = totally Albig Adamson unclear Albohm Adamson Ahern Albohm Adamson Ahl Albohm (not Albolm) Adamson Ahl Albrezzi Grems-Doolittle Library Schenectady County Historical Society 32 Washington Ave. -

Characterization of Visceral and Subcutaneous Adipose Tissue

J. Perinat. Med. 2016; 44(7): 813–835 Shali Mazaki-Tovi*, Adi L. Tarca, Edi Vaisbuch, Juan Pedro Kusanovic, Nandor Gabor Than, Tinnakorn Chaiworapongsa, Zhong Dong, Sonia S. Hassan and Roberto Romero* Characterization of visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue transcriptome in pregnant women with and without spontaneous labor at term: implication of alternative splicing in the metabolic adaptations of adipose tissue to parturition DOI 10.1515/jpm-2015-0259 groups (unpaired analyses) and adipose tissue regions Received July 27, 2015. Accepted October 26, 2015. Previously (paired analyses). Selected genes were tested by quantita- published online March 19, 2016. tive reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction. Abstract Results: Four hundred and eighty-two genes were differ- entially expressed between visceral and subcutaneous Objective: The aim of this study was to determine gene fat of pregnant women with spontaneous labor at term expression and splicing changes associated with par- (q-value < 0.1; fold change > 1.5). Biological processes turition and regions (visceral vs. subcutaneous) of the enriched in this comparison included tissue and vascu- adipose tissue of pregnant women. lature development as well as inflammatory and meta- Study design: The transcriptome of visceral and abdomi- bolic pathways. Differential splicing was found for 42 nal subcutaneous adipose tissue from pregnant women at genes [q-value < 0.1; differences in Finding Isoforms using term with (n = 15) and without (n = 25) spontaneous labor Robust Multichip Analysis scores > 2] between adipose was profiled with the Affymetrix GeneChip Human Exon tissue regions of women not in labor. Differential exon 1.0 ST array. Overall gene expression changes and the dif- usage associated with parturition was found for three ferential exon usage rate were compared between patient genes (LIMS1, HSPA5, and GSTK1) in subcutaneous tissues. -

Start Number Name Surname Team City, Country Time 11001 Tommy

Start number Name Surname Team City, Country Time 11001 Tommy Frølund Jensen Kongens lyngby, Denmark 89:20:46 11002 Emil Boström Lag Nord Linköping, Sweden 98:19:04 11003 Lovisa Johansson Lag Nord Burträsk, Sweden 98:19:02 11005 Maurice Lagershausen Huddinge, Sweden 102:01:54 11011 Hyun jun Lee Korea, (south) republic of 122:40:49 11012 Viggo Fält Team Fält Linköping, Sweden 57:45:24 11013 Richard Fält Team Fält Linköping, Sweden 57:45:28 11014 Rasmus Nummela Rackmannarna Pjelax, Finland 98:59:06 11015 Rafael Nummela Rackmannarna Pjelax, Finland 98:59:06 11017 Marie Zølner Hillerød, Denmark 82:11:49 11018 Niklas Åkesson Mellbystrand, Sweden 99:45:22 11019 Viggo Åkesson Mellbystrand, Sweden 99:45:22 11020 Damian Sulik #StopComplaining Siegen, Germany 101:13:24 11023 Bruno Svendsen Tylstrup, Denmark 74:48:08 11024 Philip Oswald Lakeland, USA 55:52:02 11025 Virginia Marshall Lakefield, Canada 55:57:54 11026 Andreas Mathiasson Backyard Heroes Ödsmål, Sweden 75:12:02 11028 Stine Andersen Brædstrup, Denmark 104:35:37 11030 Patte Johansson Tiger Södertälje, Sweden 80:24:51 11031 Frederic Wiesenbach BB Dahn, Germany 101:21:50 11032 Romea Brugger BB Berlin, Germany 101:22:44 11034 Oliver Freudenberg Heyda, Germany 75:07:48 11035 Jan Hennig Farum, Denmark 82:11:50 11036 Robert Falkenberg Farum, Denmark 82:11:51 11037 Edo Boorsma Sint annaparochie, Netherlands 123:17:34 11038 Trijneke Stuit Sint annaparochie, Netherlands 123:17:35 11040 Sebastian Keck TATSE Gieäen, Germany 104:08:01 11041 Tatjana Kage TATSE Gieäen, Germany 104:08:02 11042 Eun Lee