China's 1823 Flood

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Bibliography [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7220/bibliography-pdf-7220.webp)

Bibliography [PDF]

Bibliography, Ancient TL, Vol. 35, No. 2, 2017 Bibliography _____________________________________________________________________________________________________ Compiled by Sebastien Huot From 15th May 2017 to 1st December 2017 Various geological applications - aeolian Arbogast, A.F., Luehmann, M.D., William Monaghan, G., Lovis, W.A., Wang, H., 2017. Paleoenvironmental and geomorphic significance of bluff-top dunes along the Au Sable River in Northeastern Lower Michigan, USA. Geomorphology 297, 112-121, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2017.09.017. Guedes, C.C.F., Giannini, P.C.F., Sawakuchi, A.O., DeWitt, R., Paulino de Aguiar, V.Â., 2017. Weakening of northeast trade winds during the Heinrich stadial 1 event recorded by dune field stabilization in tropical Brazil. Quaternary Research 88, 369-381, http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/qua.2017.79. Ho, L.-D., Lüthgens, C., Wong, Y.-C., Yen, J.-Y., Chyi, S.-J., 2017. Late Holocene cliff-top dune evolution in the Hengchun Peninsula of Taiwan: Implications for palaeoenvironmental reconstruction. Journal of Asian Earth Sciences 148, 13-30, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jseaes.2017.08.024. Hu, G., Yu, L., Dong, Z., Lu, J., Li, J., Wang, Y., Lai, Z., 2018. Holocene aeolian activity in the Zoige Basin, northeastern Tibetan Plateau, China. Catena 160, 321-328, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2017.10.005. Huntley, D.H., Hickin, A.S., Lian, O.B., 2016. The pattern and style of deglaciation at the Late Wisconsinan Laurentide and Cordilleran ice sheet limits in northeastern British Columbia. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 54, 52-75, http://dx.doi.org/10.1139/cjes-2016-0066. -

A Miraculous Ningguo City of China and Analysis of Influencing Factors of Competitive Advantage

www.ccsenet.org/jgg Journal of Geography and Geology Vol. 3, No. 1; September 2011 A Miraculous Ningguo City of China and Analysis of Influencing Factors of Competitive Advantage Wei Shui Department of Eco-agriculture and Regional Development Sichuan Agricultural University, Chengdu Sichuan 611130, China & School of Geography and Planning Sun Yat-Sen University, Guangzhou 510275, China Tel: 86-158-2803-3646 E-mail: [email protected] Received: March 31, 2011 Accepted: April 14, 2011 doi:10.5539/jgg.v3n1p207 Abstract Ningguo City is a remote and small county in Anhui Province, China. It has created “Ningguo Miracle” since 1990s. Its general economic capacity has been ranked #1 (the first) among all the counties or cities in Anhui Province since 2000. In order to analyze the influencing factors of competitive advantages of Ningguo City and explain “Ningguo Miracle”, this article have evaluated, analyzed and classified the general economic competitiveness of 61 counties (cities) in Anhui Province in 2004, by 14 indexes of evaluation index system. The result showed that compared with other counties (cities) in Anhui Province, Ningguo City has more advantages in competition. The competitive advantage of Ningguo City is due to the productivities, the effect of the second industry and industry, and the investment of fixed assets. Then the influencing factors of Ningguo’s competitiveness in terms of productivity were analyzed with authoritative data since 1990 and a log linear regression model was established by stepwise regression method. The results demonstrated that the key influencing factor of Ningguo City’s competitive advantage was the change of industry structure, especially the change of manufacture structure. -

The Chinese Civil War (1927–37 and 1946–49)

13 CIVIL WAR CASE STUDY 2: THE CHINESE CIVIL WAR (1927–37 AND 1946–49) As you read this chapter you need to focus on the following essay questions: • Analyze the causes of the Chinese Civil War. • To what extent was the communist victory in China due to the use of guerrilla warfare? • In what ways was the Chinese Civil War a revolutionary war? For the first half of the 20th century, China faced political chaos. Following a revolution in 1911, which overthrew the Manchu dynasty, the new Republic failed to take hold and China continued to be exploited by foreign powers, lacking any strong central government. The Chinese Civil War was an attempt by two ideologically opposed forces – the nationalists and the communists – to see who would ultimately be able to restore order and regain central control over China. The struggle between these two forces, which officially started in 1927, was interrupted by the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese war in 1937, but started again in 1946 once the war with Japan was over. The results of this war were to have a major effect not just on China itself, but also on the international stage. Mao Zedong, the communist Timeline of events – 1911–27 victor of the Chinese Civil War. 1911 Double Tenth Revolution and establishment of the Chinese Republic 1912 Dr Sun Yixian becomes Provisional President of the Republic. Guomindang (GMD) formed and wins majority in parliament. Sun resigns and Yuan Shikai declared provisional president 1915 Japan’s Twenty-One Demands. Yuan attempts to become Emperor 1916 Yuan dies/warlord era begins 1917 Sun attempts to set up republic in Guangzhou. -

China's False Allegations of the Use of Biological Weapons by the United

W O R K I N G P A P E R # 7 8 China’s False Allegations of the Use of Biological Weapons by the United States during the Korean War By Milton Leitenberg, March 2016 THE COLD WAR INTERNATIONAL HISTORY PROJECT WORKING PAPER SERIES Christian F. Ostermann, Series Editor This paper is one of a series of Working Papers published by the Cold War International History Project of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, D.C. Established in 1991 by a grant from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Cold War International History Project (CWIHP) disseminates new information and perspectives on the history of the Cold War as it emerges from previously inaccessible sources on “the other side” of the post-World War II superpower rivalry. The project supports the full and prompt release of historical materials by governments on all sides of the Cold War, and seeks to accelerate the process of integrating new sources, materials and perspectives from the former “Communist bloc” with the historiography of the Cold War which has been written over the past few decades largely by Western scholars reliant on Western archival sources. It also seeks to transcend barriers of language, geography, and regional specialization to create new links among scholars interested in Cold War history. Among the activities undertaken by the project to promote this aim are a periodic BULLETIN to disseminate new findings, views, and activities pertaining to Cold War history; a fellowship program for young historians from the former Communist bloc to conduct archival research and study Cold War history in the United States; international scholarly meetings, conferences, and seminars; and publications. -

Imperial China and the West Part I, 1815–1881

China and the Modern World: Imperial China and the West Part I, 1815–1881 The East India Company’s steamship Nemesis and other British ships engaging Chinese junks in the Second Battle of Chuenpi, 7 January 1841, during the first opium war. (British Library) ABOUT THE ARCHIVE China and the Modern World: Imperial China and the West Part I, 1815–1881 is digitised from the FO 17 series of British Foreign Office Files—Foreign Office: Political and Other Departments: General Correspondence before 1906, China— held at the National Archives, UK, providing a vast and significant primary source for researching every aspect of Chinese-British relations during the nineteenth century, ranging from diplomacy to trade, economics, politics, warfare, emigration, translation and law. This first part includes all content from FO 17 volumes 1–872. Source Library Number of Images The National Archives, UK Approximately 532,000 CONTENT From Lord Amherst’s mission at the start of the nineteenth century, through the trading monopoly of the Canton System, and the Opium Wars of 1839–1842 and 1856–1860, Britain and other foreign powers gradually gained commercial, legal, and territorial rights in China. Imperial China and the West provides correspondence from the Factories of Canton (modern Guangzhou) and from the missionaries and diplomats who entered China in the early nineteenth century, as well as from the envoys and missions sent to China from Britain and the later legation and consulates. The documents comprising this collection include communications to and from the British legation, first at Hong Kong and later at Peking, and British consuls at Shanghai, Amoy (Xiamen), Swatow (Shantou), Hankow (Hankou), Newchwang (Yingkou), Chefoo (Yantai), Formosa (Taiwan), and more. -

Feng Guifen and His Contributions to Tax Rationalization in Southern Jiangsu in 1853-74

ß Protecting Regional Interests: Feng Guifen and His Contributions to Tax Rationalization in Southern Jiangsu in 1853-74 Dissertation zur Erlangung der Würde des Doktors der Philosophie der Universität Hamburg vorgelegt von Mingxin Xiong aus Hubei Hamburg 2017 I Angenommen vom Fachbereich Orientalistik (Asien-Afrika-Institut) der Universität Hamburg Erster Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Michael Friedrich Zweiter Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Kai Vogelsang Datum der Disputation: 9.12.2015 II Acknowledgements Firstly, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my advisor Prof. Friedrich for the continuous support of my Ph.D study, for his patience, motivation, and immense knowledge. His guidance helped me throughout researching and writing of this thesis. I could not have imagined having a better advisor and mentor for my Ph.D study. I am deeply indebted to thank my advisor Prof. Zhu Weizheng who passed away three years ago for guiding me into the field of intellectual history and for enlightening me to deal with Feng Guifen study. I would like to thank Prof. Vogelsang, who provided me an opportunity to join his textual criticism work of Jiaobinlu kangyi. My sincere thanks also goes to my friends Yaxinlinglong, Dong Lihui, Yuan Yi, Ma Yunhui, Wang Ying, Daisy Cheung, Li Mengyan, Fu Chong, Yuan Wenjun, Liu Haibin, Alice Chang, Christian Textor, Max Jakob Fölster, Wang Bin, Zhu Wenjin for their kind assistance, encouragement and companionship. Last but not the least, I would like to thank my parents for supporting me spiritually throughout writing this thesis and my life in general. III CONTENTS Introduction .................................................................................................................. 1 CHAPTER ONE: The Grain Tribute Tax in Southern Jiangsu .......................... -

Sino-US Relations and Ulysses S. Grant's Mediation

Looking for a Friend: Sino-U.S. Relations and Ulysses S. Grant’s Mediation in the Ryukyu/Liuqiu 琉球 Dispute of 1879 Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Chad Michael Berry Graduate Program in East Asian Studies The Ohio State University 2014 Thesis Committee: Christopher A. Reed, Advisor Robert J. McMahon Ying Zhang Copyright by Chad Michael Berry 2014 Abstract In March 1879, Japan announced the end of the Ryukyu (Liuqiu) Kingdom and the establishment of Okinawa Prefecture in its place. For the previous 250 years, Ryukyu had been a quasi-independent tribute-sending state to Japan and China. Following the arrival of Western imperialism to East Asia in the 19th century, Japan reacted to the changing international situation by adopting Western legal standards and clarifying its borders in frontier areas such as the Ryukyu Islands. China protested Japanese actions in Ryukyu, though Qing Dynasty (1644-1912) leaders were not willing to go to war over the islands. Instead, Qing leaders such as Li Hongzhang (1823-1901) and Prince Gong (1833-1898) sought to resolve the dispute through diplomatic means, including appeals to international law, rousing global public opinion against Japan, and, most significantly, requesting the mediation of the United States and former U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant (1822-1885). Initially, China hoped Grant’s mediation would lead to a restoration of the previous arrangement of Ryukyu being a dually subordinate kingdom to China and Japan. In later negotiations, China sought a three-way division of the islands among China, Japan, and Ryukyu. -

Dams on the Mekong

Dams on the Mekong A literature review of the politics of water governance influencing the Mekong River Karl-Inge Olufsen Spring 2020 Master thesis in Human geography at the Department of Sociology and Human Geography, Faculty of Social Sciences UNIVERSITY OF OSLO Words: 28,896 08.07.2020 II Dams on the Mekong A literature review of the politics of water governance influencing the Mekong River III © Karl-Inge Olufsen 2020 Dams on the Mekong: A literature review of the politics of water governance influencing the Mekong River Karl-Inge Olufsen http://www.duo.uio.no/ IV Summary This thesis offers a literature review on the evolving human-nature relationship and effect of power struggles through political initiatives in the context of Chinese water governance domestically and on the Mekong River. The literature review covers theoretical debates on scale and socionature, combining them into one framework to understand the construction of the Chinese waterscape and how it influences international governance of the Mekong River. Purposive criterion sampling and complimentary triangulation helped me do rigorous research despite relying on secondary sources. Historical literature review and integrative literature review helped to build an analytical narrative where socionature and scale explained Chinese water governance domestically and on the Mekong River. Through combining the scale and socionature frameworks I was able to build a picture of the hybridization process creating the Chinese waterscape. Through the historical review, I showed how water has played an important part for creating political legitimacy and influencing, and being influenced, by state-led scalar projects. Because of this importance, throughout history the Chinese state has favored large state-led scalar projects for the governance of water. -

9781107069879 Index.Pdf

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-06987-9 — The Qing Empire and the Opium War Mao Haijian , Translated by Joseph Lawson , Peter Lavelle , Craig Smith , Introduction by Julia Lovell Index More Information Index 18th Regiment , 286 , 306 35 – 37 , 45 , 119 – 21 , 122 , 209 ; coastal , 34 , 26th Regiment , 205 , 242 , 286 35 – 36 , 38 , 115 ; concealed , 208 ; early- 37th Regiment , 257 warning , 199 ; fortii ed , vi , 36 , 121 , 209 , 37th Regiment of Madras Native Infantry , 206 218 – 20 , 281 , 493 ; sand- bagged , 210 , 218 , 49th Regiment , 205 , 286 232 , 309 55th Regiment , 286 , 306 Battle at Dinghai, showing the British attacks, 98th Regiment , 384 Qing defensive positions, and the walled town of Dinghai , 305 Ackbar , 385 Battle at Guangzhou, showing British Aigun , 500 attacks , 241 American citizens , 452 , 456 – 58 , 460 , 462 , Battle at Humen, showing the British attacks 463 – 64 , 465 – 68 , 475 , 478 , 511 , 513 and Qing defensive positions , 198 American envoys , 458 – 59 , 461 Battle at Wusong, showing British attacks and American merchants , 96 , 97 – 99 , 152 , 218 , Qing defensive positions , 380 227 , 455 – 57 , 503 Battle at Xiamen, showing main British American ships , 103 , 456 – 57 , 467 attacks and Qing defensive positions , 287 American treaties , 478 Battle at Zhapu, showing Qing defensive Amoy , 427 , 452 positions and British attacks , 376 Anhui , 50 – 51 , 88 , 111 , 163 – 64 , 178 , 324 , 328 , Battle at Zhenhai, showing the Qing defensive 331 , 353 – 54 , 358 positions and British attacks , 311 Ansei -

Settlement Patterns, Chiefdom Variability, and the Development of Early States in North China

JOURNAL OF ANTHROPOLOGICAL ARCHAEOLOGY 15, 237±288 (1996) ARTICLE NO. 0010 Settlement Patterns, Chiefdom Variability, and the Development of Early States in North China LI LIU School of Archaeology, La Trobe University, Melbourne, Australia Received June 12, 1995; revision received May 17, 1996; accepted May 26, 1996 In the third millennium B.C., the Longshan culture in the Central Plains of northern China was the crucial matrix in which the ®rst states evolved from the basis of earlier Neolithic societies. By adopting the theoretical concept of the chiefdom and by employing the methods of settlement archaeology, especially regional settlement hierarchy and rank-size analysis, this paper introduces a new approach to research on the Longshan culture and to inquiring about the development of the early states in China. Three models of regional settlement pattern correlating to different types of chiefdom systems are identi®ed. These are: (1) the centripetal regional system in circumscribed regions representing the most complex chiefdom organizations, (2) the centrifugal regional system in semi-circumscribed regions indicating less integrated chiefdom organization, and (3) the decentral- ized regional system in noncircumscribed regions implying competing and the least complex chief- dom organizations. Both external and internal factors, including geographical condition, climatic ¯uctuation, Yellow River's changing course, population movement, and intergroup con¯ict, played important roles in the development of complex societies in the Longshan culture. As in many cultures in other parts of the world, the early states in China emerged from a system of competing chiefdoms, which was characterized by intensive intergroup con¯ict and frequent shifting of political centers. -

Henan Wastewater Management and Water Supply Sector Project (11 Wastewater Management and Water Supply Subprojects)

Environmental Assessment Report Summary Environmental Impact Assessment Project Number: 34473-01 February 2006 PRC: Henan Wastewater Management and Water Supply Sector Project (11 Wastewater Management and Water Supply Subprojects) Prepared by Henan Provincial Government for the Asian Development Bank (ADB). The summary environmental impact assessment is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 02 February 2006) Currency Unit – yuan (CNY) CNY1.00 = $0.12 $1.00 = CNY8.06 The CNY exchange rate is determined by a floating exchange rate system. In this report a rate of $1.00 = CNY8.27 is used. ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank BOD – biochemical oxygen demand COD – chemical oxygen demand CSC – construction supervision company DI – design institute EIA – environmental impact assessment EIRR – economic internal rate of return EMC – environmental management consultant EMP – environmental management plan EPB – environmental protection bureau GDP – gross domestic product HPG – Henan provincial government HPMO – Henan project management office HPEPB – Henan Provincial Environmental Protection Bureau HRB – Hai River Basin H2S – hydrogen sulfide IA – implementing agency LEPB – local environmental protection bureau N – nitrogen NH3 – ammonia O&G – oil and grease O&M – operation and maintenance P – phosphorus pH – factor of acidity PMO – project management office PM10 – particulate -

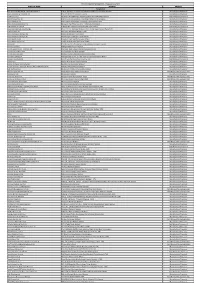

TIER2 SITE NAME ADDRESS PROCESS M Ns Garments Printing & Embroidery

TIER 2 MANUFACTURING SITES - Produced July 2021 TIER2 SITE NAME ADDRESS PROCESS Bangladesh Mns Garments Printing & Embroidery (Unit 2) House 305 Road 34 Hazirpukur Choydana National University Gazipur Manufacturer/Processor (A&E) American & Efird (Bd) Ltd Plot 659 & 660 93 Islampur Gazipur Manufacturer/Processor A G Dresses Ltd Ag Tower Plot 09 Block C Tongi Industrial Area Himardighi Gazipur Next Branded Component Abanti Colour Tex Ltd Plot S A 646 Shashongaon Enayetnagar Fatullah Narayanganj Manufacturer/Processor Aboni Knitwear Ltd Plot 169 171 Tetulzhora Hemayetpur Savar Dhaka 1340 Manufacturer/Processor Afrah Washing Industries Ltd Maizpara Taxi Track Area Pan - 4 Patenga Chottogram Manufacturer/Processor AKM Knit Wear Limited Holding No 14 Gedda Cornopara Ulail Savar Dhaka Next Branded Component Aleya Embroidery & Aleya Design Hose 40 Plot 808 Iqbal Bhaban Dhour Nishat Nagar Turag Dhaka 1230 Manufacturer/Processor Alim Knit (Bd) Ltd Nayapara Kashimpur Gazipur 1750 Manufacturer/Processor Aman Fashions & Designs Ltd Nalam Mirzanagar Asulia Savar Manufacturer/Processor Aman Graphics & Design Ltd Nazimnagar Hemayetpur Savar Dhaka Manufacturer/Processor Aman Sweaters Ltd Rajaghat Road Rajfulbaria Savar Dhaka Manufacturer/Processor Aman Winter Wears Ltd Singair Road Hemayetpur Savar Dhaka Manufacturer/Processor Amann Bd Plot No Rs 2497-98 Tapirbari Tengra Mawna Shreepur Gazipur Next Branded Component Amantex Limited Boiragirchala Sreepur Gazipur Manufacturer/Processor Ananta Apparels Ltd - Adamjee Epz Plot 246 - 249 Adamjee Epz Narayanganj