I.D. Jiangnan 241

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Miraculous Ningguo City of China and Analysis of Influencing Factors of Competitive Advantage

www.ccsenet.org/jgg Journal of Geography and Geology Vol. 3, No. 1; September 2011 A Miraculous Ningguo City of China and Analysis of Influencing Factors of Competitive Advantage Wei Shui Department of Eco-agriculture and Regional Development Sichuan Agricultural University, Chengdu Sichuan 611130, China & School of Geography and Planning Sun Yat-Sen University, Guangzhou 510275, China Tel: 86-158-2803-3646 E-mail: [email protected] Received: March 31, 2011 Accepted: April 14, 2011 doi:10.5539/jgg.v3n1p207 Abstract Ningguo City is a remote and small county in Anhui Province, China. It has created “Ningguo Miracle” since 1990s. Its general economic capacity has been ranked #1 (the first) among all the counties or cities in Anhui Province since 2000. In order to analyze the influencing factors of competitive advantages of Ningguo City and explain “Ningguo Miracle”, this article have evaluated, analyzed and classified the general economic competitiveness of 61 counties (cities) in Anhui Province in 2004, by 14 indexes of evaluation index system. The result showed that compared with other counties (cities) in Anhui Province, Ningguo City has more advantages in competition. The competitive advantage of Ningguo City is due to the productivities, the effect of the second industry and industry, and the investment of fixed assets. Then the influencing factors of Ningguo’s competitiveness in terms of productivity were analyzed with authoritative data since 1990 and a log linear regression model was established by stepwise regression method. The results demonstrated that the key influencing factor of Ningguo City’s competitive advantage was the change of industry structure, especially the change of manufacture structure. -

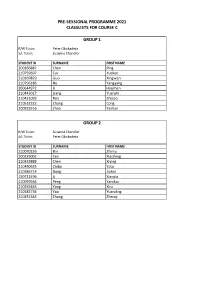

Classlists for C by Group

PRE-SESSIONAL PROGRAMME 2021 CLASSLISTS FOR COURSE C GROUP 1 R/W Tutor: Peter Obukadeta S/L Tutor: Suzanne Chandler STUDENT ID SURNAME FIRST NAME 200166887 Chen Ping 210759697 Cui Yuekun 210169829 Guo Xingwen 210796186 Hu Yangyang 200644972 Li Haozhan 210443017 Liang Yuanzhi 210421093 Ren Zhijiao 210532322 Zhang Cong 200925516 Zhao Yashan GROUP 2 R/W Tutor: Suzanne Chandler S/L Tutor: Peter Obukadeta STUDENT ID SURNAME FIRST NAME 210070226 Bin Zhimu 200329002 Cen Xiaofeng 210333888 Chen Xiying 210450635 Chiba Yota 210386714 Dong Jiahui 190711496 Li Xiaoxia 210059564 Peng Yanduo 210255465 Yang Xiru 210182736 Yao Yuanding 210252383 Zhang Zhenqi GROUP 3 R/W Tutor: Mark Heffernan S/L Tutor: Alan Hart STUDENT ID SURNAME FIRST NAME 210154386 Cai Zhenping 210462580 Ge Xiaodan 210648276 Hirunkhajonrote Kullanut 210182714 Huang Siwei 200141563 Kung Tzu-Ning 200305176 Punsri Punnatorn 200664774 Sayin Humeyra 210186446 Shehata Omar 171003323 Tutberidze Tea 200134624 Wang Shuo 200136019 Xu Ming 200278696 Yan Jiaxin 210357851 Yuan Lai 210029165 Zhang Anru 210219777 Zhang Jiasheng GROUP 4 R/W Tutor: Sherin White S/L Tutor: Alan Hart STUDENT ID SURNAME FIRST NAME 200247588 Chen Chong 200349343 Li Cheng 210622933 Liang Wenxuan 210219618 Liu Huiyuan 210376298 Liu Zeyu 210237531 Mei Lyuke 200132620 Qi Shuyu 210681907 Wang Handuo 200015356 Wu Zhuoyue 200071994 Xie Kaijun GROUP 5 R/W Tutor: Chukwudi Dozie S/L Tutor: Nora Mikso STUDENT ID SURNAME FIRST NAME 210563304 Almalek Ahmed 210186309 Altamimi Saud 210251102 Cheng Han-Yu 210349823 Guo Wenyuan 210239409 -

Download Article

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 341 5th International Conference on Arts, Design and Contemporary Education (ICADCE 2019) Exploring the Influence of Western Modern Composition on Image Oil Painting After "The Fine of 1985" Shisheng Lyu Haiying Liu College of Art and Design College of Art and Design Wuhan Textile University Wuhan Textile University Wuhan, China 430073 Wuhan, China 430073 Abstract—This paper starts with the modern composition in modern composition. They have various painting genres of the West. Through the development of Chinese imagery oil and expressions, enriching the art form of oil painting. painting in China and its influence on Chinese art, this paper explores the influence and development of the post-modern Since the 1980s, with the gradual acceleration of reform composition on China's image oil painting after "The Fine of and opening up, Chinese art has withstood the invasion of 1985". Firstly, it analyzes the historical and cultural foreign cultures and experienced the innovation of cultural background and characteristics of Western modern and artistic thoughts. Image oil paintings have turned their composition. Secondly, it focuses on the development of attention to the exploration of the sense of form of art modern composition in China, and elaborates on the artistic ontology and have made valuable explorations in painting expressions of Chinese image oil painters influenced by form and language of expression, which is largely influenced modern composition. Finally, it considers the main reason why by the form and language of Western modern composition. Chinese image oil painting is influenced by modern Some contemporary oil painters have deeply studied the composition. -

Produzent Adresse Land Allplast Bangladesh Ltd

Zeitraum - Produzenten mit einem Liefertermin zwischen 01.01.2020 und 31.12.2020 Produzent Adresse Land Allplast Bangladesh Ltd. Mulgaon, Kaliganj, Gazipur, Rfl Industrial Park Rip, Mulgaon, Sandanpara, Kaligonj, Gazipur, Dhaka Bangladesh Bengal Plastics Ltd. (Unit - 3) Yearpur, Zirabo Bazar, Savar, Dhaka Bangladesh Durable Plastic Ltd. Mulgaon, Kaligonj, Gazipur, Dhaka Bangladesh HKD International (Cepz) Ltd. Plot # 49-52, Sector # 8, Cepz, Chittagong Bangladesh Lhotse (Bd) Ltd. Plot No. 60 & 61, Sector -3, Karnaphuli Export Processing Zone, North Potenga, Chittagong Bangladesh Plastoflex Doo Branilaca Grada Bb, Gračanica, Federacija Bosne I H Bosnia-Herz. ASF Sporting Goods Co., Ltd. Km 38.5, National Road No. 3, Thlork Village, Chonrok Commune, Konrrg Pisey, Kampong Spueu Cambodia Powerjet Home Product (Cambodia) Co., Ltd. Manhattan (Svay Rieng) Special Economic Zone, National Road 1, Sangkat Bavet, Krong Bavet, Svaay Rieng Cambodia AJS Electronics Ltd. 1st Floor, No. 3 Road 4, Dawei, Xinqiao, Xinqiao Community, Xinqiao Street, Baoan District, Shenzhen, Guangdong China AP Group (China) Co., Ltd. Ap Industry Garden, Quetang East District, Jinjiang, Fujian China Ability Technology (Dong Guan) Co., Ltd. Songbai Road East, Huanan Industrial Area, Liaobu Town, Donggguan, Guangdong China Anhui Goldmen Industry & Trading Co., Ltd. A-14, Zongyang Industrial Park, Tongling, Anhui China Aold Electronic Ltd. Near The Dahou Viaduct, Tianxin Industrial District, Dahou Village, Xiegang Town, Dongguan, Guangdong China Aurolite Electrical (Panyu Guangzhou) Ltd. Jinsheng Road No. 1, Jinhu Industrial Zone, Hualong, Panyu District, Guangzhou, Guangdong China Avita (Wujiang) Co., Ltd. No. 858, Jiaotong Road, Wujiang Economic Development Zone, Suzhou, Jiangsu China Bada Mechanical & Electrical Co., Ltd. No. 8 Yumeng Road, Ruian Economic Development Zone, Ruian, Zhejiang China Betec Group Ltd. -

Anhui Hefei Urban Environment Improvement Project

Major Change in Scope and Implementation Arrangements Project Number: 36595 Loan Number: 2328-PRC May 2009 People's Republic of China: Anhui Hefei Urban Environment Improvement Project CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 12 May 2009) Currency Unit - yuan (CNY) CNY1.00 = $0.1466 $1.00 = CNY6.8230 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank EA – executing agency HMG – Hefei municipal government HUCIC – Hefei Urban Construction Investment Company HXSAOC – Hefei Xincheng State Assets Operating Company Limited IA – implementing agency km – kilometer m3 – cubic meter PMO – project management office WWTP – wastewater treatment plant NOTE In this report, "$" refers to US dollars Vice-President C. Lawrence Greenwood, Jr., Operations Group 2 Director General K. Gerhaeusser, East Asia Department (EARD) Director A. Leung, Urban and Social Sectors Division, EARD Team leader R. Mamatkulov, Urban Development Specialist, EARD Team member C. Navarro, Project Officer (Portfolio Management), EARD In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. CONTENTS Page MAPS I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. BACKGROUND 1 A. Scope of the Project 2 B. Original Cost Estimates and Financing Plan 3 C. Status of Project Implementation 4 III. THE PROPOSED CHANGES 5 A. Change in Project Scope 5 B. Change in Implementation Arrangements 6 C. Reallocation of Loan Proceeds 6 IV. ASSESSMENT 6 V. RECOMMENDATION 7 APPENDIXES 1. Original Design and Monitoring Framework 8 2. Summary Cost Estimates and Financing Plan 12 3. -

Manchurian Incident by Ah Xiang

Manchurian Incident by Ah Xiang Excerpts from “Resistance Wars: 1931-1945” at http://www.republicanchina.org/war.html For updates and related articles, check http://www.republicanchina.org/RepublicanChina-pdf.htm Mukden Incident - 9/18/1931 Japanese militarists had been fomenting calls for war against China throughout 1931. Liu Feng stated that in May 1931, Itagaki Seishiro, a colonel equivalent of Kwantung Army, was responsible for devising the one-night provocation and occupation of major cities. In June, Japanese spies, Nakamura Shintaro and etc, were caught, and later shot dead. At Mt Wanbaoshan, near Changchun, Koreans forcefully dug a ditch for irrigating their fields. One month later, on July 2nd, Japanese police shot dead Chinese peasants who were in conflicts with Korean. Further, Japanese incited massive ethnic cleansing against Chinese on Korean peninsula. Chinese newspaper pointed out that it could very well be the signal portending the start of full Japanese invasion against China. On July 12th, Chiang Kai-shek instructed Zhang Xueliang by stating that "this is not a time for war [against Japan]". To quell Shi Yousan rebellion in Henan Prov, Zhang Xueliang relocated 60,000 more troops to northern China, in addition to 120,000 troops that were steered away on Sept 18th 1930 from Manchuria for the "War of the Central Plains". Beginning from July 1931, Japanese army conducted military exercises without notifying Chinese in advance. Per Bi Wanwen, 2nd column of Shenyang garrison army of Japanese Kwantung Army had shipped over heavy cannons in July in preparation for attacking Shenyang city. Japanese newspaper reported that Japanese infantry ministry chief had called for war against China on Aug 4th 1931. -

EDUCATION in CHINA a Snapshot This Work Is Published Under the Responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD

EDUCATION IN CHINA A Snapshot This work is published under the responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD. The opinions expressed and arguments employed herein do not necessarily reflect the official views of OECD member countries. This document and any map included herein are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. Photo credits: Cover: © EQRoy / Shutterstock.com; © iStock.com/iPandastudio; © astudio / Shutterstock.com Inside: © iStock.com/iPandastudio; © li jianbing / Shutterstock.com; © tangxn / Shutterstock.com; © chuyuss / Shutterstock.com; © astudio / Shutterstock.com; © Frame China / Shutterstock.com © OECD 2016 You can copy, download or print OECD content for your own use, and you can include excerpts from OECD publications, databases and multimedia products in your own documents, presentations, blogs, websites and teaching materials, provided that suitable acknowledgement of OECD as source and copyright owner is given. All requests for public or commercial use and translation rights should be submitted to [email protected]. Requests for permission to photocopy portions of this material for public or commercial use shall be addressed directly to the Copyright Clearance Center (CCC) at [email protected] or the Centre français d’exploitation du droit de copie (CFC) at [email protected]. Education in China A SNAPSHOT Foreword In 2015, three economies in China participated in the OECD Programme for International Student Assessment, or PISA, for the first time: Beijing, a municipality, Jiangsu, a province on the eastern coast of the country, and Guangdong, a southern coastal province. -

China's False Allegations of the Use of Biological Weapons by the United

W O R K I N G P A P E R # 7 8 China’s False Allegations of the Use of Biological Weapons by the United States during the Korean War By Milton Leitenberg, March 2016 THE COLD WAR INTERNATIONAL HISTORY PROJECT WORKING PAPER SERIES Christian F. Ostermann, Series Editor This paper is one of a series of Working Papers published by the Cold War International History Project of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, D.C. Established in 1991 by a grant from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Cold War International History Project (CWIHP) disseminates new information and perspectives on the history of the Cold War as it emerges from previously inaccessible sources on “the other side” of the post-World War II superpower rivalry. The project supports the full and prompt release of historical materials by governments on all sides of the Cold War, and seeks to accelerate the process of integrating new sources, materials and perspectives from the former “Communist bloc” with the historiography of the Cold War which has been written over the past few decades largely by Western scholars reliant on Western archival sources. It also seeks to transcend barriers of language, geography, and regional specialization to create new links among scholars interested in Cold War history. Among the activities undertaken by the project to promote this aim are a periodic BULLETIN to disseminate new findings, views, and activities pertaining to Cold War history; a fellowship program for young historians from the former Communist bloc to conduct archival research and study Cold War history in the United States; international scholarly meetings, conferences, and seminars; and publications. -

Analysis of Character Convergence of Jiangnan Ancient Towns Lei Yunyao , Zhang Qiongfang

International Forum on Management, Education and Information Technology Application (IFMEITA 2016) Analysis of Character Convergence of Jiangnan Ancient Towns Lei Yunyao1, a, Zhang Qiongfang 1,b 1 Wuchang Shouyi University, Wuhan 430064 China [email protected], b [email protected] Key Words:Jiangnan Ancient Towns; Character convergence; Analysis Abstract:This article illustrates the representation of character convergence of Jiangnan Ancient Towns. It analyzes the formation mechanism of character convergence to build the whole image of these ancient towns with Zhouzhuang as a prototype. Based on Tourism Geography Theory and Regional Linkage Theory, it puts forward the fact that the character convergence can be beneficial to building a whole tourism image and to enhancing people’s awareness of ancient heritage. But some problems caused by the convergence will also be presented, such as the identical tourism development model, the backward infrastructure and the destruction of original ecology. Introduction With Taihu Lake as the center, the region of Jiangnan, the south of the lower reaches of the Yangtze River, is scattered all over by many historic ancient towns. These towns have a long history and deep cultural deposit. They are densely occupied and economically developed. They form a national transport network combined with inland waterway. These towns have witnessed a long-term economic prosperity in the south of the lower reaches of the Yangtze River and are now generally called “Jiangnan Ancient Towns”. Since 1980s, under the wave of reform, opening up and modernization construction, experience-based tourism and leisure tourism of these towns have achieved great development. Under the influence of “China's First Water Town” Zhouzhuang, some other similar towns like Tongli, Luzhi, Xitang, Nanxun, Wuzhen all choose to follow suit. -

SGS-Safeguards 04910- Minimum Wages Increased in Jiangsu -EN-10

SAFEGUARDS SGS CONSUMER TESTING SERVICES CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIILITY SOLUTIONS NO. 049/10 MARCH 2010 MINIMUM WAGES INCREASED IN JIANGSU Jiangsu becomes the first province to raise minimum wages in China in 2010, with an average increase of over 12% effective from 1 February 2010. Since 2008, many local governments have deferred the plan of adjusting minimum wages due to the financial crisis. As economic results are improving, the government of Jiangsu Province has decided to raise the minimum wages. On January 23, 2010, the Department of Human Resources and Social Security of Jiangsu Province declared that the minimum wages in Jiangsu Province would be increased from February 1, 2010 according to Interim Provisions on Minimum Wages of Enterprises in Jiangsu Province and Minimum Wages Standard issued by the central government. Adjustment of minimum wages in Jiangsu Province The minimum wages do not include: Adjusted minimum wages: • Overtime payment; • Monthly minimum wages: • Allowances given for the Areas under the first category (please refer to the table on next page): middle shift, night shift, and 960 yuan/month; work in particular environments Areas under the second category: 790 yuan/month; such as high or low Areas under the third category: 670 yuan/month temperature, underground • Hourly minimum wages: operations, toxicity and other Areas under the first category: 7.8 yuan/hour; potentially harmful Areas under the second category: 6.4 yuan/hour; environments; Areas under the third category: 5.4 yuan/hour. • The welfare prescribed in the laws and regulations. CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIILITY SOLUTIONS NO. 049/10 MARCH 2010 P.2 Hourly minimum wages are calculated on the basis of the announced monthly minimum wages, taking into account: • The basic pension insurance premiums and the basic medical insurance premiums that shall be paid by the employers. -

French Names Noeline Bridge

names collated:Chinese personal names and 100 surnames.qxd 29/09/2006 13:00 Page 8 The hundred surnames Pinyin Hanzi (simplified) Wade Giles Other forms Well-known names Pinyin Hanzi (simplified) Wade Giles Other forms Well-known names Zang Tsang Zang Lin Zhu Chu Gee Zhu Yuanzhang, Zhu Xi Zeng Tseng Tsang, Zeng Cai, Zeng Gong Zhu Chu Zhu Danian Dong, Zhu Chu Zhu Zhishan, Zhu Weihao Jeng Zhu Chu Zhu jin, Zhu Sheng Zha Cha Zha Yihuang, Zhuang Chuang Zhuang Zhou, Zhuang Zi Zha Shenxing Zhuansun Chuansun Zhuansun Shi Zhai Chai Zhai Jin, Zhai Shan Zhuge Chuko Zhuge Liang, Zhan Chan Zhan Ruoshui Zhuge Kongming Zhan Chan Chaim Zhan Xiyuan Zhuo Cho Zhuo Mao Zhang Chang Zhang Yuxi Zi Tzu Zi Rudao Zhang Chang Cheung, Zhang Heng, Ziche Tzuch’e Ziche Zhongxing Chiang Zhang Chunqiao Zong Tsung Tsung, Zong Xihua, Zhang Chang Zhang Shengyi, Dung Zong Yuanding Zhang Xuecheng Zongzheng Tsungcheng Zongzheng Zhensun Zhangsun Changsun Zhangsun Wuji Zou Tsou Zou Yang, Zou Liang, Zhao Chao Chew, Zhao Kuangyin, Zou Yan Chieu, Zhao Mingcheng Zu Tsu Zu Chongzhi Chiu Zuo Tso Zuo Si Zhen Chen Zhen Hui, Zhen Yong Zuoqiu Tsoch’iu Zuoqiu Ming Zheng Cheng Cheng, Zheng Qiao, Zheng He, Chung Zheng Banqiao The hundred surnames is one of the most popular reference Zhi Chih Zhi Dake, Zhi Shucai sources for the Han surnames. It was originally compiled by an Zhong Chung Zhong Heqing unknown author in the 10th century and later recompiled many Zhong Chung Zhong Shensi times. The current widely used version includes 503 surnames. Zhong Chung Zhong Sicheng, Zhong Xing The Pinyin index of the 503 Chinese surnames provides an access Zhongli Chungli Zhongli Zi to this great work for Western people. -

Imperial China and the West Part I, 1815–1881

China and the Modern World: Imperial China and the West Part I, 1815–1881 The East India Company’s steamship Nemesis and other British ships engaging Chinese junks in the Second Battle of Chuenpi, 7 January 1841, during the first opium war. (British Library) ABOUT THE ARCHIVE China and the Modern World: Imperial China and the West Part I, 1815–1881 is digitised from the FO 17 series of British Foreign Office Files—Foreign Office: Political and Other Departments: General Correspondence before 1906, China— held at the National Archives, UK, providing a vast and significant primary source for researching every aspect of Chinese-British relations during the nineteenth century, ranging from diplomacy to trade, economics, politics, warfare, emigration, translation and law. This first part includes all content from FO 17 volumes 1–872. Source Library Number of Images The National Archives, UK Approximately 532,000 CONTENT From Lord Amherst’s mission at the start of the nineteenth century, through the trading monopoly of the Canton System, and the Opium Wars of 1839–1842 and 1856–1860, Britain and other foreign powers gradually gained commercial, legal, and territorial rights in China. Imperial China and the West provides correspondence from the Factories of Canton (modern Guangzhou) and from the missionaries and diplomats who entered China in the early nineteenth century, as well as from the envoys and missions sent to China from Britain and the later legation and consulates. The documents comprising this collection include communications to and from the British legation, first at Hong Kong and later at Peking, and British consuls at Shanghai, Amoy (Xiamen), Swatow (Shantou), Hankow (Hankou), Newchwang (Yingkou), Chefoo (Yantai), Formosa (Taiwan), and more.