Final Plan of Management: Lane Cove National Park

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Figure S1: Map of Sydney Harbour and the Position of the Hawkesbury and Georges Rivers

10.1071/MF09263_AC © CSIRO 2010 Marine and Freshwater Research 2010, 61(10), 1109–1122 Figure S1: Map of Sydney Harbour and the position of the Hawkesbury and Georges Rivers. Circles and diamonds indicate locations sampled in the Parramatta and Lane Cover Rivers, respectively. Running east to west, the locations within the Parramatta River were: Iron Cove (33°52'14"S 151° 9'2"E), Five Dock Bay (33°51'10"S 151° 8'32"E), Hen and Chicken Bay (33°51'37"S 151° 7'7"E), Morrisons Bay (33°49'49"S 151° 6'43"E), Majors Bay (33°50'33"S 151° 6'4"E), Brays Bay (33°49'53"S 151° 5'33"E) and Duck Creek (33°49'49"S 151° 6'4"E). Running north to south, the locations within the Lane Cove river were: Field of Mars (33°49'3"S 151° 8'35"E), Boronia Park (33°49'37"S 151° 8'38"E), Tambourine Bay (33°49'43"S 151° 9'40"E) and Woodford Bay (33°49'51"S 151°10'24"E). The coordinates for the locations within the other estuaries were: Hawkesbury River (Cogra Bay 33°31'23"S 151°13'23"E; Porto Bay Bay 33°33'51"S 151°13'17"E) and Georges River (Kyle Bay 33°59'28"S 151° 6'8"E and Coronation Bay 33°59'54"S 151° 4'38"E). 10.1071/MF09263_AC © CSIRO 2010 Marine and Freshwater Research 2010, 61(10), 1109–1122 Table S1. Organic contaminants analysed in sediments Class LOD, mg/kg Method Specific chemicals or fractions Polycyclic aromatic 0.01 USEPA methods Naphthalene, acenaphthylene, acenaphthene, fluorene, hydrocarbons (PAHs) 3550/8270 phenanthrene, anthracene, fluoranthene, pyrene, benz(a)anthracene, chrysene, benzo(b)-fluoranthene, benzo(k)-fluoranthene, benzo(a)pyrene, indeno(1,2,3- cd)pyrene, dibenz(ah)anthracene, and benzo(ghi)perylene). -

The Friends of Lane Cove National Park Help Support Their Work and Keep in Touch with Happenings in the Park

How to Help FAIRYLAND Lane Cove National Park There is plenty to do and opportunities for all, Individuals, Groups or Companies. Bushcare is great way of learning more about your local environment while helping to preserve it for future generations. Ideal for one off corporate or community days, or regular monthly sessions. Join with The Friends of Lane Cove National Park Help support their work and keep in touch with happenings in the park Find out more at www.friendsoflanecovenationalpark.org.au Contact us at [email protected] or speak to the Lane Cove National Park Volunteer Bushcare Co-ordinator 0419 753 806 Produced by Friends of Lane Cove National Park With assistance from Sydney Metropolitan Catchment Management Authority and The Australian Government’s Caring for 0ur Country Program History, Heritage and Ecology Where Threats Situated right next to one of the fastest growing commercial centres in Weeds are a major threat in this as in Sydney, less than 3 kilometres from Chatswood and less than 10 kilometres so many other areas. Most of the local soils are derived from from the centre of Sydney is Fairyland, part of Lane Cove National Park. sandstone and are very low in nutrients. The almost 42 hectares of bushland sandwiched between Delhi Road and Surprisingly this has resulted in a great the Lane Cove River provides a home for endangered species including diversity of plants that have adapted to Powerful Owls, and other species such these conditions. Weeds, mainly plants as Echidnas which, while not on the en- from overseas, generally gain a foothold dangered list, are extremely uncommon when ’man’ has disturbed the soil and changed conditions, this can often be this close to the centre of a major city. -

Estuary Surveillance for QX Disease

Estuary surveillance Student task sheet for QX disease The following tables show data collected Estuary Surveillance 2002: during estuary surveillance from 2001– During the 2002 sampling period a total of 2004 for New South Wales and 5250 oysters were received and processed Queensland. N is the number of oysters from 18 NSW estuaries and three tested in a random sample of the oyster Queensland zones using tissue imprints. population. Dr Adlard used two methods of disease detection in surveillance — tissue imprint and PCR. Table 2A: Tissue imprints used to detect the QX disease parasite Estuary Surveillance 2001: 2002 Survey results Table 1: Tissue imprint results for 2001 N 2001 Survey Results Estuary N infected % N Northern Moreton Bay 250 0 0 Estuary N infected % Central Moreton Bay 250 0 0 Tweed River 316 0 0 Southern Moreton Bay 250 2 0.8 Brunswick River 320 0 0 Tweed River 250 0 0 Richmond River 248 0 0 Brunswick River 250 0 0 Clarence River 330 5 1.52 Richmond River 250 102 40.8 Wooli River 294 0 0 Clarence River 250 55 22 Kalang /Bellinger 295 0 0 Wooli River 250 0 0 Rivers Kalang /Bellingen Rivers 250 0 0 Macleay River 261 0 0 Macleay River 250 0 0 Hastings River 330 0 0 Hastings River 250 0 0 Manning River 286 0 0 Manning River 250 0 0 Wallis Lakes 271 0 0 Wallis Lakes 250 0 0 Port Stephens 263 0 0 Port Stephens 250 0 0 Hawkesbury River 323 0 0 Hawkesbury River 250 0 0 Georges River 260 123 47.31 Georges River 250 40 16 Shoalhaven/ 255 0 0 Crookhaven Shoalhaven/Crookhaven 250 0 0 Bateman's Bay 300 0 0 Bateman's Bay 250 0 0 Tuross Lake 304 0 0 Tuross Lake 250 0 0 Narooma 300 0 0 Narooma 250 0 0 Merimbula 250 0 0 Merimbula 250 0 0 © Queensland Museum 2006 Table 2B: PCR results from 2002 on Estuary Surveillance 2003: oysters which had tested negative to QX During 2003 a total of 4450 oysters were disease parasite using tissue imprints received and processed from 22 NSW estuaries and three Queensland zones. -

De Burghs Bridge to Fullers Bridge (Darug Country)

De Burghs Bridge to Fullers Bridge (Darug Country) 1 h 30 min to 2 h 30 min 4 5.7 km ↑ 121 m Hard track One way ↓ 149 m Following the Lane Cove River, this walk mostly follows a section of the Great North Walk and is well maintained and signposted. Things to lookout for include Fiddens Wharf which is a very pleasant spot to sit and watch the ducks. The walk passes by Lane Cove National Park Headquarters, so pop by and check out the other experiences available in the park. Let us begin by acknowledging the Darug people, Traditional Custodians of the land on which we travel today, and pay our respects to their Elders past and present. 240 192 144 96 48 0 0 m 4 km 2 km 285 m 570 m 850 m 1.1 km 1.7 km 2.3 km 2.5 km 2.8 km 3.1 km 3.4 km 3.7 km 4.2 km 4.5 km 4.8 km 5.1 km 5.4 km 5.7 km 5.9x 1.4 km Class 4 of 6 Rough track, where fallen trees and other obstacles are likely Quality of track Rough track, where fallen trees and other obstacles are likely (4/6) Gradient Short steep hills (3/6) Signage Directional signs along the way (3/6) Infrastructure Limited facilities, not all cliffs are fenced (3/6) Experience Required Some bushwalking experience recommended (3/6) Weather Storms may impact on navigation and safety (3/6) Getting to the start: From Lane Cove Road Exit Turn on to Lane Cove Road Exit then drive for 30 m Continue onto Lane Cove Road Exit and drive for another 45 m Turn right onto Lane Cove Road, A3 and drive for another 1.9 km Before you start any journey ensure you; • Tell someone you trust where you are going and what to do if you are late returning • Have adequate equipment, supplies, skills & knowledge to undertake this journey safely • Consider weather forecasts, park/track closures & fire dangers • Can respond to emergencies & call for help at any point • Are healthy and fit enough for this journey Share If not, change plans and stay safe. -

Hawk Cafe Ideas Sheet

The Great Outdoors Open the door - it is right outside! BACKYARDS IDEAS • Make a frog play pond ...or a fish pond.....in a dish - make sure you have a toy frog or fish first! • Make a fairy/dinosaur garden in a large dish using leaves, flowers moss, pebbles, sand, dirt, grass, plastic dino's • Read Wombat Stew and go and make one in old pots and pans • Create a waterfall - are great on a hot day • Play in a shallow tray of water with boats • Paint pictures on the paving or fence with water and big brushes • Draw on the paving with chalk - have a theme - pirate island, crocodile creek, fairy dell • Imagine - make a boat out of a laundry basket, house out of a large box • The sandpit - one day it is a beach, the next an island. • Make a "Science Box" - explore the garden - look for bugs, look in mulch under leaves of trees, find spiders in webs, search for the spider when the web is empty. • Scavenger hunt - find things different shapes, things beginning with each letter of the alphabet • Search for a rainbow - rainbow game - collect some paint swatches from your favourite hardware or painting store and find things in the garden the same colour. • Cubbies houses/tents and tee-pees. - as Kids get older graduate from the Pop up tents to constructing their own tents. Give them a tarp, some rope and tent pegs....let them see what they can do....Keep watch and let them have a go - jump in to help just before they give up in frustration or when they have tied each other up in the rope. -

Sunday 5 August

Sunday 5 August - 18th Sunday in Ordinary Time Holy Name Catholic Parish DIOCESE OF BROKEN BAY 35 Billyard Avenue Wahroonga 2076 Web l www.holynamewahroonga.com.au Welcome! A very warm welcome to anyone visiting our parish. It is good to have you with us. If you have any questions or would like to know more about our community at Holy Name please visit our parish website at www.holynamewahroonga.com.au. We hope you enjoy your time here at Holy Name Wahroonga. Please visit us again soon. CHARITABLE WORKS FUND - 2018-2019 The first of 3 appeals is this weekend. The Charitable Works Fund is 100% tax deductible and 98.25 cents of every dollar goes to the following five beneficiaries: CatholicCare Hospital Chaplaincy and Pastoral Care Practitioner Program – where five Pastoral Care Practitioners reach over 3,000 patients, 700 families and over 180 hospital staff each year across seven hospitals in our Diocese. Confraternity of Christian Doctrine – creating and updating the curriculum and training catechists who minister to public school students across the Diocese. St Lucy’s School – for primary school students with disabilities. St Edmund’s School – for secondary school students with disabilities. Ephpheta Centre – serving the Catholic deaf community. If you have an automatic donation in place through the Parish The next meeting of the Dominican Laity will be held in the Office, this will be processed on Monday, 6 August. Sunroom at 1 pm on Sunday the 12th August. All are welcome to attend. We seek to grow as a Welcoming and Inclusive -

Roads Thematic History

Roads and Maritime Services Roads Thematic History THIS PAGE LEFT INTENTIONALLY BLANK ROADS AND TRAFFIC AUTHORITY HERITAGE AND CONSERVATION REGISTER Thematic History Second Edition, 2006 RTA Heritage and Conservation Register – Thematic History – Second Edition 2006 ____________________________________________________________________________________ ROADS AND TRAFFIC AUTHORITY HERITAGE AND CONSERVATION REGISTER Thematic History Second Edition, 2006 Compiled for the Roads and Traffic Authority as the basis for its Heritage and Conservation (Section 170) Register Terry Kass Historian and Heritage Consultant 32 Jellicoe Street Lidcombe NSW, 2141 (02) 9749 4128 February 2006 ____________________________________________________________________________________ 2 RTA Heritage and Conservation Register – Thematic History – Second Edition 2006 ____________________________________________________________________________________ Cover illustration: Peak hour at Newcastle in 1945. Workers cycling to work join the main Maitland Road at the corner of Ferndale Street. Source: GPO1, ML, 36269 ____________________________________________________________________________________ 3 RTA Heritage and Conservation Register – Thematic History – Second Edition 2006 ____________________________________________________________________________________ Abbreviations DMR Department of Main Roads, 1932-89 DMT Department of Motor Transport, 1952-89 GPO1 Government Printer Photo Collection 1, Mitchell Library MRB Main Roads Board, 1925-32 SRNSW State Records of New South -

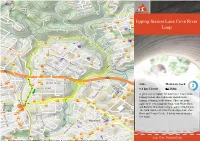

Epping Station Lane Cove River Loop

Epping Station Lane Cove River Loop 3 hrs Moderate track 3 8.4 km Circuit 168m A great way to explore the Lane Cove Valley from Epping Station, this walk loops around North Epping, returning to the station. There are many sights to be seen along this walk, with Whale Rock and Brown's Waterhole being a couple of highlights. The walk explores Devlins Creek, upper Lane Cove River and Terry's Creek. A lovely way to spend a few hours. 94m 30m Lane Cove National Park Maps, text & images are copyright wildwalks.com | Thanks to OSM, NASA and others for data used to generate some map layers. Big Ducky Waterhole Before You walk Grade The servicetrail loops around the top of the Big Ducky waterhole Bushwalking is fun and a wonderful way to enjoy our natural places. This walk has been graded using the AS 2156.1-2001. The overall and there is a nice rock overhang in which to break. Is also a popular Sometimes things go bad, with a bit of planning you can increase grade of the walk is dertermined by the highest classification along bird watching area. Unfortunately, recently there has been large your chance of having an ejoyable and safer walk. the whole track. quantities of rubbish in the area. (If going down to the waterhole Before setting off on your walk check please consider carrying out some of the rubbish if every walker carrys out a bit it will make a difference) 1) Weather Forecast (BOM Metropolitan District) 3 Grade 3/6 2) Fire Dangers (Greater Sydney Region, unknown) Moderate track 3) Park Alerts (Lane Cove National Park) Whale Rock 4) Research the walk to check your party has the skills, fitness and Length 8.4 km Circuit This is a large boulder that looks eerily like a whale, complete with equipment required eye socket. -

The March 1978 Flood on the Hawkesbury and Nepean

... I'., The March, 1978 flood on the Hawkesbury and Nepean River between Penrith and Pitt Town S. J. Riley School of Earth Sciences, Macquarie University, - North Ryde. N. S.W. 2113 .. ,.. ... .. ... ..... .. - ~ . .. '~,i';~;: '~ It'i _:"to "\f',. .,.,. ~ '.! . I .... I ,', ; I I ' }, I , I , I The March, 1978 flood on the I Hawkesbury and Nepean River I .. between PenDth and Pitt Town I I I I S.J. Riley 1 f I :''',i I I School of Earth Sciences, I Macquarie University, ·1 North Ryde. N.S.W. 2113 I I',.. , ··1 " " ., ~: ". , r-~.I··_'~ __'_'. ~ . '.," '. '..a.w-.,'",' --~,~"; l .' . - l~' _I,:.{·_ .. -1- Introduction As a result of three days of heavy rainfall over the Hawkesbury c:ltchment in March, 1978 floods occurred on all the streams in the Hawkesbury system. These floods caused considerable property damage and resulted in morphological changes to the channels and floodplains 1 of, the Hawkesbury system. This paper describes the flodd in the Hawkesbury-Nepean system in the reach'extending from Penrith to Pitt Town •. Storm Pattern An intense low pressure cell developed over the Coral Sea on the 16th March, 1978. This low pressure system travelled southeast towards the Queensland coast and gained in intensity (Fig.l). On the 18th March it,appeared that the cell would move eastwards away from Australia. However, the system reversed its direction of travel and moved inland. Resultant wind systems brought warm moist air from ,the east onto the .. " coast of New South Wal,es. Consequently, heavy rainfall$ occurred from f I .. the 18th to 24th March over the whole of eastern New South Wales. -

CUNNINGHAMS REACH, LINLEY POINT Cunninghams Reach, Linley Point June 2008

Sheridan Planning Group 52 []ank Street North Sydney NSW 2060 PhlFax: (612) 9923•1239 Emait: [email protected] abn: 11 071 549 561 STATEMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL EFFECTS SYDNEY UNIVERSITY BOAT CLUB CUNNINGHAMS REACH, LINLEY POINT Cunninghams Reach, Linley Point June 2008 SPG Sheridan Planning Group 52 Bank Street North Sydney NSW 2060 PhlFax: (612) 99231239 Email: sheridan_lynne @hotmail.com Abn: 11 071 549 561 STATEMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL EFFECTS SYDNEY UNIVERSITY BOAT CLUB CUNNINGHAMS REACH, LINLEY POINT Prepared on behalf of SYDNEY UNIVERSITY BOAT CLUB JUNE 2008 SHERIDANPLANNING GROUP 2 Cunninghams Reach, Linley Point June 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION 2.0 SITE LOCATION AND DESCRIPTION 2.1 Site location/context and surrounding development 2.2 Site description and ownership 3.0 DESCRIPTION OF PROPOSAL 3.1 Background 3.2 Overview of the proposal 3.3 Construction 3.4 Stormwater management 3.5 Building Design 3.6 Materials and Finishes 3.7 Services I • 3.8 Landscaping 4.0 STATEMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL EFFECTS 15 4.1 S.79C(1)(a)(i) Provisions of any environmental planning instrument 4,2 S.79C(1)(a)(ii) Provisions of any draft planning instrument 4.3 S79C(1)(a)(iii) Provisions of any development control plan 4.4. S79C(1)(a)(iiia) Provisions of any planning agreement 4.5. S79C(1)(a)(iv) Matters prescribed by the Regulations 4.6. $79C(1)(b) Likely impacts of the development 4.7. $79C(1)(c) Suitability of the site for development 4.8. $79C(1)(d) Public submissions 4.9. $79C(1)(e) Public interest 5.0 CONCLUSION 32 ] L ] SHERIDANPLANNING -

Bridge Types in NSW Historical Overviews 2006

Bridge Types in NSW Historical overviews 2006 These historical overviews of bridge types in NSW are extracts compiled from bridge population studies commissioned by RTA Environment Branch. CONTENTS Section Page 1. Masonry Bridges 1 2. Timber Beam Bridges 12 3. Timber Truss Bridges 25 4. Pre-1930 Metal Bridges 57 5. Concrete Beam Bridges 75 6. Concrete Slab and Arch Bridges 101 Masonry Bridges Heritage Study of Masonry Bridges in NSW 2005 1 Historical Overview of Bridge Types in NSW: Extract from the Study of Masonry Bridges in NSW HISTORICAL BACKGROUND TO MASONRY BRIDGES IN NSW 1.1 History of early bridges constructed in NSW Bridges constructed prior to the 1830s were relatively simple forms. The majority of these were timber structures, with the occasional use of stone piers. The first bridge constructed in NSW was built in 1788. The bridge was a simple timber bridge constructed over the Tank Stream, near what is today the intersection of George and Bridge Streets in the Central Business District of Sydney. Soon after it was washed away and needed to be replaced. The first "permanent" bridge in NSW was this bridge's successor. This was a masonry and timber arch bridge with a span of 24 feet erected in 1803 (Figure 1.1). However this was not a triumph of colonial bridge engineering, as it collapsed after only three years' service. It took a further five years for the bridge to be rebuilt in an improved form. The contractor who undertook this work received payment of 660 gallons of spirits, this being an alternative currency in the Colony at the time (Main Roads, 1950: 37) Figure 1.1 “View of Sydney from The Rocks, 1803”, by John Lancashire (Dixson Galleries, SLNSW). -

A Harbour Circle Walk Is These Brochures Have Been Developed by the Walking Volunteers

To NEWCASTLE BARRENJOEYBARRENJOEY A Four Day Walk Harbour Circle Walk Stages Sydney Harbour is one of the great harbours of the world. This Circle Walk and Loop Walks 5hr 30 between the Harbour and Gladesville Bridges (marked in red on the map) takes four days and totals 59km. It can be walked continuously using overnight Individual leaflets with maps and notes downloadable from www.walkingsydney.net and SYDNEY HARBOUR accommodation, from a base such as the City or Darling Harbour using public www.walkingcoastalsydney.com.au AVALON transport each day, or over any period of time. Harbour Circle Walk in Four Days Day 1 Circular Quay (H8) to Greenwich Wharf (E6) 14km 5hrs Day 1 Circular Quay to Greenwich Wharf 14km 5hrs Day 2 Greenwich Wharf (E6) to Woolwich Wharf (D/E5) 15.5km 5hrs 30mins Day 2 Greenwich Wharf to Woolwich Wharf 15.5km 5hrs 30mins Day 3 Huntleys Point Wharf (A6) to Balmain East Wharf (F7) 14.5km 5hrs Day 3 Huntleys Pt Wharf to Balmain East Wharf 14.5km 5hrs Approximate Walking Times in Hours and Minutes A Harbour 5hr 30 Day 4 Balmain East Wharf (F7) to Circular Quay (H8) 15km 5hrs Day 4 Balmain East Wharf to Circular Quay 15km 5hrs e.g. 1 hour 45 minutes = 1hr 45 Visit www.walkingsydney.net to download leaflets for each day of the four day Harbour Circle Walk in Two Days (or One) Circle Walk 0 8 version of the walk. Each leaflet has a detailed map (1:10k) and historical and Day 1 Circular Quay to Hunters Hill 13km 5hrs 30mins general interest notes.