China – Guangdong – Protestants – Catholics – Underground Churches

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix 1: Rank of China's 338 Prefecture-Level Cities

Appendix 1: Rank of China’s 338 Prefecture-Level Cities © The Author(s) 2018 149 Y. Zheng, K. Deng, State Failure and Distorted Urbanisation in Post-Mao’s China, 1993–2012, Palgrave Studies in Economic History, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92168-6 150 First-tier cities (4) Beijing Shanghai Guangzhou Shenzhen First-tier cities-to-be (15) Chengdu Hangzhou Wuhan Nanjing Chongqing Tianjin Suzhou苏州 Appendix Rank 1: of China’s 338 Prefecture-Level Cities Xi’an Changsha Shenyang Qingdao Zhengzhou Dalian Dongguan Ningbo Second-tier cities (30) Xiamen Fuzhou福州 Wuxi Hefei Kunming Harbin Jinan Foshan Changchun Wenzhou Shijiazhuang Nanning Changzhou Quanzhou Nanchang Guiyang Taiyuan Jinhua Zhuhai Huizhou Xuzhou Yantai Jiaxing Nantong Urumqi Shaoxing Zhongshan Taizhou Lanzhou Haikou Third-tier cities (70) Weifang Baoding Zhenjiang Yangzhou Guilin Tangshan Sanya Huhehot Langfang Luoyang Weihai Yangcheng Linyi Jiangmen Taizhou Zhangzhou Handan Jining Wuhu Zibo Yinchuan Liuzhou Mianyang Zhanjiang Anshan Huzhou Shantou Nanping Ganzhou Daqing Yichang Baotou Xianyang Qinhuangdao Lianyungang Zhuzhou Putian Jilin Huai’an Zhaoqing Ningde Hengyang Dandong Lijiang Jieyang Sanming Zhoushan Xiaogan Qiqihar Jiujiang Longyan Cangzhou Fushun Xiangyang Shangrao Yingkou Bengbu Lishui Yueyang Qingyuan Jingzhou Taian Quzhou Panjin Dongying Nanyang Ma’anshan Nanchong Xining Yanbian prefecture Fourth-tier cities (90) Leshan Xiangtan Zunyi Suqian Xinxiang Xinyang Chuzhou Jinzhou Chaozhou Huanggang Kaifeng Deyang Dezhou Meizhou Ordos Xingtai Maoming Jingdezhen Shaoguan -

Complicated HCV Subtype Expansion Among Drug Users in Guangdong

Infection, Genetics and Evolution 73 (2019) 139–145 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Infection, Genetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/meegid Research paper Complicated HCV subtype expansion among drug users in Guangdong province, China T ⁎ Jin Yana, , Xiao-Bing Fua, Ping-Ping Zhoub, Xiang Heb, Jun Liua, Xu-He Huangb, Guo-Long Yua, Xin-Ge Yana, Jian-Rong Lia, Yan Lia, Peng Lina a Guangdong Provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 160 Qunxian Road, Panyu District, Guangzhou 511430, Guangdong, China b Guangdong Provincial Institute of Public Health, Guangdong Provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 160 Qunxian Road, Panyu District, Guangzhou 511430, Guangdong, China ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Guangdong Province is one of the most developed and populous provinces in southern China. The subtype HCV situation of hepatitis C virus (HCV) in Guangdong remains unknown. The aim of this study was to investigate Subtype and estimate the HCV subtypes in drug users (DU) using a city-based sampling strategy to better understand the Drug users characteristics of HCV transmission in Guangdong. Archived plasma samples (n = 1074) from DU who were Molecular epidemiology anti-HCV positive in 2014 were selected randomly from 20 cities in Guangdong Province. Subtypes were de- Guangdong termined based on core and/or E1 sequences using phylogenetic analysis. The distributions of HCV subtypes in DU and different regions were analyzed. A total of 8 genotypes were identified. The three main HCV subtypes in DU in Guangdong were 6a (63.0%), 3a (15.2%), and 3b (11.8%). Significant differences were discovered among different registered residency and regions but not among genders, marital status, education level, or drug use patterns. -

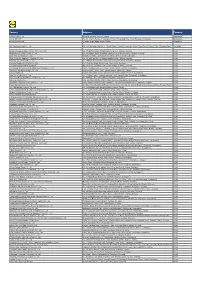

ATTACHMENT 1 Barcode:3800584-02 C-570-107 INV - Investigation

ATTACHMENT 1 Barcode:3800584-02 C-570-107 INV - Investigation - Chinese Producers of Wooden Cabinets and Vanities Company Name Company Information Company Name: A Shipping A Shipping Street Address: Room 1102, No. 288 Building No 4., Wuhua Road, Hongkou City: Shanghai Company Name: AA Cabinetry AA Cabinetry Street Address: Fanzhong Road Minzhong Town City: Zhongshan Company Name: Achiever Import and Export Co., Ltd. Street Address: No. 103 Taihe Road Gaoming Achiever Import And Export Co., City: Foshan Ltd. Country: PRC Phone: 0757-88828138 Company Name: Adornus Cabinetry Street Address: No.1 Man Xing Road Adornus Cabinetry City: Manshan Town, Lingang District Country: PRC Company Name: Aershin Cabinet Street Address: No.88 Xingyuan Avenue City: Rugao Aershin Cabinet Province/State: Jiangsu Country: PRC Phone: 13801858741 Website: http://www.aershin.com/i14470-m28456.htmIS Company Name: Air Sea Transport Street Address: 10F No. 71, Sung Chiang Road Air Sea Transport City: Taipei Country: Taiwan Company Name: All Ways Forwarding (PRe) Co., Ltd. Street Address: No. 268 South Zhongshan Rd. All Ways Forwarding (China) Co., City: Huangpu Ltd. Zip Code: 200010 Country: PRC Company Name: All Ways Logistics International (Asia Pacific) LLC. Street Address: Room 1106, No. 969 South, Zhongshan Road All Ways Logisitcs Asia City: Shanghai Country: PRC Company Name: Allan Street Address: No.188, Fengtai Road City: Hefei Allan Province/State: Anhui Zip Code: 23041 Country: PRC Company Name: Alliance Asia Co Lim Street Address: 2176 Rm100710 F Ho King Ctr No 2 6 Fa Yuen Street Alliance Asia Co Li City: Mongkok Country: PRC Company Name: ALMI Shipping and Logistics Street Address: Room 601 No. -

Mat Lion Dance” in Meizhou

Creative Arts Educ Ther (2019) 5(2):85–95 DOI: 10.15212/CAET/2019/5/25 A Brief Analysis of the Buddhist Implication and Connotation of the “Mat Lion Dance” in Meizhou 浅谈梅州“席狮舞”中的审美意蕴及内涵 Shijie Liu1 and Yuelong Zhang2 1Shenzhen Huafeng Culture Media Co., China 2Department of Dance, Faculty of Dance, Shenzhen University, China Abstract The “Mat Lion Dance” is one of the unique events of the “XiangHua” (which means fragrant flowers in Chinese) Buddhism ritual in Meizhou Hakka, Guangdong, China. From the perspec- tive of aesthetics, the current study will analyze and discuss its cultural background and history as well as its artistic expression and intrinsic value. The article will emphasize three aspects: the relationship between the Hakka and Buddhist cultures; the implications of the performance and process of the Mat Lion Dance; and the function of praying, uniting the clan, and blessing of the Mat Lion Dance. The aim of the article is to deepen public understanding of the Mat Lion Dance, a precious intangible cultural heritage, and enable it to be better protected and inherited. Keywords: Kejia people, Meizhou, Buddhist ceremony, Mat Lion Dance 摘要 “席狮舞”为广东梅州客家“香花”佛事中独有的项目之一,根据现有资料,“席狮 舞”在50年代初之前一直在民间发展传承,作为一项客家佛教仪式流传于民间,并于 2008年被列入第二批国家级非物质文化遗产保护名录。由于梅州特殊的地理人文环 境,以及当地客家人民文化与佛教文化的互相交融,形成了独特的“香花”佛仪,而“ 席狮舞”作为“香花”佛事中的一部分,同样具有它独特且不可替代的作用。本文正是 通过了解分析“席狮舞”的舞蹈形态与过程,进而探究“香花”佛事中“席狮舞”的动 作与过程所代表的意境与内在涵义,以使得“席狮舞”这一宝贵文化获得认知,让这一 非物质文化遗产得到有效的保护与传承 关键词:梅州客家,佛仪,席狮舞 1. Introduction Rituals originate from people’s spiritual beliefs, formed through the impact of their surroundings, mental demands, the development of culture as well as the structure of knowledge, and are developed and changed along with people’s social and working lives. -

Responses to Information Requests

RIR Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada www.irb-cisr.gc.ca Français Home Contact Us Help Search canada.gc.ca Home > Research > Responses to Information Requests RESPONSES TO INFORMATION REQUESTS (RIRs) New Search | About RIR's | Help 07 September 2005 CHN100387.E China: Situation of Protestants and treatment by authorities, particularly in Fujian and Guangdong (2001-2005) Research Directorate, Immigration and Refugee Board, Ottawa General Information Estimates of the number of Protestants in China vary among sources consulted by the Research Directorate. The Chinese government claims that there are more than 15 million adherents of the official Protestant Three-Self Patriotic Movement, although Protestant church officials put the number of worshippers who attend registered churches at 20 million (International Religious Freedom Report 2004 15 Sept. 2004). Estimates of the number of Protestants who belong to "unregistered" church groups range from 30 million to 50 million (Christian Science Monitor 8 Mar. 2004; U.S. News & World Report 30 Apr. 2001; see also International Religious Freedom Report 2004 15 Sept. 2004, Sec. 1). Some academics place the total number of Protestants in China at 90 million (ibid.). Sources agree that the number of Protestants is growing (ibid.; Christian Science Monitor 24 Dec. 2003; Economist 21 Apr. 2005), particularly among urban intellectuals, business people and university students (ibid.; Washington Post 24 Dec. 2002). Henan, the "Bethlehem" of China (Christian Science Monitor 8 Mar. 2004), reportedly has the largest number of Christians among all the provinces of China, with about five million worshippers, most of whom attend "house" churches (SCMP 9 Jan. 2002; see also U.S. -

L:\Ia-Dev\Frn\0502Frn\PRC Memo.Wpd

70 FR 5149, February 1, 2005 A-570-893 Investigation Proprietary Document Public Version IA/AD/CVD/9: JH, JDAL January 26, 2005 MEMORANDUM TO: James C. Doyle Office Director AD/CVD Enforcement, Office 9 THROUGH: Alex Villanueva Program Manager AD/CVD Enforcement, Office 9 FROM: Julia Hancock John D. La Rose Case Analysts RE: Antidumping Duty Investigation of Certain Frozen and Canned Warmwater Shrimp from the People’s Republic of China: Analysis of Ministerial Error Allegations1 I. SUMMARY The Department of Commerce (“the Department”) is amending the weighted-average dumping margins listed in the Final Determination for respondent Allied Pacific Group2 (“Allied Pacific”), four Section A Respondents, Zhoushan Xifeng Aquatic Co., Ltd. (“Zhoushan Xifeng”), Zhejiang Cereals, Oils & Foodstuff Import & Export Co., Ltd. (“Zhejiang Cereals”), Jinfu Trading Co., Ltd. (“Jinfu Trading”), Zhoushan Diciyuan Aquatic Products Co., Ltd. (“Zhoushan Diciyuan”), and the weighted-average Section A rate for all other respondents granted a separate rate. See Notice of Final Determination of 1 On January 21, 2005, the International Trade Commission (“ITC”) notified the Department of its final determination that two domestic like products exist for the merchandise covered by the Department's investigation: (i) certain non-canned warmwater shrimp and prawns, as defined above, and (ii) canned warmwater shrimp and prawns. The ITC determined that there is no injury regarding imports of canned warmwater shrimp and prawns from China, therefore, canned warmwater shrimp and prawns will not be covered by the antidumping order. 2 Allied Pacific Food (Dalian) Co., Ltd., Allied Pacific (H.K.) Co., Ltd., King Royal Investments, Ltd., Allied Pacific Aquatic Products (Zhanjiang) Co., Ltd., and Allied Pacific Aquatic Products (Zhongshan) Co., Ltd. -

Strongly Heterogeneous Transmission of COVID–19 in Mainland China: Local and Regional Variation

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.10.20033852; this version posted March 16, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under a CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license . Strongly heterogeneous transmission of COVID–19 in mainland China: local and regional variation Yuke Wang, MSc1, Peter Teunis, PhD1 March 10, 2020 Summary Background The outbreak of novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) started in the city of Wuhan, China, with a period of rapid initial spread. Transmission on a regional and then national scale was promoted by intense travel during the holiday period of the Chinese New Year. We studied the variation in transmission of COVID-19, locally in Wuhan, as well as on a larger spatial scale, among different cities and even among provinces in mainland China. Methods In addition to reported numbers of new cases, we have been able to assemble detailed contact data for some of the initial clusters of COVID-19. This enabled estimation of the serial interval for clinical cases, as well as reproduction numbers for small and large regions. Findings We estimated the average serial interval was 4·8 days. For early transmission in Wuhan, any infectious case produced as many as four new cases, transmission outside Wuhan was less in- tense, with reproduction numbers below two. During the rapid growth phase of the outbreak the region of Wuhan city acted as a hot spot, generating new cases upon contact, while locally, in other provinces, transmission was low. -

Tier 1 Manufacturing Sites

TIER 1 MANUFACTURING SITES - Produced January 2021 SUPPLIER NAME MANUFACTURING SITE NAME ADDRESS PRODUCT TYPE No of EMPLOYEES Albania Calzaturificio Maritan Spa George & Alex 4 Street Of Shijak Durres Apparel 100 - 500 Calzificio Eire Srl Italstyle Shpk Kombinati Tekstileve 5000 Berat Apparel 100 - 500 Extreme Sa Extreme Korca Bul 6 Deshmoret L7Nr 1 Korce Apparel 100 - 500 Bangladesh Acs Textiles (Bangladesh) Ltd Acs Textiles & Towel (Bangladesh) Tetlabo Ward 3 Parabo Narayangonj Rupgonj 1460 Home 1000 - PLUS Akh Eco Apparels Ltd Akh Eco Apparels Ltd 495 Balitha Shah Belishwer Dhamrai Dhaka 1800 Apparel 1000 - PLUS Albion Apparel Group Ltd Thianis Apparels Ltd Unit Fs Fb3 Road No2 Cepz Chittagong Apparel 1000 - PLUS Asmara International Ltd Artistic Design Ltd 232 233 Narasinghpur Savar Dhaka Ashulia Apparel 1000 - PLUS Asmara International Ltd Hameem - Creative Wash (Laundry) Nishat Nagar Tongi Gazipur Apparel 1000 - PLUS Aykroyd & Sons Ltd Taqwa Fabrics Ltd Kewa Boherarchala Gila Beradeed Sreepur Gazipur Apparel 500 - 1000 Bespoke By Ges Unip Lda Panasia Clothing Ltd Aziz Chowdhury Complex 2 Vogra Joydebpur Gazipur Apparel 1000 - PLUS Bm Fashions (Uk) Ltd Amantex Limited Boiragirchala Sreepur Gazipur Apparel 1000 - PLUS Bm Fashions (Uk) Ltd Asrotex Ltd Betjuri Naun Bazar Sreepur Gazipur Apparel 500 - 1000 Bm Fashions (Uk) Ltd Metro Knitting & Dyeing Mills Ltd (Factory-02) Charabag Ashulia Savar Dhaka Apparel 1000 - PLUS Bm Fashions (Uk) Ltd Tanzila Textile Ltd Baroipara Ashulia Savar Dhaka Apparel 1000 - PLUS Bm Fashions (Uk) Ltd Taqwa -

Shenzhen Sunspring Electronics Co., Ltd

SHENZHEN LCS COMPLIANCE TESTING LABORATORY LTD. Report No.: LCS171103073AE FCC 47 CFR PART 15 SUBPART B TEST REPORT KST DIGITAL TECHNOLOGY LIMITED Brushless Servo Model No.: X20-3612 Additional Model No.: X20-1035, X20-2208, X20-3012, X20-9650, BLS159, BLS651, BLS259, BLS359, BLS661, BLS662, BLS359WP, BLS805X, BLS815, BLS825, BLS905X, BLS915 Prepared for : KST DIGITAL TECHNOLOGY LIMITED Address : No.226, Pangu Street, Meixian, Meizhou, Guangdong Prepared by : Shenzhen LCS Compliance Testing Laboratory Ltd. Address : 1/F., Xingyuan Industrial Park, Tongda Road, Bao’an Avenue, Bao’an District, Shenzhen, Guangdong, China Tel : (+86)755-82591330 Fax : (+86)755-82591332 Web : www.LCS-cert.com Mail : [email protected] Date of receipt of test sample : November 07, 2017 Number of tested samples : 1 Serial number : Prototype Date of Test : November 07, 2017 ~ November 13, 2017 Date of Report : November 16, 2017 This report shall not be reproduced except in full, without the written approval of Shenzhen LCS Compliance Testing Laboratory Ltd. Page 1 of 14 SHENZHEN LCS COMPLIANCE TESTING LABORATORY LTD. Report No.: LCS171103073AE FCC -- TEST REPORT November 16, 2017 Test Report No. : LCS171103073AE Date of issue Type / Model........................... : X20-3612 EUT......................................... : Brushless Servo Applicant............................... : KST DIGITAL TECHNOLOGY LIMITED Address.................................. : No.226, Pangu Street, Meixian, Meizhou, Guangdong Telephone............................... : / Fax......................................... -

Factory Address Country

Factory Address Country Durable Plastic Ltd. Mulgaon, Kaligonj, Gazipur, Dhaka Bangladesh Lhotse (BD) Ltd. Plot No. 60&61, Sector -3, Karnaphuli Export Processing Zone, North Potenga, Chittagong Bangladesh Bengal Plastics Ltd. Yearpur, Zirabo Bazar, Savar, Dhaka Bangladesh ASF Sporting Goods Co., Ltd. Km 38.5, National Road No. 3, Thlork Village, Chonrok Commune, Korng Pisey District, Konrrg Pisey, Kampong Speu Cambodia Ningbo Zhongyuan Alljoy Fishing Tackle Co., Ltd. No. 416 Binhai Road, Hangzhou Bay New Zone, Ningbo, Zhejiang China Ningbo Energy Power Tools Co., Ltd. No. 50 Dongbei Road, Dongqiao Industrial Zone, Haishu District, Ningbo, Zhejiang China Junhe Pumps Holding Co., Ltd. Wanzhong Villiage, Jishigang Town, Haishu District, Ningbo, Zhejiang China Skybest Electric Appliance (Suzhou) Co., Ltd. No. 18 Hua Hong Street, Suzhou Industrial Park, Suzhou, Jiangsu China Zhejiang Safun Industrial Co., Ltd. No. 7 Mingyuannan Road, Economic Development Zone, Yongkang, Zhejiang China Zhejiang Dingxin Arts&Crafts Co., Ltd. No. 21 Linxian Road, Baishuiyang Town, Linhai, Zhejiang China Zhejiang Natural Outdoor Goods Inc. Xiacao Village, Pingqiao Town, Tiantai County, Taizhou, Zhejiang China Guangdong Xinbao Electrical Appliances Holdings Co., Ltd. South Zhenghe Road, Leliu Town, Shunde District, Foshan, Guangdong China Yangzhou Juli Sports Articles Co., Ltd. Fudong Village, Xiaoji Town, Jiangdu District, Yangzhou, Jiangsu China Eyarn Lighting Ltd. Yaying Gang, Shixi Village, Shishan Town, Nanhai District, Foshan, Guangdong China Lipan Gift & Lighting Co., Ltd. No. 2 Guliao Road 3, Science Industrial Zone, Tangxia Town, Dongguan, Guangdong China Zhan Jiang Kang Nian Rubber Product Co., Ltd. No. 85 Middle Shen Chuan Road, Zhanjiang, Guangdong China Ansen Electronics Co. Ning Tau Administrative District, Qiao Tau Zhen, Dongguan, Guangdong China Changshu Tongrun Auto Accessory Co., Ltd. -

Federal Register/Vol. 72, No. 176/Wednesday, September 12

Federal Register / Vol. 72, No. 176 / Wednesday, September 12, 2007 / Notices 52049 DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Quick-Frozen Industry Co., Ltd. definitions in the Harmonized Tariff (‘‘Meizhou’’); (6) Zhoushan Huading Schedule of the United States (‘‘HTS’’), International Trade Adminstration Seafood Co., Ltd. (‘‘Huading’’); (7) Asian are products which are processed from Seafoods (Zhanjiang) Co. (‘‘Asian warmwater shrimp and prawns through [A–570–893] Seafoods’’); and (8) Zhanjiang Evergreen freezing and which are sold in any Certain Frozen Warmwater Shrimp Aquatic Product Science and count size. From the People’s Republic of China: Technology Co., Ltd. (‘‘Evergreen’’). The The products described above may be Notice of Final Results and Rescission, new shipper review covers one processed from any species of in Part, of 2004/2006 Antidumping Duty producer/exporter: Hai Li Aquatic Co., warmwater shrimp and prawns. Administrative and New Shipper Ltd. Zhao An, Fujian (‘‘Hai Li’’). See Warmwater shrimp and prawns are Reviews Preliminary Results. The period of generally classified in, but are not review (‘‘POR’’) for both the limited to, the Penaeidae family. Some AGENCY: Import Administration, administrative and new shipper reviews examples of the farmed and wild-caught International Trade Administration, is July 16, 2004, through January 31, warmwater species include, but are not Department of Commerce. 2006. limited to, white-leg shrimp (Penaeus SUMMARY: On March 9, 2007, the On March 22, 2007, we issued a vannemei), banana prawn (Penaeus Department of Commerce (‘‘the supplemental questionnaire to Yelin, merguiensis), fleshy prawn (Penaeus Department’’) published the preliminary and received Yelin’s response on April chinensis), giant river prawn results of its administrative and new 5, 2007. -

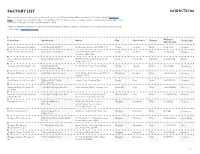

Factory List

FACTORY LIST Our commitment to transparency is core to our Corporate Social Responsibility efforts. Nordstrom’s Tier 1 factory list for Nordstrom Made, our family of private-label brands, is included below. This list reflects our most strategic suppliers, which we classify internally as Level 1 and Level 2. The data is current as of December 11, 2020. Additional information about our commitment to human rights, including our goals for ethical labor practices and women’s empowerment, can be found on nordstromcares.com. Factory Name Manufacturer Address City State/Province Country Employees Product Type (Male/Female) Industria de Calcados Karlitos Ltda. South Service Trading S/A Rua Benedito Merlino, 999, 14405-448 Franca Sao Paulo Brazil 146 (62/84) Footwear Industria de Calcados Kissol Ltda. South Service Trading S/A Rua Irmãos Antunes, 813, Jardim Franca Sao Paulo Brazil 196 (137/59) Footwear Guanabara, 14405-445 Eminent Garment (Cambodia) Eminent Garment Limited Phum Preak Thmey, Khum Teukvil, Srok Saang Khet Kandal Cambodia 866 (105/761) Woven Limited Saang, Phnom Penh Zhejiang Sunmans Knitting Co. Ltd. Royal Bermuda LLC No. 139 North of Biyun Road, 314400 Haining Zhejiang China 197 (39/158) Accessories West Coast Hosiery Group Dongguan Mayflower Footwear Corp. Pagoda International Footwear Golden Dragon Road, 1st Industrial Park of Dongcheng Dongguan China 500 (350/150) Footwear Sangyuan, 523119 Fujian Fuqing Huatai Footwear Co. Madden Intl. Ltd. Trading Lingjiao Village, Shangjing Town Fuqing Fujian China 360 (170/190) Footwear Ltd. Dolce Vita Intl. Nanyuan Knitting & Garments Co. South Asia Knitting Factory Ltd. Nanhua Industry District, Shengxin Town Nanan City Fujian China 604 (152/452) Sweaters Ltd.