China – Guangzhou – Christians – Local Officials

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

COVID-19 Risk Assessment: Contributing to Maintaining Urban Public Health Security and Achieving Sustainable Urban Development

sustainability Article COVID-19 Risk Assessment: Contributing to Maintaining Urban Public Health Security and Achieving Sustainable Urban Development Jun Zhang * and Xiaodie Yuan School of Architecture and Planning, Yunnan University, Kunming 650500, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: As the most infectious disease in 2020, COVID-19 is an enormous shock to urban public health security and to urban sustainable development. Although the epidemic in China has been brought into control at present, the prevention and control of it is still the top priority of maintaining public health security. Therefore, the accurate assessment of epidemic risk is of great importance to the prevention and control even to overcoming of COVID-19. Using the fused data obtained from fusing multi-source big data such as POI (Point of Interest) data and Tencent-Yichuxing data, this study assesses and analyzes the epidemic risk and main factors that affect the distribution of COVID-19 on the basis of combining with logistic regression model and geodetector model. What’s more, the following main conclusions are obtained: the high-risk areas of the epidemic are mainly concentrated in the areas with relatively dense permanent population and floating population, which means that the permanent population and floating population are the main factors affecting the risk level of the epidemic. In other words, the reasonable control of population density is greatly Citation: Zhang, J.; Yuan, X. conducive to reducing the risk level of the epidemic. Therefore, the control of regional population COVID-19 Risk Assessment: density remains the key to epidemic prevention and control, and home isolation is also the best Contributing to Maintaining Urban means of prevention and control. -

Baiyun Sub-‐District Community Web Information

Baiyun Sub-district Community Web Information Community Name: Baiyun Sub-district,Yuexiu District, Guangzhou City Country : P.R.CHINA Community Population: 51173 Program Start Date:10 July 2013 International Safe Communities Network Member ID: Designation Date: Name of International Safe Communities Support Center: China Occupational Safety and Health Association(COSHA) Certifier : Guldbrand Skjönberg Co-certifier: Report Website: Contact Details: Name: XiaoDong Deng Organization: Baiyun Sub-district Office,Yuexiu District, Guangzhou City Address: NO.38-1 Baiyun Road, Yuexiu District, Guangzhou City, Guangdong Province, P.R.CHINA. Postal Code: 510100 City/ Province: Guangzhou City,Guangdong Province Country: CHINA Phone: 86-20-83744285 Fax: 86-20-83744285 E-mail: [email protected] Community Website: http://styleking.21b.chengxinwujinpifa.com 1 Safety Promotion and Injuries Intervention Program Described by Age Groups Children (0 -14) 1、 Campus Environment Reconstruction lnstall anti-pinch protection devices, add protective pads against injury to sports equipment and alter platform steps, edges of stairs and guardrails to with round corners;Put on warning signs on slippery places in campus; 2、Campus Emergency Safety Program Organize all kinds of emergency evacuation drills and launch safety education campaigns; 3、“The Healthy Growth of Teenagers” Programs 1)“Future Stars”Teenagers Growth Plan (provide services including learning stress relieving, interest cultivation, interpersonal relationship establishment assistances and etc.; 2)Using -

ATTACHMENT 1 Barcode:3800584-02 C-570-107 INV - Investigation

ATTACHMENT 1 Barcode:3800584-02 C-570-107 INV - Investigation - Chinese Producers of Wooden Cabinets and Vanities Company Name Company Information Company Name: A Shipping A Shipping Street Address: Room 1102, No. 288 Building No 4., Wuhua Road, Hongkou City: Shanghai Company Name: AA Cabinetry AA Cabinetry Street Address: Fanzhong Road Minzhong Town City: Zhongshan Company Name: Achiever Import and Export Co., Ltd. Street Address: No. 103 Taihe Road Gaoming Achiever Import And Export Co., City: Foshan Ltd. Country: PRC Phone: 0757-88828138 Company Name: Adornus Cabinetry Street Address: No.1 Man Xing Road Adornus Cabinetry City: Manshan Town, Lingang District Country: PRC Company Name: Aershin Cabinet Street Address: No.88 Xingyuan Avenue City: Rugao Aershin Cabinet Province/State: Jiangsu Country: PRC Phone: 13801858741 Website: http://www.aershin.com/i14470-m28456.htmIS Company Name: Air Sea Transport Street Address: 10F No. 71, Sung Chiang Road Air Sea Transport City: Taipei Country: Taiwan Company Name: All Ways Forwarding (PRe) Co., Ltd. Street Address: No. 268 South Zhongshan Rd. All Ways Forwarding (China) Co., City: Huangpu Ltd. Zip Code: 200010 Country: PRC Company Name: All Ways Logistics International (Asia Pacific) LLC. Street Address: Room 1106, No. 969 South, Zhongshan Road All Ways Logisitcs Asia City: Shanghai Country: PRC Company Name: Allan Street Address: No.188, Fengtai Road City: Hefei Allan Province/State: Anhui Zip Code: 23041 Country: PRC Company Name: Alliance Asia Co Lim Street Address: 2176 Rm100710 F Ho King Ctr No 2 6 Fa Yuen Street Alliance Asia Co Li City: Mongkok Country: PRC Company Name: ALMI Shipping and Logistics Street Address: Room 601 No. -

Assessment of Spatial Accessibility to Residential Care Facilities in 2020 in Guangzhou by Small-Scale Residential Community Data

sustainability Article Assessment of Spatial Accessibility to Residential Care Facilities in 2020 in Guangzhou by Small-Scale Residential Community Data Danni Wang 1,2, Changjian Qiao 3, Sijie Liu 4, Chongyang Wang 2,5,* , Ji Yang 2,5, Yong Li 2,5 and Peng Huang 6 1 Department of Resources and the Urban Planning, Xin Hua College of Sun Yat-Sen University, Guangzhou 510520, China; [email protected] 2 Southern Marine Science and Engineering Guangdong Laboratory (Guangzhou), Guangzhou 511458, China; [email protected] (J.Y.); [email protected] (Y.L.) 3 College of Resources and Environment, Academician Workstation for Urban-Rural Spatial Data Mining, Henan University of Economics and Law, Zhengzhou 450046, China; [email protected] 4 Land and Resources Technology Center of Guangdong Province, Guangzhou 510075, China; [email protected] 5 Key Lab of Guangdong for Utilization of Remote Sensing and Geographical Information System, Guangdong Open Laboratory of Geospatial Information Technology and Application, Guangzhou Institute of Geography, Guangzhou 510070, China 6 Shenzhen Municipal Planning and Natural Resources Bureau-Bao’an Management Bureau, Shenzhen 518101, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-188-0208-0904 Received: 27 February 2020; Accepted: 12 April 2020; Published: 15 April 2020 Abstract: Population aging has increasingly challenged socio-economic development worldwide, highlighting the significance of relevant research such as accessibility to residential care facilities (RCFs). However, a number of previous studies are carried out only on street (town)-to-district scales, which could cause errors of the accessibility to RCFs for a family. In order to improve the resolution to individual families, we measure and compare the accessibilities to RCFs based on 3494 residential communities and 169 streets of Guangzhou in 2020 through the two-step floating catchment area (2SFCA) method. -

Responses to Information Requests

RIR Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada www.irb-cisr.gc.ca Français Home Contact Us Help Search canada.gc.ca Home > Research > Responses to Information Requests RESPONSES TO INFORMATION REQUESTS (RIRs) New Search | About RIR's | Help 07 September 2005 CHN100387.E China: Situation of Protestants and treatment by authorities, particularly in Fujian and Guangdong (2001-2005) Research Directorate, Immigration and Refugee Board, Ottawa General Information Estimates of the number of Protestants in China vary among sources consulted by the Research Directorate. The Chinese government claims that there are more than 15 million adherents of the official Protestant Three-Self Patriotic Movement, although Protestant church officials put the number of worshippers who attend registered churches at 20 million (International Religious Freedom Report 2004 15 Sept. 2004). Estimates of the number of Protestants who belong to "unregistered" church groups range from 30 million to 50 million (Christian Science Monitor 8 Mar. 2004; U.S. News & World Report 30 Apr. 2001; see also International Religious Freedom Report 2004 15 Sept. 2004, Sec. 1). Some academics place the total number of Protestants in China at 90 million (ibid.). Sources agree that the number of Protestants is growing (ibid.; Christian Science Monitor 24 Dec. 2003; Economist 21 Apr. 2005), particularly among urban intellectuals, business people and university students (ibid.; Washington Post 24 Dec. 2002). Henan, the "Bethlehem" of China (Christian Science Monitor 8 Mar. 2004), reportedly has the largest number of Christians among all the provinces of China, with about five million worshippers, most of whom attend "house" churches (SCMP 9 Jan. 2002; see also U.S. -

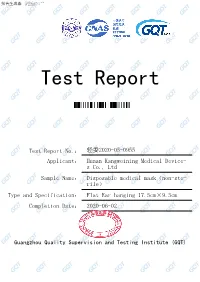

Test Report Guangzhou Quality Supervision and Testing Institute

Test Report Test Report No.: 轻委2020-05-0955 Applicant: Hunan Kangweining Medical Device- s Co., Ltd Sample Name: Disposable medical mask(non-ste- rile) Type and Specification: Flat Ear hanging 17.5cm×9.5cm Completion Date: 2020-06-02 Guangzhou Quality Supervision and Testing Institute (GQT) Important Statement 1. Guangzhou Quality Supervision and Testing Institute (GQT) is the products quality super- vision and testing organization that is set up by the Government and in charge by Guangzhou Administration for Market Regulation. GQT is a social public welfare institution that pro- viding technical support for the government to strengthen the market supervision and ad- ministration, and also accepting commissioned inspection. 2. GQT and the National Quality Supervision and Testing center (center) and the Products Quality Supervision and Testing Station (station) guarantee that the inspection is scien- tific, impartial and accurate and are responsible for the testing result and also keep con- fidentiality of the samples and technical information provided by the applicants. 3. Any report without the signatures of the tester, checker and approver, or altered, or without the special chapter for Inspection and Testing of the Institute (center/station), or without the special testing seal , will be taken as invalid. The test shall not be par- tial copied, picked up and tampered without the authorization of GQT (Center/ Station). 4. The entrusted testing is only valid to the provided samples.The applicant shall not use the inspection results without authorization of GQT (Center/ Station) for undue publicity. 5. The sample and relevant information provided by the applicant, GQT (Center/Station)is not responsible for its authenticity and integrity. -

Shop Direct Factory List Dec 18

Factory Factory Address Country Sector FTE No. workers % Male % Female ESSENTIAL CLOTHING LTD Akulichala, Sakashhor, Maddha Para, Kaliakor, Gazipur, Bangladesh BANGLADESH Garments 669 55% 45% NANTONG AIKE GARMENTS COMPANY LTD Group 14, Huanchi Village, Jiangan Town, Rugao City, Jaingsu Province, China CHINA Garments 159 22% 78% DEEKAY KNITWEARS LTD SF No. 229, Karaipudhur, Arulpuram, Palladam Road, Tirupur, 641605, Tamil Nadu, India INDIA Garments 129 57% 43% HD4U No. 8, Yijiang Road, Lianhang Economic Development Zone, Haining CHINA Home Textiles 98 45% 55% AIRSPRUNG BEDS LTD Canal Road, Canal Road Industrial Estate, Trowbridge, Wiltshire, BA14 8RQ, United Kingdom UK Furniture 398 83% 17% ASIAN LEATHERS LIMITED Asian House, E. M. Bypass, Kasba, Kolkata, 700017, India INDIA Accessories 978 77% 23% AMAN KNITTINGS LIMITED Nazimnagar, Hemayetpur, Savar, Dhaka, Bangladesh BANGLADESH Garments 1708 60% 30% V K FASHION LTD formerly STYLEWISE LTD Unit 5, 99 Bridge Road, Leicester, LE5 3LD, United Kingdom UK Garments 51 43% 57% AMAN GRAPHIC & DESIGN LTD. Najim Nagar, Hemayetpur, Savar, Dhaka, Bangladesh BANGLADESH Garments 3260 40% 60% WENZHOU SUNRISE INDUSTRIAL CO., LTD. Floor 2, 1 Building Qiangqiang Group, Shanghui Industrial Zone, Louqiao Street, Ouhai, Wenzhou, Zhejiang Province, China CHINA Accessories 716 58% 42% AMAZING EXPORTS CORPORATION - UNIT I Sf No. 105, Valayankadu, P. Vadugapal Ayam Post, Dharapuram Road, Palladam, 541664, India INDIA Garments 490 53% 47% ANDRA JEWELS LTD 7 Clive Avenue, Hastings, East Sussex, TN35 5LD, United Kingdom UK Accessories 68 CAVENDISH UPHOLSTERY LIMITED Mayfield Mill, Briercliffe Road, Chorley Lancashire PR6 0DA, United Kingdom UK Furniture 33 66% 34% FUZHOU BEST ART & CRAFTS CO., LTD No. 3 Building, Lifu Plastic, Nanshanyang Industrial Zone, Baisha Town, Minhou, Fuzhou, China CHINA Homewares 44 41% 59% HUAHONG HOLDING GROUP No. -

Qin2020.Pdf (1.836Mb)

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. THE EVOLUTION OF EVANGELICAL SOCIO-POLITICAL APPROACHES IN CONTEMPORARY CHINA (1980S-2010S) Daniel Qin Doctor of Philosophy The University of Edinburgh 2019 DECLARATION I confirm that this thesis presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, has i) been composed entirely by myself ii) been solely the result of my own work iii) not been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification A revised version of chapter II is forthcoming in 2020 in Studies in World Christianity as ‘Samuel Lamb’s Exhortation Regarding Eternal Rewards: A Socio- Political Perspective.’ Daniel Qin _________ Date: ABSTRACT This thesis explores the evolution of Evangelical socio-political approaches in contemporary China, arguing that Evangelicals in both the Three-Self church and the house churches have moved towards an increasing sense of social concern in the period from the 1980s to the 2010s. -

Neregistrované Protestantské Církve V Číně

Masarykova univerzita Filozofická fakulta Ústav religionistiky Religionistika Tereza Hejlová Neregistrované protestantské církve v Číně Bakalářská diplomová práce Vedoucí práce: doc. PhDr. Luboš Bělka, CSc. 2009 Prohlašuji, že jsem diplomovou práci vypracovala samostatně s využitím uvedených pramenů a literatury. V Brně 18. 12. 2009 ………………………………. 2 Na tomto místě bych chtěla poděkovat svému vedoucímu za trpělivost, přínosné podněty a pomoc při psaní práce. 3 Obsah 1. Úvod………………………………………………………………………………str. 5 2. Protestantismus v Číně…………………………………………………………..str. 7 3. Počátky protestantismu v Číně………………………………………………….str. 8 4. Protestantismus pod komunistickou vládou………………………………….str. 11 4.1 Vznik Vlasteneckého hnutí trojí samostatnosti………………………..……str. 12 4.2 Kulturní revoluce………………………………………………………........str. 14 5. Období po Kulturní revoluci…………………………………………………..str. 15 5.1 „Dokument 19“ a 36. článek ústavy…………………………………….......str. 16 5.2 Amity Foundation…………………………………………………………...str. 17 6. Důvody podzemních církví k odmítnutí registrace…………………………..str. 18 7. Perzekuce a pronásledování neregistrovaných církví………………………..str. 20 8. Situace od 90. let 20. století…………………………………………………….str. 21 8.1 The Shouters…………………………………………………………….......str. 22 8.2 Born Again Movement………………………………………………….......str. 22 8.3 Eastern Lightning……………………………………………………………str. 23 8.4 Reakce čínské vlády………………………………………………………...str. 25 9. Problematika statistiky počtu protestantů v Číně……………………………str. 26 10. Hnutí Zpět do Jeruzaléma……………………………………………………str. 28 10.1 Hlavní myšlenka…………………………………………………………...str. -

Study of Heritage Conservation in Guangzhou

Study of Heritage Conservation in Guangzhou Shamian Historic Buildings The Shamian Historic Buildings are a cluster of Western-style buildings constructed by countries such as Britain and France inside the foreign concessions of Guangzhou. These buildings were originally consulates, churches, banks, post offices, telegram offices, firms, hospitals, hotels and residences. The residents at that time were mostly the staff members of the consulates, banks and foreign firms, as well as foreign tax officers and missionaries. The main architectural styles included the British and French colonialist, eclectic and early modernist style. This group of buildings was declared as the first batch of the “National Excellence Modern Building Unit” ( 全國近代優秀建築單位), and was declared a protected site for its historical and cultural value at the national level in 1990 and 1996 respectively. At present these buildings have been progressively adaptively re-used. For instance, the Pallonjee House in South Shamian Street was originally the staff quarters of the Hong Kong & Shanghai Bank, and it is now used as the office of the “Mo Bo-zhi Architectural Firm” (莫伯治建築師事務所). References: 1. Guangzhou Municipal Construction Committee (ed.).《廣州歷史文化名勝》. Guangzhou Municipality: Hua Cheng Publishing Ltd: 2002, pp.141, 144. 2. Guangdong Cultural Website, 荔 灣 區:沙 面 西 式 建 築 . http://www.gdwh.com.cn/xiuxian/2010/0525/article_111.htm 3. Guangzhou Cultural Information Website,沙面建築群. http://www.gzwh.gov.cn/whw/channel/whmc/lsjq/smjzq/index.htm The Shamian Historic Buildings with their continental European The words “PALLONJEE HOUSE” are inscribed on the granite Source of photos: Commissioner of Heritage’s ambience. at the front door of Pallonjee House. -

China – Guangdong – Protestants – Catholics – Underground Churches

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: CHN30006 Country: China Date: 14 March 2006 Keywords: China – Guangdong – Protestants – Catholics – Underground Churches This response was prepared by the Country Research Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. Questions 1. What was the situation for the Protestant underground church in Guangdong from 1990 to March 1998? 2. What was the situation for the Catholic underground church in Guangdong from 1990 to March 1998? 3. What is the position nowadays for both churches? List of Sources Consulted Internet Sources: Government Information & Reports United Nations (UN) Non-Government Organisations International News & Politics Region Specific Links Topic Specific Links Search Engines Google search engine http://www.google.com.au/ Online Subscription Services Library Networks University Sites Databases: Public FACTIVA Reuters Business Briefing DIMIA BACIS Country Information REFINFO IRBDC Research Responses (Canada) RRT ISYS RRT Country Research database, including Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, US Department of State Country Reports on Human Rights Practices. RRT Library FIRST RRT Library Catalogue RESPONSE 1. What was the situation for the Protestant underground church in Guangdong from 1990 to March 1998? 2. What was the situation for the Catholic underground church in Guangdong from 1990 to March 1998? No detailed analysis on the situation of Protestants or Catholics in Guangdong Province was found among the sources consulted. The following reports provide some useful material, although some contradict each other. -

For at Least 2,200 Years, Guangzhou Has Always Been Seen As a City That

South Asian Journal of Tourism and Heritage (2008), Vol. 1, No. 1 Issues for Developing National Heritage Protection Areas for Tourism: A Case study from China HILARY DU CROS Hilary du Cros, Professor, Institute for Tourism Studies, Macao SAR, China ABSTRACT Shamian Island is a nineteenth century European designed historical precinct in Guangzhou, which is also one of the oldest cities in China that has always been a key point for trade and communication. Steamships in the nineteenth century use to bring Western tourists to the city and more lately it has developed a reputation for business and heritage tourism. The Island has continued into the twenty-first century to be a focal point for these visitors. A longitudinal study has been conducted over the last six years that applies the indicators from Butler’s Tourism Area Life Cycle model (1980, 2006) to examine the key issues in its development as a cultural tourism product area. Visits were undertaken annually where observations were made of changes in land use, conservation of heritage assets and tourism development. Interviews were conducted with key stakeholders regarding tourism development and heritage management issues. It was found that the area shows some unexpected characteristics in its development, due to the nature of its protection and management. KEYWORDS: Heritage tourism, tourism product areas, heritage management, China INTRODUCTION Cultural tourism can be defined as, “a form of tourism that relies on a destination's cultural heritage assets and transforms them into products that can be consumed by tourists,” (McKercher and du Cros, 2002:6). Christou (2005) notes that the term “cultural tourism” is used interchangeably with that of “heritage tourism”, which while this is true, is ignoring the fact that the latter really fits neatly within the former.