Mapping a Better Future

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DISTRICT BASELINE: Nakasongola, Nakaseke and Nebbi in Uganda

EASE – CA PROJECT PARTNERS EAST AFRICAN CIVIL SOCIETY FOR SUSTAINABLE ENERGY & CLIMATE ACTION (EASE – CA) PROJECT DISTRICT BASELINE: Nakasongola, Nakaseke and Nebbi in Uganda SEPTEMBER 2019 Prepared by: Joint Energy and Environment Projects (JEEP) P. O. Box 4264 Kampala, (Uganda). Supported by Tel: +256 414 578316 / 0772468662 Email: [email protected] JEEP EASE CA PROJECT 1 Website: www.jeepfolkecenter.org East African Civil Society for Sustainable Energy and Climate Action (EASE-CA) Project ALEF Table of Contents ACRONYMS ......................................................................................................................................... 4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT .................................................................................................................... 5 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................. 6 CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................. 8 1.1 Background of JEEP ............................................................................................................ 8 1.2 Energy situation in Uganda .................................................................................................. 8 1.3 Objectives of the baseline study ......................................................................................... 11 1.4 Report Structure ................................................................................................................ -

Kayunga District Statistical Abstract for 2017/2018

Kayunga District Statistical Abstract for 2017/2018 THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA KAYUNGA DISTRICT LOCAL GOVERNMENT STATISTICAL ABSTRACT 2017/18 Kayunga District Local Government P.O Box 18000, Kayunga Tel: +256-xxxxxx September 2018 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.Kayunga.go.ug i Kayunga District Statistical Abstract for 2017/2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS .................................................................................................................... II LIST OF TABLES .............................................................................................................................. V FOREWORD .................................................................................................................................. VIII ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ................................................................................................................... IX LIST OF ACRONYMS ....................................................................................................................... X GLOSSARY ..................................................................................................................................... XI EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................ XIII GENERAL INFORMATION ABOUT THE DISTRICT ..................................................................... XVI CHAPTER 1: BACKGROUND INFORMATION ................................................................................ -

Profit Making for Smallholder Farmers Proceedings of the 5Th MATF Experience Sharing Workshop 25Th - 29Th May 2009, Entebbe, Uganda

Profit Making for Smallholder Farmers Proceedings of the 5th MATF Experience Sharing Workshop 25th - 29th May 2009, Entebbe, Uganda Profit Making for Small Holder Farmers 1 Charles Katusabe with his cow he G.ilbert/MATF : purchased from his garlic income Photo 2 MATF 5th Grant Holders’ Workshop Profit Making for Smallholder Farmers Proceedings of the 5th MATF Experience Sharing Workshop 25th - 29th May 2009, Entebbe, Uganda Editors: Dr. Ralph Roothaert and Gilbert Muhanji Workshop organisers: Chris Webo, Fatuma Buke, Gilbert Muhanji, Monicah Nyang, Dr. Ralph Roothaert and Renison Kilonzo. Preferred citation: R. Roothaert and G. Muhanji (Eds), 2009. Profit Making for Smallholder Farmers. Proceedings of the 5th MATF Experience Sharing Workshop, 25th - 29th May 2009, Entebbe, Uganda. FARM-Africa, Nairobi, 44 pp. This book is an output of the Maendeleo Agricultural Technology Fund (MATF), with joint funding from the Rockefeller Foundation and the Gatsby Charitable Foundation since 2002, and funded by the Kilimo Trust since 2005. The views expressed are not necessarily those of the Kilimo Trust as the contents are solely the responsibility of the authors. MATF is managed by the Food and Agricultural Research Management (FARM)-Africa. © Food and Agricultural Research Management (FARM)-Africa, 2009 Profit Making for Small Holder Farmers 1 Contents Executive summary 3 Acknowledgement 5 Abbreviations and acronyms 6 1.0 INTRODUCTION 7 1.1 FARM-Africa and MATF 7 1.2 Round V 8 1.3 The workshop 9 1.4 Highlights from minister’s speech 10 2.0 PROJECT -

Ending CHILD MARRIAGE and TEENAGE PREGNANCY in Uganda

ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA A FORMATIVE RESEARCH TO GUIDE THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE NATIONAL STRATEGY ON ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA Final Report - December 2015 ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA 1 A FORMATIVE RESEARCH TO GUIDE THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE NATIONAL STRATEGY ON ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA A FORMATIVE RESEARCH TO GUIDE THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE NATIONAL STRATEGY ON ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA Final Report - December 2015 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The United Nations Children Fund (UNICEF) gratefully acknowledges the valuable contribution of many individuals whose time, expertise and ideas made this research a success. Gratitude is extended to the Research Team Lead by Dr. Florence Kyoheirwe Muhanguzi with support from Prof. Grace Bantebya Kyomuhendo and all the Research Assistants for the 10 districts for their valuable support to the research process. Lastly, UNICEF would like to acknowledge the invaluable input of all the study respondents; women, men, girls and boys and the Key Informants at national and sub national level who provided insightful information without whom the study would not have been accomplished. I ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA A FORMATIVE RESEARCH TO GUIDE THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE NATIONAL STRATEGY ON ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ..................................................................................I -

Mapping a Healthier Future

Health Planning Department, Ministry of Health, Uganda Directorate of Water Development, Ministry of Water and Environment, Uganda Uganda Bureau of Statistics International Livestock Research Institute World Resources Institute The Republic of Uganda Health Planning Department MINISTRY OF HEALTH, UGANDA Directorate of Water Development MINISTRY OF WATER AND ENVIRONMENT, UGANDA Uganda Bureau of Statistics Mapping a Healthier Future ISBN: 978-1-56973-728-6 How Spatial Analysis Can Guide Pro-Poor Water and Sanitation Planning in Uganda HEALTH PLANNING DEPARTMENT MINISTRY OF HEALTH, UGANDA Plot 6 Lourdel Road P.O. Box 7272 AUTHORS AND CONTRIBUTORS Kampala, Uganda http://www.health.go.ug/ This publication was prepared by a core team from fi ve institutions: The Health Planning Department at the Ministry of Health (MoH) leads eff orts to provide strategic support Health Planning Department, Ministry of Health, Uganda to the Health Sector in achieving sector goals and objectives. Specifi cally, the Planning Department guides Paul Luyima sector planning; appraises and monitors programmes and projects; formulates, appraises and monitors Edward Mukooyo national policies and plans; and appraises regional and international policies and plans to advise the sector Didacus Namanya Bambaiha accordingly. Francis Runumi Mwesigye Directorate of Water Development, Ministry of Water and Environment, Uganda DIRECTORATE OF WATER DEVELOPMENT Richard Cong MINISTRY OF WATER AND ENVIRONMENT, UGANDA Plot 21/28 Port Bell Road, Luzira Clara Rudholm P.O. Box 20026 Disan Ssozi Kampala, Uganda Wycliff e Tumwebaze http://www.mwe.go.ug/MoWE/13/Overview Uganda Bureau of Statistics The Directorate of Water Development (DWD) is the lead government agency for the water and sanitation Thomas Emwanu sector under the Ministry of Water and Environment (MWE) with the mandate to promote and ensure the rational and sustainable utilization, development and safeguard of water resources for social and economic Bernard Justus Muhwezi development, as well as for regional and international peace. -

"A Revision of the Freshwater Crabs of Lake Kivu, East Africa."

Northern Michigan University NMU Commons Journal Articles FacWorks 2011 "A revision of the freshwater crabs of Lake Kivu, East Africa." Neil Cumberlidge Northern Michigan University Kirstin S. Meyer Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.nmu.edu/facwork_journalarticles Part of the Biology Commons Recommended Citation Cumberlidge, Neil and Meyer, Kirstin S., " "A revision of the freshwater crabs of Lake Kivu, East Africa." " (2011). Journal Articles. 30. https://commons.nmu.edu/facwork_journalarticles/30 This Journal Article is brought to you for free and open access by the FacWorks at NMU Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of NMU Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. This article was downloaded by: [Cumberlidge, Neil] On: 16 June 2011 Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 938476138] Publisher Taylor & Francis Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37- 41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Journal of Natural History Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713192031 The freshwater crabs of Lake Kivu (Crustacea: Decapoda: Brachyura: Potamonautidae) Neil Cumberlidgea; Kirstin S. Meyera a Department of Biology, Northern Michigan University, Marquette, Michigan, USA Online publication date: 08 June 2011 To cite this Article Cumberlidge, Neil and Meyer, Kirstin S.(2011) 'The freshwater crabs of Lake Kivu (Crustacea: Decapoda: Brachyura: Potamonautidae)', Journal of Natural History, 45: 29, 1835 — 1857 To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/00222933.2011.562618 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00222933.2011.562618 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. -

Buikwe District Economic Profile

BUIKWE DISTRICT LOCAL GOVERNMENT P.O.BOX 3, LUGAZI District LED Profile A. Map of Buikwe District Showing LLGs N 1 B. Background 1.1 Location and Size Buikwe District lies in the Central region of Uganda, sharing borders with the District of Jinja in the East, Kayunga along river Sezibwa in the North, Mukono in the West, and Buvuma in Lake Victoria. The District Headquarters is in BUIKWE Town, situated along Kampala - Jinja road (11kms off Lugazi). Buikwe Town serves as an Administrative and commercial centre. Other urban centers include Lugazi, Njeru and Nkokonjeru Town Councils. Buikwe District has a total area of about 1209 Square Kilometres of which land area is 1209 square km. 1.2 Historical Background Buikwe District is one of the 28 districts of Uganda that were created under the local Government Act 1 of 1997. By the act of parliament, the district was inniatially one of the Counties of Mukono district but later declared an independent district in July 2009. The current Buikwe district consists of One County which is divided into three constituencies namely Buikwe North, Buikwe South and Buikwe West. It conatins 8 sub counties and 4 Town councils. 1.3 Geographical Features Topography The northern part of the district is flat but the southern region consists of sloping land with great many undulations; 75% of the land is less than 60o in slope. Most of Buikwe District lies on a high plateau (1000-1300) above sea level with some areas along Sezibwa River below 760m above sea level, Southern Buikwe is a raised plateau (1220-2440m) drained by River Sezibwa and River Musamya. -

Priority Service Provision Under Decentralization: a Case Study of Maternal and Child Health Care in Uganda

Small Applied Research No. 10 Priority Service Provision under Decentralization: A Case Study of Maternal and Child Health Care in Uganda December 1999 Prepared by: Frederick Mwesigye, M.A Makerere University Abt Associates Inc. n 4800 Montgomery Lane, Suite 600 Bethesda, Maryland 20814 n Tel: 301/913-0500 n Fax: 301/652-3916 In collaboration with: Development Associates, Inc. n Harvard School of Public Health n Howard University International Affairs Center n University Research Co., LLC Funded by: U.S. Agency for International Development Mission The Partnerships for Health Reform (PHR) Project seeks to improve people’s health in low- and middle-income countries by supporting health sector reforms that ensure equitable access to efficient, sustainable, quality health care services. In partnership with local stakeholders, PHR promotes an integrated approach to health reform and builds capacity in the following key areas: > Better informed and more participatory policy processes in health sector reform; > More equitable and sustainable health financing systems; > Improved incentives within health systems to encourage agents to use and deliver efficient and quality health services; and > Enhanced organization and management of health care systems and institutions to support specific health sector reforms. PHR advances knowledge and methodologies to develop, implement, and monitor health reforms and their impact, and promotes the exchange of information on critical health reform issues. December 1999 Recommended Citation Mwesigye, Frederick. 1999. Priority Service Provision Under Decentralization: A Case Study of Maternal and Child Health Care in Uganda. Small Applied Research Paper No. 10. Bethesda, MD: Partnerships for Health Reform Project, Abt Associates Inc. For additional copies of this report, contact the PHR Resource Center at [email protected] or visit our website at www.phrproject.com. -

Usaid's Malaria Action Program for Districts

USAID’S MALARIA ACTION PROGRAM FOR DISTRICTS GENDER ANALYSIS MAY 2017 Contract No.: AID-617-C-160001 June 2017 USAID’s Malaria Action Program for Districts Gender Analysis i USAID’S MALARIA ACTION PROGRAM FOR DISTRICTS Gender Analysis May 2017 Contract No.: AID-617-C-160001 Submitted to: United States Agency for International Development June 2017 USAID’s Malaria Action Program for Districts Gender Analysis ii DISCLAIMER The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) or the United States Government. June 2017 USAID’s Malaria Action Program for Districts Gender Analysis iii Table of Contents ACRONYMS ...................................................................................................................................... VI EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................... VIII 1. INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................................................................1 2. BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................................1 COUNTRY CONTEXT ...................................................................................................................3 USAID’S MALARIA ACTION PROGRAM FOR DISTRICTS .................................................................6 STUDY DESCRIPTION..................................................................................................................6 -

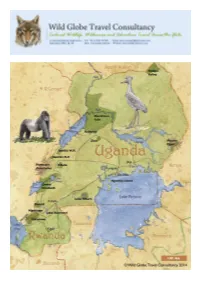

Uganda and Rwanda

Uganda: The Long Way Round - 50 Days Major Destinations Entebbe - Lake Victoria - Ngamba Island - Jinja - Mabira Forest Reserve - Sipi Falls - Mount Elgon National Park - Kidepo Valley National Park - Murchison Falls National Park - Budongo Forest Reserve - Ziwa Rhino Sanctuary - Semliki Wildlife Reserve - Semliki National Park - Kibale National Park - Bigodi Wetlands Sanctuary - Rwenzori Mountains National Park - Queen Elizabeth National Park - Bwindi Impenetrable National Park - Mgahinga Gorilla National Park - Volcanoes National Park - Kigali - Lake Bunyonyi - Lake Mburo National Park - Entebbe Tour Highlights and Activities Uganda’s geography is very different than its East Africa neighbours Kenya and Tanzania, as it has far more of the lush forested areas that flourish across the ‘equatorial forest belt’ of central and western Africa. Consequently it does not have the vast rolling savannahs of Kenya and particularly Tanzania, or the huge proliferation of plains animals that these countries are famous for. It is also only now recovering from the widespread poaching that went unchecked during years of violent conflict and political turmoil, which resulted in the destruction of massive animal populations and the local extinction of the rhino and wild dog. Although poaching does still occur in Uganda, as it sadly does all over Africa, the wildlife is now receiving a serious level of protection and is recovering remarkably well in most areas. The 2012 Uganda Wildlife Authority figures fully support this recovery, as the populations of many large species have more than doubled since the previous census in 1999, with the number of impala rising from around 1,600 to over 35,000. Elephant, buffalo, giraffe, zebra, hippo and waterbuck populations have all increased significantly, confirming what those of us visiting regularly already knew, the animals are returning and Uganda is once again featuring as one of the top wildlife destinations on this or any other continent. -

SET III Living Together in East Africa

SET III Living Together in East Africa. Major Resources of East Africa. Meaning of resources/Examples. A resource is a feature in the environment that man uses to satisfy their /his needs. Types of natural resources. Renewable resources. Renewable resources are resources that can be replaced naturally once they are over- exploited. Non-renewable resources are resources that cannot be replace naturally once they are over-used or exhausted. Examples of renewable resources. • Plants • Animals • Water bodies • Land • Climate /rainfall/sunshine Examples of non-renewable resources • Minerals • Fossils fuel i.e. coal, oil, natural, gas Land • Land is the part of the earth that is not covered by water • Land supports most resources in the environment. 1 Importance of land • Land provides space for building houses / settlement. • Land is where crops are grown. • Land provides space for burying the dead. • Land provides space for grazing animals. • Minerals are mined from land. Problems facing land. • Dumping of garbage and toxic materials on land. • Over-cultivation • Deforestation • Land fragmentation • Soil erosion Possible solutions to some of the above problems. • Garbage should be used for other purposes like generation of biogas. • People should be encouraged to grow fodder crops for animals. • People should be encouraged to use manure and fertilizer. • Farmers should terrace their land to control soil erosion. • Educate the people about the benefits of re-afforestation. Note: There are things that people make to meet their needs and they are called human made resources. Examples include; - Electricity - Clothes - Shoes - Mobile phones - Books - Buildings - Vehicles - Drugs - Roads 2 Activity 1. What are natural resources? ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 2. -

The Charcoal Grey Market in Kenya, Uganda and South Sudan (2021)

COMMODITY REPORT BLACK GOLD The charcoal grey market in Kenya, Uganda and South Sudan SIMONE HAYSOM I MICHAEL McLAGGAN JULIUS KAKA I LUCY MODI I KEN OPALA MARCH 2021 BLACK GOLD The charcoal grey market in Kenya, Uganda and South Sudan ww Simone Haysom I Michael McLaggan Julius Kaka I Lucy Modi I Ken Opala March 2021 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors would like to thank everyone who gave their time to be interviewed for this study. They would like to extend particular thanks to Dr Catherine Nabukalu, at the University of Pennsylvania, and Bryan Adkins, at UNEP, for playing an invaluable role in correcting our misperceptions and deepening our analysis. We would also like to thank Nhial Tiitmamer, at the Sudd Institute, for providing us with additional interviews and information from South Sudan at short notice. Finally, we thank Alex Goodwin for excel- lent editing. Interviews were conducted in South Sudan, Uganda and Kenya between February 2020 and November 2020. ABOUT THE AUTHORS Simone Haysom is a senior analyst at the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime (GI-TOC), with expertise in urban development, corruption and organized crime, and over a decade of experience conducting qualitative fieldwork in challenging environments. She is currently an associate of the Oceanic Humanities for the Global South research project based at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg. Ken Opala is the GI-TOC analyst for Kenya. He previously worked at Nation Media Group as deputy investigative editor and as editor-in-chief at the Nairobi Law Monthly. He has won several journalistic awards in his career.