Priority Service Provision Under Decentralization: a Case Study of Maternal and Child Health Care in Uganda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ending CHILD MARRIAGE and TEENAGE PREGNANCY in Uganda

ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA A FORMATIVE RESEARCH TO GUIDE THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE NATIONAL STRATEGY ON ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA Final Report - December 2015 ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA 1 A FORMATIVE RESEARCH TO GUIDE THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE NATIONAL STRATEGY ON ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA A FORMATIVE RESEARCH TO GUIDE THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE NATIONAL STRATEGY ON ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA Final Report - December 2015 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The United Nations Children Fund (UNICEF) gratefully acknowledges the valuable contribution of many individuals whose time, expertise and ideas made this research a success. Gratitude is extended to the Research Team Lead by Dr. Florence Kyoheirwe Muhanguzi with support from Prof. Grace Bantebya Kyomuhendo and all the Research Assistants for the 10 districts for their valuable support to the research process. Lastly, UNICEF would like to acknowledge the invaluable input of all the study respondents; women, men, girls and boys and the Key Informants at national and sub national level who provided insightful information without whom the study would not have been accomplished. I ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA A FORMATIVE RESEARCH TO GUIDE THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE NATIONAL STRATEGY ON ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ..................................................................................I -

Buikwe District Economic Profile

BUIKWE DISTRICT LOCAL GOVERNMENT P.O.BOX 3, LUGAZI District LED Profile A. Map of Buikwe District Showing LLGs N 1 B. Background 1.1 Location and Size Buikwe District lies in the Central region of Uganda, sharing borders with the District of Jinja in the East, Kayunga along river Sezibwa in the North, Mukono in the West, and Buvuma in Lake Victoria. The District Headquarters is in BUIKWE Town, situated along Kampala - Jinja road (11kms off Lugazi). Buikwe Town serves as an Administrative and commercial centre. Other urban centers include Lugazi, Njeru and Nkokonjeru Town Councils. Buikwe District has a total area of about 1209 Square Kilometres of which land area is 1209 square km. 1.2 Historical Background Buikwe District is one of the 28 districts of Uganda that were created under the local Government Act 1 of 1997. By the act of parliament, the district was inniatially one of the Counties of Mukono district but later declared an independent district in July 2009. The current Buikwe district consists of One County which is divided into three constituencies namely Buikwe North, Buikwe South and Buikwe West. It conatins 8 sub counties and 4 Town councils. 1.3 Geographical Features Topography The northern part of the district is flat but the southern region consists of sloping land with great many undulations; 75% of the land is less than 60o in slope. Most of Buikwe District lies on a high plateau (1000-1300) above sea level with some areas along Sezibwa River below 760m above sea level, Southern Buikwe is a raised plateau (1220-2440m) drained by River Sezibwa and River Musamya. -

Rakai Health Sciences Program (Formerly Rakai Project)

Rakai Health Sciences Program (formerly Rakai Project) 1. Physical Geography Rakai District is one of the 56 administrative districts of Uganda and lies between longitudes 31oE and 32oE, and latitudes 0oS and 1oS. The district is located in the south-west of the country bordering the Republic of Tanzania in the south. The district has a total area of 4,973 Sq. Kms, with 3,889 sq. kms being land with a total population of 467,215. The Rakai Health Sciences program, was initiated as Rakai Project in 1988 to study the magnitude and dynamics of the HIV disease. It represents a collaboration between the Uganda Virus Research Inst. of Uganda’s Ministry of Health, researchers at Makerere University, Kampala, Columbia University, New York and Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. 2. Procedures The project conducts extensive community epidemiologic and behavioral studies to document the HIV/STD epidemics and risk factors, implements HIV/STD preventive services and undertakes large community randomized intervention trials for HIV prevention, STD control and prevention of adverse outcomes of pregnancy. The Rakai Community Cohort Study (RCCS) conducted by the Rakai Health Sciences Program in Rakai District, provides a unique resource for hypothesis generating and hypothesis testing research on HIV and other infections (including TB, malaria, STDs, HPV) and on maternal and child health (including prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission and screening for cervical neoplasia). Using the RCCS as the basis for all activities, the Rakai Program has conducted major randomized HIV prevention trials, innovative operations research on prevention strategies; and has made fundamental contributions to knowledge of HIV transmission dynamics, viral molecular epidemiology (in preparation for HIV and HPV vaccine trials), novel findings regarding interactions between HIV and other co-infections (e.g., HSV-2, HHV-8, HCV, malaria, STDs and BV), and on the impact of HIV on fertility, family stability, marital violence and many other behavioral and demographic factors. -

WHO UGANDA BULLETIN February 2016 Ehealth MONTHLY BULLETIN

WHO UGANDA BULLETIN February 2016 eHEALTH MONTHLY BULLETIN Welcome to this 1st issue of the eHealth Bulletin, a production 2015 of the WHO Country Office. Disease October November December This monthly bulletin is intended to bridge the gap between the Cholera existing weekly and quarterly bulletins; focus on a one or two disease/event that featured prominently in a given month; pro- Typhoid fever mote data utilization and information sharing. Malaria This issue focuses on cholera, typhoid and malaria during the Source: Health Facility Outpatient Monthly Reports, Month of December 2015. Completeness of monthly reporting DHIS2, MoH for December 2015 was above 90% across all the four regions. Typhoid fever Distribution of Typhoid Fever During the month of December 2015, typhoid cases were reported by nearly all districts. Central region reported the highest number, with Kampala, Wakiso, Mubende and Luweero contributing to the bulk of these numbers. In the north, high numbers were reported by Gulu, Arua and Koti- do. Cholera Outbreaks of cholera were also reported by several districts, across the country. 1 Visit our website www.whouganda.org and follow us on World Health Organization, Uganda @WHOUganda WHO UGANDA eHEALTH BULLETIN February 2016 Typhoid District Cholera Kisoro District 12 Fever Kitgum District 4 169 Abim District 43 Koboko District 26 Adjumani District 5 Kole District Agago District 26 85 Kotido District 347 Alebtong District 1 Kumi District 6 502 Amolatar District 58 Kween District 45 Amudat District 11 Kyankwanzi District -

Table of Contents List of Tables

TABLE OF CONTENTS 6 PROJECT IMPACTS ................................................................................................................ 138 Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 138 Summary of Impacts ................................................................................................................. 138 Impacts on Land ....................................................................................................................... 143 6.3.1 Land Requirements and Land Use Context ......................................................................... 143 Impacts on houses – Physical Displacement ........................................................................... 149 Impacts on other structures ...................................................................................................... 153 Impacts on Communal Buildings .............................................................................................. 159 Graves and Cultural Heritage Assets ....................................................................................... 160 Impacts on Crops and Economic Trees .................................................................................... 160 Impacts on Livelihood Activities – Economic Displacement ..................................................... 166 Impacts on Public Utilities/Infrastructure .................................................................................. -

Mapping a Better Future

Wetlands Management Department, Ministry of Water and Environment, Uganda Uganda Bureau of Statistics International Livestock Research Institute World Resources Institute The Republic of Uganda Wetlands Management Department MINISTRY OF WATER AND ENVIRONMENT, UGANDA Uganda Bureau of Statistics Mapping a Better Future How Spatial Analysis Can Benefi t Wetlands and Reduce Poverty in Uganda ISBN: 978-1-56973-716-3 WETLANDS MANAGEMENT DEPARTMENT UGANDA BUREAU OF STATISTICS MINISTRY OF WATER AND ENVIRONMENT Plot 9 Colville Street P.O. Box 9629 P.O. Box 7186 Kampala, Uganda Kampala, Uganda www.wetlands.go.ug www.ubos.org The Wetlands Management Department (WMD) in the Ministry of Water and The Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS), established in 1998 as a semi-autonomous Environment promotes the conservation of Uganda’s wetlands to sustain their governmental agency, is the central statistical offi ce of Uganda. Its mission is to ecological and socio-economic functions for the present and future well-being of continuously build and develop a coherent, reliable, effi cient, and demand-driven the people. National Statistical System to support management and development initiatives. Sound wetland management is a responsibility of everybody in Uganda. UBOS is mandated to carry out the following activities: AUTHORS AND CONTRIBUTORS WMD informs Ugandans about this responsibility, provides technical advice and X Provide high quality central statistics information services. training about wetland issues, and increases wetland knowledge through research, X Promote standardization in the collection, analysis, and publication of statistics This publication was prepared by a core team from four institutions: mapping, and surveys. This includes the following activities: to ensure uniformity in quality, adequacy of coverage, and reliability of Wetlands Management Department, Ministry of Water and Environment, Uganda X Assessing the status of wetlands. -

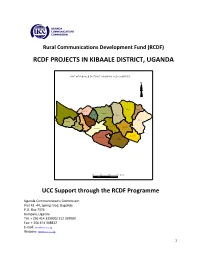

Rcdf Projects in Kibaale District, Uganda

Rural Communications Development Fund (RCDF) RCDF PROJECTS IN KIBAALE DISTRICT, UGANDA MAP O F KIBAAL E DISTRIC T SHO WIN G SUB CO UNTIES N N alwe yo Kisiita R uga sha ri M pee fu Kiry a ng a M aba al e Kakin do Nko ok o Bw ika ra Ky an aiso ke Kag ad i M uho ro Kyeb an do Kasa m by a M uga ra m a Kib aa le TC Bwan s wa Bw am iram ira M atale 10 0 10 20 Kms UCC Support through the RCDF Programme Uganda Communications Commission Plot 42 -44, Spring road, Bugolobi P.O. Box 7376 Kampala, Uganda Tel: + 256 414 339000/ 312 339000 Fax: + 256 414 348832 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ucc.co.ug 1 Table of Contents 1- Foreword……………………………………………………………….……….………..………....……3 2- Background…………………………………….………………………..…………..….….….…..……4 3- Introduction………………….……………………………………..…….…………….….….………..4 4- Project profiles……………………………………………………………………….…..…….……...5 5- Stakeholders’ responsibilities………………………………………………….….…........…12 6- Contacts………………..…………………………………………….…………………..…….……….13 List of tables and maps 1- Table showing number of RCDF projects in Kibaale district………….………..….5 2- Map of Uganda showing Kibaale district………..………………….………...……..….14 10- Map of Kibaale district showing sub counties………..…………………………..….15 11- Table showing the population of Kibaale district by sub counties…………..15 12- List of RCDF Projects in Kibaale district…………………………………….…….……..16 Abbreviations/Acronyms UCC Uganda Communications Commission RCDF Rural Communications Development Fund USF Universal Service Fund MCT Multipurpose Community Tele-centre PPDA Public Procurement and Disposal Act of 2003 POP Internet Points of Presence ICT Information and Communications Technology UA Universal Access MoES Ministry of Education and Sports MoH Ministry of Health DHO District Health Officer CAO Chief Administrative Officer RDC Resident District Commissioner 2 1. -

National Guidelines: Managing Healthcare Waste Generated from Safe Male Circumcision Procedures | I

AUGUST 2013 This publication was made possible through the support of the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) through the U.S. Agency for International Development under contract number GHH-I-00-07-00059-00, AIDS Support and Technical Assistance Resources (AIDSTAR-One) Project, Sector I, Task Order 1. Uganda National Guidelines: Managing Healthcare Waste Generated from Safe Male Circumcision Procedures | i Acronyms ACP AIDS Control Programme HCW health care waste HCWM health care waste management IP implementing partner MoH Ministry of Health NDA National Drug Authority NEMA National Environmental Management Authority PEPFAR U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief PHC primary health center PMTCT prevention of mother-to-child transmission POP persistent organic pollutants SMC safe male circumcision STI sexually transmitted infections UAC Uganda AIDS Commission UNBOS Uganda National Bureau of Standards USG U.S. Government WHO World Health Organization ii | Uganda National Guidelines: Managing Healthcare Waste Generated from Safe Male Circumcision Procedures Table of Contents Acronyms ......................................................................................................................................................... ii Preface ............................................................................................................................................................. v 1.0 BACKGROUND ......................................................................................................................................... -

The Face of Chronic Poverty in Uganda As Seen by the Poor Themselves

The Face of Chronic Poverty in Uganda as seen by the Poor Themselves Charles Lwanga-Ntalea and Kimberley McCleanb Chronic Poverty Research Centre – Uganda, and aDevelopment Research and Training, PO Box 1599, Kampala, Uganda and bMaK A Di Consulting, PO Box 636, Mona Vale, NSW 1660, Australia Abstract: This study examines the factors influencing chronic poverty in Uganda. The findings are based on participatory poverty assessments conducted in 23 peri-urban / urban and 57 rural sites in 21 districts. It examines definitions of chronic poverty, the types of people who are chronically poor and why; opportunities and constraints for moving out of poverty; the effects of government policies; and suggestions for improvements. Chronic poverty was described as a state of perpetual need” “due to a lack of the basic necessities” and the “means of production”; social support; and feelings of frustration and powerlessness. For many, it was inter-generationally transmitted and of long duration. Multiple compounding factors, such as attitude, access to productive resources, weather conditions, HIV/AIDS, physical infirmity and gender, worsened the severity of poverty. The major categories of the chronically poor included the disabled, widows, chronic poor married women, street kids and orphans, the elderly, the landless, casual labourers, refugees and the internally displaced and youth. Factors that maintain the poor in poverty included the lack of productive assets, exploitation and discrimination, lack of opportunities, low education and lack of skills, ignorance, weather, disability or illness, and disempowerment. For the chronically poor, GOU policies and practices - taxation, land tenure, market liberalisation, civil service reform and privatisation - were reported to maintain them in poverty. -

Mobility and Crisis in Gulu Drivers, Dynamics and Challenges of Rural to Urban Mobility

Mobility and crisis in Gulu Drivers, dynamics and challenges of rural to urban mobility SUBMITTED TO THE RESEARCH AND EVIDENCE FACILITY FEBRUARY 2018 Contents Map of Ethiopia, Kenya and Uganda 3 Summary 4 1. Introduction 6 Project context and aims of research 6 Significance of the site of investigation 6 Methodology 8 Constraints and limitations 8 2. Research setting and context 9 Socio-cultural context 9 Economic context 10 Rural to urban mobility in historical perspective 13 Impact on urban development 16 3. Migrant experiences 19 Drivers of migration 19 Role of social networks 24 Opportunities and challenges 26 Financial practices of migrants 30 Impact on sites of origin 32 Onward migration 34 4. Conclusion 35 Bibliography 37 This report was written by Ronald Kalyango with contributions from Isabella Amony and Kindi Fred Immanuel. This report was edited by Kate McGuinnes. Cover image: Gulu bus stop, Gulu, Uganda © Ronald Kalyango. This report was commissioned by the Research and Evidence Facility (REF), a research consortium led by the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London and funded by the EU Trust Fund. The Rift Valley Institute works in eastern and central Africa to bring local knowledge to bear on social, political and economic development. Copyright © Rift Valley Institute 2018. This work is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). Map of Ethiopia, Kenya and Uganda FROM CRISIS TO STABILITY? RURAL TO URBAN MOBILITY TO GULU 3 Summary Gulu Municipality is among the fastest growing urban centres in Uganda. In 1991, it was the fourth largest with a population of 38,297. -

UGANDA COUNTRY of ORIGIN INFORMATION (COI) REPORT COI Service

UGANDA COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION (COI) REPORT COI Service Date 20 April 2011 UGANDA DATE Contents Preface Latest News EVENTS IN UGANDA FROM 3 FEBRUARY TO 20 APRIL 2011 Useful news sources for further information REPORTS ON UGANDA PUBLISHED OR ACCESSED BETWEEN 3 FEBRUARY AND 20 APRIL 2011 Paragraphs Background Information 1. GEOGRAPHY ............................................................................................................ 1.01 Map ........................................................................................................................ 1.06 2. ECONOMY ................................................................................................................ 2.01 3. HISTORY .................................................................................................................. 3.01 Political developments: 1962 – early 2011 ......................................................... 3.01 Conflict with Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA): 1986 to 2010.............................. 3.07 Amnesty for rebels (Including LRA combatants) .............................................. 3.09 4. RECENT DEVELOPMENTS ........................................................................................... 4.01 Kampala bombings July 2010 ............................................................................. 4.01 5. CONSTITUTION.......................................................................................................... 5.01 6. POLITICAL SYSTEM .................................................................................................. -

Ake ·To ·A Is E I S Ssessme

Lake Victoria fisheries catch assessment survey (CAS) information, Uganda 2005-2007 Item Type monograph Publisher National Fisheries Resources Research Institute Download date 28/09/2021 15:21:06 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/35562 ake · to ·a is e i s ssessme 7 I - . ,_~ ~.. r ~~/.--.J .' . Introduction Management of fisheries resources requires information on the fish stocks; the magnitude, distribution and trends of fishing effort and the trends of fish catches. Catch Assessment SUNeys (CAS) in Lake Victoria are one of the ways through which the partner states sharing the lake are generating the key information required. The EU-funded Project, Implementation of a Fisheries Management Plan (IFMP) for Lake Victoria through the Lake Victoria Fisheries Organisation (LVFO) is supporting the implementation of regionally harmonized CAS in the lake, In the Uganda part of the lake, CAS activities are carried out at 54 fish landing sites in the 11 riparian districts. The National Fisheries Resources Research Institute (NaFIRRI), the Department of Fisheries Resources (DFR), and the Districts of Busla, Bugiri, Mayuge, Jinja, Mukono, Wakiso, Kampala, Mpigi, Masaka, Kalangala and Rakai jointly conduct the sUNeys, The CAS enumerators are recruited from the fishing communities and work under direct supeNision of sub-county fisheries officers. I CAS enumerators collecting data Wh"l Catch ASS€SSTn€T\t Surv€"IS? The CAS data are used to estimate Catch per Unit of Effort (CPUE) or Fish catch rates, which, are used together with Fishing Effort information obtained from Frame sUNeys to estimate: 1, The quantities of fish landed in the riparian districts along Lake Victoria; 2, The monetary value of the fish catches; and 3.