AZERBAIJAN in the WORLD ADA Biweekly Newsletter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Armenophobia in Azerbaijan

Հարգելի՛ ընթերցող, Արցախի Երիտասարդ Գիտնականների և Մասնագետների Միավորման (ԱԵԳՄՄ) նախագիծ հանդիսացող Արցախի Էլեկտրոնային Գրադարանի կայքում տեղադրվում են Արցախի վերաբերյալ գիտավերլուծական, ճանաչողական և գեղարվեստական նյութեր` հայերեն, ռուսերեն և անգլերեն լեզուներով: Նյութերը կարող եք ներբեռնել ԱՆՎՃԱՐ: Էլեկտրոնային գրադարանի նյութերն այլ կայքերում տեղադրելու համար պետք է ստանալ ԱԵԳՄՄ-ի թույլտվությունը և նշել անհրաժեշտ տվյալները: Շնորհակալություն ենք հայտնում բոլոր հեղինակներին և հրատարակիչներին` աշխատանքների էլեկտրոնային տարբերակները կայքում տեղադրելու թույլտվության համար: Уважаемый читатель! На сайте Электронной библиотеки Арцаха, являющейся проектом Объединения Молодых Учёных и Специалистов Арцаха (ОМУСA), размещаются научно-аналитические, познавательные и художественные материалы об Арцахе на армянском, русском и английском языках. Материалы можете скачать БЕСПЛАТНО. Для того, чтобы размещать любой материал Электронной библиотеки на другом сайте, вы должны сначала получить разрешение ОМУСА и указать необходимые данные. Мы благодарим всех авторов и издателей за разрешение размещать электронные версии своих работ на этом сайте. Dear reader, The Union of Young Scientists and Specialists of Artsakh (UYSSA) presents its project - Artsakh E-Library website, where you can find and download for FREE scientific and research, cognitive and literary materials on Artsakh in Armenian, Russian and English languages. If re-using any material from our site you have first to get the UYSSA approval and specify the required data. We thank all the authors -

Spotlight on Azerbaijan

Spotlight on azerbaijan provides an in-depth but accessible analysis of the major challenges Azerbaijan faces regarding democratic development, rule of law, media freedom, property rights and a number of other key governance and human rights issues while examining the impact of its international relationships, the economy and the unresolved nagorno-Karabakh conflict on the domestic situation. it argues that UK, EU and Western engagement in Azerbaijan needs to go beyond energy diplomacy but that increased engagement must be matched by stronger pressure for reform. Edited by Adam hug (Foreign policy Centre) Spotlight on Azerbaijan contains contributions from leading Azerbaijan experts including: Vugar Bayramov (Centre for Economic and Social Development), Michelle Brady (American Bar Association Rule of law initiative), giorgi gogia (human Rights Watch), Vugar gojayev (human Rights house-Azerbaijan) , Jacqueline hale (oSi-EU), Rashid hajili (Media Rights institute), tabib huseynov, Monica Martinez (oSCE), Dr Katy pearce (University of Washington), Firdevs Robinson (FpC) and Denis Sammut (linKS). The Foreign Policy Centre Spotlight on Suite 11, Second floor 23-28 Penn Street London N1 5DL United Kingdom www.fpc.org.uk [email protected] aZERBaIJaN © Foreign Policy Centre 2011 Edited by adam Hug all rights reserved ISBN-13 978-1-905833-24-5 ISBN-10 1-905833-24-5 £4.95 Spotlight on Azerbaijan Edited by Adam Hug First published in May 2012 by The Foreign Policy Centre Suite 11, Second Floor, 23-28 Penn Street London N1 5DL www.fpc.org.uk [email protected] © Foreign Policy Centre 2012 All Rights Reserved ISBN 13: 978-1-905833-24-5 ISBN 10: 1-905833-24-5 Disclaimer: The views expressed in this report are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Foreign Policy Centre. -

The U.S. South Caucasus Strategy and Azerbaijan

THE U.S. SOUTH CAUCASUS STRATEGY AND AZERBAIJAN This article analyzes the evolution of U.S. foreign policy in the South Cauca- sus through three concepts, “soft power”, “hard power” and “smart power” which have been developed under the administrations of Bill Clinton, George W. Bush and Barack Obama respectively. The authors also aim to identify how the US strategy towards this region has been perceived in Azerbaijan, which, due to its geographical position, energy resources and geopolitical environment, is one of the “geopolitical pivots of Eurasia”. Inessa Baban & Zaur Shiriyev* * Inessa Baban is a Ph.D candidate in geopolitics at Paris-Sorbonne University of France. She is a former visiting scholar at Center for Strategic Studies under the President of Azerbaijan. Zaur Shiriyev is a foreign policy analyst at the same think tank. The views expressed in this article are entirely personal. 93 VOLUME 9 NUMBER 2 INESSA BABAN & ZAUR SHIRIYEV he U.S. strategy towards the South Caucasus has become one of the most controversial issues of American foreign policy under the Obama administration. Most American experts argue that because of the current priorities of the U.S. government, the South Caucasus region does not get the attention that it merits. Even if they admit that none of U.S.’ interests in the Caucasus “fall under the vital category”1 there is a realization that Washington must reconsider its policy towards this region which matters geopolitically, economically and strategically. The South Caucasus, also referred as Transcaucasia, is located between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, neighboring Central Asia to the east, the Middle East to the south, and Eastern Europe to the west, hence connecting Europe to Asia. -

I Am Delighted to Welcome You to the Pages of Azerbaijan in the World, the New Biweekly of the Azerbaijan Diplomatic Academy

AZERBAIJAN IN THE WORLD ADA Biweekly Newsletter Vol. 1, No. 1 February 1, 2008 [email protected] In this issue: -- Greetings from the Foreign Minister -- Greetings from the Rector -- Paul Goble, “Azerbaijan on the Cusp” -- Sevinge Yusifzade, “A Not So Distant Model” -- Murad Ismayilov, “Azerbaijani National Identity and Baku’s Foreign Policy” -- A Chronology of Azerbaijan’s Foreign Policy -- Note to Readers Greetings from H.E. Elmar Mammadyarov Minister of Foreign Affairs Republic of Azerbaijan I am delighted to welcome you to the pages of Azerbaijan in the World, the new biweekly of the Azerbaijan Diplomatic Academy. Given its booming economy, increasing presence in international affairs and growing prestige, Azerbaijan today deserves your attention, and I am confident that this new electronic publication will serve as a useful guide to its foreign policy. Situated in one of the most geopolitically sensitive regions in the world, my country affects and is affected by various regional trends, energy issues, and security threats, and in order to understand where Baku is heading, you will want to keep track of developments in all these areas. And Azerbaijan in the World will thus feature articles on those issues as well. Because Ambassador Pashayev, the rector of the Azerbaijan Diplomatic Academy, and Paul Goble, ADA’s director of research and publications, stand behind this project, I have every confidence in its success. I plan to be an attentive reader as well as a frequent contributor and very much hope you will be both as well. Greetings from Ambassador Hafiz Pashayev Rector Azerbaijan Diplomatic Academy As the rector of the Azerbaijan Diplomatic Academy, I want to echo the words of Foreign Minister Elmar Mammadyarov about our new biweekly, “Azerbaijan in the World” and take this opportunity to tell you something about our institution, its activities, and its goals. -

Senate Foreign Relations Committee

SENATE OF PAKISTAN PAKISTAN WORLDVIEW Report - 21 SENATE FOREIGN RELATIONS COMMITTEE Visit to Azerbaijan December, 2008 http://www.foreignaffairscommittee.org List of Contents 1. From the Chairman’s Desk 5 2. Executive Summary 9-14 3. Members of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee Delegation to Azerbaijan 17 4. Verbatim record of the meetings held in Azerbaijan: Meeting with Pakistan-Azerbaijan Friendship Group 21-24 Meeting with Permanent Commission of the Milli Mejlis for International and Inter-Parliamentary Relations 25-26 Meeting with Permanent Commission of the Milli Mejlis for Social Affairs 27 Meeting with Permanent Commission of the Milli Mejlis for Security and Defence 28-29 Meeting with Chairman of the Milli Mejlis (National Assembly) 30-34 Meeting with Vice Chairman of New Azerbaijan Party 35-37 Meeting with Minister for Industry and Energy 38-40 Meeting with President of the Republic of Azerbaijan 41-44 Meeting with the Foreign Minister 45-47 Meeting with the Prime Minister of Azerbaijan 48-50 5. Appendix: Pakistan - Azerbaijan Relations 53-61 Photo Gallery of the Senate Foreing Relations Committee Visit to Azerbaijan 65-66 6. Profiles: Profiles of the Chairman and Members of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee 69-76 Profiles of the Committee Officials 79-80 03 Visit to Azerbaijan From the Chairman’s Desk The Report on Senate Foreign Relations Committee visit to Azerbaijan is of special significance. Azerbaijan emerged as an independent country in 1991 with the breakup of Soviet Union, along with five other Central Asian states. Pakistan recognized it shortly after its independence and opened diplomatic relations with resident ambassadors in the two capitals. -

India-Azerbaijan Bilateral Relations India and Azerbaijan Have Close

India-Azerbaijan Bilateral Relations India and Azerbaijan have close friendly relations and growing bilateral cooperation based on old historical relations and shared traditions. The Ateshgah fire temple in the vicinity of Baku is a fine example. This medieval monument with Devanagri and Gurmukhi wall inscriptions is a symbol of the age-old relationship between the two countries when Indian merchants heading towards Europe through the Great Silk Route used to visit Azerbaijan. In the recent past, President Dr. S. Radhakrishnan, Prime Minister Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru and film star Raj Kapoor had visited Baku. Famous Azerbaijani artist Rashid Behbudov, a close friend of Raj Kapoor promoted Azeri music in India and Indian music in Azerbaijan. Famous singer Elmira Rahimova spent two years studying Indian music/dance in India in the late 1950s. Diplomatic relations: India recognized Azerbaijan in December 1991. Diplomatic relations with Azerbaijan were established on 28th February, 1992. An Indian resident mission was opened in Baku in March 1999. Azerbaijan opened its first resident mission in New Delhi in October, 2004. The leadership of India and Azerbaijan are keen to form a reliable, strong, vibrant and mutually beneficial partnership with each-other. Bilateral agreements: An agreement on Economic and Technical Cooperation was signed in June, 1998. An Agreement to establish the India-Azerbaijan Intergovernmental Commission (IGC) on Trade, Economic, Scientific and Technological Cooperation was signed in April 2007. Air Service Agreement and a Protocol of Intergovernmental Commission were signed in April 2012. Agreements on Mutual Legal Assistance Treaty (MLAT) in Civil & Commercial Matters and Mutual Legal Assistance Treaty in Criminal Matters and Extradition Treaty were signed in April 2013. -

Combatting and Preventing Corruption in Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia How Anti-Corruption Measures Can Promote Democracy and the Rule of Law

Combatting and preventing corruption in Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia How anti-corruption measures can promote democracy and the rule of law Combatting and preventing corruption in Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia How anti-corruption measures can promote democracy and the rule of law Silvia Stöber Combatting and preventing corruption in Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia 4 Contents Contents 1. Instead of a preface: Why (read) this study? 9 2. Introduction 11 2.1 Methodology 11 2.2 Corruption 11 2.2.1 Consequences of corruption 12 2.2.2 Forms of corruption 13 2.3 Combatting corruption 13 2.4 References 14 3. Executive Summaries 15 3.1 Armenia – A promising change of power 15 3.2 Azerbaijan – Retaining power and preventing petty corruption 16 3.3 Georgia – An anti-corruption role model with dents 18 4. Armenia 22 4.1 Introduction to the current situation 22 4.2 Historical background 24 4.2.1 Consolidation of the oligarchic system 25 4.2.2 Lack of trust in the government 25 4.3 The Pashinyan government’s anti-corruption measures 27 4.3.1 Background conditions 27 4.3.2 Measures to combat grand corruption 28 4.3.3 Judiciary 30 4.3.4 Monopoly structures in the economy 31 4.4 Petty corruption 33 4.4.1 Higher education 33 4.4.2 Health-care sector 34 4.4.3 Law enforcement 35 4.5 International implications 36 4.5.1 Organized crime and money laundering 36 4.5.2 Migration and asylum 36 4.6 References 37 5 Combatting and preventing corruption in Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia 5. -

Baku Dialoguesbaku Dialogues Policy Perspectives on the Silk Road Region

BAKU DIALOGUESBAKU DIALOGUES POLICY PERSPECTIVES ON THE SILK ROAD REGION Vol. 4 | No. 1 | Fall 2020 Silk Road Region as Global Keystone? Geopolitics & Connectivity in the Heart of the World Between Eurasia and the Middle East Geopolitical Keystone Svante Cornell Nikolas K. Gvosdev Against ‘the Blob’ Not A Top European Priority Michael A. Reynolds Amanda Paul Five-Star Hubs Eurasia, the Hegemon, and the Three Sovereigns Taleh Ziyadov Pepe Escobar Silk Road Pathways Completing the Southern Gas Corridor Yu Hongjun Akhmed Gumbatov Taking Stock of Regional Quandaries The Karabakh Peace Process Dennis Sammut Iran’s Longstanding Cooperation with Armenia Brenda Shaffer The OSCE and Minorities in the Silk Road Region Lamberto Zannier Profile in Leadership Zbigniew Brzezinski: My Friendship with America’s Geopolitical Sage Hafiz Pashayev Baku Dialogues Interview Strategic Equilibrium: Azerbaijan’s Foreign Policy Hikmat Hajiyev 1 Vol. 4 | No. 1 | Fall 2020 ISSN Print: 2709-1848 ISSN Online: 2709-1856 BAKU DIALOGUES BAKU DIALOGUESBAKU DIALOGUES POLICY PERSPECTIVES ON THE SILK ROAD REGION Vol. 4 | No. 1 | Fall 2020 Silk Road Region as Global Keystone? Geopolitics & Connectivity in the Heart of the World Between Eurasia and the Middle East Geopolitical Keystone Svante Cornell Nikolas K. Gvosdev Against ‘the Blob’ Not A Top European Priority Michael A. Reynolds Amanda Paul Five-Star Hubs Eurasia, the Hegemon, and the Three Sovereigns Taleh Ziyadov Pepe Escobar Silk Road Pathways Completing the Southern Gas Corridor Yu Hongjun Akhmed Gumbatov Taking Stock of Regional Quandaries The Karabakh Peace Process Dennis Sammut Iran’s Longstanding Cooperation with Armenia Brenda Shaffer The OSCE and Minorities in the Silk Road Region Lamberto Zannier Profile in Leadership Zbigniew Brzezinski: My Friendship with America’s Geopolitical Sage Hafiz Pashayev Baku Dialogues Interview Strategic Equilibrium: Azerbaijan’s Foreign Policy Hikmat Hajiyev Vol. -

Azerbaijan0913 Forupload 1.Pdf

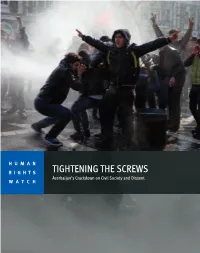

HUMAN RIGHTS TIGHTENING THE SCREWS Azerbaijan’s Crackdown on Civil Society and Dissent WATCH Tightening the Screws Azerbaijan’s Crackdown on Civil Society and Dissent Copyright © 2013 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-0473 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. We investigate and expose human rights violations and hold abusers accountable. We challenge governments and those who hold power to end abusive practices and respect international human rights law. We enlist the public and the international community to support the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org SEPTEMBER 2013 978-1-62313-0473 Tightening the Screws Azerbaijan’s Crackdown on Civil Society and Dissent Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Arrest and Imprisonment ......................................................................................................... -

Ahmet Davutoglu: I`M Proud of Azerbaijan`S Rapid Development That I See Each Time I Visit the Country

26 SEPTEMBER 2014 THE EMBASSY OF THE REPUBLIC OF AZERBAIJAN TO THE COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Israeli Ambassador: Tolerance in Azerbaijan is an UN General example to the President Ceremony of the received the UK Assembly discussed entire world Southern Gas the situation in the Minister of STI Corridor occupied territories Page 3 Page 2 Page 2 Page 2 PRESS RELEASE Ahmet Davutoglu: I`m proud of Azerbaijan`s rapid development that I see each time I visit the country 19.09.2014 Turkish Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoglu has hailed Azerbaijan`s development as he met chairman of the country`s parliament Ogtay Asadov. “I`m proud of Azerbaijan`s rapid development that I see each time I visit the country,” said the Turkish Premier, who is on an official visit to Baku. “Only two issues have remained unchanged amid the crises of recent years. First, Azerbaijani- Turkish friendship and brotherhood has remained unchanged. Second, there has been no delay in the development of either Azerbaijan or Turkey. Our “Settlement of the problem, countries are developing at a rapid place.” restoration of brotherly Mr. Davutoglu said that as the prime minister he paid his Azerbaijan`s territorial integrity is first visit to Azerbaijan, adding he had spared no efforts to important to Turkey as much as it serve the people of Turkey and Azerbaijan regardless of his is important to Azerbaijan.” post. He touched upon the Armenia-Azerbaijan Nagorno- Karabakh conflict, saying Turkey “has always backed Azerbaijan`s just stance”. “Settlement of the problem, restoration of brotherly Azerbaijan`s territorial integrity is important to Turkey as much as it is important to Azerbaijan.” Mr. -

Echo of Khojaly Tragedy

CHAPTER 3 ECHO OF KHOJALY Administrative Department of the President of the Republic of Azerbaijan P R E S I D E N T I A L L I B R A R Y ─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────── CONTENTS Kommersant (Moscow) (February 27, 2002) ..................................................................................... 15 15 th year of Khojaly genocide commemorated (February 26, 2007) ................................................ 16 Azerbaijani delegation to highlight Nagorno-Karabakh issue at OSCE PA winter session (February 3, 2008) ............................................................................................................................................... 17 On this night they had no right even to live (February 14, 2008) ...................................................... 18 The horror of the night. I witnessed the genocide (February 14-19, 2008) ....................................... 21 Turkey`s NGOs appeal to GNAT to recognize khojaly tragedy as genocide (February 13, 2008) ... 22 Azerbaijani ambassador meets chairman of Indonesian Parliament’s House of Representatives (February 15, 2008) ............................................................................................................................ 23 Anniversary of Khojaly genocide marked at Indonesian Institute of Sciences (February 18, 2008). 24 Round table on Khojaly genocide held in Knesset (February 20, 2008) ........................................... 25 Their only «fault» was being Azerbaijanis (February -

A Comparative Foreign Policy Analysis of Weak States: the Case of the Caucasus States Yasar Sari Charlottesville, Virginia B.A

A Comparative Foreign Policy Analysis of Weak States: The Case of the Caucasus States Yasar Sari Charlottesville, Virginia B.A., Istanbul University, 1993 M.A., Old Dominion University, 1997 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The Woodrow Wilson Department of Politics University of Virginia December 2008 Abstract Keywords: Caucasus states, Russia, foreign policy analysis, weak state The key features of foreign policy formulation and execution in Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia are selected in an attempt to reveal the sources of foreign policy-behavior of new, post- Soviet (and in effect post-imperial) states during the 1990s. More specifically, this is a comparative study of the foreign policies of the Caucasus states as new states toward the Russian Federation as the ex-imperial center. The purpose of the dissertation is to verify the relative significance of internal factors and level of external assistance in shaping the foreign policy of weak states. Therefore, the key theoretical contribution of the dissertation is to understand foreign policy change in weak states during their early years of independence. The newly independent Caucasus states are weak states. The most urgent problems facing these newly independent states following their independence were domestic ones. The time period covered is between 1991 and 1999, which in turn is divided into two sub-periods: 1991- 1995, the period of confusion and 1995 to 1999, the period of consolidation. This dissertation centers upon the explanation of two factors: the level of domestic strain of weak states and their relations to the external world.