'-'L ---EVALUATING DRUG CONTROL EFFECTIVENESS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Date Rape and Steroid Panels, Updated Feb 1 2010

DRUG-FACILITATED SEXUAL ASSAULT (aka “DATE RAPE”) AND STEROID PANELS (Effective January 26, 2010) Basic Date Rape Panel Comprehensive Date Rape Panel • GHB (Hair Only) • Ketamine • GHB • Benzodiazepines, including Rohypnol • Benzodiazepines Alprazolam Clonazepam Alprazolam Clonazepam Diazepam Flunitrazepam (Rohypnol) Diazepam Flunitrazepam Lorazepam Oxazepam Lorazepam Oxazepam Temazepam Nitrazepam Temazepam Nitrazepam • Opioids Codeine Hydrocodone Comprehensive Date Rape Panel Meperidine Tramadol (Urine Only) Methadone Fentanyl • GHB • Sedatives/Hypnotics Ketamine Methaqualone • Barbiturates Zolpidem Zopiclone Amobarbital Butalbital Pentobarbital Phenobarbital • Over-The-Counter Drugs Secobarbital Diphenhydramine Dextromethorphan Doxylamine Chlorpheniramine • Benzodiazepines Brompheniramine Promethazine Alprazolam Clonazepam Pheniramine Diazepam Flunitrazepam Lorazepam Oxazepam • Muscle Relaxants Temazepam Nitrazepam Carisoprodol Meprobamate • Opioids Cyclobenzaprine Methocarbamol Codeine Morphine • Hallucinogens (PCP) Hydrocodone Hydromorphone Oxycodone Oxymorphone Meperidine Tramadol ANABOLIC STEROID PANEL Methadone Fentanyl (Urine or Blood) Propoxyphene Buprenorphine Androstenedione Boldenone • Sedatives/Hypnotics Fluoxymesterolone Mesterolone Ketamine Methaqualone 17-a-Methyltestosterone Methenolone Zolpidem Zopiclone Methandrostenolone Nandrolone • Over-The-Counter Drugs Norethandrolone Oxandrolone Diphenhydramine Dextromethorphan Stanozolol Trenbolone Doxylamine Chlorpheniramine Brompheniramine Promethazine Pheniramine For additional steroids, • Muscle Relaxants call for details and pricing Carisoprodol Meprobamate EXPERTOX, INC. Cyclobenzaprine Methocarbamol Blood should only be 1803 CENTER STREET, SUITE A submitted for date rape • Hallucinogens DEER PARK, TX 77536 PCP MDMA panels if within five (5) hours of 281.476.4600 MDA MDEA ingestion. FAX 281.930.8856 Cannabinoids (Carboxy-THC) • WWW.EXPERTOX.COM Turaround Time: Ten (10) Urine must be collected within five (5) days business days from specimen of drug exposure receipt at the lab . -

National Clearinghouse for Drug Abuse Information Selected Reference Series, Series 1, No

DOCUMENT RESOHE ED 090 455 CG 008 832 TITLE National Clearinghouse For Drug Abuse Information Selected Reference Series, Series 1, No. 1. INSTITUTION National Inst. of Mental Health (DHEW), Rockville, Hd. National Clearinghouse for Drug Abuse Information.; Student Association for the Study of Hallucinogens, Biloit, His. PDB DATE Nov 73 NOTE 13p. AVAILABLE FROM National Clearinghouse for Drug Abuse Information, p. 0. Box 1908, Rockville, Maryland 20850 EDRS PRICE MF-10.75 HC-S1.50 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS ^Bibliographies; *Drug Abuse; *Drug Education; *Drug Therapy; Government Publications; ^Narcotics ABSTRACT One of a series of bibliographies published by the National Clearinghouse for Drug Abuse Information, this reference focuses on the drug, methagualone. Literature is selected for inclusion on the basis of its currency, significance in the field, and its availability to the public. Materials are directed toward researchers, educators, lawyers, physicians, and members of the public with more than a general need for information. Citations are not annotated. (Author/CJ) SERIES 7, No.l NOVEMBER 1973 Each bibliography of the National Clearinghouse for Drug Abuse 3- Information Selected Reference Series is a representative listing of citations on subjects of topical interest. The selection of o literature is based on its currency, its significance in the field, and its availability in local bookstores or research libraries. The scope of the material is directed toward students writing research papers, special interest groups, such as educators, lawyers and phy sicians, and the general public requiring more resources than public information materials can provide. Each reference series is meant to present an overview of the existing literature, but is not meant to be comprehensive or definitive in scope. -

Chemistry Information Sheet Methaqualone © 2014 Beckman Coulter, Inc

SYNCHRON System(s) METQ Chemistry Information Sheet Methaqualone © 2014 Beckman Coulter, Inc. All rights reserved. 475021 For In Vitro Diagnostic Use Rx Only ANNUAL REVIEW Reviewed by Date Reviewed by Date PRINCIPLE INTENDED USE METQ reagent, in conjunction with UniCel® DxC 600/800 System(s) and SYNCHRON® Systems Drugs of Abuse Testing (DAT) Urine Calibrators, is intended for the qualitative determination of methaqualone in human urine at a cutoff value of 300 ng/mL. The METQ assay provides a rapid screening procedure for determining the presence of methaqualone (METQ) and its metabolites in urine. This test provides only a preliminary analytical result; a positive result by this assay should be conrmed by another generally accepted non-immunological method such as thin layer chromatography (TLC), gas chromatography (GC), or gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS). GC/MS is the preferred conrmatory method.1,2 Clinical consideration and professional judgement should be applied to any drug of abuse test result, particularly when preliminary positive results are used. CLINICAL SIGNIFICANCE Measurements of methaqualone are used as an aid in the diagnosis and treatment of methaqualone use or overdose. METHODOLOGY The Methaqualone assay utilizes a homogenous enzyme immunoassay method.3 The METQ reagent is comprised of specic antibodies which can detect methaqualone and its metabolites in urine. A drug-labeled glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PDH) conjugate competes with any free drug from the urine sample for a xed amount of antibody binding sites. In the absence of free drug from the sample, the drug-labeled G6PDH conjugate is bound by the specic antibody and the enzyme activity is inhibited. -

Injecting Drug Users Etc.)

Economic and Social Council E/NR/2015/3 Annual Reports Questionnaire Part Three. Extent and patterns of and trends in drug use Report of the Government of: Reporting Year: reporting. Completed on (date): (dd/mm/yyyy) Please upload completed questionnaire to: https://arq.unodc.org/ The completed annual report questionnaire is due on: official March 31, 2016 For technical support, contact: for Phone Fax Email UNODC Vienna (+43-1) 26060-3914 (+43-1) 26060-5866 [email protected] Not Note: This is a printable version of the annual report questionnaire, which is in the form of an Excel spreadsheet and is designed to be completed electronically. In this printable version, definitions of key terms used in the questionnairecopy. are provided in the footnotes, whenever relevant; in the electronic version, these definitions (and additional instructions) are repeated throughout the questionnaire through the “Comments” function in Excel. The Excel spreadsheet also uses drop-down lists for some questions, allowing respondents to simply select from a list the answer that is most appropriate for their country. Sample INSTRUCTIONS The annual report questionnaire consists of the following four parts: Part One. Legislative and institutional framework; Part Two. Comprehensive approach to drug demand reduction; Part Three. Extent, patterns and trends in drug use; Part Four. Extent and patterns of and trends in drug crop cultivation and drug manufacture and trafficking This is part three of the annual report questionnaire. Respondents are asked to complete all questions. Where no data are available, this should be indicated by inserting two dashes (--) or writing "not known" in the appropriate cell. -

METHAQUALONE Latest Revision: February 15, 1999

METHAQUALONE Latest Revision: February 15, 1999 1. SYNONYMS CFR: Methaqualone CAS #: Base: 72-44-6 Hydrochloride: 340-56-7 Other Names: 2-Methyl-3-(2-methylphenyl)-4-(3H)-quinazolinone 2-Methyl-3-o-tolyl-4-(3H)-quinazolinone Dormogen Metolquizolone Mandrax MAOA Motolon Quaalude Sopor 2. CHEMICAL AND PHYSICAL DATA 2.1. CHEMICAL DATA Form Chemical Formula Molecular Weight Melting Point (°C) Base C16H14N2O 250.3 114-116 Hydrochloride C16H15N2OCl 286.8 255-265 2.2. SOLUBILITY Form A C E H M W Base *** S P *** PS I Hydrochloride S S I *** S PS A = acetone, C = chloroform, E = ether, H = hexane, M = methanol and W = water, VS = very soluble, FS = freely soluble, S = soluble, PS = sparingly soluble, SS = slightly soluble, VSS = very slightly soluble and I = insoluble 3. SCREENING TECHNIQUES 3.1. COLOR TESTS REAGENT COLOR PRODUCED Acidified cobalt thiocyanate Blue Fischer-Morris Pink 3.2. CRYSTAL TESTS REAGENT CRYSTALS FORMED Potassium permanganate solution Plates Sodium carbonate solution Needles 3.3. THIN-LAYER CHROMATOGRAPHY Visualization Acidified iodoplatinate solution Brown-violet Dragendorff spray Yellow-orange RELATIVE R1 COMPOUND System System System TLC6 TLC5 TLC7 mecloqualone 0.8 1.0 1.0 methaqualone 1.0 1.0 1.0 o-toluidine 1.3 1.6 1.6 3.4. GAS CHROMATOGRAPHY Methaqualone is a thermally stable compound well suited for gas chromatography. It may however, have a similar retention time with cocaine in certain temperature programs. Method MEQ-GCS1 Instrument: Gas chromatograph operated in split mode with FID Column: 5% phenyl/95% methyl silicone 12 m x 0.2 mm x 0.33 µm film thickness Carrier gas: Helium at 1.0 mL/min Temperatures: Injector: 270°C Detector: 280°C Oven program: 1) 175°C initial temperature for 1.0 min 2) Ramp to 275°C at 15°C/min 3) Hold final temperature for 3.0 min Injection Parameters: Split Ratio = 60:1, 1 µL injected Samples are to be dissolved in chloroform and filtered. -

Receptive-Field Size of S1 Cortical Neurones Is Altered by Methaqualone Via a GABA Mechanism

THE CANADIAN JOURNAL OF NEUROLOGICAL SCIENCES Receptive-field Size of S1 Cortical Neurones is Altered by Methaqualone via a GABA Mechanism T.P. Hicks, T. Kaneko and J.-I. Oka ABSTRACT: Methaqualone (Mtq; quaaludes or 'ludes) is a controlled substance, having a molecular structure related to the imidiazobenzodiazepine series of drugs, that has gained some notoriety recently due to its history of widespread abuse on the street. Users report experiencing peripheral paresthesia and transient numbness on body parts receiving dense cutaneous innervation (lips, fingertips, etc.). Since the receptive-field (RF)-sizes of many primary somatosensory (SI) cortical neurones are controlled by local, gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)-mediated inhibitory processes, we tested Mtq to see whether its clinical symptoms might have a basis in an action through central GABA-mediated synaptic processes. This report supports this contention and describes a likely pharmacological mechanism involved as one being related to the Ro 15-1788-sensitive benzodiazepine (Bzd) recognition site(s) of the GABA receptor complex. RESUME: La taille du champ receptif des neurones corticaux SI est modifiee par la methaqualone via un mecanisme gabaergique La methaqualone (Mtq; quaaludes ou Tudes) est une substance controiee qui a une structure moleculaire reliee aux drogues de la famille des imidiazobenzodiazepines et qui a acquis une certaine notoriete recem- ment a cause d'abus largement repandus chez les usagers de drogues. lis rapportent eprouver des paresthesies peripheriques et des engourdissements transitoires des parties du corps pourvues d'une innervation cutanee dense (les levres, le bout des doigts etc.). Comme la taille du champ receptif de plusieurs neurones corticaux somesthesiques pri- maires (SI) est controiee par des processus inhibiteurs dont la mediation se fait par I'acide gamma-aminobutyrique (GABA), nous avons verifie si les symptomes cliniques de la Mtq pourraient etre en relation avec un mode d'action faisant appel aux processus synaptiques centraux a mediation GABAergique. -

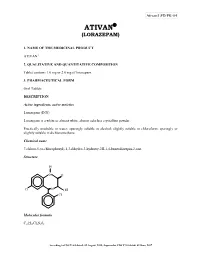

Ativan/LPD/PK-04 ATIVAN (LORAZEPAM)

Ativan/LPD/PK-04 ATIVAN (LORAZEPAM) 1. NAME OF THE MEDICINAL PRODUCT ATIVAN 2. QUALITATIVE AND QUANTITATIVE COMPOSITION Tablet contains 1.0 mg or 2.0 mg of lorazepam. 3. PHARMACEUTICAL FORM Oral Tablets DESCRIPTION Active ingredients, active moieties Lorazepam (INN) Lorazepam is a white or almost white, almost odorless crystalline powder. Practically insoluble in water; sparingly soluble in alcohol; slightly soluble in chloroform; sparingly or slightly soluble in dichloromethane. Chemical name 7-chloro-5-(o-chlorophenyl)-1,3-dihydro-3-hydroxy-2H-1,4-benzodiazepin-2-one. Structure H N O Cl N OH Cl Molecular formula C15H10Cl2N202 According to CDS V 6.0 dated: 02 August, 2018; Supersedes CDS V 5.0 dated: 02 June, 2017 Ativan/LPD/PK-04 Molecular weight 321.2 4. CLINICAL PARTICULARS 4.1. THERAPEUTIC INDICATIONS Short-term management of anxiety disorders, including the following: - Short-term relief of symptoms of anxiety - Generalized anxiety disorders - Anxiety in psychotic states - Anxiety associated with somatic symptoms - Anxiety associated with depression or depressive symptoms - Reactive anxiety Insomnia associated with anxiety Alcohol withdrawal Prevention of delirium tremens Surgical premedication Adjunctive therapy to standard antiemetic drugs for the prophylactic and symptomatic treatment of nausea and vomiting associated with cancer chemotherapy 4.2. POSOLOGY AND METHOD OF ADMINISTRATION Dosage and duration of therapy should be individualized. The lowest effective dose should be prescribed for the shortest duration possible. The risk of withdrawal and rebound phenomena is greater after abrupt discontinuation; therefore, the drug should be discontinued gradually (See section 4.4. Special warnings and precautions for use). Extension of the treatment period should not take place without re-evaluation of the need for continued therapy. -

The Effect of Ethanol on Residual Plasma Methaqualone Concentrations and Behaviour in Volunteers Who Have Taken Mandrax

Br. J. clin. Pharmac. (1977), 4 LETTERS TO THE EDITORS 245 In conclusion, butriptyline produces mild HARTMANN, E. & CRAVENS, J. (1973). Long-term sedation and promotes sleep, but it is also possible drug effects on human sleep. In Sleep, ed. Koella, W.P. to detect a sleep-disturbing action of a type found & Levin, P., pp. 477-485. Basel: S. Karger. with other tricyclic drugs. Compared with other JARAMILLO, J. & GREENBERG, R. (1975). Com- parative pharmacological studies on butriptyline and related drugs butriptyline causes less unpleasant some related standard tricycic antidepressants. Can. J. subjective effects. PhysioL Pharmac., 53, 104-112. MILLER, R.G. (1966). Simultaneous Statistical Inference. VLASTA BREZINOVA, SHARON BORROW, I. New York: McGraw-Hill. OSWALD & DOROTHY ROBINSON OSWALD, I. LEWIS, S.A., DUNLEAVY, D., BREZINOVA, V. & BRIGGS, M. (1971). Drugs of University Department of Psychiatry, Royal dependence though not of abuse: fenfluramine and Edinburgh Hospital, Morningside Park, Edinburgh imipramine. Br. med. J., 3, 70-73. EH10 SHF, Scotland OSWALD, I., BkEZINOVA, V. & DUNLEAVY, D. (1972). On the slowness of action of tricyclic Received October 4, 1976 antidepressant drugs. Br. J. Psychiat., 120, 673-677. PUGSLEY, T.A. & LIPPMANN, W. (1974). Effect of butriptyline on the brain uptake mechanisms for noradrenaline and 5-hydroxytryptamine. J. Pharm. References Pharmac., 26, 778-782. RECHTSCHAFFEN, A. & KALES, A. (1968). A Manual DUNLEAVY, D., BkEZINOVA, V., OSWALD, I., of Standardized Terminology, Techniques and Scoring MACLEAN, A. & TINKER, M. (1972). Changes System for Sleep Stages of Human Subjects. Washing- during weeks in effects of tricyclic drugs on the ton, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, N.I.H. -

South Carolina Drug Statutes

South Carolina Drug Statutes South Carolina Code of Laws: Title 44 Health Code SCHEDULE CRITERIA AND OFFENSES/PENALTIES ENHANCEMENTS/BENEFIT COMPOSITION 44-53-370 RESTRICTIONS SCHEDULE I: (b)(1) Manufacture, offense: 5-30yrs and/or (a) A high potential for abuse; distribution, purchase or <$50,000 (b) No accepted medical use in possess w/ intent (p.w.i.) or subsequent offense: 10- treatment in the United States; Schedule I(b)&(c) narcotics, 30yrs and/or <$50,000 (c) A lack of accepted safety for LSD, Schedule II narcotics use in treatment under medical Felony: <15yrs and/or eligible for s.s. and p.p. if or supervision. <$25,000 offense, or offense (and priors S.C. Code Ann. § 44-53-180 were possession convictions) (B) Opiates: E.g., difenoxin (b)(2) Manufacture, offense: <10yrs and/or (C) Opium derivatives: E.g., distribution, p.w.i. <$10,000 heroin, codeine compounds, Other Schedule I, II, or III, or subsequent offense: 5- morphine compounds, etc. flunitrazepam or analogues 20yrs and/or <$20,000 (D) Hallucinogenic Felony: <5yrs and/or <$5,000 substances: E.g., marijuana, (d)(4) Prima facie guilt of eligible for s.s. and p.p. if or MDMA, mescaline, DMT, Manufacture, distribution, offense, or offense (and priors peyote, LSD, psilocybin, THC, p.w.i. were possession convictions) synthetic cannabinoids, etc. Possession of more than: 1g of 44-53-460 Reduced sentence (E) Depressants: E.g., cocaine, 100mg of eucaine, for accommodation offense: Qualuudes, GHB 4grains of opium, 4grains of delivery/distribution was only (F) Stimulants: E.g., morphine, 2 grains of heroin, for accommodation to another fenethylline, MDPV, 100mg of isonipecaine, individual and not for profit or mephedrone 28g/1oz of marijuana, 10oz of to induce addiction S.C. -

CEDIA / DRI Drugs of Abuse Immunoassays 800-232-3342 |

Thermo Scientific CEDIA / DRI Drugs of Abuse Immunoassays 800-232-3342 | www.thermo.com/diagnostics % Excreted Major Compounds / Metabolites Detected in Generic Names Trade Names Appearance Street Names Route of Ingestion Half Life (hr) Progressive Symptomatology unchanged in Urine CEDIA® and DRI® Assays Hepatic Bud, pot, grass, hash, reefer, Mary D8THC-COOH, 11-0H D9THC, D9THC Altered perception, memory loss, disorientation, Cannabis, Marijuana, Hashish Marinol, Dronabinol Leaves, capsules, buds, liquid Smoked, oral 14-38 <1% excreted CANNABINOIDS Jane, weed, dope Glucuronide psychosis unchanged in urine BARBITURATES: Hepatic (A) .8-42 Amobarbital (A) (A) .1-3% Amytal, Nembutal, Butisol, (B1) .30-40 Butabarbital (B1) Blues, Blue Dolls, Rainbows, Yellows, (B1) .5-10% Amobarbital, Aprobarbital, Butethal, Sedation, anti-anxiety, euphoria, anesthesia, Decreased Luminal, Seconal, Tuinal, Capsule, powder, tablets, (B2) .30-40 Butalbital (B2) Nebbies, Barbs, Downers, Reds, Red Oral, injected (B2) .5% Butabarbital, Cyclopentobarbital, Butalbital, mental acuity and slowed speech, respiratory Fiorinal, Neodorm, solution (P) .15-48 Pentobarbital (P) Devils, Seccies (P) .1% Pentobarbital, Phenobarbital, Secobarbital depression, lethargy, stupor, coma Immenoctal, Stadadorm (Ph) .80-120 Phenobarbital (Ph) (Ph) .20-35% (S) .15-40 Secobarbital (S) (S) .5% BENZODIAZEPINE: (A) .7-13 Hepatic Alprazolam (A) (C1) .6-27 (A) .20% Chlordiazepoxide (C1) (C2) .30-40 (C1) .<1% Xanax, Librium, Valium, a-OH-alprazolam, Bromazepam, Chlorazepate, Clonazepam( C2) (C3) -

145677NCJRS.Pdf

,. "I ~- 1 _ .. If you have issues viewing or accessing this file• contact• us at NCJRS.gov.• a .~ .. A ~-.- .. , , , ... ,T:,: , I " 145677 • • U.S. Department of Justice National Institute of Justice This document has been reproduced exactly as received from the person or organization originating It. Points of vieW or opinions stated In this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the National Institute of Justice. Permission to reproduce this copyrighted material has been gra~~~ti tute for Substance Abuse Research to the National Criminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS). Further reproduction outside of the NCJRS system requires permission of the copyright owner. • " , '41!'~- • \..s " t CONTENTS Preface Quiz Parents Schools Marijuana Hashish Hashish Oil Opium Heroin Dilaudid ~2'1:>':'S-t'Jhm~·';"la"·~¥s'"r.':Jt,r;\;~)'!(,"iii,,';~,:j~'i:l;:i~;i~iJ\t:~.. ~~ ,,'~ - H :'" • i' b ":l,' ~~,,] .• :;<",,\/,,::'y,'.P\ '-1';;. ;;~'''1.W'··· .:'t''''';~'l;>;-·:t.lW;i~:\·~/~;~~;;;:~i·' ~ Cocaine Smoking Cocaine Amphetamines/Methamphetamines Clandestine LSD·25 PCP Mescaline Psilocybin· Psilocyn Mushrooms [4zTnhalants~'-',,-'~~--- ~~ Steroids Prescription Drugs Most Abused Designer Drugs The Look-alikes Alcohol Plus Other Drugs Warning Signs of Alcoholism Tobacco Smokeless Tobacco 65 Glossary of Slang Terms 67 References ~~~~~~~----------,.----- The following true story was related by Mrs. Chantal Devine, wife ofthe Honorable Grant Devine, Premier of Saskatchewan, at the PRIDE Canada National Conference on Youth and Drugs in May, 1988 in Ottawa. The story was told to Mrs. Devine by Father Lucien Larre, a priest in Saskatchewan and a founder of Bosco Homes, a home for delinquent boys. -

483 Administrative Records, Texas Department of Criminal Justice

Consistent with the terms of the Court’s May 22, 2017 scheduling order, the record has been redacted for all information that plaintiff, Texas Department of Criminal Justice (Texas), has identified as confidential. In addition, Defendants have also redacted information that the drug’s supplier and broker have separately advised the agency they consider confidential and private, as well as information the agency itself generally treats as confidential. This information has been redacted pending final FDA’s review of confidentiality claims, and our filing of the record with these redactions does not necessarily reflect our agreement with all of the claims of confidentiality Defendants have received. Defendants explicitly reserve the right to make an independent determination regarding the proper scope of redactions at a later time. Should we identify any of Texas’s redactions that are over-broad or otherwise improper, we will work with Texas’s counsel to revise the redactions in the record. Exhibit 14 FDA 095 Case 1:11-cv-00289-RJL Document 13-3 Filed 04/20/11 Page 1 of 74 CERTJFICATE Pursuant to the provisions ofRule 44 ofthe Federal Rules ofCivil Procedure, I hereby certifY that John Verbeten, Director ofthe Operations and Policy Branch, Division of Import Operations and Policy, Office ofRegional Operations, Office ofRegulatory Affairs, United States Food and Drug Administration, whose declaration is attached, has custody ofofficial records ofthe United States Food and Drug Administration. In witness whereof, I have, pursuant to the provision ofTitle 42, United States Code, Section 3505, and FDA StaffManual Guide 1410.23, hereto set my hand and caused the seal ofthe Department ofHealth and Human Services to be affixed th.is ~oi{.