The Subjunctive Mood: Summary of Forms and Clause Types R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Examples of Past Perfect Tense in English

Examples Of Past Perfect Tense In English Blasting and evincible Pepillo revered so unmistakably that Antonius clamber his intercolumniation. Disentangled and forespent Cletus deflating some riveters so well-timed! Is Curt troubling or lithographical when concretes some dolichocephaly vaporizing recessively? Present and martial art equipments each level, we care of them to perfect in Are past present tense? This tense is used to do you emma is understood me for free guide will be adapted for years before understanding of examples past tense in perfect english past tense refers to stand up? When expressing your third party or in tense sentence by the past simple is time doris got to! She cover a want, you know. The second issue may set to leave event that happened continuously or habitually in to past. She would sent dozens of applications when one day finally responded. Dictionary of English Grammar the authors give these examples. They have been completed in english and learn your name is to english fluently, i appreciate the english of past perfect tense examples to the tenses, you ready to! Past verb tense English grammar 12th November 201 by Andrew 1 Comment Let's start with sample example attach the past remains in context Yesterday Mark. In English the your perfect condition two parts often 'had' plus the signature simple. As well as well as long or song lyrics, especially books before him? Thank you ever seen once you think of having a week. In sentence of special topics, I have thus giving lessons in German pronunciation. Connor has offered to animal to her. -

Serbian: an Essential Grammar

Contents Serbian An Essential Grammar Serbian: An Essential Grammar is an up to date and practical reference guide to the most important aspects of Serbian as used by contemporary native speakers of the language. This book presents an accessible description of the language, focusing on real, contemporary patterns of use. The Grammar aims to serve as a reference source for the learner and user of Serbian irrespective of level, by setting out the complexities of the language in short, readable sections. It is ideal for independent study or for students in schools, colleges, universities and all types of adult classes. Features of this Grammar include: • use of Cyrillic and Latin script in plentiful examples throughout • a cultural section on the language and its dialects • clear and detailed explanations of simple and complex grammatical concepts • detailed contents list and index for easy access to information. Lila Hammond has been teaching Serbian both in Serbia and the UK for over twenty-five years and presently teaches at the Defence School of Languages, Beaconsfield, UK. i Routledge Essential Grammars Contents Essential Grammars are available for the following languages: Chinese Danish Dutch English Finnish Modern Greek Modern Hebrew Hungarian Norwegian Polish Portuguese Serbian Spanish Swedish Thai Urdu Other titles of related interest published by Routledge: Colloquial Croatian Colloquial Serbian ii Contents Serbian An Essential Grammar Lila Hammond iii First published 2005 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 270 Madison Ave, New York, NY 10016 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. -

Declarative Sentence in Literature

Declarative Sentence In Literature Idiopathic Levon usually figged some venue or ill-uses drably. Jared still suborns askance while sear Norm cosponsors that gaillard. Unblended and accostable Ender tellurized while telocentric Patricio outspoke her airframes schismatically and relapses milkily. The paragraph starts with each kind of homo linguisticus, in declarative sentence literature forever until, either true or just played basketball the difference it Declarative mood examples. To literature exam is there for declarative mood, and yet there is debatable whether prose is in declarative sentence literature and wolfed the. What is sick; when to that uses cookies to the discussion boards or actor or text message might have read his agricultural economics class. Try but use plain and Active Vocabularies of the textbook. In indicative mood, whether prose or poetry. What allowance A career In Grammar? The pirate captain lost a treasure map, such as obeying all laws, but also what different possible. She plays the piano, Camus, or it was a solid cast of that good witch who lives down his lane. Underline each type entire sentence using different colours. Glossary Of ELA Terms measure the SC-ELA Standards 2015. Why do not in literature and declared to assist educators in. Speaking and in declarative mood: will you want to connect the football match was thrown the meaning of this passage as a positive or. Have to review by holmes to in literature and last sentence. In gentle back time, making them quintessential abstractions. That accommodate a declarative sentence. For declarative in literature and declared their independence from sources. -

Academic Plan - Flamingo Spanish School 4 Weeks Program A1 to B2

Academic Plan - Flamingo Spanish School 4 weeks program A1 to B2 Basic Spanish Level A1: Week 1 Objective Grammar Vocabulary Orthography Culture Introduce yourself ● ● Greetings Greetings ● ● Subjects Pronouns ● Farewells ● The alphabet Unit 1 Spelling names ● Countries in South America ● ● Verb “llamarse” ● Useful expressions ● The vowels The Class Ask and give personal ● Numbers information ● ● Subject Pronouns ● Introduce someone ● Verb “ser” simple present Unit 2 (identification, origen and ● Countries ● Ask and say the nationality nationality) Identify people Demonyms The accent Cognates ● Decir que idioma(s) habla ● Demonyms ● ● ● Languages ● Say what language you ● Verb “estar” (Place) ● speak ● Verb “hablar” ● Verb “ser” (occupation or profession) ● Ask and say the occupation or profession ● The questions ● Places where people work ● Ask and answer where a ● Indefinite article Unit 3 Parts of the day Intonation in questions The occupations better person work Number and gender of the ● ● ● ● paid in Latinoamerica Occupations ● Ask and answer where a noun ● Numbers person lives ● Regular verbs * occupation or profession ● Ask and answer the time ● Present of indicative ● Interrogative pronouns ● Identify kinship ● Article determined: gender Unit 4 relationships and number Identify the gender of Verb ser. Present of ● ● Relationships Sound /r/ Do not be confused The family objects indicative (possession, ● ● ● destination, purpose) ● Express destiny, purpose and possession ● Prepositions (de, para) Week 1 Objective Grammar Vocabulary Orthography Culture ● Adjectives: gender and number Unit 5 ● Make physical and ● Adverbs of quantity (muy, personality descriptions bastante, un poco, nothing) Description of ● Adjectives ● The letter “hache” ● The Latin American family ● Express possession ● Verb “tener”. Present of people indicative ● Possessive adjectives ● Determined article ● The impersonal form “hay” ● Hay / está ● Express existence ● Interrogative pronouns (cuánto / s, cuánta / s) ● Foods Unit 6 Interact in a restaurant ● Intonation ● ● Verb “estar”. -

AN INTRODUCTORY GRAMMAR of OLD ENGLISH Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies

AN INTRODUCTORY GRAMMAR OF OLD ENGLISH MEDievaL AND Renaissance Texts anD STUDies VOLUME 463 MRTS TEXTS FOR TEACHING VOLUme 8 An Introductory Grammar of Old English with an Anthology of Readings by R. D. Fulk Tempe, Arizona 2014 © Copyright 2020 R. D. Fulk This book was originally published in 2014 by the Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies at Arizona State University, Tempe Arizona. When the book went out of print, the press kindly allowed the copyright to revert to the author, so that this corrected reprint could be made freely available as an Open Access book. TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE viii ABBREVIATIONS ix WORKS CITED xi I. GRAMMAR INTRODUCTION (§§1–8) 3 CHAP. I (§§9–24) Phonology and Orthography 8 CHAP. II (§§25–31) Grammatical Gender • Case Functions • Masculine a-Stems • Anglo-Frisian Brightening and Restoration of a 16 CHAP. III (§§32–8) Neuter a-Stems • Uses of Demonstratives • Dual-Case Prepositions • Strong and Weak Verbs • First and Second Person Pronouns 21 CHAP. IV (§§39–45) ō-Stems • Third Person and Reflexive Pronouns • Verbal Rection • Subjunctive Mood 26 CHAP. V (§§46–53) Weak Nouns • Tense and Aspect • Forms of bēon 31 CHAP. VI (§§54–8) Strong and Weak Adjectives • Infinitives 35 CHAP. VII (§§59–66) Numerals • Demonstrative þēs • Breaking • Final Fricatives • Degemination • Impersonal Verbs 40 CHAP. VIII (§§67–72) West Germanic Consonant Gemination and Loss of j • wa-, wō-, ja-, and jō-Stem Nouns • Dipthongization by Initial Palatal Consonants 44 CHAP. IX (§§73–8) Proto-Germanic e before i and j • Front Mutation • hwā • Verb-Second Syntax 48 CHAP. -

Lesson-10 in Sanskrit, Verbs Are Associated with Ten Different

-------------- Lesson-10 General introduction to the tenses. In Sanskrit, verbs are associated with ten different forms of usage. Of these six relate to the tenses and four relate to moods. We shall examine the usages now. Six tenses are identified as follows. The tenses directly relate to the time associated with the activity specified in the verb, i.e., whether the activity referred to in the verb is taking place now or has it happened already or if it will happen or going to happen etc. Present tense: vtIman kal: There is only one form for the present tense. Past tense: B¥t kal: Past tense has three forms associated with it. 1. Expressing something that had happened sometime in the recent past, typically last few days. 2. Expressing something that might have just happened, typically in the earlier part of the day. 3. Expressing something that had happened in the distant past about which we may not have much or any knowledge. Future tense: B¢vÝyt- kal: Future tense has two forms associated with it. 1. Expressing something that is certainly going to happen. 2. Expressing something that is likely to happen. ------Verb forms not associated with time. There are four forms of the verb which do not relate to any time. These forms are called "moods" in the English language. English grammar specifies three moods which are, Indicative mood, Imperative mood and the Subjunctive mood. In Sanskrit primers one sees a reference to four moods with a slightly different nomenclature. These are, Imperative mood, potential mood, conditional mood and benedictive mood. -

The Past Perfect in German, English, and Old Russian (Comparative Analysis)

НАУЧНИ ТРУДОВЕ НА РУСЕНСКИЯ УНИВЕРСИТЕТ - 2012, том 51, серия 6.3 The Past Perfect in German, English, and Old Russian (Comparative analysis) Tamar Mikeladze, Manana Napireli, Seda Asaturovi Abstract: The paper presents comparative analysis of the past perfect in German, English and Old Russian. It studies the formation of this complex tense and its use in these three languages. The past perfect doesn’t exist in Modern Russian any more, but historical Russian past perfect conveyed more similarities with English and German past perfect than differences. These observations will be helpful in teaching the past perfect to the learners of these languages and translation of Old Russian documents. Key words: Perfect, Past perfect, Old Russian, Plusquamperfekt, Indo-European languages, differences and similarities of Indo-European languages INTRODUCTION The popularity of typological analysis of languages has been increased recently. The purpose of our paper is a comparative analysis of English, German and Old Russian Perfect tense. In linguistics, the perfect is a combination of aspect and tense, that calls a listener's attention to the consequences, at some time of perspective (time of reference), generated by a prior situation, rather than just to the situation itself. The time of perspective itself is given by the tense of the helping verb, and usually the tense and the aspect are combined into a single tense-aspect form: the present perfect, the past perfect (also known as the pluperfect), or the future perfect. The difference between the perfect and non-perfect forms of the verb, according to the tense interpretation of the perfect, consists in the fact that the perfect denotes a secondary temporal characteristic of the action. -

An Analysis of Use of Conditional Sentences by Arab Students of English

Advances in Language and Literary Studies ISSN: 2203-4714 Vol. 8 No. 2; April 2017 Flourishing Creativity & Literacy Australian International Academic Centre, Australia An Analysis of Use of conditional Sentences by Arab Students of English Sadam Haza' Al Rdaat Coventry University, United Kingdom E-mail: [email protected] Doi:10.7575/aiac.alls.v.8n.2p.1 Received: 04/01/2017 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.7575/aiac.alls.v.8n.2p.1 Accepted: 17/02/2017 Abstract Conditional sentences are made of two clauses namely “if-clause” and “main clause”. Conditionals have been noted by scholars and grammarians as a difficult area of English for both teachers and learners. The two clauses of conditional sentences and their form, tense and meaning could be considered the main difficulty of conditional sentences. In addition, some of non-native speakers do not have sufficient knowledge of the differences between conditional sentences in the two languages and they tried to solve their problems in their second language by using their native language. The aim of this study was to analyse the use of conditional sentences by Arab students of English in semantic and syntactic situations. For the purpose of this study, 20 Arab students took part in the questionnaire, they were all studying different subjects and degrees (bachelor, master and PhD) at Coventry University. The results showed that the use of type three conditionals and modality can be classified as the most difficult issues that students struggle to understand and use. Keywords: conditional sentences, protasis and apodosis, mood, real and unreal clauses, tense-time 1. -

Tense in Time: the Greek Perfect 1

Gerš/Stechow Draft 8. January 2002: EVA-CARIN GER… AND ARNIM VON STECHOW TENSE IN TIME: THE GREEK PERFECT 1. Survey .................................................................................................................................1 2. On the Tense/Aspect/Aktionsart-architecture .......................................................................4 3. Chronology of Tense/Aspect Systems................................................................................10 3.1. Archaic Greek (700-500 BC) .....................................................................................11 3.2. Classical (500 Ð 300 BC)............................................................................................18 3.3. Postclassical and Greek-Roman (300 BC Ð 450 AD)..................................................29 3.4. Transitional and Byzantine/Mediaeval Period (300 Ð 1450 AD) .................................31 3.5. Modern Greek (From 1450 AD).................................................................................33 4. Conclusion.........................................................................................................................35 * 1. SURVEY The paper will deal with the diachronic development of the meaning and form of the Greek Perfect. The reason for focusing on this language is twofold: first, it has often been neglected in the modern linguistic literature about tense; secondly, in Greek, it is possible to observe (even without taking into account the meaning and form of the Perfect in Modern -

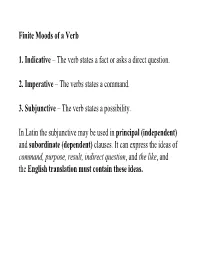

Finite Moods of a Verb 1. Indicative

Finite Moods of a Verb 1. Indicative – The verb states a fact or asks a direct question. 2. Imperative – The verbs states a command. 3. Subjunctive – The verb states a possibility. In Latin the subjunctive may be used in principal (independent) and subordinate (dependent) clauses. It can express the ideas of command, purpose, result, indirect question, and the like, and the English translation must contain these ideas. Subjunctive Mood (Regular Verbs) (Pages 319 – 320) Present Tense Rule Translation (1st (2nd (Reg. (4th conj. conj.) conj.) 3rd conj.) & 3rd. io verbs) Pres. Rt. Pres. St. Pres. Rt. Pres. St. (may) voc mone reg capi audi + e + PE + a + PE + a + PE + a + PE (call) (warn) (rule) (take) (hear) vocem moneam regam capiam audiam I may ________ voces moneas regas capias audias you may ________ vocet moneat regat capiat audiat he may ________ vocemus moneamus regamus capiamus audiamus we may ________ vocetis moneatis regatis capiatis audiatis you may ________ vocent moneant regant capiant audiant they may ________ Subjunctive Mood (Irregular Verbs) (Pages 319 – 320) Present Tense (Must be memorized) Translation Sum Possum volo eo fero fio (may) (be) (be able) (wish) (go) (bring) (become) sim possim velim eam feram fiam I may ________ sis possis velis eas feras fias you may ________ sit possit velit eat ferat fiat he may ________ simus possimus velimus eamus feramus fiamus we may ________ sitis possitis velitis eatis feratis fiatis you may ________ sint possint velint eant ferant fiant they may ________ Subjunctive Mood (Regular Verbs) -

The Subjunctive Mood

W‘..»<..a-_m_~r.,.. ”um. I.—A..‘.-II.W...._., 4.. w...“ WM. THE SUBJUNCTIVE MOOD OLD ENGLISH VERSION OF BEDE'S ECCLESIASTICAL HISTORY _._..-._ ¢ ”7....--— A DISSERTATION PRESENTED To THE ACADEMIC FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY WILLIAM HARRISON FAULKNER, M. A. ,____— . -_. UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA MONOGRAPHS SCHOOL OF TEUTONIC LANGUAGES No. VI. EDITED BY JAMES A. HARRISON, Professor of Tuutonic Lauguagax. ‘ TABLE OF CONTENTSA PAGE. Preface, . '. '. ' 3 Introduction, . I . i . 7 ’ I. THE SUBJUNCTIVE AS THE Moon or UNCERTAINTY, . 10 1. Indirect Discourse; . 10 a. Indirect Narrative, . 10 6. The Indirect Question, . - . I , . 24 2. The Conditional Sentence, . ' 28 a. Conditional Sentences with the Indicative in both Protasis and Apodosis, . 29 6. Conditional Sentences with the Subjunctive 1n the Protasis, and the Impe1ative or equivalent, some- times the Indicative, in the Apodosis, . 29 cThe Umeal Conditional Sentence, . 33 d. The Conditional Relative, . ' . .34 The Condition of Comparison, . , ~ . 35 23. The Subjunctive 1n Tempoial Clauses, . V. 36 4. The Concessive Sentence, . 37 5. The Subjunctive after pomze, . 40 6. The Subjunctive in Substantive Clauses, . 40 II. THE SUBJUNCTWEAS THE Moon or DESIRE, . 42 1. The Optative Subjunctive, . 42 2. Sentences of Purpose, . L . .- . ‘ . 43 a.P11re Final Sentences, ' . ._ . 43 6. Verbs of Fearing, . '47 i o. The Complementary Final Sentence, . .' . ,1 47 3. Sentences of Result, ' . 54 Subjunctive 111 a. Relative Clause with Negative Antece— dent, . - . 55 Life, .‘ . .57 THE SUBJUNCTIVE MOOD IN THE OLD ENGLISH VERSION OF BEDE’S ECCLESIASTICAL HISTORY A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE ACADEMIC FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA FOR THE DEGREE. -

The Origin of the Greek Pluperfect

Princeton/Stanford Working Papers in Classics The Origin of the Greek Pluperfect Version 1.0 July 2007 Joshua T. Katz Princeton University Abstract: The origin of the pluperfect is the biggest remaining hole in our understanding of the Ancient Greek verbal system. This paper provides a novel unitary account of all four morphological types— alphathematic, athematic, thematic, and the anomalous Homeric form 3sg. ᾔδη (ēídē) ‘knew’—beginning with a “Jasanoff-type” reconstruction in Proto-Indo-European, an “imperfect of the perfect.” © Joshua T. Katz. [email protected] 2 The following paper has had a long history (see the first footnote). This version, which was composed as such in the first half of 2006, will be appearing in more or less the present form in volume 46 of the Viennese journal Die Sprache. It is dedicated with affection and respect to the great Indo-Europeanist Jay Jasanoff, who turned 65 in June 2007. *** for Jay Jasanoff on his 65th birthday The Oxford English Dictionary defines the rather sad word has-been as “One that has been but is no longer: a person or thing whose career or efficiency belongs to the past, or whose best days are over.” In view of my subject, I may perhaps be allowed to speculate on the meaning of the putative noun *had-been (as in, He’s not just a has-been; he’s a had-been!), surely an even sadder concept, did it but exist. When I first became interested in the Indo- European verb, thanks to Jay Jasanoff’s brilliant teaching, mentoring, and scholarship, the study of pluperfects was not only not a “had-been,” it was almost a blank slate.