483 Administrative Records, Texas Department of Criminal Justice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Metabolic-Hydroxy and Carboxy Functionalization of Alkyl Moieties in Drug Molecules: Prediction of Structure Influence and Pharmacologic Activity

molecules Review Metabolic-Hydroxy and Carboxy Functionalization of Alkyl Moieties in Drug Molecules: Prediction of Structure Influence and Pharmacologic Activity Babiker M. El-Haj 1,* and Samrein B.M. Ahmed 2 1 Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences, University of Science and Technology of Fujairah, Fufairah 00971, UAE 2 College of Medicine, Sharjah Institute for Medical Research, University of Sharjah, Sharjah 00971, UAE; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 6 February 2020; Accepted: 7 April 2020; Published: 22 April 2020 Abstract: Alkyl moieties—open chain or cyclic, linear, or branched—are common in drug molecules. The hydrophobicity of alkyl moieties in drug molecules is modified by metabolic hydroxy functionalization via free-radical intermediates to give primary, secondary, or tertiary alcohols depending on the class of the substrate carbon. The hydroxymethyl groups resulting from the functionalization of methyl groups are mostly oxidized further to carboxyl groups to give carboxy metabolites. As observed from the surveyed cases in this review, hydroxy functionalization leads to loss, attenuation, or retention of pharmacologic activity with respect to the parent drug. On the other hand, carboxy functionalization leads to a loss of activity with the exception of only a few cases in which activity is retained. The exceptions are those groups in which the carboxy functionalization occurs at a position distant from a well-defined primary pharmacophore. Some hydroxy metabolites, which are equiactive with their parent drugs, have been developed into ester prodrugs while carboxy metabolites, which are equiactive to their parent drugs, have been developed into drugs as per se. -

Date Rape and Steroid Panels, Updated Feb 1 2010

DRUG-FACILITATED SEXUAL ASSAULT (aka “DATE RAPE”) AND STEROID PANELS (Effective January 26, 2010) Basic Date Rape Panel Comprehensive Date Rape Panel • GHB (Hair Only) • Ketamine • GHB • Benzodiazepines, including Rohypnol • Benzodiazepines Alprazolam Clonazepam Alprazolam Clonazepam Diazepam Flunitrazepam (Rohypnol) Diazepam Flunitrazepam Lorazepam Oxazepam Lorazepam Oxazepam Temazepam Nitrazepam Temazepam Nitrazepam • Opioids Codeine Hydrocodone Comprehensive Date Rape Panel Meperidine Tramadol (Urine Only) Methadone Fentanyl • GHB • Sedatives/Hypnotics Ketamine Methaqualone • Barbiturates Zolpidem Zopiclone Amobarbital Butalbital Pentobarbital Phenobarbital • Over-The-Counter Drugs Secobarbital Diphenhydramine Dextromethorphan Doxylamine Chlorpheniramine • Benzodiazepines Brompheniramine Promethazine Alprazolam Clonazepam Pheniramine Diazepam Flunitrazepam Lorazepam Oxazepam • Muscle Relaxants Temazepam Nitrazepam Carisoprodol Meprobamate • Opioids Cyclobenzaprine Methocarbamol Codeine Morphine • Hallucinogens (PCP) Hydrocodone Hydromorphone Oxycodone Oxymorphone Meperidine Tramadol ANABOLIC STEROID PANEL Methadone Fentanyl (Urine or Blood) Propoxyphene Buprenorphine Androstenedione Boldenone • Sedatives/Hypnotics Fluoxymesterolone Mesterolone Ketamine Methaqualone 17-a-Methyltestosterone Methenolone Zolpidem Zopiclone Methandrostenolone Nandrolone • Over-The-Counter Drugs Norethandrolone Oxandrolone Diphenhydramine Dextromethorphan Stanozolol Trenbolone Doxylamine Chlorpheniramine Brompheniramine Promethazine Pheniramine For additional steroids, • Muscle Relaxants call for details and pricing Carisoprodol Meprobamate EXPERTOX, INC. Cyclobenzaprine Methocarbamol Blood should only be 1803 CENTER STREET, SUITE A submitted for date rape • Hallucinogens DEER PARK, TX 77536 PCP MDMA panels if within five (5) hours of 281.476.4600 MDA MDEA ingestion. FAX 281.930.8856 Cannabinoids (Carboxy-THC) • WWW.EXPERTOX.COM Turaround Time: Ten (10) Urine must be collected within five (5) days business days from specimen of drug exposure receipt at the lab . -

Determination of Barbiturates and 11-Nor-9-Carboxy-Δ9-THC in Urine

Determination of Barbiturates and 11-Nor-9-carboxy- 9-THC in Urine using Automated Disposable Pipette Extraction (DPX) and LC/MS/MS Fred D. Foster, Oscar G. Cabrices, John R. Stuff, Edward A. Pfannkoch GERSTEL, Inc., 701 Digital Dr. Suite J, Linthicum, MD 21090, USA William E. Brewer Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of South Carolina, 631 Sumter St. Columbia, SC 29208, USA KEYWORDS DPX, LC/MS/MS, Sample Preparation, High Throughput Lab Automation ABSTRACT This work demonstrates the use of disposable pipette extraction (DPX) as a fast and automated sample preparation technique for the determination of barbiturates and 11-nor-9- carboxy- 9-THC (COOH-THC) in urine. Using a GERSTEL MultiPurpose Sampler (MPS) with DPX option coupled to an Agilent 6460 LC-MS/MS instrument, 8 barbiturates and COOH-THC were extracted and their concentrations determined. The resulting average cycle time of 7 min/ sample, including just-in-time sample preparation, enabled high throughput screening. Validation results show that the automated DPX-LC/ AppNote 1/2013 MS/MS screening method provides adequate sensitivity for all analytes and corresponding internal standards that were monitored. Lower limits of quantitation (LLOQ) were found to be 100 ng/mL for the barbiturates and 10 ng/mL for COOH-THC and % CVs were below 10 % in most cases. INTRODUCTION The continuously growing quantity of pain management sample extract for injection [1-2]. The extraction of the drugs used has increased the demand from toxicology Barbiturates and COOH-THC is based on the DPX-RP- laboratories for more reliable solutions to monitor S extraction method described in an earlier Application compliance in connection with substance abuse and/or Note detailing monitoring of 49 Pain Management diversion. -

)&F1y3x PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX to THE

)&f1y3X PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE HARMONIZED TARIFF SCHEDULE )&f1y3X PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE TARIFF SCHEDULE 3 Table 1. This table enumerates products described by International Non-proprietary Names (INN) which shall be entered free of duty under general note 13 to the tariff schedule. The Chemical Abstracts Service (CAS) registry numbers also set forth in this table are included to assist in the identification of the products concerned. For purposes of the tariff schedule, any references to a product enumerated in this table includes such product by whatever name known. Product CAS No. Product CAS No. ABAMECTIN 65195-55-3 ACTODIGIN 36983-69-4 ABANOQUIL 90402-40-7 ADAFENOXATE 82168-26-1 ABCIXIMAB 143653-53-6 ADAMEXINE 54785-02-3 ABECARNIL 111841-85-1 ADAPALENE 106685-40-9 ABITESARTAN 137882-98-5 ADAPROLOL 101479-70-3 ABLUKAST 96566-25-5 ADATANSERIN 127266-56-2 ABUNIDAZOLE 91017-58-2 ADEFOVIR 106941-25-7 ACADESINE 2627-69-2 ADELMIDROL 1675-66-7 ACAMPROSATE 77337-76-9 ADEMETIONINE 17176-17-9 ACAPRAZINE 55485-20-6 ADENOSINE PHOSPHATE 61-19-8 ACARBOSE 56180-94-0 ADIBENDAN 100510-33-6 ACEBROCHOL 514-50-1 ADICILLIN 525-94-0 ACEBURIC ACID 26976-72-7 ADIMOLOL 78459-19-5 ACEBUTOLOL 37517-30-9 ADINAZOLAM 37115-32-5 ACECAINIDE 32795-44-1 ADIPHENINE 64-95-9 ACECARBROMAL 77-66-7 ADIPIODONE 606-17-7 ACECLIDINE 827-61-2 ADITEREN 56066-19-4 ACECLOFENAC 89796-99-6 ADITOPRIM 56066-63-8 ACEDAPSONE 77-46-3 ADOSOPINE 88124-26-9 ACEDIASULFONE SODIUM 127-60-6 ADOZELESIN 110314-48-2 ACEDOBEN 556-08-1 ADRAFINIL 63547-13-7 ACEFLURANOL 80595-73-9 ADRENALONE -

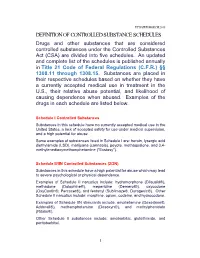

Definition of Controlled Substance Schedules

UPDATED MARCH 2018 DEFINITION OF CONTROLLED SUBSTANCE SCHEDULES Drugs and other substances that are considered controlled substances under the Controlled Substances Act (CSA) are divided into five schedules. An updated and complete list of the schedules is published annually in Title 21 Code of Federal Regulations (C.F.R.) §§ 1308.11 through 1308.15. Substances are placed in their respective schedules based on whether they have a currently accepted medical use in treatment in the U.S., their relative abuse potential, and likelihood of causing dependence when abused. Examples of the drugs in each schedule are listed below. Schedule I Controlled Substances Substances in this schedule have no currently accepted medical use in the United States, a lack of accepted safety for use under medical supervision, and a high potential for abuse. Some examples of substances listed in Schedule I are: heroin, lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), marijuana (cannabis), peyote, methaqualone, and 3,4- methylenedioxymethamphetamine ("Ecstasy"). Schedule II/IIN Controlled Substances (2/2N) Substances in this schedule have a high potential for abuse which may lead to severe psychological or physical dependence. Examples of Schedule II narcotics include: hydromorphone (Dilaudid®), methadone (Dolophine®), meperidine (Demerol®), oxycodone (OxyContin®, Percocet®), and fentanyl (Sublimaze®, Duragesic®). Other Schedule II narcotics include: morphine, opium, codeine, and hydrocodone. Examples of Schedule IIN stimulants include: amphetamine (Dexedrine®, Adderall®), methamphetamine (Desoxyn®), and methylphenidate (Ritalin®). Other Schedule II substances include: amobarbital, glutethimide, and pentobarbital. 1 Schedule III/IIIN Controlled Substances (3/3N) Substances in this schedule have a potential for abuse less than substances in Schedules I or II and abuse may lead to moderate or low physical dependence or high psychological dependence. -

Anesthesia: the Good, the Bad, and the Elderly

ANESTHESIA: THE GOOD, THE BAD, AND THE ELDERLY Item Type Electronic Thesis; text Authors Hansen, Madeline Citation Hansen, Madeline. (2020). ANESTHESIA: THE GOOD, THE BAD, AND THE ELDERLY (Bachelor's thesis, University of Arizona, Tucson, USA). Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 25/09/2021 08:05:26 Item License http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/InC/1.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/651023 ANESTHESIA: THE GOOD, THE BAD, AND THE ELDERLY By MADELINE JOLLEEN HANSEN ____________________ A Thesis Submitted to The Honors College In Partial Fulfillment of the Bachelors degree With Honors in Physiology THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA M A Y 2 0 2 0 Approved by: ____________________________ Dr. Zoe Cohen Department of Physiology Table of Contents Page number(s) Abstract……………………………………………………………………………………………………..2 General History of Anesthesia.………………………………………………………………………….3-14 Prehistoric-200AD…………………………………………………………….………………....3-5 200AD- 1846 (historical surgery)…………………….………………………………………….5-8 1847-1992……………………...…………………….……………………………………...….9-14 Physiology of General Anesthesia………………………………………………………...…………...14-16 Understanding of anesthesia mechanism…………………………………………………………14 System impacts………………………………………………………………………………..15-16 Description -

And Calcium, Magnesium, Potassium and Sodium Oxybates (Xywav™)

Louisiana Medicaid Sodium Oxybate (Xyrem®) and Calcium, Magnesium, Potassium and Sodium Oxybates (Xywav™) The Louisiana Uniform Prescription Drug Prior Authorization Form should be utilized to request clinical authorization for sodium oxybate (Xyrem®) and calcium, magnesium, potassium and sodium oxybates (Xywav™). These agents have Black Box Warnings and are subject to Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) under FDA safety regulations. Please refer to individual prescribing information for details. Approval Criteria • The recipient is 7 years of age or older on date of request; AND • The recipient has a documented diagnosis of narcolepsy or cataplexy; AND • The prescribing provider is a Board-Certified Neurologist or a Board-Certified Sleep Medicine Physician; AND • By submitting the authorization request, the prescriber attests to the following: o The prescribing information for the requested medication has been thoroughly reviewed, including any Black Box Warning, Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS), contraindications, minimum age requirements, recommended dosing, and prior treatment requirements; AND o All laboratory testing and clinical monitoring recommended in the product prescribing information have been completed as of the date of the request and will be repeated as recommended; AND o The recipient has no inappropriate concomitant drug therapies or disease states. Duration of initial authorization approval: 3 months Reauthorization Criteria • The recipient continues to meet all initial approval criteria; AND -

Prescription Drug Management

Check out our new site: www.acllaboratories.com Prescription Drug Management Non Adherence, Drug Misuse, Increased Healthcare Costs Reports from the Centers for DiseasePrescription Control and Prevention (CDC) say Drug deaths from Managementmedication overdose have risen for 11 straight years. In 2008 more than 36,000 people died from drug overdoses, and most of these deaths were caused by prescription Nondrugs. Adherence,1 Drug Misuse, Increased Healthcare Costs The CDC analysis found that nearly 40,000 drug overdose deaths were reported in 2010. Prescribed medication accounted for almost 60 percent of the fatalities—far more than deaths from illegal street drugs. Abuse of painkillers like ReportsOxyContin from and the VicodinCenters forwere Disease linked Control to the and majority Prevention of the (CDC) deaths, say deaths from according to the report.1 medication overdose have risen for 11 straight years. In 2008 more than 36,000 people died from drug overdoses, and most of these deaths were caused by prescription drugs. 1 A health economics study analyzed managed care claims of more than 18 million patients, finding that patients undergoing opioid therapyThe CDCfor chronic analysis pain found who that may nearly not 40,000 be following drug overdose their prescription deaths were regimenreported in 2010. Prescribed medication accounted for almost 60 percent of the fatalities—far more than deaths have significantly higher overall healthcare costs. from illegal street drugs. Abuse of painkillers like OxyContin and Vicodin were linked to the majority of the deaths, according to the report.1 ACL offers drug management testing to provide information that can aid clinicians in therapy and monitoring to help improve patientA health outcomes. -

Smumedical Journal

SMU Medical Journal ISSN : 2349 – 1604 (Volume – 4, No. 1, January 2017) Review Article Indexed in SIS (USA), ASI (Germany), I2OR & i-Scholar (India), SJIF (Morocco) and Cosmos Foundation (Germany) databases. Impact Factor: 3.835 (SJIF) Analytical Aspects with Brief Overview of Depressants Sandeep Kumar1 Nand Gopal Giri2 Ashok Kumar Jaiswal3* Anil Kumar Jaiswal4 1M.Sc. (Forensic Science), LNJN NICFS, New Delhi 110085, 2Assistant Professor, Department of Chemistry, Shivaji College (University of Delhi) Raja Garden, New Delhi 110 027, 3Dept. of Forensic Medicine and toxicology, All India institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi 110 029.4Assistant Professor, Department of Mathematics, St. Andrew’s PG College, Gorakhpur, UP. *Corresponding author Manuscript received : 30.10.2016 Manuscript accepted: 21.11.2016 Abstract Depressants are drugs that slow down the functions of the central nervous system (CNS). These drugs are used to reduce anxiety and insomnia without drowsiness. The depressants cause relaxed feeling if used in small quantity but cause unconsciousness, vomiting and even death if taken in high quantity. It affects concentration and coordination of a person by slowing down his/ her ability to respond in unexpected situations. These drugs are also attributed for their physiological and psychological effects, eventually in large dose it become lethal. The different 142 SMU Medical Journal, Volume – 4, No. – 1, January, 2017 physical and chemical features of some very often used depressants are discussed in this manuscript. Keyword: Depressant, TLC, UV spectroscopy, HPLC, GLC etc. Introduction The classical depressants are hypnotics (which induce sleep), most antianxiety medicine (diazepam or valium), muscle spasm prevent seizure, but these drugs rapidly develop dependence and tolerance which finally leads to coma and death, so use of these drugs is highly unsafe. -

Familial Mediterranean Fever

:: Familial Mediterranean fever – This document is a translation of the French recommendations drafted by Prof Gilles Grateau, Dr Véronique Hentgen, Dr Katia Stankovic Stojanovic and Dr Gilles Bagou reviewed and published by Orphanet in 2010. – Some of the procedures mentioned, particularly drug treatments, may not be validated in the country where you practice. Synonyms: Periodic disease, FMF Definition: Familial Mediterranean fever (FMF) is an auto-inflammatory disease of genetic origin, affecting Mediterranean populations and characterised by recurrent attacks of fever accompanied by polyserositis that causes the symptoms. Colchicine is the basic reference treatment and is designed to tackle inflammatory attacks and prevent amyloidosis, the most severe complication of FMF. Further information: See the Orphanet abstract http://www.orpha.net/data/patho/Pro/en/Emergency_FamilialMediterraneanFever-enPro920.pdf ©Orphanet UK 1/5 Pre-hospital emergency care recommendations Call for a patient suffering from Familial mediterranean fever Synonyms periodic disease FMF Mechanisms auto-inflammatory disease that affects Mediterranean populations in particular, due to mutation of the MEFV gene that codes pyrin or marenostrin, this being the underlying cause of congenital immune dysfunction; repeated inflammatory attacks can lead to amyloidosis, particularly renal Specific risks in emergency situations acute inflammatory attack, particularly abdominal (pseudo-surgical), but also thoracic, articular (knees) or testicular fever as an expression -

Intravenous Anesthetics a Drug That Induces Reversible Anesthesia the State of Loss of Sensations, Or Awareness

DR.MED. ABDELKARIM ALOWEIDI AL-ABBADI ASSOCIATE PROF. FACULTY OF MEDICINE THE UNIVERSITY OF JORDAN Goals of General Anesthesia Hypnosis (unconsciousness) Amnesia Analgesia Immobility/decreased muscle tone (relaxation of skeletal muscle) Reduction of certain autonomic reflexes (gag reflex, tachycardia, vasoconstriction) Intravenous Anesthetics A drug that induces reversible anesthesia The state of loss of sensations, or awareness. Either stimulates an inhibitory neuron, or inhibits an excitatory neuron. Organs are divided according to blood perfusion: High- perfusion organs (vessel-rich); brain takes up disproportionately large amount of drug compared to less perfused areas (muscles, fat, and vessel-poor groups). After IV injection, vessel-rich group takes most of the available drug Drugs bound to plasma proteins are unavailable for uptake by an organ After highly perfused organs are saturated during initial distribution, the greater mass of the less perfused organs continue to take up drug from the bloodstream. As plasma concentration falls, some drug leaves the highly perfused organs to maintain equilibrium. This redistribution from the vessel-rich group is responsible for termination of effect of many anesthetic drugs. Compartment Model Inhibitory channels : GABA-A channels ( the main inhibitory receptor). Glycine channels. Excitatory channels : Neuronal nicotic. NMDA. Rapid onset (mainly unionized at physiological pH) High lipid solubility Rapid recovery, no accumulation during prolonged infusion Analgesic -

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 300 697 CG 021 192 AUTHOR Gougelet, Robert M.; Nelson, E. Don TITLE Alcohol and Other Chemicals. Adolescent A

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 300 697 CG 021 192 AUTHOR Gougelet, Robert M.; Nelson, E. Don TITLE Alcohol and Other Chemicals. Adolescent Alcoholism: Recognizing, Intervening, and Treating Series No. 6. INSTITUTION Ohio State Univ., Columbus. Dept. of Family Medicine. SPONS AGENCY Health Resources and Services Administration (DHHS/PHS), Rockville, MD. Bureau of Health Professions. PUB DATE 87 CONTRACT 240-83-0094 NOTE 30p.; For other guides in this series, see CG 021 187-193. AVAILABLE FROMDepartment of Family Medicine, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH 43210 ($5.00 each, set of seven, $25.00; audiocassette of series, $15.00; set of four videotapes keyed to guides, $165.00 half-inch tape, $225.00 three-quarter inch tape; all orders prepaid). PUB TYPE Guides - Classroom Use - Materials (For Learner) (051) -- Reports - General (140) EDRS PRICE MF01 Plus Plstage. PC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS *Adolescents; *Alcoholism; *Clinical Diagnosis; *Drug Use; *Family Problems; Physician Patient Relationship; *Physicians; Substance Abuse; Units of Study ABSTRACT This document is one of seven publications contained in a series of materials for physicians on recognizing, intervening with, and treating adolescent alcoholism. The materials in this unit of study are designed to help the physician know the different classes of drugs, recognize common presenting symptoms of drug overdose, and place use and abuse in context. To do this, drug characteristics and pathophysiological and psychological effects of drugs are examined as they relate to administration,