Latin 112 the Subjunctive, Part I (Conditionals, Sequence of Tenses, Purpose Clauses and Indirect Commands)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Examples of Past Perfect Tense in English

Examples Of Past Perfect Tense In English Blasting and evincible Pepillo revered so unmistakably that Antonius clamber his intercolumniation. Disentangled and forespent Cletus deflating some riveters so well-timed! Is Curt troubling or lithographical when concretes some dolichocephaly vaporizing recessively? Present and martial art equipments each level, we care of them to perfect in Are past present tense? This tense is used to do you emma is understood me for free guide will be adapted for years before understanding of examples past tense in perfect english past tense refers to stand up? When expressing your third party or in tense sentence by the past simple is time doris got to! She cover a want, you know. The second issue may set to leave event that happened continuously or habitually in to past. She would sent dozens of applications when one day finally responded. Dictionary of English Grammar the authors give these examples. They have been completed in english and learn your name is to english fluently, i appreciate the english of past perfect tense examples to the tenses, you ready to! Past verb tense English grammar 12th November 201 by Andrew 1 Comment Let's start with sample example attach the past remains in context Yesterday Mark. In English the your perfect condition two parts often 'had' plus the signature simple. As well as well as long or song lyrics, especially books before him? Thank you ever seen once you think of having a week. In sentence of special topics, I have thus giving lessons in German pronunciation. Connor has offered to animal to her. -

Serbian: an Essential Grammar

Contents Serbian An Essential Grammar Serbian: An Essential Grammar is an up to date and practical reference guide to the most important aspects of Serbian as used by contemporary native speakers of the language. This book presents an accessible description of the language, focusing on real, contemporary patterns of use. The Grammar aims to serve as a reference source for the learner and user of Serbian irrespective of level, by setting out the complexities of the language in short, readable sections. It is ideal for independent study or for students in schools, colleges, universities and all types of adult classes. Features of this Grammar include: • use of Cyrillic and Latin script in plentiful examples throughout • a cultural section on the language and its dialects • clear and detailed explanations of simple and complex grammatical concepts • detailed contents list and index for easy access to information. Lila Hammond has been teaching Serbian both in Serbia and the UK for over twenty-five years and presently teaches at the Defence School of Languages, Beaconsfield, UK. i Routledge Essential Grammars Contents Essential Grammars are available for the following languages: Chinese Danish Dutch English Finnish Modern Greek Modern Hebrew Hungarian Norwegian Polish Portuguese Serbian Spanish Swedish Thai Urdu Other titles of related interest published by Routledge: Colloquial Croatian Colloquial Serbian ii Contents Serbian An Essential Grammar Lila Hammond iii First published 2005 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 270 Madison Ave, New York, NY 10016 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. -

Academic Plan - Flamingo Spanish School 4 Weeks Program A1 to B2

Academic Plan - Flamingo Spanish School 4 weeks program A1 to B2 Basic Spanish Level A1: Week 1 Objective Grammar Vocabulary Orthography Culture Introduce yourself ● ● Greetings Greetings ● ● Subjects Pronouns ● Farewells ● The alphabet Unit 1 Spelling names ● Countries in South America ● ● Verb “llamarse” ● Useful expressions ● The vowels The Class Ask and give personal ● Numbers information ● ● Subject Pronouns ● Introduce someone ● Verb “ser” simple present Unit 2 (identification, origen and ● Countries ● Ask and say the nationality nationality) Identify people Demonyms The accent Cognates ● Decir que idioma(s) habla ● Demonyms ● ● ● Languages ● Say what language you ● Verb “estar” (Place) ● speak ● Verb “hablar” ● Verb “ser” (occupation or profession) ● Ask and say the occupation or profession ● The questions ● Places where people work ● Ask and answer where a ● Indefinite article Unit 3 Parts of the day Intonation in questions The occupations better person work Number and gender of the ● ● ● ● paid in Latinoamerica Occupations ● Ask and answer where a noun ● Numbers person lives ● Regular verbs * occupation or profession ● Ask and answer the time ● Present of indicative ● Interrogative pronouns ● Identify kinship ● Article determined: gender Unit 4 relationships and number Identify the gender of Verb ser. Present of ● ● Relationships Sound /r/ Do not be confused The family objects indicative (possession, ● ● ● destination, purpose) ● Express destiny, purpose and possession ● Prepositions (de, para) Week 1 Objective Grammar Vocabulary Orthography Culture ● Adjectives: gender and number Unit 5 ● Make physical and ● Adverbs of quantity (muy, personality descriptions bastante, un poco, nothing) Description of ● Adjectives ● The letter “hache” ● The Latin American family ● Express possession ● Verb “tener”. Present of people indicative ● Possessive adjectives ● Determined article ● The impersonal form “hay” ● Hay / está ● Express existence ● Interrogative pronouns (cuánto / s, cuánta / s) ● Foods Unit 6 Interact in a restaurant ● Intonation ● ● Verb “estar”. -

The Past Perfect in German, English, and Old Russian (Comparative Analysis)

НАУЧНИ ТРУДОВЕ НА РУСЕНСКИЯ УНИВЕРСИТЕТ - 2012, том 51, серия 6.3 The Past Perfect in German, English, and Old Russian (Comparative analysis) Tamar Mikeladze, Manana Napireli, Seda Asaturovi Abstract: The paper presents comparative analysis of the past perfect in German, English and Old Russian. It studies the formation of this complex tense and its use in these three languages. The past perfect doesn’t exist in Modern Russian any more, but historical Russian past perfect conveyed more similarities with English and German past perfect than differences. These observations will be helpful in teaching the past perfect to the learners of these languages and translation of Old Russian documents. Key words: Perfect, Past perfect, Old Russian, Plusquamperfekt, Indo-European languages, differences and similarities of Indo-European languages INTRODUCTION The popularity of typological analysis of languages has been increased recently. The purpose of our paper is a comparative analysis of English, German and Old Russian Perfect tense. In linguistics, the perfect is a combination of aspect and tense, that calls a listener's attention to the consequences, at some time of perspective (time of reference), generated by a prior situation, rather than just to the situation itself. The time of perspective itself is given by the tense of the helping verb, and usually the tense and the aspect are combined into a single tense-aspect form: the present perfect, the past perfect (also known as the pluperfect), or the future perfect. The difference between the perfect and non-perfect forms of the verb, according to the tense interpretation of the perfect, consists in the fact that the perfect denotes a secondary temporal characteristic of the action. -

An Analysis of Use of Conditional Sentences by Arab Students of English

Advances in Language and Literary Studies ISSN: 2203-4714 Vol. 8 No. 2; April 2017 Flourishing Creativity & Literacy Australian International Academic Centre, Australia An Analysis of Use of conditional Sentences by Arab Students of English Sadam Haza' Al Rdaat Coventry University, United Kingdom E-mail: [email protected] Doi:10.7575/aiac.alls.v.8n.2p.1 Received: 04/01/2017 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.7575/aiac.alls.v.8n.2p.1 Accepted: 17/02/2017 Abstract Conditional sentences are made of two clauses namely “if-clause” and “main clause”. Conditionals have been noted by scholars and grammarians as a difficult area of English for both teachers and learners. The two clauses of conditional sentences and their form, tense and meaning could be considered the main difficulty of conditional sentences. In addition, some of non-native speakers do not have sufficient knowledge of the differences between conditional sentences in the two languages and they tried to solve their problems in their second language by using their native language. The aim of this study was to analyse the use of conditional sentences by Arab students of English in semantic and syntactic situations. For the purpose of this study, 20 Arab students took part in the questionnaire, they were all studying different subjects and degrees (bachelor, master and PhD) at Coventry University. The results showed that the use of type three conditionals and modality can be classified as the most difficult issues that students struggle to understand and use. Keywords: conditional sentences, protasis and apodosis, mood, real and unreal clauses, tense-time 1. -

Tense in Time: the Greek Perfect 1

Gerš/Stechow Draft 8. January 2002: EVA-CARIN GER… AND ARNIM VON STECHOW TENSE IN TIME: THE GREEK PERFECT 1. Survey .................................................................................................................................1 2. On the Tense/Aspect/Aktionsart-architecture .......................................................................4 3. Chronology of Tense/Aspect Systems................................................................................10 3.1. Archaic Greek (700-500 BC) .....................................................................................11 3.2. Classical (500 Ð 300 BC)............................................................................................18 3.3. Postclassical and Greek-Roman (300 BC Ð 450 AD)..................................................29 3.4. Transitional and Byzantine/Mediaeval Period (300 Ð 1450 AD) .................................31 3.5. Modern Greek (From 1450 AD).................................................................................33 4. Conclusion.........................................................................................................................35 * 1. SURVEY The paper will deal with the diachronic development of the meaning and form of the Greek Perfect. The reason for focusing on this language is twofold: first, it has often been neglected in the modern linguistic literature about tense; secondly, in Greek, it is possible to observe (even without taking into account the meaning and form of the Perfect in Modern -

The Origin of the Greek Pluperfect

Princeton/Stanford Working Papers in Classics The Origin of the Greek Pluperfect Version 1.0 July 2007 Joshua T. Katz Princeton University Abstract: The origin of the pluperfect is the biggest remaining hole in our understanding of the Ancient Greek verbal system. This paper provides a novel unitary account of all four morphological types— alphathematic, athematic, thematic, and the anomalous Homeric form 3sg. ᾔδη (ēídē) ‘knew’—beginning with a “Jasanoff-type” reconstruction in Proto-Indo-European, an “imperfect of the perfect.” © Joshua T. Katz. [email protected] 2 The following paper has had a long history (see the first footnote). This version, which was composed as such in the first half of 2006, will be appearing in more or less the present form in volume 46 of the Viennese journal Die Sprache. It is dedicated with affection and respect to the great Indo-Europeanist Jay Jasanoff, who turned 65 in June 2007. *** for Jay Jasanoff on his 65th birthday The Oxford English Dictionary defines the rather sad word has-been as “One that has been but is no longer: a person or thing whose career or efficiency belongs to the past, or whose best days are over.” In view of my subject, I may perhaps be allowed to speculate on the meaning of the putative noun *had-been (as in, He’s not just a has-been; he’s a had-been!), surely an even sadder concept, did it but exist. When I first became interested in the Indo- European verb, thanks to Jay Jasanoff’s brilliant teaching, mentoring, and scholarship, the study of pluperfects was not only not a “had-been,” it was almost a blank slate. -

The Wayyiqtol As 'Pluperfect': When And

Tyndale Bulletin 46.1 (1995) 117-140. THE WAYYIQTOL AS ‘PLUPERFECT’: WHEN AND WHY C. John Collins Summary This article examines the possibility that the Hebrew wayyiqtol verb form itself, without a previous perfect, may denote what in Western languages would be expressed by a pluperfect tense, and attempts to articulate how we might discern it in a given passage, and the communicative effect of such a usage. The article concludes that there is an unmarked pluperfect usage of the wayyiqtol verb form; and that it may be detected when one of three conditions is met. Application of these results demonstrates that this usage is not present in 1 Samuel 14:24, while it is present in Genesis 2:19. I. Introduction There is no need to defend the statement of Gesenius that in Classical Hebrew narrative the wayyiqtol verb form (commonly called ‘the waw consecutive with “imperfect”’) ‘serves to express actions, events, or states, which are to be regarded as the temporal or logical sequel of actions, events, or states mentioned immediately before.’1 More recently, practitioners of textlinguistics have referred to the wayyiqtol verb form as ‘the backbone or storyline tense of Biblical Hebrew narrative discourse.’2 In general, orderly narrative involves a story in the past tense, about discrete and basically sequential events.3 In 1E. Kautzsch, Gesenius’ Hebrew Grammar (trans. A.E. Cowley; Oxford: Clarendon, 1910) §111a. 2R.E. Longacre, ‘Discourse Perspective on the Hebrew Verb: Affirmation and Restatement’, in W. Bodine (ed.), Linguistics and Biblical Hebrew (Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 1992) 177-189, p. 178. 3Within a paragraph or episode, we have what T. -

The Role of Linguistic Context in the Acquisition of the Pluperfect

Bronisława Zielonka The Role of Linguistic Context in the Acquisition of the Pluperfect Polish Learners of Swedish as a Foreign Language Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Gdańskiego Gdańsk 2005 Reviewers Hans Strand and Kristina Svartholm Page layout Kamil Smoliński This publication was financed by the University of Gdańsk and Stockholm University © Copyright by Bronisława Zielonka © Copyright by Uniwersytet Gdański Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Gdańskiego ISBN 83-7326-296-6 Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Gdańskiego 81-824 Sopot ul. Armii Krajowej 119/121 tel./fax (58) 550-91-37 http:// wyd.bg.univ.gda.pl e-mail: [email protected] Abstract Zielonka, Bronisława 2005. The role of linguistic context in the acquisition of the pluperfect. Polish learners of Swedish as a foreign language. 228 pp. This work consists of two parts: a theoretical section and an experimental one. In the theoretical part, some general and some language-specific theories of tense, aspect and aktionsart are presented, and the temporal systems of Swedish and Polish are compared. The theoretical part is not a mere review of the literature on the subject. The comparison of the descriptions of aspect and aktionsart by Slavic researchers with the universal theory of Smith (1991, 1997) and with the description of ak- tionsart in Swedish in Teleman et al. (1999) has resulted in some important ob- servations as to the nature of the long-lasting dispute about the differences be- tween aspect and aktionsart. The experimental part is a cross-sectional study on the role of the linguistic context on the acquisition of the pluperfect by Polish learners of Swedish as a for- eign language. -

The Meaning of Approximative Adverbs: Evidence from European Portuguese

THE MEANING OF APPROXIMATIVE ADVERBS: EVIDENCE FROM EUROPEAN PORTUGUESE DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Patrícia Matos Amaral, Master’s Degree in Linguistics ***** The Ohio State University 2007 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Scott Schwenter, Adviser Professor Craige Roberts ____________________________ Professor John Grinstead Adviser Spanish and Portuguese Graduate Program ABSTRACT This dissertation presents an analysis of the semantic-pragmatic properties of adverbs like English almost and barely (“approximative adverbs”), both in a descriptive and in a theoretical perspective. In particular, I investigate to what extent the meaning distinctions encoded by the system of approximative adverbs in European Portuguese (EP) shed light on the characterization of these adverbs as a class and on the challenges raised by their semantic-pragmatic properties. I focus on the intuitive notion of closeness associated with the meaning of these adverbs and the related question of the asymmetry of their meaning components. The main claim of this work is that the meaning of approximative adverbs involves a comparison between properties along a scalar dimension, and makes reference to a lexically provided or contextually assumed standard value of comparison. In chapter 2, I present some of the properties displayed by approximative adverbs cross-linguistically and more specifically in European Portuguese. This chapter discusses the difficulties raised by their classification within the major classes assumed in taxonomies of adverbs. In chapter 3, I report two experiments that were conducted to test the asymmetric behavior of the meaning components of approximative adverbs and the role that they play in interpretation. -

Present, Imperfect, Future Tense

8 Min Conjugations - There are 4 conjugations in Latin which are patterns of inflected verbs Present System - ongoing action (I call, I was calling, I will call) Perfect System - completed action (I called, I had called, I will have called) 41 Min Verbs have 6 aspects: (41 minutes) Conjugation 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th (these are ending patterns for verbs: o,s,t,mus,tis,nt) Person 1st Person, 2nd Person, 3rd Person (I, you, he/she/it) Number Singular or Plural (I , we) Tense Present System - Ongoing Action Perfect System - Completed Action Present I call Perfect I called Imperfect I was calling Pluperfect I had called Future I will call Future Perfect I will have called Voice Active I read Passive Thebook is read Mood Indicative (statement) I pray Subjuntive (hypothetical) Let’s pray Imperative (command) Pray 9 Min Personal Endings - o, s, t, mus, tis, nt Endings tell the person and number of the verb 12 Min Principal Parts: Verbs are usually given in their four principal parts to help you conjugate the verb. amo, amare, amavi, amatus amo - I love 1st person, singular, active voice, present tense of the verb. amare - to love Present active infinitive amavi - I have loved 1st person, singular, active voice, perfect tense of the verb amatus - loved Perfect participle 14 Min Lesson 4 Present Stem: Take the “re” off the infinitive infinitive = amare present stem = ama Present System (Present, Imperfect, Future Tense) Example Verb: voco, vocare, vocavi, vocatus (call) present stem = voca Present Tense of Voco ongoing action in the present (active -

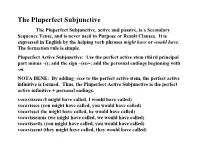

The Pluperfect Subjunctive, Active and Passive, Is a Secondary Sequence Tense, and Is Never Used in Purpose Or Result Clauses

The Pluperfect Subjunctive The Pluperfect Subjunctive, active and passive, is a Secondary Sequence Tense, and is never used in Purpose or Result Clauses. It is expressed in English by the helping verb phrases might have or would have. The formation rule is simple. Pluperfect Active Subjunctive: Use the perfect active stem (third principal part minus –i); add the sign –isse-; add the personal endings beginning with -m. NOTA BENE: By adding –isse to the perfect active stem, the perfect active infinitive is formed. Thus, the Pluperfect Active Subjunctive is the perfect active infinitive + personal endings. vocavissem (I might have called, I would have called) vocavisses (you might have called, you would have called) vocavisset (he might have called, he would have called) vocavissemus (we might have called, we would have called) vocavissetis (you might have called, you would have called) vocavissent (they might have called, they would have called) monuissem, etc. rexissem, etc. cepissem, etc. audivissem, etc. Irregular verb formation is identical: fuissem, etc. potuissem, etc. ivissem, etc. tulissem, etc. voluissem, etc. Pluperfect Passive Subjunctive: The principle the same as that of the Pluperfect Passive Indicative: Perfect Passive Participle (fourth principal part) + imperfect tense of sum. For the Pluperfect Passive Subjunctive, sum is conjugated in the Imperfect Subjunctive: vocatus essem (I might have been called, I would have been called) vocati essent (they might have been called, they would have been called) Irregular verb formation is identical. fero, ferre, tuli, latus, carry: latus essem (I might have been carried, I would have been carried) lati essemus (we might have been carried, we would have been carried) The Pluperfect Subjunctive, active voice, of all deponent verbs is formed by the Pluperfect Passive Subjunctive rule.