Uganda's Fading Luster: Environmental Security in the Pearl of Africa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ethiopia's Kechene Jewish Community

Supporting Isolated and Emerging Jewish Communities Around the Globe “All of Us” Volume 17, Number 1 SPRING, 2010 Ethiopia’s Kechene Jewish Community A History Lesson and Challenge by Judy Manelis I had always wanted to visit Ethiopia and meet mem- bers of the Jewish community there. The closest I came, however, was in the 80’s when I met Ethiopians in Israel during the airlift and greeted them at an ab- sorption center in Ashkelon right after they landed on Israeli soil. One of the perks, you might say, of being at the time executive director of Hadassah. However, Kechene potter a visit to Ethiopia itself never materialized. That fact Photo by Laura Alter Klapman changed in January of this year when several Kulanu board members, myself included, traveled to Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, to visit the newly emerging Jewish When I first heard of the Kechene Jewish community, community living in the Kechene neighborhood of the which calls itself Beit Avraham, I was intrigued. First city. there was Amy Cohen’s excellent article “The Long Road Home” in the Spring, 2009, issue of the Kulanu newsletter. Then, there was “The Kechene Jews of Ethiopia,” prepared last summer by members of the IN THIS ISSUE community who are now living in the United States. (See www.kulanu.org/ethiopia for both articles.) I ETHIOPIA ’S K E CH E N E .....................................1 have excerpted some paragraphs from the latter as a ABAYUDAYA DE V E LOPM E NT ............................2 way to introduce them: SURINAM E ’S RABBI ......................................10 ZIMBABW E ’S L E MBA .....................................12 The Kechene Jews share ancestral origins with the Beta Is- rael and, like those Ethiopian Jews, most of whom are now SOUTH AFRICA ’S LE MBA ...............................14 in Israel, they observe pre-Talmudic Jewish practices. -

Vote:511 Jinja District Quarter1

Local Government Quarterly Performance Report FY 2018/19 Vote:511 Jinja District Quarter1 Terms and Conditions I hereby submit Quarter 1 performance progress report. This is in accordance with Paragraph 8 of the letter appointing me as an Accounting Officer for Vote:511 Jinja District for FY 2018/19. I confirm that the information provided in this report represents the actual performance achieved by the Local Government for the period under review. Name and Signature: Accounting Officer, Jinja District Date: 30/10/2018 cc. The LCV Chairperson (District) / The Mayor (Municipality) 1 Local Government Quarterly Performance Report FY 2018/19 Vote:511 Jinja District Quarter1 Summary: Overview of Revenues and Expenditures Overall Revenue Performance Ushs Thousands Approved Budget Cumulative Receipts % of Budget Received Locally Raised Revenues 5,039,582 2,983,815 59% Discretionary Government Transfers 4,063,070 1,063,611 26% Conditional Government Transfers 35,757,925 9,198,562 26% Other Government Transfers 2,554,377 432,806 17% Donor Funding 564,000 0 0% Total Revenues shares 47,978,954 13,678,794 29% Overall Expenditure Performance by Workplan Ushs Thousands Approved Cumulative Cumulative % Budget % Budget % Releases Budget Releases Expenditure Released Spent Spent Planning 183,102 22,472 21,722 12% 12% 97% Internal Audit 132,830 32,942 27,502 25% 21% 83% Administration 6,994,221 1,589,106 1,385,807 23% 20% 87% Finance 1,399,200 320,632 310,572 23% 22% 97% Statutory Bodies 995,388 234,790 160,795 24% 16% 68% Production and Marketing 1,435,191 -

Presents Children of Uganda Tuesday, April 25Th 10Am

Presents Children of Uganda Tuesday, April 25th 10am and noon, Concert Hall Study Guides are also available on our website at www.fineartscenter.com - select Performances Plus! from Educational Programs, then select Resource room. The Fine Arts Center wishes to acknowledge MassMutual Financial Group for its important role in making these educational materials and programs available to the youth in our region. About this Guide The Children of Uganda 2006 Education Guide is intended to enhance the experience of students and teachers attending performances and activities integral to Children of Uganda’s 2006 national tour. This guide is not comprehensive. Please use the information here in conjunction with other materials that meet curricular standards of your local community in such subjects as history, geography, current af- fairs, arts & culture, etc. Unless otherwise credited, all photos reproduced in this guide © Vicky Leland. The Children of Uganda 2006 tour is supported, in part, with a generous grant from the Monua Janah Memorial Foundation, in memory of Ms. Monua Janah who was deeply touched by the Children of Uganda, and sought to help them, and children everywhere, in her life. © 2006 Uganda Children’s Charity Foundation. All rights reserved. Permissions to copy this Education Guide are granted only to presenters of Children of Uganda’s 2006 national tour. For other permissions and uses of this guide (in whole or in part), contact Uganda Children’s Charity Foundation PO Box 140963 Dallas TX 75214 Tel (214) 824-0661 [email protected] www.childrenofuganda.org 2| Children of Uganda Education Guide 2006 The Performance at a glance With pulsing rhythms, quicksilver movements, powerful drums, and bold songs of cele- bration and remembrance, Children of Uganda performs programs of East African music and dance with commanding skill and an awesome richness of human spirit. -

GET-Fit Annual Report 2016.Pdf

GET FiT UGANDA | ANNUAL REPORT 2016 ANNUAL REPORT 2016 This report including all content and illustration has been prepared by and In cooperation with PAGE 3 MESSAGE FROM ERA The Electricity Regulatory Authority continues to recognize the great role played by the GET FiT program in supporting Uganda towards achieving the policy objective regarding the prioritization of renewable energy in the national generation mix. Eng. Ziria Tibalwa Waako, AG. Chief Executive Officer GET FiT UGANDA | ANNUAL REPORT 2016 he year 2016 saw the impact of the GET modelling, and standards for interconnection and FiT program on Uganda’s Electricity wheeling arrangement. The facility has enabled Supply Industry grow from strength the Authority to build capacity to ensure long to strength. In addition to the six (6) term sustainability beyond the GET FiT Program. Thydropower projects that broke ground in 2015, construction works began for six (6) more power It is notable that the implementation of the GET plants in 2016 and early 2017, bringing the total FiT program saw Uganda become one of the best of the planned installed capacity from the GET Renewable energy investment destinations and FiT projects currently under construction to 86 gain international recognition. The Bloomberg MW. ratings of 2016 rated the country 2nd best with regard to Renewable Energy investments in Furthermore, on December 12, 2016, the Ugandan Africa. In an effort to maintain the favourable Electricity Supply Industry through GET FiT Renewable Energy Investment climate, the support achieved yet another major milestone Authority with support from the GET FIT program of commissioning the first grid connected Solar revised the Renewable Energy Feed in Tariffs in Photovoltaic Plant in the country. -

Bigwala Mus Ic and Dance of the Bas Oga People

BIGWALA MUSIC AND DANCE OF THE BASOGA PEOPLE written by James Isabirye 2012 Background The Basoga are Bantu speaking people who live in southeastern Uganda. They are neighbors to the Baganda, Bagwere, Basamia, Banyoli and Banyoro people. The Basoga are primarily subsistence agricultural people. "Bigwala” is a Lusoga language term that refers to a set of five or more monotone gourd trumpets of different sizes. The music of the trumpets and the dance performed to that music are both called “Bigwala”. Five drums accompany “Bigwala” music and they include a big drum “Engoma e ne ne ”, a long drum “Omugaabe,” short drum “Endyanga”, a medium size drum “Mbidimbidi” and a small drum “Enduumi ” each of which plays a specific role in the set. Bigwala heritage is of significant palace / royal importance because of its ritualistic role during burial of kings, coronations and their anniversaries and stands as one of the main symbols of Busoga kingship. When King Henry Wako M uloki passed away on 1st September 2008, the "Bigwala" players were invited to Nakabango palace and Kaliro burial ground to perform their funeral function. 1 During the coronation of late king Henry Wako Muloki on 11th February 1995; the Bigwala players performed their ritual roles. It is important to note that Busoga kingdom like all others had been abolished in 1966 by the Ugandan republic government of Obote I and all aspects its existence were jeopardised including the Bigwala. The Kingship is the only main uniting identity which represents the Basoga, offers them opportunity to exist in a value system, focuses their initiatives to deal with development issues with in the framework of their ethnic society and connects them to their cherished past. -

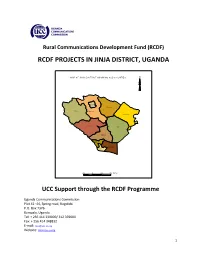

Rcdf Projects in Jinja District, Uganda

Rural Communications Development Fund (RCDF) RCDF PROJECTS IN JINJA DISTRICT, UGANDA MAP O F JINJA DIS TR ICT S HO W ING S UB CO U NTIES N B uw enge T C B uy engo B uta gaya B uw enge Bus ed de B udon do K ak ira Mafubira Mpum udd e/ K im ak a Masese/ Ce ntral wa lukub a Div ision 20 0 20 40 Kms UCC Support through the RCDF Programme Uganda Communications Commission Plot 42 -44, Spring road, Bugolobi P.O. Box 7376 Kampala, Uganda Tel: + 256 414 339000/ 312 339000 Fax: + 256 414 348832 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ucc.co.ug 1 Table of Contents 1- Foreword……………………………………………………………….……….………..…..…....………3 2- Background…………………………………….………………………..…………..….….……..………4 3- Introduction………………….……………………………………..…….…………….….……….…...4 4- Project profiles……………………………………………………………………….…..…….……....5 5- Stakeholders’ responsibilities………………………………………………….….…........…12 6- Contacts………………..…………………………………………….…………………..…….……….13 List of tables and maps 1- Table showing number of RCDF projects in Jinja district………………l….…….….5 2- Map of Uganda showing Jinja district………..………………….………………....…….14 10- Map of Jinja district showing sub counties………..…………………………………..15 11- Table showing the population of Jinja district by sub counties……………….15 12- List of RCDF Projects in Jinja District…………………………………….………..…..…16 Abbreviations/Acronyms UCC Uganda Communications Commission RCDF Rural Communications Development Fund USF Universal Service Fund MCT Multipurpose Community Tele-centre PPDA Public Procurement and Disposal Act of 2003 POP Internet Points of Presence ICT Information and Communications Technology UA Universal Access MoES Ministry of Education and Sports MoH Ministry of Health DHO District Health Officer CAO Chief Administrative Officer RDC Resident District Commissioner 2 1. Foreword ICTs are a key factor for socio-economic development. -

Energy Efficiency Roadmap for Uganda Making Energy Efficiency Count

Energy Efficiency Roadmap for Uganda Making Energy Efficiency Count ENERGY EFFICIENCY ROADMAP FOR UGANDA Making Energy Efficiency Count Authors: Stephane de la Rue du Can,1 David Pudleiner,2 David Jones,3 and Aleisha Khan4 This work was supported by Power Africa under Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231. Published May 2017 1 Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory 2 ICF International 3 Tetra Tech 4 ICF International i ENERGY EFFICIENCY ROADMAP FOR UGANDA DISCLAIMERS This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor The Regents of the University of California, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference therein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof, or The Regents of the University of California. The views of the authors do not necessarily reflect those of the United States Government or any agency thereof, or The Regents of the University of California. Ernest Orlando Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory is an equal opportunity -

THE UGANDA GAZETTE [13Th J Anuary

The THE RH Ptrat.ir OK I'<1 AND A T IE RKPt'BI.IC OF UGANDA Registered at the Published General Post Office for transmission within by East Africa as a Newspaper Uganda Gazette A uthority Vol. CX No. 2 13th January, 2017 Price: Shs. 5,000 CONTEXTS P a g e General Notice No. 12 of 2017. The Marriage Act—Notice ... ... ... 9 THE ADVOCATES ACT, CAP. 267. The Advocates Act—Notices ... ... ... 9 The Companies Act—Notices................. ... 9-10 NOTICE OF APPLICATION FOR A CERTIFICATE The Electricity Act— Notices ... ... ... 10-11 OF ELIGIBILITY. The Trademarks Act—Registration of Applications 11-18 Advertisements ... ... ... ... 18-27 I t is h e r e b y n o t if ie d that an application has been presented to the Law Council by Okiring Mark who is SUPPLEMENTS Statutory Instruments stated to be a holder of a Bachelor of Laws Degree from Uganda Christian University, Mukono, having been No. 1—The Trade (Licensing) (Grading of Business Areas) Instrument, 2017. awarded on the 4th day of July, 2014 and a Diploma in No. 2—The Trade (Licensing) (Amendment of Schedule) Legal Practice awarded by the Law Development Centre Instrument, 2017. on the 29th day of April, 2016, for the issuance of a B ill Certificate of Eligibility for entry of his name on the Roll of Advocates for Uganda. No. 1—The Anti - Terrorism (Amendment) Bill, 2017. Kampala, MARGARET APINY, 11th January, 2017. Secretary, Law Council. General N otice No. 10 of 2017. THE MARRIAGE ACT [Cap. 251 Revised Edition, 2000] General Notice No. -

Deadly Profits: Illegal Wildlife Trafficking Through Uganda And

Cover: The carcass of an elephant killed by militarized poachers. Garamba National Park, DRC, April 2016. Photo: African Parks Deadly Profits Illegal Wildlife Trafficking through Uganda and South Sudan By Ledio Cakaj and Sasha Lezhnev July 2017 Executive Summary Countries that act as transit hubs for international wildlife trafficking are a critical, highly profitable part of the illegal wildlife smuggling supply chain, but are frequently overlooked. While considerable attention is paid to stopping illegal poaching at the chain’s origins in national parks and changing end-user demand (e.g., in China), countries that act as midpoints in the supply chain are critical to stopping global wildlife trafficking. They are needed way stations for traffickers who generate considerable profits, thereby driving the market for poaching. This is starting to change, as U.S., European, and some African policymakers increasingly recognize the problem, but more is needed to combat these key trafficking hubs. In East and Central Africa, South Sudan and Uganda act as critical waypoints for elephant tusks, pangolin scales, hippo teeth, and other wildlife, as field research done for this report reveals. Kenya and Tanzania are also key hubs but have received more attention. The wildlife going through Uganda and South Sudan is largely illegally poached at alarming rates from Garamba National Park in the Democratic Republic of Congo, South Sudan, points in West Africa, and to a lesser extent Uganda, as it makes its way mainly to East Asia. Worryingly, the elephant -

Gnetum Value Chain1

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Win-wins in forest product value chains? How governance impacts the sustainability of livelihoods based on non-timber forest products from Cameroon Ingram, V.J. Publication date 2014 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Ingram, V. J. (2014). Win-wins in forest product value chains? How governance impacts the sustainability of livelihoods based on non-timber forest products from Cameroon. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:30 Sep 2021 7 Gnetum value chain1 This chapter presents the results of the in-depth analysis of the Gnetum spp. value chain originating from the Southwest and Littoral regions of Cameroon and extending to consumers in Nigeria and Europe. -

Corporate Social Responsibility

CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY BY KAKIRA SUGAR LIMITED AND BUSOGA SUGARCANE GROWERS ASSOCIATION VOLUME 8 - April 2018 Foreword from the Chairperson BOARD It is a great honor and privilege to bring this message to our readers the opportunity to access this profile with regard to our great successes. Kakira Outgrowers Rural Development Fund (KORD) was incorporated as a company limited by guarantee and is registered under the NGO Statute. The core partners are Kakira Sugar Ltd (KSL) and Busoga Sugarcane Growers Association (BSGA). The objective of the company among others is to create an enabling environment for sugarcane farmers to access cheap loans from Banks and to develop the catchment Dr. E.T.S Adriko area by rendering social – economic and infrastructural services. report which led to the establishment of and Development (2016). Received a KORD. KORD is the first vehicle of its kind Certificate of Appreciation from St. Johns • Performed the role of the implementing to involve a unique funding mechanism by Church Bulanga for KORDs efforts in agency for various projects funded the core partners (KSL and BSGA) that is fighting child labor and enrolling children by partners and other agencies. also conducive to leveraging donor funds. back to school in Bulanga Parish – Luuka These projects include; Orphans and District. vulnerable children Project (USAID/ It is important to note that the KORD Uganda Private Health Support Program model of corporate social responsibility I would like to appreciate donor agencies and USAID/Health Initiative for the (giving back to the community) is an (CARDNO Emerging Markets USA Ltd/ Private Sector), Diary Improvement innovative model that has brought the two USAID, Foundation for Sustainable Project (Uganda National Council partners (BSGA and KSL) to a good working Development, Uganda National Council of Science and Technology, Dairy relationship. -

Mapping a Better Future

Wetlands Management Department, Ministry of Water and Environment, Uganda Uganda Bureau of Statistics International Livestock Research Institute World Resources Institute The Republic of Uganda Wetlands Management Department MINISTRY OF WATER AND ENVIRONMENT, UGANDA Uganda Bureau of Statistics Mapping a Better Future How Spatial Analysis Can Benefi t Wetlands and Reduce Poverty in Uganda ISBN: 978-1-56973-716-3 WETLANDS MANAGEMENT DEPARTMENT UGANDA BUREAU OF STATISTICS MINISTRY OF WATER AND ENVIRONMENT Plot 9 Colville Street P.O. Box 9629 P.O. Box 7186 Kampala, Uganda Kampala, Uganda www.wetlands.go.ug www.ubos.org The Wetlands Management Department (WMD) in the Ministry of Water and The Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS), established in 1998 as a semi-autonomous Environment promotes the conservation of Uganda’s wetlands to sustain their governmental agency, is the central statistical offi ce of Uganda. Its mission is to ecological and socio-economic functions for the present and future well-being of continuously build and develop a coherent, reliable, effi cient, and demand-driven the people. National Statistical System to support management and development initiatives. Sound wetland management is a responsibility of everybody in Uganda. UBOS is mandated to carry out the following activities: AUTHORS AND CONTRIBUTORS WMD informs Ugandans about this responsibility, provides technical advice and X Provide high quality central statistics information services. training about wetland issues, and increases wetland knowledge through research, X Promote standardization in the collection, analysis, and publication of statistics This publication was prepared by a core team from four institutions: mapping, and surveys. This includes the following activities: to ensure uniformity in quality, adequacy of coverage, and reliability of Wetlands Management Department, Ministry of Water and Environment, Uganda X Assessing the status of wetlands.