March 13, 2021 Technical Editor-In-Chief Erica Hudson Founder/Advisor Michael P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

36 Csos and Individuals Urge the Council to Adopt a Resolution on Sudan

Letter from 36 NGOs and individuals regarding the human rights situation in Sudan in advance of the 33rd session of the UN Human Rights Council To Permanent Representatives of Members and Observer States of the UN Human Rights Council Geneva, Switzerland 7 September 2016 Re: Current human rights and humanitarian situation in Sudan Excellency, Our organisations write to you in advance of the opening of the 33rd session of the United Nations Human Rights Council to share our serious concerns regarding the human rights and humanitarian situation in Sudan. Many of these abuses are detailed in the attached annex. We draw your attention to the Sudanese government’s continuing abuses against civilians in South Kordofan, Blue Nile and Darfur, including unlawful attacks on villages and indiscriminate bombing of civilians. We are also concerned about the continuing repression of civil and political rights, in particular the ongoing crackdown on protesters and abuse of independent civil society and human rights defenders. In a recent example in March 2016, four representatives of Sudanese civil society were intercepted by security officials at Khartoum International Airport on their way to a high level human rights meeting with diplomats that took place in Geneva on 31 March. The meeting was organised by the international NGO, UPR Info, in preparation for the Universal Periodic Review (UPR) of Sudan that took place in May.1 We call upon your delegation to support the development and adoption of a strong and action- oriented resolution on Sudan under agenda item 4 at the 33rd session of the UN Human Rights Council. -

Simić Miroslav Tadić Simo Zarić

UNITED NATIONS International Tribunal for the Case No. IT-95-9-T Prosecution of Persons Responsible for Serious Violations of Date: 17 October 2003 International Humanitarian Law Committed in the Territory of Former Yugoslavia since 1991 Original: English IN TRIAL CHAMBER II Before: Judge Florence Ndepele Mwachande Mumba, Presiding Judge Sharon A. Williams Judge Per-Johan Lindholm Registrar: Mr. Hans Holthuis Judgement: 17 October 2003 PROSECUTOR v. BLAGOJE SIMIĆ MIROSLAV TADIĆ SIMO ZARIĆ JUDGEMENT The Office of the Prosecutor: Mr. Gramsci Di Fazio Mr. Philip Weiner Mr. David Re Counsel for the Accused: Mr. Igor Panteli} and Mr. Srdjan Vuković for Blagoje Simi} Mr. Novak Lukić and Mr. Dragan Krgović for Miroslav Tadić Mr. Borislav Pisarević and Mr. Aleksandar Lazarevi} for Simo Zarić PURL: https://www.legal-tools.org/doc/aa9b81/ I. INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................................1 II. GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS REGARDING THE EVALUATION OF EVIDENCE ...........7 III. DEMOGRAPHICS EXPERTS REPORTS .................................................................................11 IV. RELEVANT LAW ON ARTICLE 5 OF THE STATUTE.........................................................13 A. LAW ON GENERAL REQUIREMENTS OF ARTICLE 5 ......................................................................13 B. LAW ON PERSECUTION................................................................................................................16 1. General requirements: chapeau -

The Economics of Ethnic Cleansing in Darfur

The Economics of Ethnic Cleansing in Darfur John Prendergast, Omer Ismail, and Akshaya Kumar August 2013 WWW.ENOUGHPROJECT.ORG WWW.SATSENTINEL.ORG The Economics of Ethnic Cleansing in Darfur John Prendergast, Omer Ismail, and Akshaya Kumar August 2013 COVER PHOTO Displaced Beni Hussein cattle shepherds take shelter on the outskirts of El Sereif village, North Darfur. Fighting over gold mines in North Darfur’s Jebel Amer area between the Janjaweed Abbala forces and Beni Hussein tribe started early this January and resulted in mass displacement of thousands. AP PHOTO/UNAMID, ALBERT GONZALEZ FARRAN Overview Darfur is burning again, with devastating results for its people. A kaleidoscope of Janjaweed forces are once again torching villages, terrorizing civilians, and systematically clearing prime land and resource-rich areas of their inhabitants. The latest ethnic-cleans- ing campaign has already displaced more than 300,000 Darfuris this year and forced more than 75,000 to seek refuge in neighboring Chad, the largest population displace- ment in recent years.1 An economic agenda is emerging as a major driver for the escalating violence. At the height of the mass atrocities committed from 2003 to 2005, the Sudanese regime’s strategy appeared to be driven primarily by the counterinsurgency objectives and secondarily by the acquisition of salaries and war booty. Undeniably, even at that time, the government could have only secured the loyalty of its proxy Janjaweed militias by allowing them to keep the fertile lands from which they evicted the original inhabitants. Today’s violence is even more visibly fueled by monetary motivations, which include land grabbing; consolidating control of recently discovered gold mines; manipulating reconciliation conferences for increased “blood money”; expanding protection rackets and smuggling networks; demanding ransoms; undertaking bank robberies; and resum- ing the large-scale looting that marked earlier periods of the conflict. -

Sudan: Freedom

SUDAN: FREEDOM, PEACE, AND JUSTICE “we have risen, against those who stole our sweat.” Prepared by: Laura Stevens | Daphne Wang | Hashim Ismail Cover Photo Credit: https://www.voanews.com/africa/sudan-activists-call-justice-killed-protesters Table of Contents 1 Executive Summary 1 Methods 1 Background 2 End User 2 Stakeholders 4 Fragility Risk Assessment 9 ALC Analysis 10 Scenarios 11 Policy Options 15 Bibliography 20 Annexes 20 Annex 1: Fragility in Sudan According to Different Indices 20 Annex 2: Definitions and Additional Readings 22 Annex 3: Timeline of Major Events in the Last Five Years (Trends and Trajectory) 23 Annex 4: History of Recent Conflicts 24 Annex 5: Further Detail on Stakeholders 27 Annex 6: Social contract 28 Annex 7: Agriculture as part of the economy 28 Annex 8: State Sponsor of Terrorism 29 Annex 9: Security and Displacement Figures 32 Annex 10: Household Economic Data 33 Annex 11: Donor Profile 34 Annex 12: ALC Assessment Graphic 34 Annex 13: Additional Policy Information 36 Endnotes Acronyms ACC Anti-Corruption Committee ALC Authority, Legitimacy, Capacity AU African Union CIFP Country Indicators for Foreign Policy CPA Comprehensive Peace Agreement CSO Civil Society Organization EU European Union FAO Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations FDI Foreign Direct Investment FFC Forces for Freedom and Change FY Fiscal Year GDP Gross Domestic Product GEF Global Environment Facility HD Human Development ICC International Criminal Court IDPs Internally Displaced Persons IMF International Monetary Fund INGO -

Memorial of the Republic of Croatia

INTERNATIONAL COURT OF JUSTICE CASE CONCERNING THE APPLICATION OF THE CONVENTION ON THE PREVENTION AND PUNISHMENT OF THE CRIME OF GENOCIDE (CROATIA v. YUGOSLAVIA) MEMORIAL OF THE REPUBLIC OF CROATIA APPENDICES VOLUME 5 1 MARCH 2001 II III Contents Page Appendix 1 Chronology of Events, 1980-2000 1 Appendix 2 Video Tape Transcript 37 Appendix 3 Hate Speech: The Stimulation of Serbian Discontent and Eventual Incitement to Commit Genocide 45 Appendix 4 Testimonies of the Actors (Books and Memoirs) 73 4.1 Veljko Kadijević: “As I see the disintegration – An Army without a State” 4.2 Stipe Mesić: “How Yugoslavia was Brought Down” 4.3 Borisav Jović: “Last Days of the SFRY (Excerpts from a Diary)” Appendix 5a Serb Paramilitary Groups Active in Croatia (1991-95) 119 5b The “21st Volunteer Commando Task Force” of the “RSK Army” 129 Appendix 6 Prison Camps 141 Appendix 7 Damage to Cultural Monuments on Croatian Territory 163 Appendix 8 Personal Continuity, 1991-2001 363 IV APPENDIX 1 CHRONOLOGY OF EVENTS1 ABBREVIATIONS USED IN THE CHRONOLOGY BH Bosnia and Herzegovina CSCE Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe CK SKJ Centralni komitet Saveza komunista Jugoslavije (Central Committee of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia) EC European Community EU European Union FRY Federal Republic of Yugoslavia HDZ Hrvatska demokratska zajednica (Croatian Democratic Union) HV Hrvatska vojska (Croatian Army) IMF International Monetary Fund JNA Jugoslavenska narodna armija (Yugoslav People’s Army) NAM Non-Aligned Movement NATO North Atlantic Treaty Organisation -

Uganda's Fading Luster: Environmental Security in the Pearl of Africa

Uganda’sUganda’s FadingFading Luster:Luster: EnvironmentalEnvironmental SecuritySecurity inin thethe PearlPearl ofof AfricaAfrica A Pilot Case Study Foundation for Environmental Security and Sustainability June 2006 “Yet it is not possible to descend the Nile continuously from its source at Ripon Falls without realizing that the best lies behind one. Uganda is the pearl.” - Winston Churchill, My African Journey, 1908. The Foundation for Environmental Security and Sustainability (FESS) is a public policy foundation established to advance knowledge and provide practical solutions for key environmental security concerns around the world. FESS combines empirical analysis with in-country research to construct policy-relevant analyses and recommendations to address environmental conditions that pose risks to national, regional, and global security and stability. Co-Executive Director: Ray Simmons Co-Executive Director: Darci Glass-Royal The Partnership for African Environmental Sustainability (PAES) is a non- governmental organization established to promote environmentally and socially sustainable development in Africa. PAES focuses on policy studies and assists countries to strengthen their capacities in four program areas: environmental security; sustainable development strategies; sustainable land management; and natural resource assessment. PAES is headquartered in Kampala, Uganda, with offices in Washington, D.C. and Lusaka, Zambia. President and CEO: Mersie Ejigu This report was produced in 2006 by the Foundation for Environmental Security and Sustainability. The principal writers were Mersie Ejigu, Christine Mataya, Jeffrey Stark, and Ellen Suthers. Additional contributions were made by field research team members Eric Dannenmaier, Joëlle DuMont, Sauda Katenda, Loren Remsburg, and Sileshi Tsegaye. Cover photo: Kabale District Christine Mataya Acknowledgement FESS would like to thank staff at USAID/EGAT/ESP in Washington, DC as well the USAID Mission in Kampala for their encouragement and support. -

Gnetum Value Chain1

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Win-wins in forest product value chains? How governance impacts the sustainability of livelihoods based on non-timber forest products from Cameroon Ingram, V.J. Publication date 2014 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Ingram, V. J. (2014). Win-wins in forest product value chains? How governance impacts the sustainability of livelihoods based on non-timber forest products from Cameroon. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:30 Sep 2021 7 Gnetum value chain1 This chapter presents the results of the in-depth analysis of the Gnetum spp. value chain originating from the Southwest and Littoral regions of Cameroon and extending to consumers in Nigeria and Europe. -

The Chinese Stance on the Darfur Conflict

OCCASIONAL PAPER NO 67 China in Africa Project September 2010 The Chinese Stance on the Darfur Conflict Gaafar Karrar Ahmed s ir a f f A l a n o ti a rn e nt f I o te tu sti n In rica . th Af hts Sou sig al in Glob African perspectives. About SAIIA The South African Institute of International Affairs (SAIIA) has a long and proud record as South Africa’s premier research institute on international issues. It is an independent, non-government think-tank whose key strategic objectives are to make effective input into public policy, and to encourage wider and more informed debate on international affairs with particular emphasis on African issues and concerns. It is both a centre for research excellence and a home for stimulating public engagement. SAIIA’s occasional papers present topical, incisive analyses, offering a variety of perspectives on key policy issues in Africa and beyond. Core public policy research themes covered by SAIIA include good governance and democracy; economic policymaking; international security and peace; and new global challenges such as food security, global governance reform and the environment. Please consult our website www.saiia.org.za for further information about SAIIA’s work. About the C h INA IN AFRICA PR o J e C t SAIIA’s ‘China in Africa’ research project investigates the emerging relationship between China and Africa; analyses China’s trade and foreign policy towards the continent; and studies the implications of this strategic co-operation in the political, military, economic and diplomatic fields. The project seeks to develop an understanding of the motives, rationale and institutional structures guiding China’s Africa policy, and to study China’s growing power and influence so that they will help rather than hinder development in Africa. -

PUBLLISHED by Radovan Karadzic: Wartime Leader’S Years on Trial

PUBLLISHED BY Radovan Karadzic: Wartime Leader’s Years on Trial A collection of all the articles published by BIRN about Radovan Karadzic’s trial before the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia and the UN’s International Residual Mechanism for Criminal Tribunals. This e-book contains news stories, analysis pieces, interviews and other articles on the trial of the former Bosnian Serb leader for crimes including genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity during the conflict in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Produced by the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network. Introduction Radovan Karadzic was the president of Bosnia’s Serb-dominated Repub- lika Srpska during wartime, when some of the most horrific crimes were committed on European soil since World War II. On March 20, 2019, the 73-year-old Karadzic faces his final verdict after being initially convicted in the court’s first-instance judgment in March 2016, and then appealing. The first-instance verdict found him guilty of the Srebrenica genocide, the persecution and extermination of Croats and Bosniaks from 20 municipal- ities across Bosnia and Herzegovina, and being a part of a joint criminal enterprise to terrorise the civilian population of Sarajevo during the siege of the city. He was also found guilty of taking UN peacekeepers hostage. Karadzic was initially indicted by the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia in 1995. He then spent 12 years on the run, and was finally arrested in Belgrade in 2008 and extradited to the UN tribunal. As the former president of the Republika Srpska and the supreme com- mander of the Bosnian Serb Army, he was one of the highest political fig- ures indicted by the Hague court. -

Sudan: Non Arab Darfuris

Country Policy and Information Note Sudan: Non Arab Darfuris Version 1.0 August 2017 Preface This note provides country of origin information (COI) and policy guidance to Home Office decision makers on handling particular types of protection and human rights claims. This includes whether claims are likely to justify the granting of asylum, humanitarian protection or discretionary leave and whether – in the event of a claim being refused – it is likely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under s94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002. Decision makers must consider claims on an individual basis, taking into account the case specific facts and all relevant evidence, including: the policy guidance contained with this note; the available COI; any applicable caselaw; and the Home Office casework guidance in relation to relevant policies. Country information COI in this note has been researched in accordance with principles set out in the Common EU [European Union] Guidelines for Processing Country of Origin Information (COI) and the European Asylum Support Office’s research guidelines, Country of Origin Information report methodology, namely taking into account its relevance, reliability, accuracy, objectivity, currency, transparency and traceability. All information is carefully selected from generally reliable, publicly accessible sources or is information that can be made publicly available. Full publication details of supporting documentation are provided in footnotes. Multiple sourcing is normally used to ensure that the information is accurate, balanced and corroborated, and that a comprehensive and up-to-date picture at the time of publication is provided. Information is compared and contrasted, whenever possible, to provide a range of views and opinions. -

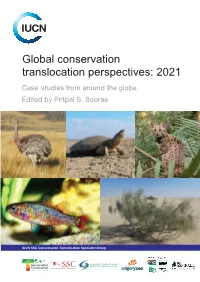

Global Conservation Translocation Perspectives: 2021. Case Studies from Around the Globe

Global conservation Global conservation translocation perspectives: 2021 translocation perspectives: 2021 IUCN SSC Conservation Translocation Specialist Group Global conservation translocation perspectives: 2021 Case studies from around the globe Edited by Pritpal S. Soorae IUCN SSC Conservation Translocation Specialist Group (CTSG) i The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN or any of the funding organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of IUCN. IUCN is pleased to acknowledge the support of its Framework Partners who provide core funding: Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark; Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland; Government of France and the French Development Agency (AFD); the Ministry of Environment, Republic of Korea; the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (Norad); the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida); the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) and the United States Department of State. Published by: IUCN SSC Conservation Translocation Specialist Group, Environment Agency - Abu Dhabi & Calgary Zoo, Canada. Copyright: © 2021 IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non- commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. Citation: Soorae, P. S. -

Language and the Orang-Utan: the Old 'Person' of the Forest*

Language and the Orang-utan: The Old 'Person' of the Forest* H. LYN WHITE MILES I still maintain, that his [the orang-utan] being possessed of the capacity of acquiring it [language], by having both the human intelligence and the organs of pronunciation, joined to the dispositions and affections of his mind, mild, gentle, and humane, is sufficient to denominate him a man. Lord J. B. Monboddo, Of the Origin and Progress of Language, 17731 If we base personhood on linguistic and mental ability, we should now ask, 'Are orang-utans or other creatures persons?' The issues this question raises are complex, but certainly arrogance and ignorance have played a role in our reluctance to recognise the intellectual capacity of our closest biological relatives - the nonhuman great apes. We have set ourselves apart from other animals, because of the scope of our mental abilities and cultural achievements. Although there were religious perspectives that did not emphasise our estrangement from nature, such as the doctrine of St. Francis and forms of nature religions, the dominant Judeo-Christian tradition held that white 'man' was separate and was given dominion over the earth, including other races, women, children and animals. Western philosophy continued this imperious attitude with the views of Descartes, who proposed that animals were just like machines with no significant language, feelings or thoughts. Personhood was denied even to some human groups enslaved by Euro-American colonial institutions. Only a century or so ago, scholarly opinion held that the speech of savages was inferior to the languages of complex societies. While nineteenth-century anthropologists arrogantly concerned themselves with measurements of human skulls to determine racial superiority, there was not much sympathy for the notion that animals might also be persons.